American Upper Middle-Class Existence & Its "Discontents[?]"

Emily Stewart has written a very interesting piece; but it seems to me to miss a lot of what is really going on here.

“The country’s upper middle class isn’t used to precarity”, writes Emily Stewart, in Vox. Furthermore: “the economy’s winners feel like losers”.

In what sense could this be true?:

Emily Stewart: When the economy’s winners feel like losers: ’Part of what’s at play is the ever-increasing costs of housing and housing and housing, which have caused upper-middle-class Americans to experience housing for years. Other issues are more recent, like housing, which everybody hates. What this amounts to is people who aren’t used to financial insecurity feeling uneasier than they’re accustomed to. The bottom hasn’t fallen out for them, but the ground is less solid in a way it hasn’t been in the past. America’s semi-rich are feeling semi-bad, and they do not like it…

What is going on here?

Step back: What is this “upper middle class”? This is always a dicey question. This is a particularly dicey question in America, where on the one hand we have no members of the working class—but only temporarily embarrassed millionaires—and on the other hand even the rich are desperate to be, really, middle class strivers, in their deluded minds at least. The “middle class” is thus almost everyone. So when Emily Stewart writes about the “upper middle class” she is really writing about what would in other societies be the middle class.

Who is in the middle class?

Throughout history, the middle-class has never been the median. The middle-class has never even been the average. The middle-class has been those who are of middle status: they are not, or do not think of themselves, as being rich in the sense that they do not see themselves as possessing the immense social power to manipulate nature and command others that the rich have; and yet they are not the working joes and jills for whom crossing the boss can be a disaster.

So figure that the middle class—that Emily Stewart’s upper middle class—is composed of those outside the top 1% who are in the top quarter of the income distribution, or perhaps it is those who either see a path to being in the top 10% of the distribution in their peak earning years, or who have attained the top 10% in their peak earning years.

Now that such people feel precarity is not completely new in historical perspective. Remember George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier?

I was born into what you might describe as the lower-upper-middle class… [a] mound of wreckage left behind when the tide of Victorian prosperity receded… between £2000 and £300 a year…. To belong to this class when you were at the £400 a year level was a queer business, for it meant that your gentility was almost purely theoretical…. Theoretically you knew all about servants and how to tip them, although in practice you had one, at most two, resident servants…. Rent and clothes and school-bills are an unending nightmare, and every luxury, even a glass of beer, is an unwarrantable extravagance. Practically the whole family income goes in keeping up appearances…. The poor devils… struggling to live genteel lives on what are virtually working-class incomes… are forced into close… contact with the working class, and… this attitude… of sniggering superiority punctuated by bursts of vicious hatred. Look at any number of Punch during the past thirty years…. Your gentility… is the only thing you have…. Everyone who has grown up pronouncing his aitches and in a house with a bathroom and one servant is likely to have grown up with these feelings…. Hence that queer watchful anxiety lest the working class shall grow too prosperous…. For miners to buy a motor-car, even one car between four or five of them, is a monstrosity, a sort of crime against nature…. The notion that the working class have been absurdly pampered, hopelessly demoralized by doles, old age pensions, free education, etc., is still widely held…

“Poor devils… struggling to live genteel lives on what are virtually working-class incomes” with “one, at most two, resident servants”. Yes, relative prices were very different: in her old age Agatha Christie did say that her younger self had never thought she would be so rich as to own a motorcar, or so poor as not to have live-in servants.

Things are very different now in the United States than they were in Britain in the grinding deflationary 1920s and then the Great Depressed thirties.

But history is rhyming here.

Step back again:

median household earnings are only up by 20% since 1980,

average household earnings are up by 51% since 1980,

90%-ile W–2 earnings up by 63%,

98%-ile up by 94%,

top 1%-ile up by 265%, and

top 0.1%-ile up by 465%—and most of top 0.1%-ile income never touches a W–2, and has grown much faster than W–2 income—since 1980.

The general pattern that had held from 1870 to 1980 that the incomes associated with slots in the American hierarchical income distribution roughly doubled every 40 years has been true only for the top 5% of income slots since 1980. And for the top 1%-ile incomes have not doubled, but nearly quadrupled. And for the top 0.1%-ile, incomes have not even merely quadrupled but nearly sextupled.

One can think of non-precarity as being composed of three things:

I am living almost twice as well in a material sense as my parents did.

There is no chance of the gap closing between my income and status and those who do not deserve the good things—either because (then) they did not have the right lineage and accent, or (now) they have not punched their semi-meritocratic ticket properly.

I am keeping pace with the lucky who are significantly above me in income and social power.

In the years since 1980, (1) and (3) have disappeared from the experiences of those below the top three percentiles (and when you are young a certain road from where you are into not just the top 10% but the top 3% is rarely visible). That leaves a great deal resting on (2): on being very secure against downward mobility. In the past (2) was made more secure by a tide of immigrants that put a great deal of upward pressure on the economic value of full literacy in English, and by a belief that housing was affordable when young and was bound to appreciate massively in value. Today—at least in California and in Texas and in Florida and New York—it is bilingualism that seems more likely to open doors, and getting on the housing-appreciation train that seems blocked.

So let’s give the mic to Emily Stewart again:

In America’s unequal society, people near the top experience a level of economic segregation that is beneficial to them, and also precarious. They fear losing grasp of what they view as limited but necessary resources unavailable to the broader population, which is why they shell out money on private education and extracurriculars to, as philosopher Matthew Stewart describes it, “optimize” their children…. Higher prices are making it harder for them to be able to buy their way into getting a better deal as consumers and separating themselves out from the rest of the economy, whether that means paying to have a better seat on a flight or opting for concierge health care. Skyrocketing child care costs mean they may not be able to pay for their kids to have the best of the best. Americans are souring on the value of a college education and increasingly wondering if the degree they’ve paid for to preserve their social status or launch themselves into a higher one is worth the cost…

Stewart’s reliance on Richard Reeves on “economic segregation” is perhaps not the wisest move, as he has always been someone who sees what he wants to in the data, rather than what is there. Inflation does not, on average, diminish people’s economic and social resources—but it does feel like the economy has broken its social contract with you, and causes great anxiety and the fear (even if not the reality) that things are precarious.

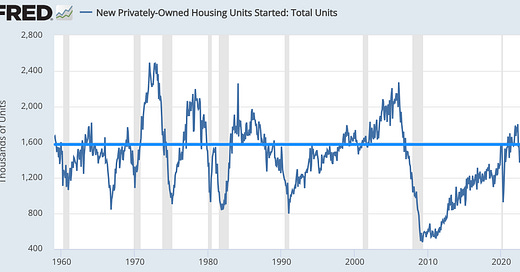

Certainly the housing component of “thriving” in the upper middle class is a real obstacle, 1/3 because the country has filled up without our building additional transportation infrastructure, and 2/3 because the Bush, Obama, and Trump Treasuries and OFHEO never cared enough to fix housing finance after the 2007–8 financial crisis:

A bigger country. But less housing being built in the 2000s than in the 1950s.

Neither college nor childcare costs have “skyrocketed” enough to have a material impact on resource flows. But there is, perhaps, a reality in the fear that the Schumpeterian creative-destruction that is the source of our collective wealth is coming for white-collar work and so about to destroy the value of semi-meritocratic ticket-punched credentials in a way that it never has before.

So we are left with a “precarity” of America’s upper middle class composed of:

Housing,

The fear that Schumpeterian creative-destruction is coming for the white-collar jobs oneself and one’s children are supposed to have a secure right to because of their successful semi-meritocratic ticket punching,

Plus, as Zvi Moskowitz puts it, those who want to be “thrivers’ are consuming 53% more in the way of real quality-adjusted commodities than their counterparts did in 1980, but are comparing themselves to a 75% higher standard.

Again, the mic to Emily Stewart:

The poorer… inch[ing] closer to the richer, can cause unease among the richer…. accustomed to things being quite a bit better for them…. Sam Deutsch, a 27-year-old recent Harvard Business School graduate, says the job market for his class is worse than it was a year ago, when everything was hot, hot, hot. He feels lucky enough to have landed a job in October, but many of his classmates haven’t—at least not the ones they thought they were in line for when they signed up to get their MBAs at Harvard. “Part of what they’re selling is this idea that you’ll have this stamp on your resume and you’re not really going to be in a position where you’re ending up with no real job prospects,” he said…. His brother, a chef with no formal kitchen training… quit his job without a backup plan… and quickly landed a new gig making 50 percent more. In the Harvard social bubble, it can feel like a recession, because everybody’s saying it’s hard to find a job and companies aren’t hiring…. Things are still better for the upper middle class, just not as much as historically has been the case. People are averse to loss, including of their positioning relative to others…

My first reaction would be if there is no way in hell that graduates from Harvard with MBA's should be in any way jealous of a hot labor market for chefs. Only a belief that they are dissed. If in some sense distinctions are not maintained, can make such a thought, understandable. The HBS MBA market is one subject to fads and fashions in the extreme, and in recent years, the flow to finance, and to somewhat dodgy tech as well as to big tech has been so strong that many sectors that would want to hire Harvard MBAs have not even been trying to do so. No: Harvard MBA’s are not “precarious”—they signed up for a very high mean and a wide variance in career outcomes.

In my view, however, the big status insult to America's upper middle-class is not the fact that incomes of upper middle-class slots in the income distribution have not doubled, but only increased by 2/3 over the past 40 years. In my view, however, the big status insult to America's upper middle class is not that those "below" them are doing "too well".

In my view, the big status insult to Americas upper middle-class is the existence of our current class of plutocrats: the top 0.01% of the income distribution hogging not the 1% of total income they had 50 years ago but instead now 5% of total income. And then there is the rest of the top 0.1%: those who hogged 2% of America’s income in the 1970s and 6% now. That means we have a top 0.01% today with 500 times average incomes compared to 100 times average incomes then. That means we have a rest-of-the-top 0.1% today with 50 times average incomes compared to 20 times average incomes then.

Thus to—relatively minor, if we are being realistic—fears about your own and your children’s economic and status future are added the obvious fact that you cannot claim that you have “made it” in any real sense, when you look at the 16000 families in the top 0.1%.

I have always thought about upper middle class precarity in terms of the way a string of bad luck really can throw you out of the upper middle class entirely. It is just much easier, in America, to go from riches to rags, compared to the way things work in actually-civilized countries. Say one member of a couple has an expensive medical crisis (and oops, you have one of those High Deductible plans so you really are personally responsible for five figures!) at the same time as the other member has been laid off. You can end up rapidly losing your home and vehicle, which then makes it extremely difficult to claw your way back into the ranks of normal middle class life. We have increasingly leveraged our middle class -- housing and education and so on have higher sticker prices, but incomes are high and interest rates are low, so the banks come along and say, "Not to worry, you can finance everything and your rising income will keep up with the payments." And that's all fine and dandy until your income happens to take a hit, and you discover that leveraging up a family carries the same kind of risk as leveraging up a business in a buy-out. (See the recent Instant Pot story.)

You can see the effects of this in the rates of business formation. In a country where _failing_ is unpleasant, but doesn't mean your children starve in the streets, a lot more middle-class people are willing to take a flyer on an idea: https://www.inc.com/magazine/20110201/in-norway-start-ups-say-ja-to-socialism.html

This is also tied up with the "401(k) revolution". We have systematically moved risk off of companies, onto families. We really should shift from these individualized private accounts (which seem to mainly exist to allow the custodians to harvest exorbitant fees), to having the main nexus of retirement funds be target-date tranches of a Sovereign Wealth Fund. Administer access through postal banking (along with a basic checking account), and get people started on their savings through Cory Booker's Baby Bonds / Universal Basic Wealth concept, with bonus funds going to low-income / low-wealth parents.

I think maybe you are missing most of the story because it’s not about income or wages but about things which are much more nebulous about the life you get to live…things like 1) the subjective feeling of uncertainty—hard to measure but real, and caused by the 2008 crash and various other events and 2) the inability of some to buy or rent. So professionals where I live would have to part with 40-50% of take-home pay to rent even a crappy one bedroom apartment. Plus, it’s EXTREMELY hard to break into professions and find lasting security. Maybe 1-3 is supposed to measure that but I don’t think it’s relative or comparative with those above or below you so much as relative or comparative with the previous generations. E.g., my grandparents had a sweet little house and nice little vacations and a nice little car and sent their kids to college on one income, etc. And got to retire at a normal age ALL WITHOUT GOING TO COLLEGE. Then my parents had the same but both parents went to college and had two income earners…but now here are we…we cannot get a house, we went to grad school, we can barely afford groceries. (I am not speaking of myself but people I know.)