1. Guesstimating Typical Living Standards in the Agrarian Age

For Econ 210a S 2024; time to apply all the lessons I have learned in the past decade to rejiggering how "Introduction to Economic History for Graduate Students" works; the key question is: how...

For Econ 210a S 2024; time to apply all the lessons I have learned in the past decade to rejiggering how "Introduction to Economic History for Graduate Students" works; the key questions are: how much time to spend on each topic? and which topics belong on day 1, when reading will have been hit-or-miss?

REQUIRED READINGS:

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2023. “Ensorcelled by the Devil of Malthus.” Brad DeLong’s Grasping Reality <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/ensorcelled-by-e-devil-of-malthus>.

Steckel, Richard H. 2008. “Biological Measures of the Standard of Living.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22 (1): 129–52 <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.22.1.129>

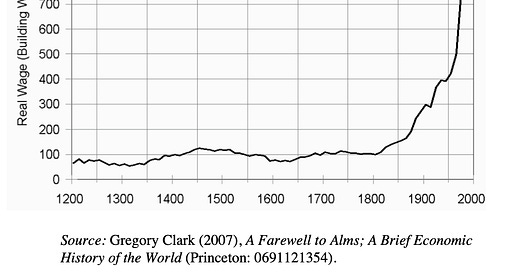

Clark, Gregory. 2004. “The Condition of the Working Class in England, 1209–2004.” Journal of Political Economy 113 (6): 1307–34 <https://faculty.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/gclark/papers/Working%20Class.pdf>

FOR REFERENCE:

Lee, Ronald. 2003. “The Demographic Transition: Three Centuries of Fundamental Change.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 17 (4): 167–190 <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/089533003772034943>.

Livi-Bacci, Massimo. 2017. A Concise History of World Population. 6th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell <https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof0000livi_d6o3>

INTRODUCTION: Guesstimating Typical Living Standards in the Agrarian Age:

What can we say about typical labor productivity levels, and thus typical human living standards, over the past, say, 10,000 years?

For years since 1800 we actually have official and semi-official economic statistics—although with all the problems of interpreting them and correcting them for biases outlined by William Nordhaus (1997). Before 1800 our information is much more scattered. But I think that it is, in the end, equally compelling. We have at least the broad features of labor productivity, and thus of typical living standards, nailed down.

Start with the fact the we have the long-run demography at least guesstimated.

Global human populations grew from perhaps 5 million at the time of the Neolithic Revolution—the discovery of settled agriculture and animal husbandry—some ten thousand years ago, to perhaps 200 million in year 150 (an annual rate of population growth of 0.04% per year). It then roughly tripled between the year 150 and 1500 (an annual rate of population growth of 0.07% per year). Population grew by perhaps fifty percent in the commercial-imperial age to 1770 (an annual rate of population growth of 0.14% per year); nearly doubled over the next century to 1870 (a rate of growth of 0.65% per year); and since 1870 has more than sextupled, growing to our current population of roughly 8.4 billion (an annual rate of population growth of 1.3% per year).

That we know what a nutritionally, unstressed pre-artificial birth control population does under conditions of patriarchy. It doubles every 50 years. Sometimes it grows faster. 1.4% per year. Or more. But in the long agrarian age from -8000 to 1500 the rate of population growth was only 1/140 of that. And in the 1500 to 1770 commercial-imperial age it was only 1/10. And even in the 1770 to 1870 British industrial-revolution century it was less than half.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.