FIRST: Michael Hiltzik Interview on “Slouching Towards Utopia”

Very nicely done by Michael:

Michael Hiltzik: Column: How did America get addicted to a policy that fails everyone but the rich?: ‘Social Democratic policies crafted in the 1930s succeeded in creating a long era of widespread prosperity, then suddenly lost their credibility in the mid-1970s. They were replaced by the neoliberalism of Ronald Reagan, which failed to help anyone but the rich, yet still governs American economic policy. The ascent of neoliberalism and its staying power “is a puzzle,” J. Bradford DeLong writes in his magisterial new economic history of the 20th century, Slouching Towards Utopia <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>. It’s the central puzzle that DeLong, a professor of economics at UC Berkeley, a widely followed economics blogger and one of our leading critics of economic inequality, aims to examine…

A few of Michael’s passages that made me think, and a few comments on the:

By bringing to the middle class and working class the recognition of their shared interest in a more inclusive economy, the [Great] Depression produced a drive for social insurance and social justice. Franklin D. Roosevelt… the era of social democracy, reflecting the views of Hungarian economist Karl Polanyi…. “Polanyi’s counter was that whether saying the market can do it all or that it’s all we can have, people will not stand for it,” DeLong told me during a lengthy conversation about his book. “You will get a large group of people wanting to elect someone who will do something about the system.” In the post-Depression era, it became understood that “not only shouldn’t the market be left to do it all,” DeLong says, “it can’t do it all or very much unless it is properly primed and aided and guided”…

Andrew, Carnegie and company had claimed that the market and allocation of wealth was "just" in at least three senses: (1) it rewarded the virtues of diligence and talent; (2) it was progressive for the race in a social-darwinist mode; and (3) it was a fair contest, in that differences in “starting positions” were either small or were fairly bought as part of the reward your ancestors deserved for their diligence and talent. Von Hayek’s declarations that the market allocation was unfair but that we dared not monkey with it—that was at least more clear-sighted.

Andrew Carnegie and company had great sway. Here is George Orwell, from The Road to Wigan Pier, writing in the mid-1930s:

I first became aware of the unemployment problem in 1928…. When I first saw unemployed men at close quarters, the thing that horrified and amazed me was to find that many of them were ashamed of being unemployed. I was very ignorant, but not so ignorant as to imagine that when the loss of foreign markets pushes two million men out of work, those two million are any more to blame than the people who draw blanks in the Calcutta Sweep.

But at that time nobody cared to admit that unemployment was inevitable, because this meant admitting that it would probably continue. The middle classes were still talking about 'lazy idle loafers on the dole' and saying that 'these men could all find work if they wanted to', and naturally these opinions percolated to the working class themselves. I remember the shock of astonishment it gave me, when I first mingled with tramps and beggars, to find that a fair proportion, perhaps a quarter, of these beings whom I had been taught to regard as cynical parasites, were decent young miners and cotton-workers gazing at their destiny with the same sort of dumb amazement as an animal in a trap.

They simply could not understand what was happening to them. They had been brought up to work, and behold! it seemed as if they were never going to have the chance of working again. In their circumstances it was inevitable, at first, that they should be haunted by a feeling of personal degradation. That was the attitude towards unemployment in those days: it was a disaster which happened to you as an individual and for which you were to blame.

When a quarter of a million miners are unemployed, it is part of the order of things that Alf Smith, a miner living in the back streets of Newcastle, should be out of work. Alf Smith is merely one of the quarter million, a statistical unit. But no human being finds it easy to regard himself as a statistical unit. So long as Bert Jones across the street is still at work, Alf Smith is bound to feel himself dishonoured and a failure. Hence that frightful feeling of impotence and despair which is almost the worst evil of unemployment—far worse than any hardship, worse than the demoralization of enforced idleness, and Only less bad than the physical degeneracy of Alf Smith's children, born on the P.A.C.

The Great Depression broke this Carnegie-style pattern of thought for nearly two generations. Yet somehow by the late 1970s it was back, with the claim that the market rewarded diligence and talent, so that while the rich were lucky, the poor were not unlucky but merely undiligent and untalented:

It all came apart. It would have been hard to sustain annual growth of 3% under any circumstances, but the 1970s brought the oil shocks, which tripled the price of oil, produced high inflation and provoked a sharp economic slowdown. Opinion soured on redistribution of income to sustain the poor, and on environmental regulations. “The fading memory of the Great Depression,” DeLong writes, “led to the fading of the middle class’s belief ... that they, as well as the working class, needed social insurance.” The stage was set for what DeLong calls “the neoliberal turn”…. One insight that DeLong’s approach leads us to is how little the right’s attack on social justice initiatives has evolved in nearly a half-century. In 1980, conservative economist Martin Feldstein inveighed against unemployment insurance because it would produce inflation, health and safety regulations because they would reduce productivity, and welfare because it would “weaken family structures,” Medicare and Medicaid because they would drive up healthcare costs. Even earlier, in 1962, Nobel economics laureate George Stigler lamented the “insolence” of civil rights demonstrators. Complaints about the “permissiveness” of liberal parents was a feature of Republican critiques. Compare that to today’s GOP shibboleths…

It would have been possible for Marty to take a position on this, that I would have a greed with: that the economy needs "hard incentives", but those hard incentives must be coupled with "setting people up for success". Governance as as a principal task to set things up, so that nobody (or very few) are put in situations in which they are required to accomplish tasks impossible for them. This was what I call Jack Kemp right-neoliberalism. But there were never more than a very few Jack Kemp right-neoliberals. And now I think there are none.

“Resurrecting social democracy is not in the cards, because it rested on technologies of production and social organization as they existed in the 1950s. Nor is resurrecting Reaganism… “

This, I think, is an absolutely key point. Friedrich Engels thought that society had to accomodate itself to the changing underlying forces of production: that you could not have a gunpowder-empire in the feudal age without gunpowder, and that you could not have a gunpowder-empire in the steampower age, but that gunpowder-empires did fine in the age of the caravel and the windmill. The problem with Engels was that he thought that the steampower age was the acme. He did not look forward, after 1000 years in which you had two (or maybe one and a half?) transitions of mode-of-production from feudalism to commercial to steam-industrial, that post-1870 we would go from steampower to second-industrialization to mass-production to mass-consumption to global-value-chain to info-biotech. And no modes of social organization and relations of production can still be effective across any of these transitions.

“If there is no left-wing alternative to neoliberalism, the right-wing alternatives are much more unpleasant—a politics of ‘you have enemies and you need to give me close to plenary power so I can protect you.’ That’s a dangerous situation, and one that we seem to be drifting towards”. Whether the hands on America’s economic tiller are capable of guiding us to a fair future remains in question…

And this is the thing that makes me most pessimistic. The potential alternatives to neoliberalism that have energy outside of relatively small cadres seem to me to be very unpleasant indeed. We may well wind up wishing for the good old days of the Neoliberal Order.

Gee, I’m depressed this month, am I not?

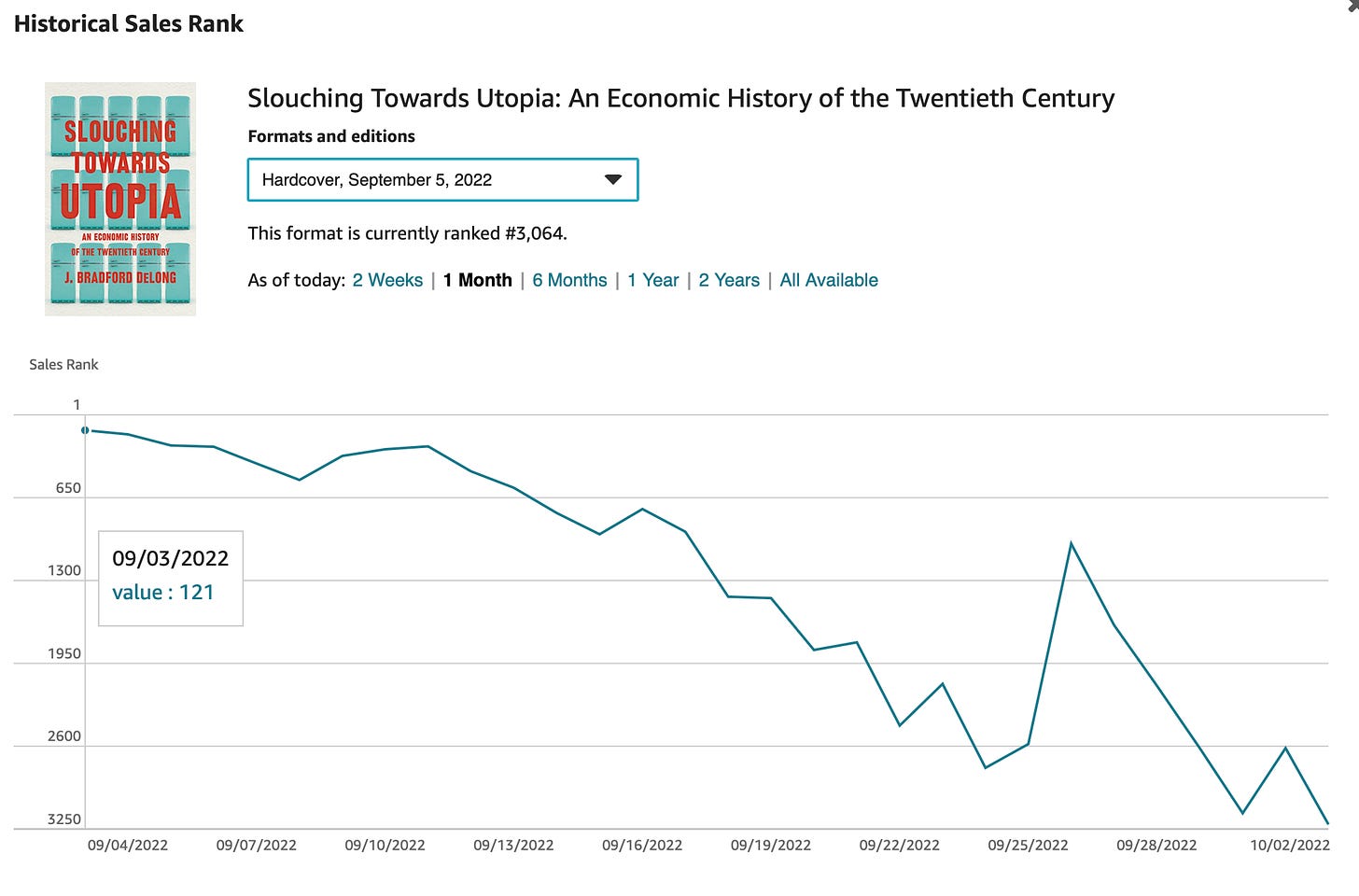

One Image: Amazon (Hardcover) Daily Sales Rank:

For Slouching Towards Utopia <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>:

From the weekly sales numbers, it looks as though sales are roughly proportional to 1/[sales rank] in the relevant range from [sales rank] = 100 to [sales rank] = 2500, with total sales of roughly 10,000 through the first two-thirds of September…

Must-Read: Musk vs. Twitter:

Chancery Daily: Twitter v. Musk Spotlight 🔦: ‘What does [the Musk Parties'] letter actually say or attempt to do?... It offers to close the deal on the terms that Musk promised to close the deal back in April, which promise he has subsequently spent months and millions trying to revoke. But… for real this time? The entirely credulous response from the media and most onlookers likely has some (perhaps unwitting) foundation in reality. The letter doesn’t say much, it doesn’t do much, but it does mean something. It means that Elon’s mindset has changed.... Doing the deal has been the nearly inevitable endgame of this whole charade for the past several months. On its face, his claim is weak and has little known support in fact or law. So, the deal was going to get done. When it gets done by his acquiescence instead of the Court’s insistence, most likely people will celebrate that the reporting today was all accurate! See, the deal did get done! But, to me, that’s not the point. The way it’s being reported is as though the deal is now done, and I assure you, with what we currently know, it is not.... To me, it feels like death by a thousand cuts, not one motivating event. If he is really motivated, he will do a lot more than send a mealy-mouthed letter via overnight courier. He will put his money where his mouth is, and he will come to the table to close. ‘Twill be quite interesting to see what tomorrow brings...

Other Things That Went Whizzing by…

Very Briefly Noted:

Dave Lee: The ever-expanding job of preserving the internet’s backpages: ‘A quarter of a century after it began collecting web pages, the Internet Archive is adapting to new challenges…

David Smith: ‘Testing an Apple Watch Ultra in the Scottish Highlands’

Michael Hiltzik: Column: How did America get addicted to a policy that fails everyone but the rich?

Frederik Gieschen: Thinking About the Next Warren Buffett”: ‘Munger: “Young lawyers frequently come to me and say, ‘How can I quit practicing law and become a billionaire instead?’… The next Warren Buffett, whoever they are, will not be afraid to ask the question that is on everyone’s mind. But they will also not be sitting in the audience waiting to be handed enlightenment…

Emily Holland: Permanent Rupture: The European-Russian Energy Relationship Has Ended with Nord Stream…

Kaushik Basu: All the King’s Games: ‘Do Russians want to oust Putin and restore democracy? If you ask people familiar with Russia, they will most likely say that most of the population still supports him. I have my doubts. Tyrants always appear to have more support than they do until they are gone, because feigning support is a survival strategy...

¶s:

John Ganz: The Matteotti Crisis: ‘Mussolini’s success was not guaranteed…. The King might have withdrawn his mandate, his parliamentary allies could have fled, the opposition might have adopted a more muscular strategy, or the Fascist ultras may have launched a coup that justified governmental suppression of the Fascists in response. Mussolini took advantage of the disorganization of his opponents and the craven opportunism of his allies. It was the sort of tactical victory he had become expert in, riding out the storms while just managing to keep his coalition together. The killing of Giacomo Matteotti may have been reckless in that it created an unstable situation and threatened his rule, but ultimately it proved to be “the right move:” Mussolini removed an opponent of extraordinary courage and moral authority and created the conditions for consolidating control…

Dan Davies: A non-random walk down Lombard Street: ‘Not all market interventions are bailouts and not all bailouts are bad…. The idea that financial crises can be managed by mitigating the consequences ex post rather than preventing the problem ex ante has a bad reputation, mainly as a result of Alan Greenspan’s use of it as an excuse for not doing more during the 2000s. But it’s not intrinsically unorthodox central banking. The optimal frequency of crises, as Professor Richard Portes once told me, is not zero. A central bank can’t anticipate everything and the perfect regulatory system doesn’t exist. Since central banks have the power to expand their balance sheets without limit, and so the ability to unstick frozen markets, why shouldn’t they use it sometimes? As long as people don’t get into the habit of expecting to be rescued simply from falling markets, this is a valid part of the toolkit…

Joe Nye: What Caused the Ukraine War?: ‘Distinguish between deep, intermediate, and immediate causes…. Putin lit the match… on February 24…. The intermediate cause was a refusal to see Ukraine as a legitimate state…. Putin wants to restore what he calls the “Russian world”…. [But] while NATO’s decision in 2008 may have been misguided, Putin’s change of attitude predated it…. Behind all this were the remote or deep causes that followed the end of the Cold War…

Two disparate notes:

1. There is a distinction between neoliberalism-in-theory and neoliberalism-in-practice. Neoliberalism-in-theory says: "Let the markets rip. We can make it up with taxation and redistribution." Neoliberalism-in-practice drops the second sentence. The distinction is that between economics and political economy. If market forces are too healthy, business influence over policy is too strong.

2. In response to Dan Davies: There is indeed an optimal positive rate of *firm* failures. The optimal rate of *systemic* failures is "zero." Which is why bank insolvency law is so important, and the failure to create a credible large bank insolvency regime is so deplorable.

"He will put his money where his mouth is, and he will come to the table to close."

I think what matters is how much money the Russians (presumably via an intermediary) put up.

"But there were never more than a very few Jack Kemp right-neoliberals. And now I think there are none."

2008-2009 killed my faith in good faith, so to speak. Nonetheless, the catechism is still muttered over the head of the decapitated bull as the incense wafts over the scene.

"We may well wind up wishing for the good old days of the Neoliberal Order. Gee, I’m depressed this month, am I not?"

As I recall you were sitting in front of your cereal with the spoon stuck in your mouth, contemplating therapy, back in 2009. It's worse from one perspective but better from another: at least it's out in the open so are at least not get steam-rollered.

elm

also russia's army has taken multiple soccer balls in the shorts