A Woman Called "Toad": Mnesarete of Thespiai in Context: A Mode of Constrained Social Power in Classical Athens

Another thing I will have no time to teach in the fall. Kinda-sorta a review of Melissa Funke (2024). "Phryne: A Life in Fragments". London: Bloomsbury Academic...

Another thing I will have no time to teach in the fall. Kinda-sorta a review of Melissa Funke (2024). Phryne: A Life in Fragments. London: Bloomsbury Academic. <https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/phryne-9781350371873/>. Behind the paywall because I am unhappy with it, but really do not have any more time I can possibly afford to spend on it…

Well now, washed up just last week on some virtual island of Kythera as I was ambling on the virtual beach, a book I have very much wanted to read for years, but a book that I did not know that I wanted to read, and in fact a book that did not exist until February:

Though I must say if I were running the U.C. Berkeley Library I would invert the order of the categories: rather than “Nudity, Classical literature, Sex work, Prostitution, Women”, I would say “Women, Classical literature, Nudity, Sex work, Prostitution”.

Funke, Melissa. 2024. Phryne: A Life in Fragments. London: Bloomsbury Academic. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/phryne-9781350371873/.

Why have I wanted this book desperately, without knowing that I wanted it?

Back up.

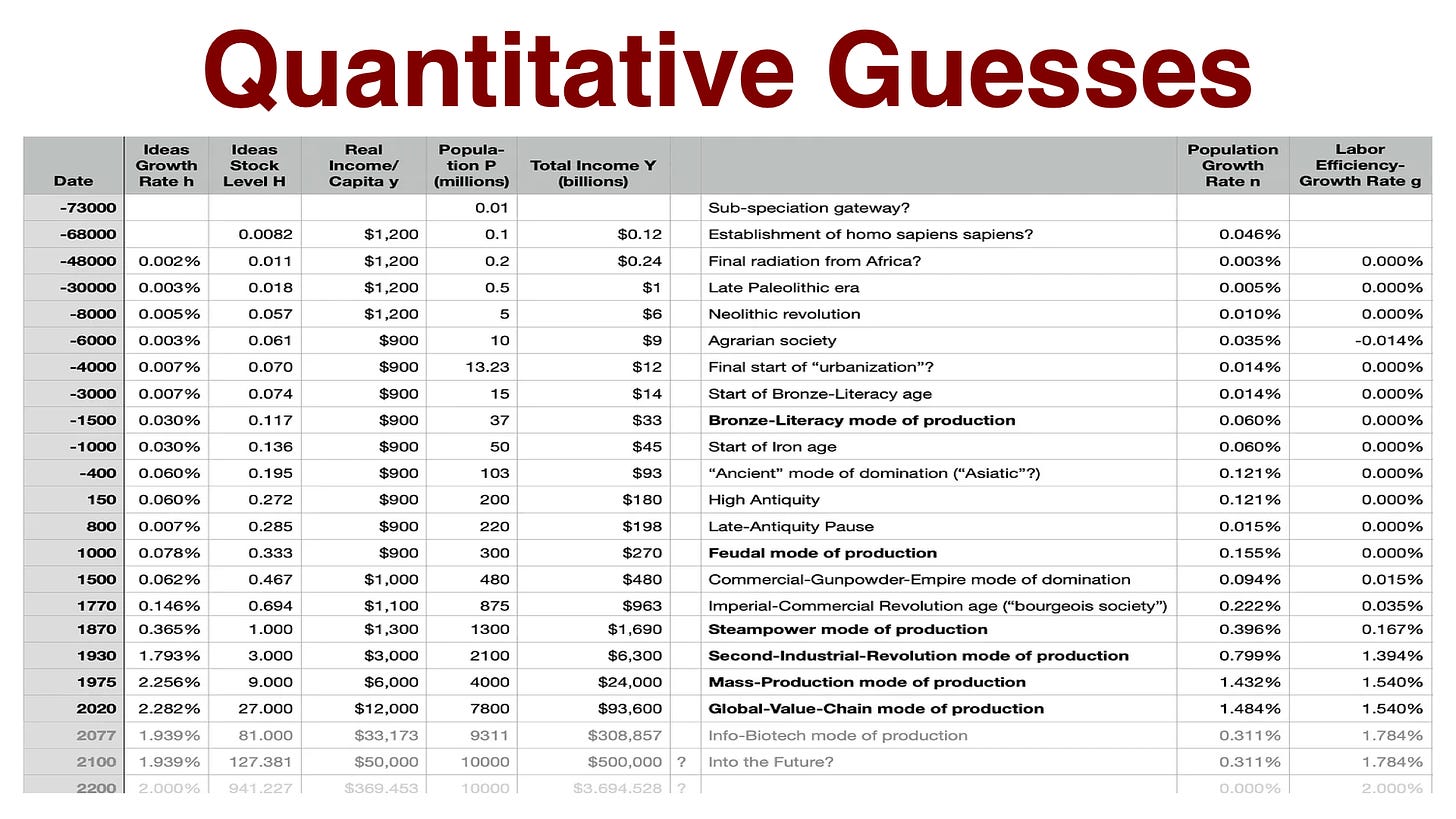

I have a more-or-less standard lecture drawing a very sharp contrast between the 0.05%/year (yes, that is only 5% per century; that is a doubling time of 1400 years) typical economic growth rate of the pre-1500 Agrarian Age and the 2%/year (yes: that is eight-fold per century; that is a doubling time of less than 35 years) economic growth rate typical of our post-1870 Modern Economic Growth Age:

Recall our table of guesses of the overall state of the human economy—global population, average productivity and living standards, our rough-guess quantitative index H of the level of human technological competence in organizing nature and productively and coöperatively organizing ourselves (productively and coöperatively: our ability to dominate and exploit each other is another and different thing than “technology”, or so I define it), and the proportional rate h at which that rough-guess quantitative index grows—since well before the Dawn of History:

Orient yourself by focusing on the rate of growth of human technological competence back in the long pre-1500 Agrarian Age, which seems to have been on the order of 5% per century.

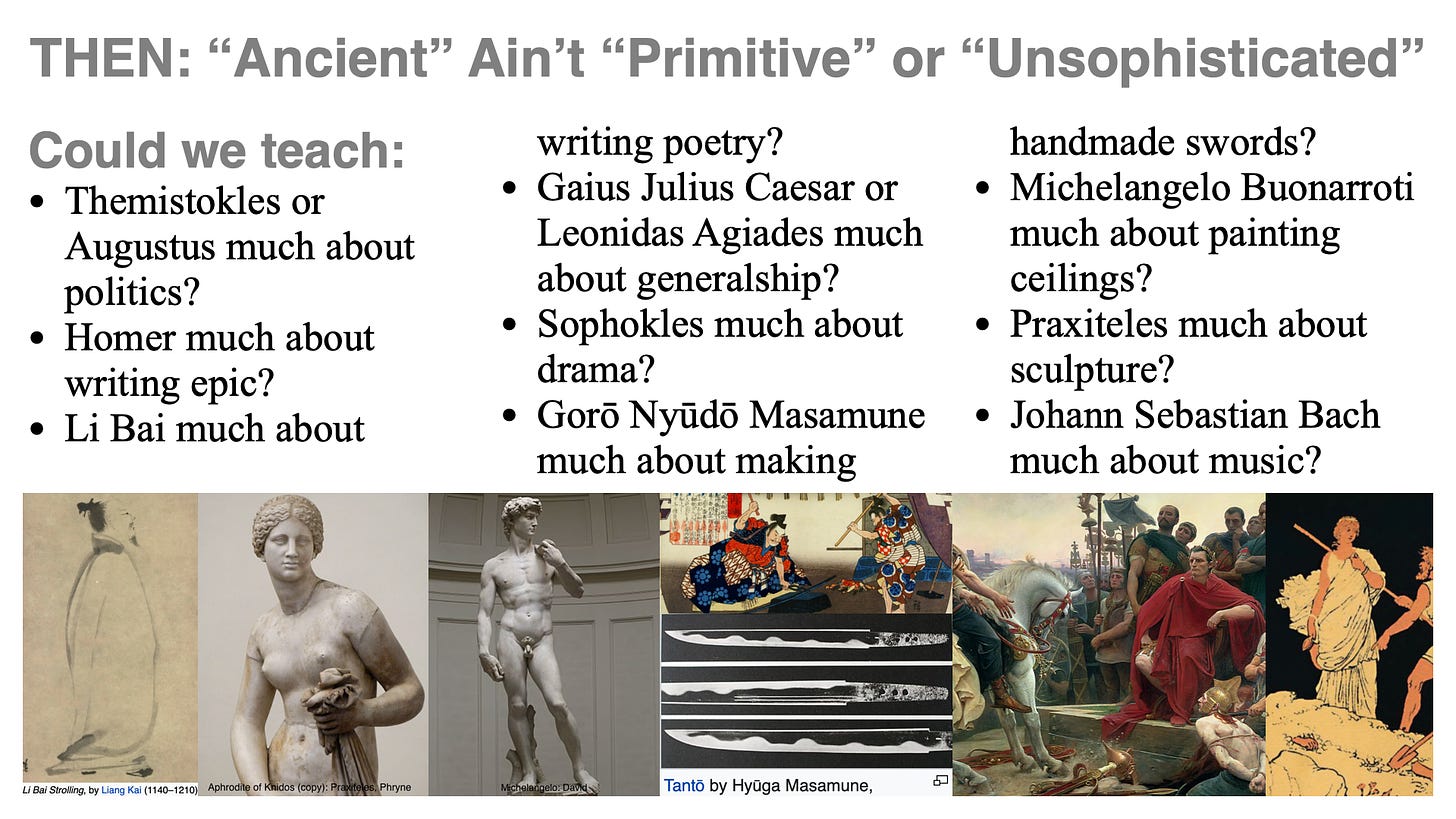

Puzzle about why: Given civilizational and cultural creativity and competence in pretty near everything else—it seems that that h might well have been different, and much higher. For the ancients were capable of astonishing feats of intellectual creativity. In rhetoric, would Barack Obama have much to teach Pericles and Demosthenes. In generalship, it certainly seems rather that Cæsar and Alexander would have had a great deal to teach William Westmoreland. In governance, our rulers and bureaucrats have a hard time matching Augustus and Trajan. In philosophy, Aristotle and Xeno. In sculpture does Rodin have anything over Praxiteles or Michelangelo? In literature—the finest play I have ever seen performed was a version of Sophocles’s Antigone, and my wife’s favorite movie is an adaptation of the comedies of Plautus. Outside of the pace of overall economic growth, and the level of scientific, technological, and engineering knowledge, the battle for superiority of the Ancients vs. Moderns still hangs in the balance. In essentials they were equal to us, for in essentials they are us.

But not in the rate of technology-driven economic growth.

And to underscore this point I have typically put up a slide:

One day I was looking at this slide of mine and noting: there are no women’s names on it.

In the histories written down in patriarchal societies, women do not typically show up as exemplars of world-class human excellence. But I thought should be able to do better. I asked myself: Who is the first woman I can think of from back in the Agrarian Age who was truly world-class along some dimension of human excellence and accomplishment?

And there she was, already staring back at me from the bottom of my slide: the Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles; or, rather, Mnesarete of Thespiai. The name means “The Remembrance of Virtue”. She was the probable model for Aphrodite in this now-lost original but much copied Classical Greek statue by Praxiteles:

There is a poem about the statue. In the poem “Paphian Kythera” means “Aphrodite” (who was supposed to have emerged foam-born from the waves and came ashore at the island of Kythera, before then traveling to and setting up her cult at the port of Paphos on Cyprus).

Aphrodite is here taking a tourist visit to Knidos to see a statue of… herself:

Paphian Kythera came through the sea to Knidos, Wishing to look at her own image; Gazing at it in its spot open on every side, She uttered: “Where did Praxiteles see me naked?” Praxiteles did not look upon that which was not allowed, But the iron carved the Paphian as Ares would wish her.

What was the dimension of human activity in which Mnesarete of Thespiai achieved world-class excellence? It is one of few dimensions of achievement truly open to women in an age of patriarchy: that of making your way in society via presenting-yourself-as-a-celebrity to a primarily male gaze.

In this, Mnesarete of Thespiai, daughter of Epicles—called “Phryne”, toad—would have had nothing to learn from our modern practitioners of this form of human excellence, like, say, Kim Kardashian. And I am not dissing people here. I am not at all dissing either of them.

If, 2000 years after your death, men are feeling enough unease and angst about your status and influence to still write poems about you trying to undermine and degrade the memory of the social power you wielded, you have managed to accomplish something. Witness Alexander Pope:

Phryne had talents for mankind, Open she was, and unconfin'd, Like some free port of trade: Merchants unloaded here their freight, And Agents from each foreign state, Here first their entry made. Her learning and good breeding such, Whether th' Italian or the Dutch, Spaniards or French came to her: To all obliging she'd appear: 'Twas Si Signior, 'twas Yaw Mynheer, 'Twas S'il vous plaist, Monsieur. Obscure by birth, renown'd by crimes, Still changing names, religions, climes, At length she turns a Bride: In di'monds, pearls, and rich brocades, She shines the first of batter'd jades, And flutters in her pride. So have I known those Insects fair (Which curious Germans hold so rare) Still vary shapes and dyes; Still gain new Titles with new forms; First grubs obscene, then wriggling worms, Then painted butterflies.

So I added her to the slide:

Ever since, in my teaching I have often paused here. I have wondered if it was time for an extended digression. Women appear in our non archæological pre-modern historical sources very rarely. It happens so rarely that we should pause and note it. And we should particularly spend time when there is enough meat in the sources for a woman to appear as a well-rounded character, rather than as a stock two-dimensional figure.

Well, in the case of Mnesarete daughter of Epicles of Thespiai, there is enough meat. And now there is—published just this February—Melissa Funke’s superb Phryne: A Life in Fragments. For Melissa has read all the things, thought all the thoughts, and done all the work. And so I can crib.

Therefore let me know give my thoughts on the subject of the life of, social power exercised by, and rôle of the presentation-of-self-as-celebrity to the primarily male gaze played by Mnesarete of Thespiai, daughter of Epicles, in Athenian society in the -300s.

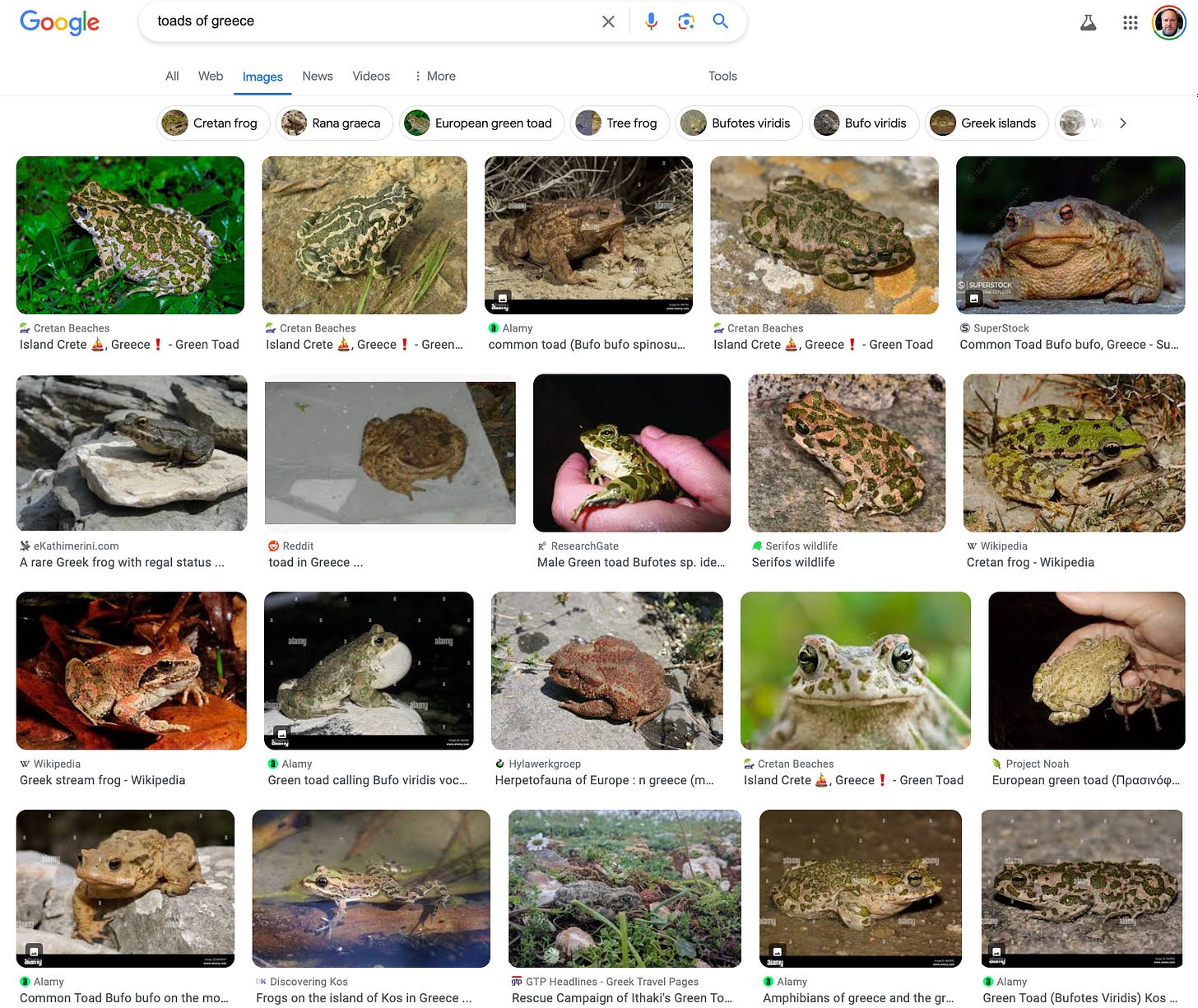

We know that Mnesarete lived primarily in Athens from the year -371 or so to sometime after the year -316. She was called “Phryne”. According to Plutarch, she got that name because her complexion was like that of a Greek toad:

Thus she did not have the ugly pasty skin of the red- and blond-headed barbarians to the north. She did not look like the fantasy of Jean-Léon Gérôme’s painting of her before the Areios Pagos:

Rather, her skin was presumably a pleasing yellow-brown, contributing substantially to her attractiveness. For it was her beauty, her wit and intellect, and her ballsiness in terms of gaining and holding substantial social power and wealth in highly patriarchal Athens of the -300s that made her notable.

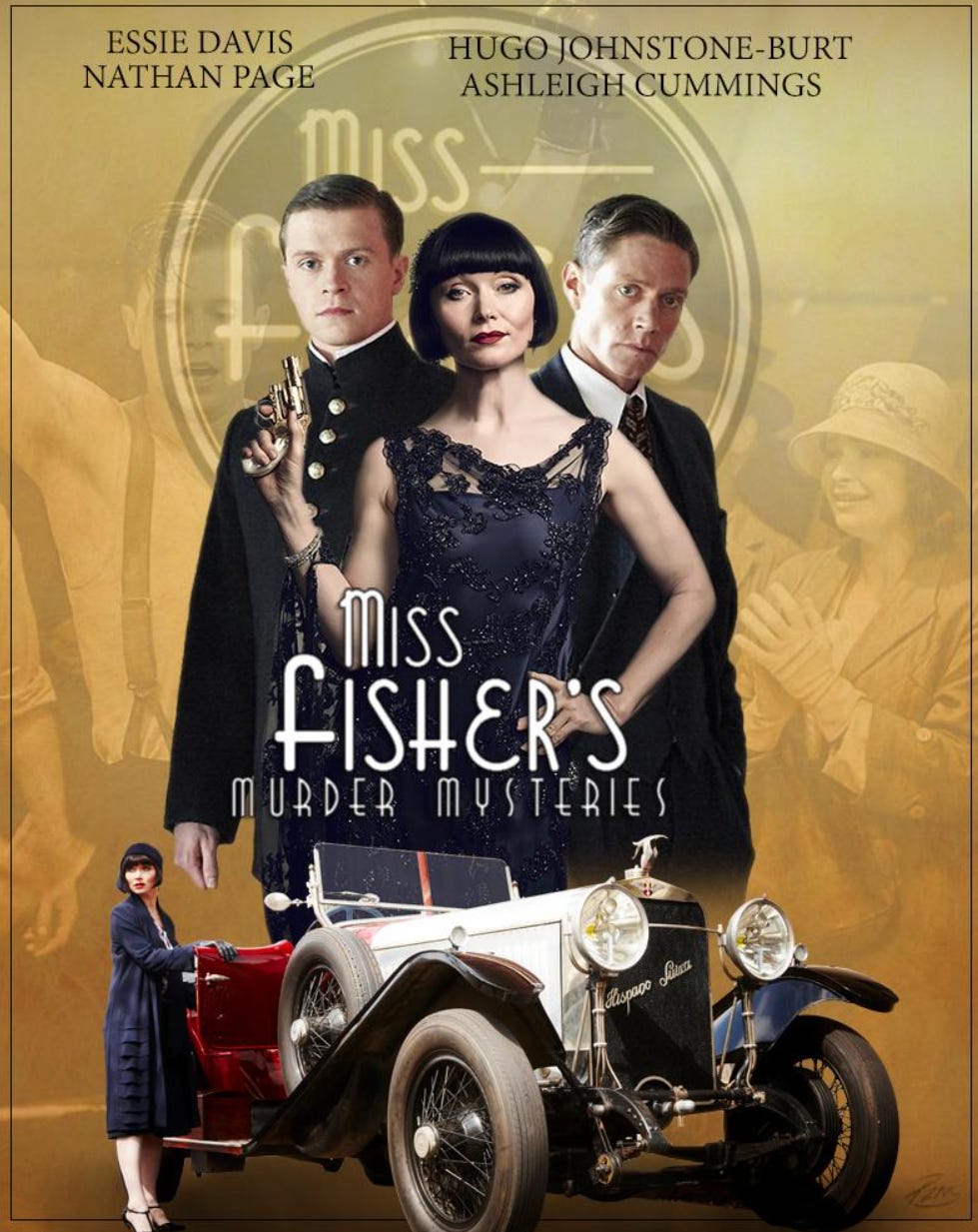

At this point I should stop and emphasize—as Melissa Funke emphasizes—that the life of the real Mnesarete daughter of Epicles of Thespiai, the real Phryne, is very close to unrecoverable. We have the woman herself. We have the woman creating an image of herself-as-celebrity to display to Athens. We have the reception of that image by her contemporaries in Athens in the -300s. We have Hellenistic authors 200 years later nostalgic for Classical Athens embroidering their own stories about Phryne. And then we have Roman-Empire authors 200 and 300 years after that in turn embroidering their own versions in their own episodes of nostalgia. All of these came down to Renaissance Europe in fragments only. And since then still other authors have run changes on the character, most prominently the appearance of a “Phyne Fisher” as a jazz-age sleuth in post-World War I Melbourne:

The total effect is as if one were trying to write a biography of the historical Alexander Hamilton if all one had were fragments from the book of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton—if those fragments had then been edited by and incorporated into works by authors several centuries in our future who were engaged in their own, different nostalgic projects about America’s founding. Thus Melissa Funke calls her a “dreamgirl”, as authors thereafter for 500 years take their dreams of her—but dreams in which, originally, she played a major part in creating—and project it onto reality as she becomes the subject of anecdotes about how Classical Athens truly was, might have been, or should have been. In many of these, in Funke’s words:

the social rules of historical Athens were suspended or even turned upside down to favor the witty women… [but] these vignettes could never represent that city faithfully, nor did they intend to. [Rather,] the authors… were harnessing the cultural capital of Classical Athens to draw attention to their literary artistry; mimesis of the past only serv[ing] to draw attention to discontinuity with it…

And the result is:

[The] melding of woman, image, and anecdote…. Larger-than-life: a stunning beauty whose appearance we can claim to know from endless copies of a monumental statue, a woman of great wit whose intellect is apparent through devastating snippets of repartee, and someone whose public presence in her own time was incendiary…. Fictionalized… Athens along with its fictionalized inhabitants… subjected to a slow and careful process of selection… governed by… generic expectations…. All… the fragments… [we have] survived through a very intentional process which must be accounted for, so if we want to understand how Phryne’s story was shaped…

So what do we truly think?

We think we know she was born in Thespiai around the year -371. We suspect that she came to Athens as a war refugee after one of the several sacks of Thespiai by the Thebans. But Melissa Funke thinks there is also the possibility that she was brought into Athens by a pimp or a madam as a child prostitute. Either way, she was probably poor when young—there is a claim in a contemporary play that she was not so high-and-mighty as she later became back when she was earning money by picking caper-buds, and presumably got laughs. She was able to elevate her status from (possibly) a foreign-born non-citzen pornē, a prostitute whose body was bought by the hour; to (possibly) a pallakē concubine-mistress, to (eventually and somehow) a hetaira, which is a courtesan? a semi-geisha? Someone who is not the non-married sexual partner and also economic dependent of a man who is a pallakē. Someone for whom what is sold—and not sold for cash, but rather offered in return for valuable gifts—is not sexual access to her body but rather permission to woo her. And so stories were told of the lament of the ultimately rejected:

I, the unlucky, fell in love with Phryne… [and] despite spending absolutely everything, each time at her door, I was shut out'...

Plus the permission to woo is given on a sliding scale—or so Funke cites Athenaios for stories like:

She asked… Moerichus for a mina (roughly one hundred drachmai)…. When he replied that she had only charged a foreigner two gold staters just the day before, she told him to wait around until she was in the mood...

And yet hetarai were also supposed to be greedy for things that can be turned into hard cash: “Is Phryne not completely like Kharybdis than when she grabs a ship-captain and swallows him down, ship and all?…” Hetairai were “megalomisthai”—very large earners.

Phryne was thus fitting herself into a pattern. When Phryne was about six years old or so, Xenophon wrote a book, Recollections of Sokrates, in which he relays a conversation between Sokrates and the hetaira Theodote. Xenophon describes her as a great beauty, who “spend[s] time with those who tempted her”. Sokrates asks: how does she make a living? “If someone who is dear to me wants to do well by me, that is my livelihood”. The resource-transfers are part of gift-exchange between friends. And the very way that Xenophon structures the dialogue points to an important element of the hetaira: a hetaira is someone who likes to engage in witty, friendly, and flirty dialogues—even with philosophers who see their rôle as that of gadfly. Great beauty, accompanied by great wit, able to subvert hierarchy and get the better of powerful men via well- and quick-chosen words, and very very choosy.

Beautiful, witty, greedy, frequently drunk, choosy—and sometimes with a heart-of-gold—that is the stock literary character of the hetaira, alongside the trickster clever-slave pseudolus and the bragging soldier miles gloriosus.

But Phryne goes beyond the two-dimensional theatrical-stock hetaira character in her presentation-of-self, and thus in her attainment of celebrity, and hence wealth and social power.

For one thing, for Phryne “choosy” extends to more than sex. As Funke says, while some of the Phryne-stories are standard hetaira tropes “greed and over-indulgence”, others are “unique to her”. Unique to her is that you could not easily but you could sometimes see her body entire. Funke quotes Athenaios:

“She was in the habit of covering herself up with a clingy shift and she didn’t use the public baths. But when it was the Eleusinian festival or the Poseidonia, in sight of all the Greeks she set aside her dress, let down her hair, and went into the sea…”. Phryne… protects her body from public view, but also selects specific events at which… nudity will have maximum impact…. [The] religious… festivals makes her public nudity somehow divine, while potentially offering a legitimate reason for her to bathe publicly…. Apelles and Praxiteles turn her into a goddess in response, creating a triangulation between woman, goddess, and artwork...

Making her full beauty only visible in context with religion, and thus sacred, semi-divine, mind-overpowering was part of her presentation-of-self, part of her celebrity. And being a model for the Goddess of Love herself was a further amping up of that part of her presented persona: “‘Where did Praxiteles see me naked?’/Praxiteles did not look upon that which was not allowed,/But [via Phryne] the iron carved the [statue of the] Paphian as Ares would wish her…” Taking on the aspect of a god, with the power to drive men mad with what she does not show day-to-day—that is a truly ballsy move in the social power-acquisition game.

It is not just Praxiteles’s Aphrodite of Knidos, the first large-sized three-dimensional female nude in ancient Greek art, that Phryne is supposed to have modeled for. Pausanias wrote that there was a Praxiteles statue of Phryne at the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, commissioned by the people of Thespiai. And there was supposed to be a state of Phryne in her own persona placed alongside statues of Aphrodite and Eros in Thespiai. Plus she was said to be the model for Apelles’s painting of Aphrodite Anadyomene.

And it worked. She did become, it is said, one of the wealthiest women in Greece. She was, the story goes, rich enough to offer to pay for the rebuilding of the city wall of the city of Thebes—but only on the condition that the Thebans inscribe on it: “Alexander made this go limp, but Phryne the hetaira made it stand erect again”.

That is the story, at least.

Are these stories true? Funke wisely observes that stories like:

the hetaira besting the intellectual or the philosopher rejecting a great beauty makes for… comedy, but both groups… could move through different parts of society because of their flexible and shifting statuses… with their ability to draw an elite clientele or circle of followers key to long-term success and independence from mainstream society. Consequently, while the anecdotes… may not be literally true, they point to real dynamics at play for both hetairai and philosophers, by which Phryne’s own relationships would certainly have been shaped…

So far this is the story of a woman rising from war refugee (or perhaps child slave-prostitute) to a position of substantial social and economic power to live her life as she wished, doing so in a highly patriarchal society without any supporting prominent male relatives, and doing so by her wit, charm, and beauty. But there is a reason the Greek saying was “call no man happy until he was dead”. Themistokles was outlawed and banished from Athens, ending his days as a client of the Great King of Persia. Demosthenes poisoned himself rather than submit to the possible vengeance of the Makedonians. Sokrates drank the hemlock. Leonidas made a dog’s breakfast of the delaying action at Thermopylai, losing his own life and the lives of all 4,000 of his command, while the Persians buried only about 1,000 of their troops on or near the battlefield.

Phryne was, the story goes, put on trial for impiety, asebeia, the same crime as Sokrates, before the Areios Pagos. She had, supposedly, held a shameless ritual profession, organized debauched mixed-sex religious meetings, and tried to introduce a new cult, that of Isodaites, into Athens. Euthias, one of her former lovers—possibly driven mad by jealousy—brought the charge. The orator Hypereides defended her.

There are many versions of the story:

Phryne exposed her own breasts or her breasts and her pudenda to the court at the climax of the trial, and was acquitted.

Hypereides exposed Phryne’s breasts or her breasts and her pudenda to the court at the climax of the trial as part of his courtroom strategy, and she was acquitted.

Hypereides saw that his closing argument had failed to convince the jury, and so exposed her breasts or her breasts and her pudenda to the court at the climax of the trial as a last resort,

Phryne personally pleaded with each of the jurors at her trial for them to save her life, and with her tears secured her acquittal.

But all agree that she was acquitted. And she fades out of history after 316, having survived to at least 55, presumably still in Athens and still very rich.

Funke sees the stories of Phryne as:

titillating, yet… also hint[ing] at the tenuous position of a foreign-born sex worker in a society structured to privilege male citizens…. Stories that at first glance seem to highlight Phryne’s place… and the power of her beauty upon closer inspection reveal the danger of being a prominent woman…

Yes, there were dangers in being a prominent woman. But the biggest danger was that something would go wrong, and you then would become a non-prominent woman. And at least until you lost your prominence, you did have and exercise considerable social and economic power.

Funke concludes by saying:

Phryne did exist and could have moved through fourth-century BCE Athens in many of the ways I have explored here, [but] the Phryne that remains for us is only an idea…. How Phryne was portrayed over centuries allows us to grasp the very real forces that have shaped women's lives and our understanding of them…. During her own lifetime, Phryne led a lifestyle that did not fit comfortably into traditional roles available to women and it is likely that she was brought to court as a result of that discomfort, but it t accrue a large fortune and the fame that brings her to us today…

I think that is right.

So if you are at all interested in this kind of thing, go get and read: Funke, Melissa. 2024. Phryne: A Life in Fragments. London: Bloomsbury Academic. <https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/phryne-9781350371873/>.

So now let me stop cribbing from Funke. What do I think? I think Phryne is an excellent example of a human playing a very weak hand with an enormous amount of intelligence and skill, and so gaining a considerable amount of freedom for herself and social power to direct resources for a woman by virtue of her success at the profession of presentation-of-self-as-celebrity. Attaining the summit of human excellence possible in her profession. A gutsy and successful lady.

Yes, the Hellenistic and Imperial Roman intellectuals who have propagated the fragments of her life and the associated fictions down to us were about a sexy, witty lady. But they would not have heard of her at all had she not managed to first win the social game to become a celebrity. Even with the propagation of her life and legends going with the grain, you have to have done a really good job and been very successful to get people like Alexander Pope trying to neg you more than 2000 years later.

And what we can see of her life serves, I think, as a very good introduction to how a woman could live her life under the constraints of ancient patriarchy.

But there is no way that I am going to be able to find the time to teach this in the fall.

References:

Davidson, James N. 1997. Courtesans and Fishcakes: The Consuming Passions of Classical Athens. London: HarperCollins. <https://archive.org/details/courtesansfishca0000davi>.

Fugard, Athol, John Kani, & Winston Ntshona. 1976. Sizwe Bansi Is Dead; &, The Island. New York: Viking Press. <https://archive.org/details/sizwebansiisdead0000fuga>.

Funke, Melissa. 2024. Phryne: A Life in Fragments. London: Bloomsbury Academic. <https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/phryne-9781350371873/>.

Plautus, Titus Maccius. -197 [1897]. Mostellaria. Ed. Frank R. Merrill. London: Macmillan; New York: St. Martin's Press. <https://archive.org/details/mostellaria00gaingoog>.

Plautus, Titus Maccius. -191 [1916]. Pseudolus. Trans. Paul Nixon. London: W. Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. <https://archive.org/details/plautuswithaneng01plauuoft>.

Plutarch. ca. 100 [1936]. “On the Answers of the Pythian Oracle”. Moralia. Vol. V. Trans. Frank Cole Babbitt. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. <https://archive.org/details/plutarch-isis-osiris-loeb>.

Pope, Alexander. 1736. “Phryne”. Miscellanies. Vol III. London: Benjamin Motte. <https://allpoetry.com/Phyrne>.

Sondheim, Stephen, Burt Shevelove, & Larry Gelbart. 1962. “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”. New York: Alvin Theatre. <https://archive.org/details/AFunnyThingHappenedOnTheWayToTheForum>

Sophokles. -442. [1888]. Antigone. Trans. R.C. Jebb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. <https://archive.org/details/tragediesofsopho00sophiala>.

Wikipedia. “Phryne”. Accessed December 13, 2022. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phryne>.

3762 words

Very nice! Now do Hypatia.

Murasaki Shikibu comes to my mind as an example of a very accomplished ancient woman if you’re looking. Also Plato among others seems to have been very impressed by Sappho of Lesbos - but only a tiny taste of her work has survived for us to try and see what the fuss was about.