A Useful & Human Grand Narrative for the 21st Century

Sparked by my appearance on Ezra Klein's podcast...

What is a useful & human grand narrative for us to adopt for the remainder of the 21st century?

Let me start with Paul Seabright’s 2004 The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life <https://archive.org/details/companyofstrange0000seab>, and with two observations he makes.

The first observation is this: Recognize that if you drop any one of us in the wilderness alone, we die. We have to have allies, socii as the Romans called them. We have to be part of a society, of a group of humans with a division of labor in order to survive at all. And it has to be a large society with a sophisticated division of labor in order for any of us to prosper.

The second observation has to do with our engaging in gift-exchange relationships with others. We definitely give gifts. And we give gifts in reciprocal relationships. You definitely do not want to be that person who is always doing the work and contributing so that others can consume. But you also do not want to be that person who is always the moocher—that is tremendously psychologically disturbing. Adam Smith in his 1776 Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations called this the human

propensity to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another… common to all men, and to be found in no other race of animals…. Nobody ever saw a dog make a fair and deliberate exchange of one bone for another with another dog…

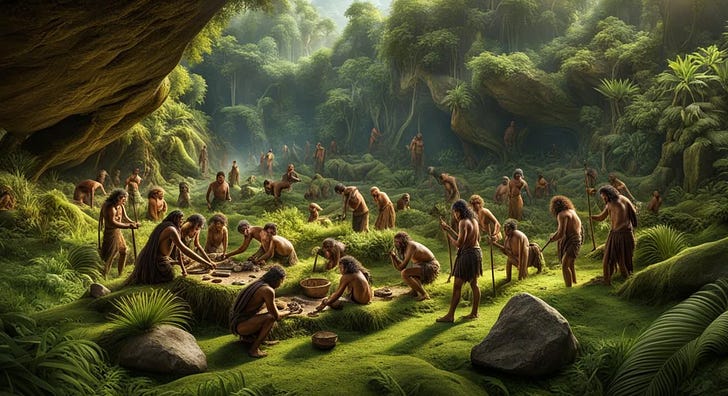

This human societal division of labor reaches very impressive heights very early—perhaps well before language as we now know it.

Witness Joseph Henrich’s book The Secret of Our Success recounting the capabilities of our late homo erectus ancestors:

Gesher Benot Ya'aqov… 750,000 years ago…. Hearths and areas for both stone-tool manufacturing and food processing… fire and… hand axes, cleavers, blades, knives, awls, scrapers, and choppers… [of] flint, basalt, and limestone, [with] tool manufacture… done on-site… from giant slabs carried in from a distant quarry… us[ing]… levers as part of the quarrying process. The basalt is of the highest quality and well quarried…. The inhabitants… obtained freshwater crabs, turtles, reptiles, and at least nine types of fish, including carp, sardines, and catfish…. There were seeds, acorns, olives, grapes, nuts, water chestnuts, and… the submerged prickly water lily…. Cumulative cultural evolution is up and running at this point, generating more know-how than you, me, or our lost European Explorers could have ginned up in a lifetime…

How did and how do we humans manage such a societal division of labor? It seems highly likely we did so on the back of these reciprocal gift-exchange relationships. but with whom can you enter into such relationships? Your kin. Your close friends. Your neighbors. With them, each person enters into this complicated dance of favors and obligations. It winds up, ideally, with everyone feeling benevolent and obligated—that they have received more than they have given, and so they ought to give more. And yet the entire mechanism has driven the creation of relationships in which everyone is getting massive amounts of surplus from not having to know everything and do everything by oneself.

However, this societal division of labor is limited: the links are between kin, friends, and neighbors. Overlapping social networks extend the potential for reach. The concepts of “friend” gets supercharged with the invention of kings and priests—the king is everyone’s “friend”, and everyone is the friend of Inanna and Dumuzi—which still further extends the reach of human gift-exchange relationships.

But the big change comes when we invent coinage. All of a sudden, you can have your gift-exchange relationship not just with your neighbors, your friends, your kin, your king, and your temple, but with everyone everywhere else in the world. All 8 billion plus of us can be part of a unified division of labor and a globe-spanning anthology intelligence.

We should realize how very lucky we are. How we all are close cousins. How we all are potentially involved in this reciprocal exchange of favors for one another.

And we need to take that very seriously.

There is another passage in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, one in which he uses human gift-exchange propensities as an intellectual judo move against mercantilists who say a low-wage economy is going to be a strong economy. In a low-wage economy, you see, you get a lot of work when you spend your gold. And that is a definite advantage, both in getting maximum military bang for your taxing power and in getting maximum élite purchasing power.

But Smith says: wait a minute. The society is made up of people. If most of the people are starving, that'd be a good society? And then comes the judo move:

It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged…

If you, member of the élite, create a society in which those whom you rely on find that your “gift-exchange” relationship with them has left them poorly fed, ill-clothed, and badly-lodged, then it is you who is the moocher.

Thus as we approach the remainder of the 21st century, it is the case, I think, that this is the most useful and human grand historical narrative we should adopt: We need to take seriously that the market economy is a gift-exchange network—although possibly only among honest people who trust each other, and who really do recognize that we are all very close cousins—and recognize that we all owe an enormous share of what prosperity we have to free gifts from people far away whom we do not know. And we should feel ourselves under a strong moral obligation to reciprocate—to pay it back, or pay forward.

There are people in Pakistan who wove the carpets that are on the floor of my living room.

They are beautiful. They are comfortable. They are warm on our feet in the winter.

I do not know these people. I have never met them. I have never even seen a picture of them.

But every time I walk on the carpets they made, I should think: I have these wonderful carpets. The dogs enjoy them even more than we do. And, when the dogs barf on them, we go to considerable effort to clean them up, because they are things of beauty and utility.

I really should recognize my obligation to the people back in Pakistan are who chose these colors and who tied these knots. Whatever I can do to make their lives better, I should do.

And I should always take care that their concerns are close to the front of my mind.

Henrich, Joseph. 2016. The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton: Princeton University Press. <https://archive.org/details/henrichthesecretofoursuccess.howcultureisdrivinghumanevolution>

Seabright, Paul. 2004. The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. <https://archive.org/details/companyofstrange0000seab>.

Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell. <https://archive.org/details/WealthOfNationsAdamSmith>

I guess it's worth noting, too, that the more complex the economy gets, it's harder to know who the moochers are. DEI officers? Receivers of carried interest taxed as capital gains income?

One of the great mysteries of the modern age is how conservatives are constantly terrified that at any moment the mob (manipulated by, although despised by, the "elites") will take over a vote themselves "free stuff."