An Earlier DRAFT Version of My “Singularity in Our Past Light Cone” Meditation from “Slouching Towards Utopia”, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-07-06 We

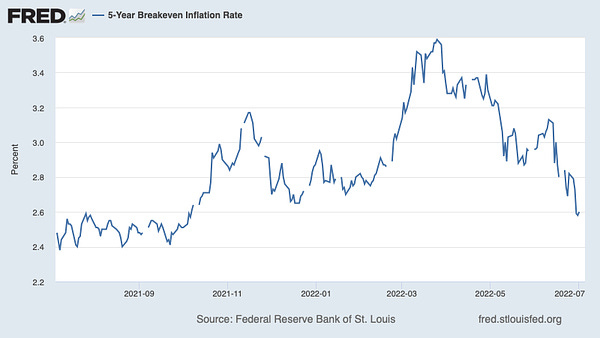

CONDITION: No, Inflation Is Not Getting Entrenched

The odds that expectations of higher future inflation are getting entrenched in the labor and product markets while skipping the bond market are extremely, extremely low:

Paul Krugman: ’Mr. Market seems to have decided that stagflation isn’t happening after all <https://t.co/49jmrg0Ajw>…. The point is NOT that the market knows. Clearly, it often hasn’t. Instead, we’re talking about whether continuing inflation is getting entrenched in expectations. the way it was in the 70s…

And I have a closely related piece in the Economist:

Brad DeLong: By Invitation: The Economist: ‘What America can learn from its past bouts of inflation In 1947 and 1951 the problem went away by itself. In 1920 the Fed tightened too much… https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2022/07/05/brad-delong-asks-what-america-can-learn-from-its-past-bouts-of-inflation?etear=nl_today_3>

FIRST: An Earlier Version of My “Singularity in Our Past Light Cone” Meditation from “Slouching Towards Utopia”…

As Cosma Shalizi (2010) Says, “The Singularity Is in Our Past”: Look at the bleeding edge of urban North Atlantic or East Asian civilization, and you see a world fundamentally unlike any human past. Hunting, gathering, farming, herding, spinning and weaving, cleaning, digging, smelting metal and shaping wood, assembling structures–all of the ‘in the sweate of thy face shalt thou eate bread’ things that typical humans have typically done since we became jumped-up monkeys on the East African veldt–are now the occupations of a small and dwindling proportion of humans.

And where we do have farmers, herdsmen, manufacturing workers, construction workers, and miners, they are overwhelmingly controllers of machines and increasingly programmers of robots. They are no longer people who make or shape things–facture–with their hands–manu.

At the bleeding edge of the urban North Atlantic and East Asia today, few focus on making more of necessities. There are enough calories that it is not necessary that anybody need be hungry. There is nough shelter that it is not necessary that anybody need be wet. There is enough clothing that it is not necessary that anybody need be cold. And enough stuff to aid daily life that nobody need feel under the pressure of lack of something necessary. We are not in the realm of necessity.

What do modern people do? Increasingly, they push forward the corpus of technological and scientific knowledge. They educate each other. They doctor each other. They nurse each other. They care for the young and the old. They entertain each other. They provide other services for each other to take advantage of the benefits of specialization. And they engage in complicated symbolic interactions that have the emergent effect of distributing status and power and coordinating the seven-billion person division of labor of today’s economy. We have crossed a great divide between what we used to do in all previous human history and what we do now. Since we are not in the realm of necessity, we ought to be in the realm of freedom.

But although we have largely set these post-agrarian post-industrial patterns for the next stage of human history, the human world of this next stage is only half-made. The future is already here–it is just not evenly distributed. Of the 7.2 billion people alive in the world today, at least 25% billion still live lives that are hard to distinguish from the lives of our pre-industrial ancestors. Only 5% of today’s world population lives in countries where income per capita is greater than $40,000 per year; only 10% lives in countries where income per capita is greater than $20,000 per year.

The bulk of the world’s population is on the stairway to modernity. The patterns are set. The top of the stairway is visible–although it is not clear which top we shall reach: many possible tops are immanent in the patterns. Nevertheless, the climb will be hard. And that is what much of the history of the twenty-first and twenty-second centuries is likely to be about.

So how did this great transformation happen? And how did the way it happened shape who we are now and who we will be in the future?

The traditional tools, practices, patterns, and molds of history are not as much help in telling this story as one might hope. The history of how the world was greatly transformed is primarily economic and technological, and secondarily political and social. But historians are not used to placing the economic and technological in first place. In the study of any period back before 1800, there is no way that economic history can be seen as even one of the principal axes. Before 1800, most history at even the century-level–let alone the decade-level or the year-level–could not be economic history. History is change. And before 1800 economic factors changed only slowly. The structure and functioning of the economy at the end of any given century was pretty close to what it had been at the beginning.

The economy was then was much more the background against which the action of a play takes place than like a dynamic foreground character. Changes in humanity’s economy–how people made, distributed, and consumed the material necessities and conveniences of their lives–required long exposures to become visible. Economic history could be–indeed, had to be–a specialized ‘long duration’ history. It required a scope of perhaps 500 years, if not more, to be properly placed in the foreground of any historical canvas. And even then the story told was of recurrent patterns and cycles rather than development and change.

But since 1750 or so things have been different. The pace of economic change has been so great as to shake the rest of history to its foundation. For perhaps the first time, the making and using the necessities and conveniences of daily life–and how production, distribution, and consumption changed–has been the driving force behind a single century’s history. Even in the most long-established of professions, the pattern and rhythm of work life today is so very different from that of our ancestors as to be almost unrecognizable. It is these changes in production and also in home life and consumption, and the reactions to them, that make up the center ring action of the history that has made us who we are.

This post-1750 history takes place in two stages. The first stage is the nineteenth century: the century of the British Industrial Revolution. Call it 1750-1870. It opens up the possibilities. The second stage is the twentieth century. Call it 1870-2010. It sets the patterns into which the human world is likely to grow in the future.

LINK: <http://bactra.org/weblog/699.html> Cosma Shalizi (2010): The Singularity in Our Past Light-Cone (November 28)

One Video:

One Image:

Very Briefly Noted:

David Brin: Worlds of David Brin <https://www.davidbrin.com/>

Matthew Burgess: Five Things You Need to Know: ‘Joe Biden may announce a rollback of some US tariffs on Chinese consumer goods this week… <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2022-07-04/five-things-you-need-to-know-us-tariffs-china-biden-bitcoin-japan-energy?cmpid=BBD070422_MKT>

Pia Owens: Negotiation Tips for Writers & Creatives <https://newsletters.theatlantic.com/i-have-notes/62bf4efb9fb382002053e22e/negotiation-tips-writer-author-publisher/>

Matthew Levine: Archegos Analyst Wants His Money Back <https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2022-07-05/archegos-analyst-wants-his-money-back#xj4y7vzkg>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Jon Slade: ’The power of the Financial Times…

Liz Cheney: ’Closing statement in… debate among the Republican candidates for representative from Wyoming. Watch the whole thing… <

Stephanie: ‘The $12B in cash Tesla raised in 2020… why they were burning through…

Harold James: All That Is Solid Melts into Inflation

Matthew Continetti: Lean Out with Tara Henley: ‘Once the financial crisis occurs in the fall of 2008, a real disgust that the Republicans had colluded in the bailout…

Director’s Cut PAID SUBSCRIBER ONLY Content Below:

Paragraphs:

Tesla shipped 1 million cars in 2021. But what will be their scale of operations at which they will actually have positive cash flow, and can they get there with Elon at their head?

Stephanie: ‘The $12B in cash Tesla raised in 2020… why they were burning through cash…. Wasting money is a sport at Tesla…. SG&A grew 44% YoY, in part “due to $340 million of additional payroll tax due to our CEO’s option exercises” and another $72M from a 2018 performance award…. The factories are money furnaces, but what exactly are they getting for burning this money? Texas is underwhelming, Berlin is a nightmare, and lawsuits abound from Fremont…. Their net income rise from 2019–2021 is incredible! Yet they can’t seem to keep any cash. No matter how much they raise they spend more with nothing meaningful to show for it. Where are the new models? Where are the upgrades to the current models? Why are they firing 10% of the staff? Why all the “bankruptcy” & “furnaces” talk? Tesla is run by someone who isn’t qualified and has terrible judgement. They should have ample cash but they don’t…

LINK:

I cannot help but think this is wrong. Hyperinflation is a fiscal phenomenon. But moderate inflation is a monetary and a structural phenomenon:

Harold James: All That Is Solid Melts into Inflation: ‘Policymakers in Western industrialized countries would do well to remember that periods of high inflation historically have led to much bigger problems. By trying to bind societies together with money, central banks have repeatedly sown the seeds of broader political and social dissolution…. The debates of the 1970s… raised doubts about the sustainability and legitimacy of the Western model of democracy…

Very, very disappointed in the Biden administration here: “vaccinate the world” and “start the booster train” were the obvious moves starting January 2021. But they did not happen:

Matthew Yglesias: We’re Getting an Omicron-Optimized Booster Many Months too Late: ‘We’ve gone from the impressive technical achievement of rolling out the original vaccines in record time to a sorry situation in which the FDA is authorizing Omicron-optimized boosters only after Omicron has vanished from the earth…. As Eric Topol writes, “it took more than 7 months for the Omicron BA.1 booster to be tested, a delay that is exceedingly long and unacceptable relative to the timing of validation and production of the original vaccines in 10 months during 2020.” Slowly updating vaccines to chase variants that are already in the rearview mirror is not an acceptable global Covid strategy…

LINK:

Bailing out homeowners would have been a big political win. Bailing out banks… not so much:

Matthew Continetti: Lean Out with Tara Henley: ‘Once the financial crisis occurs in the fall of 2008, a real disgust that the Republicans had colluded in the bailout program. And so, after George W. Bush leaves office, and Barack Obama arrives, conservatism and the right becomes almost entirely populist. Anti-elitist. Anti-liberal elite—but also very anti-conservative elite…. It’s a Trump party now…. They want to be on the offensive against the cultural left. They want to fight the cultural left. Doesn’t matter if they win… they really just want to fight…. Reagan Republicans. People like me. We’re still around. We’re not in control…. There is a third group… the Ultra-MAGA…

LINK:

Matthew Levine is a national treasure:

Matthew Levine: Archegos Analyst Wants His Money Back: ‘Archegos’s assets grew from about $4 billion in 2020 to roughly $36 billion on March 22, 2021; by March 29 they were roughly zero…. But what if, on March 30, you could look around at the rubble and decide to withdraw what you had in the fund as of March 22? That would be pretty good, right?… Te employment agreements apparently included a 30-day lookback option: If you quit on March 30, you could get paid your balance as of Feb. 28…. Here is a wild lawsuit filed by Brendan Sullivan, a former managing director at Archegos, against Archegos, Hwang and a few other Archegos executives…

SUBJECT: Final Version of My Economist Piece:

Finance and economics

Brad DeLong asks what America can learn from its past bouts of inflation

In 1947 and 1951 the problem went away by itself. In 1920 the Fed tightened too much, says the economist

THE FIRST and most important thing to recognise about the macroeconomic situation in America is that Jerome Powell and his Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) should be taking victory laps. Two and a half years after the start of the financial crisis in 2007, America’s unemployment rate was kissing 10%, the Federal Reserve realised that it was out of firepower and the Obama administration had just thrown away its ability to help by promising to veto spending and tax bills that were insufficiently austere. After that moment it would take six years for America’s economy to approach full employment. The impact of deficient employment meant that output was $7trn lower in 2013 than it would have been otherwise. Additional losses stemmed from the investments not made, business models not experimented with and workers not trained during the decade of anaemic recovery.

We have avoided all that this time around. Relative to the Fed presided over by Ben Bernanke between 2006 and 2014, Mr Powell’s team are public benefactors to the residents of America to the tune of $20trn, if you consider that there are more jobs and fewer idle factories now and in the future because of their actions. We have an uptick in inflation partly because the Fed—alongside Congress and the presidency—responded far more aggressively to the pandemic-induced recession than to the global financial crisis. A world in which the economy recovers so quickly that inflation emerges is better than one in which recovery drags on painfully for years.

America has faced five bouts of inflation in the past century or so—or six, depending on whether you count the 1970s as one or two episodes. The inflation during the second world war, which was tamed by price controls, is not relevant to our situation. That leaves four (or perhaps five) historical parallels which provide lessons in how to deal with the current inflation problem.

The first is the inflation of the first world war, which was brought under control when the newly established Fed raised its discount rate from 3.75% to 4.5% between November 1917 and April 1918, and then again to 7% between October 1919 and June 2020. This triggered a short but very deep recession accompanied by substantial deflation. Milton Friedman later judged that the Fed moved too late—it should have started raising interest rates a year or more before it did—but that it moved too far when it did move.

The second is the inflation which emerged after the second world war. It peaked at 19.7% in the year to March 1947 as America’s economy reoriented itself from its wartime to its post-war structural configuration. Tank factories turned back into car factories. Resources that had been devoted to building factories and equipping them with tools were released to make all the consumer goods that had been rationed during the war. The second world war’s military-industrial complex was dismantled. Prices and wages went up in sectors where demand was high but supply constrained in order to pull resources to where they were wanted. The Fed did nothing. It was focused instead on propping up the value of all the Treasury bonds that had been issued to fight the war. Inflation averaged 8% over the following year and then went negative in 1949, when a minor recession came. Once supply had shifted to match the sectoral pattern of demand, the bottlenecks and the upward price pressure disappeared. Because few expected the inflationary trend to continue, nobody was able to demand a high wage increase or get away with a price increase, as those who paid them shrugged and said “it’s just inflation”.

The third bout came in 1951. Inflation peaked at 9.4% in the year to February that year as America geared up to fight the Korean war and, perhaps more important, as it built up its global military capabilities in the early years of the cold war. The military-industrial complex was rebuilt, and rebuilt for a nuclear and aerospace age. Again, the Fed did nothing. And the inflation wave passed. By March 1952 it was below 2%. And recession was avoided until a minor one in late 1953. Again, once supply had shifted to match the sectoral pattern of demand, the bottlenecks and the upward price pressure disappeared. Once again, because few expected the inflationary trend to continue, no one was able to ask for a high wage increase or get away with a price increase.

The fourth, or the fourth and fifth, came between 1966 and 1984. Inflation rose from 2% at the start of 1966 to 4.4% on Richard Nixon’s inauguration in January 1969. It then rose and fell throughout the 1970s before soaring to a peak of 12.8% in March 1980. The Fed dithered. Arthur Burns, its chairman from 1970 to 1978, was too interested in maintaining a strong economy while his friend and patron Nixon ran for re-election in 1972. He did not believe that Congress would let him keep interest rates high enough for long enough to cure inflation through monetary policy. It was only when Paul Volcker became chairman that interest rates were raised to a peak of 16.9% in December 1980, and were not lowered below 10% until August 1982.

Which of these is our current situation most like? In my view, the second and third bouts of inflation, in 1947 and 1951, are the right models. That is because the long-term inflation expectations implicit in the bond market are still trading at their normal “in-the-long-run-inflation-will-be-about-2.5%” range. Bond traders appear to expect a little extra inflation over the next couple of years, but after that a return to what has become considered normal. Unless workers and managers see more inflation in the future than bond traders—something that seems unlikely to me—they have no warrant for pushing for high wage increases or thinking that they can get away with price increases ahead of a continuing inflation wave. So there is considerable hope (though hope is not confidence) for a soft landing.

But there are two risks of a hard landing. One thing to fear is that the inflation episode today is like that of 1920. Back then the problem would have passed on its own, but the Fed tightened too much in response. There are no indications of overtightening yet, but then there wouldn’t be: the effects of the roughly two-percentage-point rise in both nominal and inflation-indexed ten-year Treasury rates since December 2021 will not begin to show in the real economic data until 2023.

The second risk is that this is indeed like the 1970s, and so it is imperative to scotch any expectations of an inflationary spiral before they are even formed. Turn on the news, and there is constant chatter that likens our situation to that of the 1970s, with suggestions to hedge against inflation.This may reflect the tendency of social and professional media towards clickbait, but it could nonetheless shift expectations. There is little indication so far of such a shift in the prices of long-term bonds. Possibly it is imprudent to place too much weight on this particular harbinger alone.

Most of the time I think it would be great fun to be a member of the FOMC. Not today. The risks inherent within our current situation are immense. And misjudgments caused by a failure to listen to the right signals would be devastating.

Curious your slouching take on the interview with Herman Daly in today's NYT:

"Growth is the be-all and end-all of mainstream economic and political thinking. Without a continually rising G.D.P., we’re told, we risk social instability, declining standards of living and pretty much any hope of progress. But what about the counterintuitive possibility that our current pursuit of growth, rabid as it is and causing such great ecological harm, might be incurring more costs than gains? That possibility — that prioritizing growth is ultimately a losing game — is one that the lauded economist Herman Daly..."

"And they engage in complicated symbolic interactions that have the emergent effect of distributing status and power and coordinating the seven-billion person division of labor of today’s economy."

My favourite definition of government ever. I may have to get this on a mug or something.

(As a UK civil servant this past week the complicated symbolic interactions have been *interesting*, in ways that remind you why we should all strive to be as boring as possible.)