First:

Here we see a striking difference between Paul Krugman and Larry Summers. Krugman sees models as intuition pumps—and believes strongly, very strongly, that if you cannot make a simple model of it, it is probably wrong. Summers believes that our models are, at best, filing systems (and at worst tools for misleading the unwary)—and that the right way to think about the economy is as, in some way, a two-state system, with expansion being one state and recession the other, so that you cannot halt an expansion without tipping the economy fully into recession:

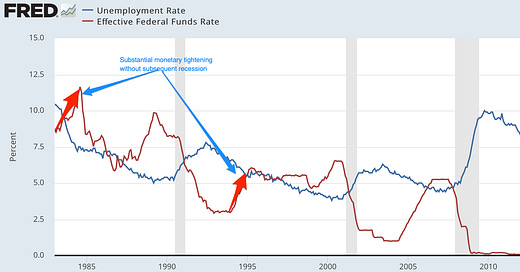

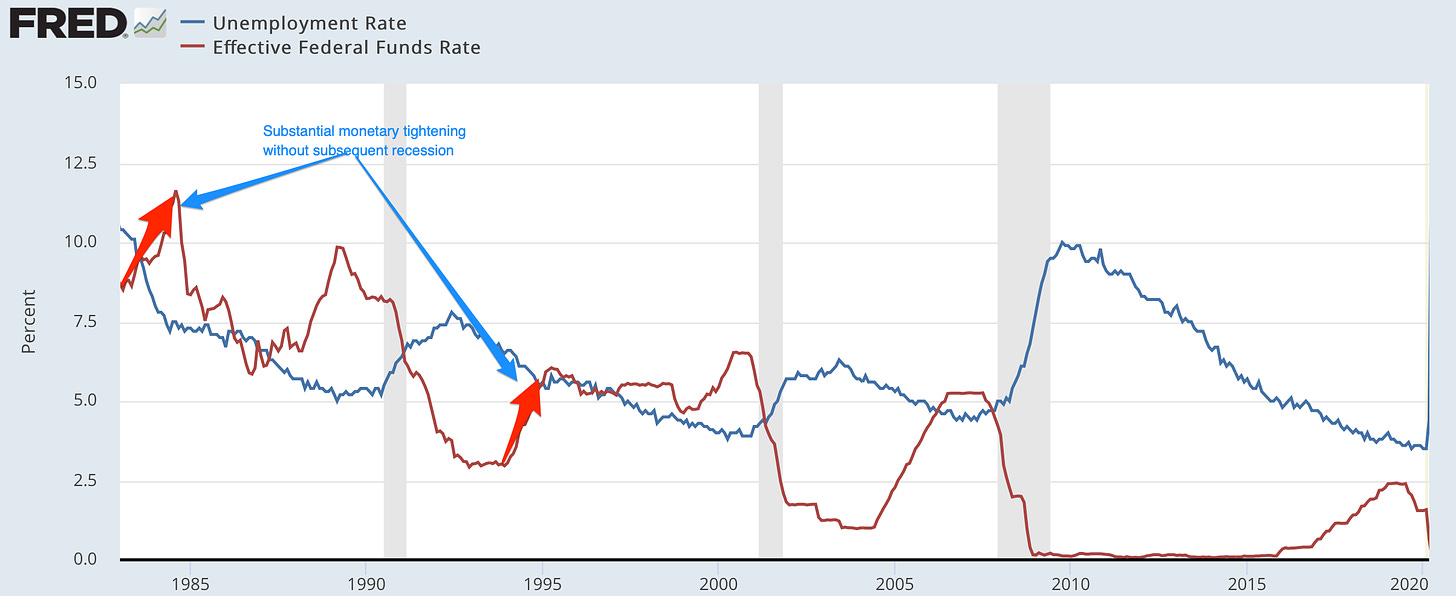

Paul Krugman: Wonking Out: Braking Bad?: ‘A more explicit critique comes from Larry Summers, who has warned that the stimulus may lead to stagflation. He appears to believe that the Fed can’t use monetary tightening to offset overheating generated by fiscal expansion without causing a nasty recession. But I have to admit to being a bit puzzled about why…. Summers[’s]… underlying macroeconomic model is pretty much the same as mine…. And that model seems to say that the Fed can indeed tap on the brakes if needed. Indeed, the Fed has done that in the past: in the 80s and again in the 90s it acted to rein in booms without causing recessions…. Claims that we can’t rely on the Fed to rein in inflation if the stimulus turns out to be too big have to rest on some departure from the workhorse model most sensible people use to think about macroeconomic policy…. Even if you’re uncomfortable with President Biden’s fiscal policies, you should be very cautious about making arguments against them that rely on novel propositions about why inflation can’t be contained. Conventional analysis says what Janet Yellen said: If the stimulus proves bigger than needed, the Fed can keep things under control. If you’re asserting otherwise, think hard about why you’re saying that…

LINK: <https://messaging-custom-newsletters.nytimes.com/template/oakv2>

My take? Of the last six tightening cycles, three have been followed by demand-shock recessions within two years of the tightening cycle’s end. I interpret this as: you gotta halt the tightening before you overdo it, and that is not the easiest thing in the world. But there is no law-like regularity there.

Snippet from a Dialogue:

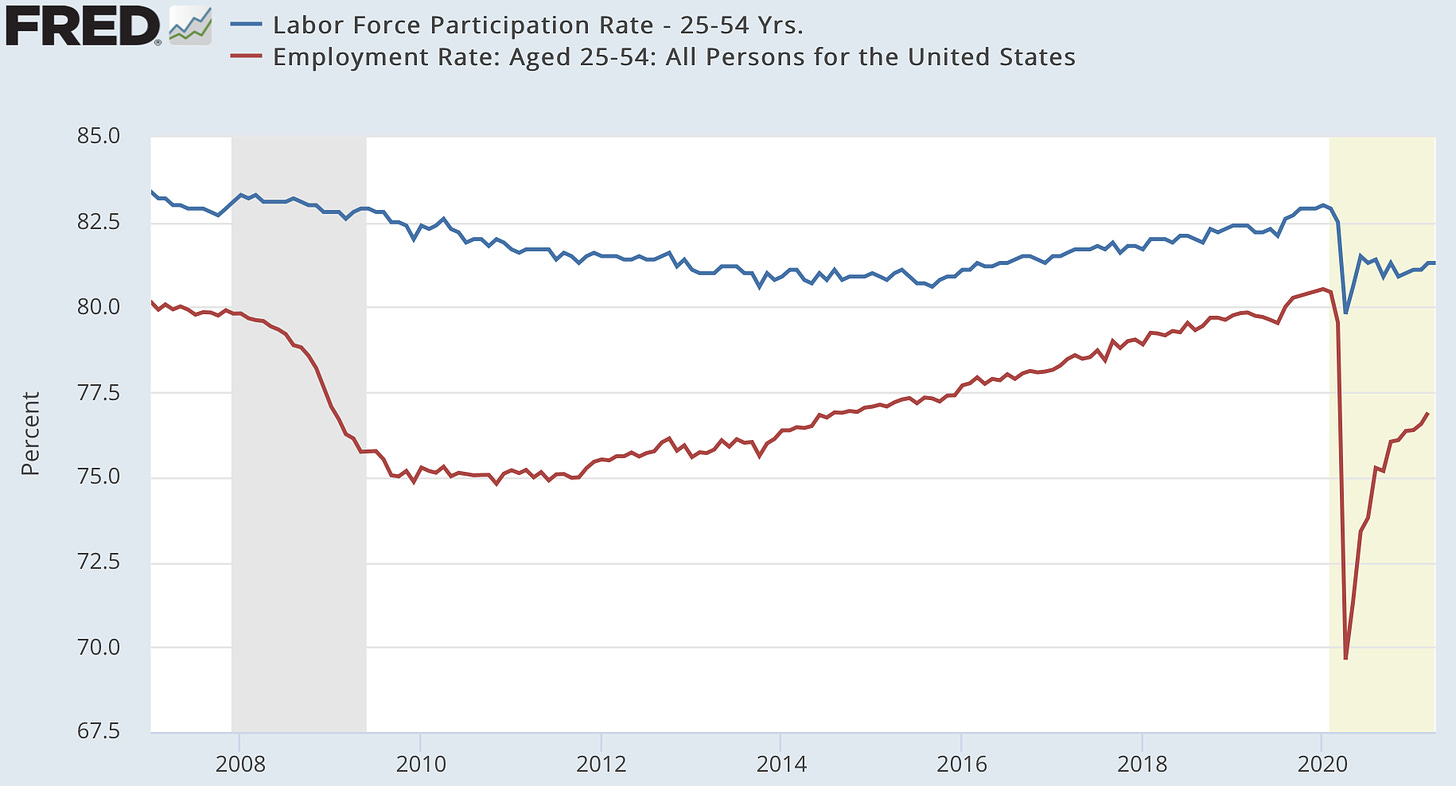

Axiothea: The gap between the labor-force participation rate for prime-age workers and the unemployment rate is still large—as large as it was in 2014. That suggests to me that our first take should be that, except for rate-of-change effects, the labor market now is about as tight as it was in 2014.

Kephalos: That the “labor shortage” crowd thinks that the unemployment rate includes a bunch of people who are really out-of-the-labor-force is something I find somewhat disturbing. Or do they not know that unemployment is still elevated?

Glaukon: The job-openings series hit an extraordinary record high at the end of March: over 8 million. I suggest that helps answer some of the questions. It certainly would not be easy to fill that many slots quickly, no matter what level of benefits people are receiving (or indeed, how quickly employers boost wages).

One Video

polyMATHY: Romanes Eunt Domus EXPLAINED:

Paragraphs:

Yes, there is a substantial amount of craziness in the froth around the “fight structural racism” movement. No: I do not think it is terribly important. Any further questions?

John Ganz: “That’s Not A Personality, Sweetie”: ‘Tema Okun’s anti-racism training materials… with a slightly different emphasis… sound like…white nationalis[m]…. They suggest only “white supremacy culture” inculcates fastidiousness, precision and a concern with logic and objectivity… white supremacist propaganda that connects “civilization” necessarily with whiteness…

LINK: <https://johnganz.substack.com/p/thats-not-a-personality-sweetie>

When Tim Duy left the open internet, the public sphere took a big loss:

Tim Duy: Fed Watch 2021–05–10: ’It strains credibility to argue that the enhanced unemployment benefits do not disincentive job search efforts. That said, I fear unemployment benefits receive outsized attention…. Financial support from tax rebates, ongoing pandemic fears, lack of access to childcare and schools, and retirements. Together, these factors point toward a fairly slow recovery of the labor supply…. There is also the fundamental issue that firing happens more quickly than hiring…. A level shift up in wages and prices does not by itself equate to a change in the underlying dynamic that would perpetuate into persistently higher inflation. We most likely will not have much sense of the persistence of inflation until the known base and reopening effects pass. That means the Fed will not want to validate any moves by market participants to pull rate hikes forward again on the basis of near-term inflation numbers…

I do think that worry about raising taxes should be postponed until interest rates have semi-normalized. But, otherwise, this is very wise indeed:

Barry Eichengreen: Will the Productivity Revolution Be Postponed?: ‘The 1918–20 influenza… came on the heels of advances… the assembly line… the superheterodyne receiver… Radio Corporation of America, the leading high-tech company… chemical processes… lowered fertilizer costs…. But… the full impact was felt only in the 1930s. Firms used downtime during the Great Depression to reorganize production, and those least capable of doing so exited…. Government invested in roads, allowing the nascent trucking industry to boost productivity in distribution. But more than a decade first had to pass…. This extended delay suggests two important lessons. First, some lag is likely…. Second, government can take steps to ensure that the acceleration commences sooner rather than later…. It would be counterproductive, obviously, to curtail infrastructure spending… or spending on early childhood education…. But the more concerned you are about a delay before faster productivity growth materializes, the more strenuously you should insist that Biden’s spending plans be financed with taxes in order to avert the overheating scenario…

“Neoconservatism” focused on the Cold War and the “traditional family”—with more than a soupçon of racism attached. “Neoliberalism” focused on economic structure and incentives. They were not, really, allied, except at moments of convenience. This is not to say that people could be both. But it is also worth noting that “neoconservatism” was a strong reaction against Nixon-Kissinger-Ford foreign policy:

Adam Tooze: Chartbook Newsletter #19: ‘In 1971 Congress passed the Comprehensive Child Development Bill…. As Walter Mondale remarked at the time: “the American people must realize that there is no answer to the unfairness of American life that does not include a massive preschool comprehensive child development program. Anything less than that is an official admission by this country that we don’t care.” Despite the fact that the Bill was passed with bipartisan support by both the House and the Senate, it was vetoed by Richard Nixon. In the explanation for his veto he warned that public child care would weaken the family and import to the United States the practices of the Soviet Union…. The alliance between neoliberalism and neoconservatism… linking a defense of a restored “traditional” family to a reassertion of the market order and an overturning of the New Deal compromise on welfare…

LINK: <https://adamtooze.substack.com/p/chartbook-newsletter-19>

Longer:

Furman and Powell are talking sense, both about the current situation and about the uncertainties:

Jason Furman & Wilson Powell: The US Labor Market Is Running Hot… or Not?: ‘The United States added 266,000 jobs in April while the unemployment rate rose slightly to 6.1 percent with the realistic unemployment rate, which adjusts for misclassification and the unusual decline in labor force participation, falling to 7.6 percent… still 10 million jobs short of its pre-pandemic trend in April with the employment rate down 3.2 percentage points since February 2020….

The labor market has still been behaving as if there was relatively little or even no slack left: Openings were at record levels, quits were near record levels in February, composition-adjusted wages were growing at the same pace they did in the relatively tight 2019 labor market with the largest wage gains for the lowest-wage workers, wages not adjusted for changing composition rose 0.7 percent in April, and average weekly hours remain very high…. With so many conflicting signals as the labor market changes rapidly with demand and supply returning to different degrees in different sectors, it is hard to make a confident assessment….

The labor market has a ways to go before it is healed. The question is what form this adjustment will take and what the risks are…. Looking forward there are good reasons to expect large increases in both demand for labor and supply of labor…. One downside scenario is overheating…. A second downside scenario is an incomplete jobs recovery…. The third downside scenario is that the virus itself takes a turn for the worse… The most likely outcome may be the Goldilocks scenario. In this scenario both demand and supply return. Patches of mismatch in timing and sectors would lead to noticeable shortages and price and wage increases in some areas, especially over the spring and summer as high demand is temporarily unable to fully be satisfied by available labor. However, these mismatches work themselves out with only transitory increases in the level of prices and no persistent changes in inflation or inflation expectations.…

LINK: <https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/us-labor-market-running-hotor-not>

Hoisted from the Archives:

When I first saw the Solow growth model in one of my first economics classes, I raised my hand, and I asked: Why is it assumed that gross savings is a constant share of gross income—that is, income plus depreciation. Isn’t that the same as assuming that people are too stupid to calculate deprecation? Shouldn’t the right assumption be that net savings is a constant share of netincome?

The teacher then filibustered.

I eventually asked Bob Solow this question. He said—accurately—that in his original paper it had indeed been net savings and net output (Cf. Solow (1956): A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth <http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Solow1956.pdf>, in which there is no deprecation—the key parameters are “the savings rate, the capital-output ratio, the rate of increase of the labor force). When asked why he had shifted to gross savings as a constant share of gross income, he shrugged his shoulders and said ”referees".

Indeed.

Unless you assume that people cannot calculate depreciation, the first optimizing model for a representative agent one would naturally write down has net savings a share of net income, with the share depending on expected real risk and return.

I have always taken it to be a sign of the low quality of so much of the criticism of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century that professors claim Piketty’s assumption that net savings is a constant share of net income is a gotcha—is (a) some kind of an analytical mistake, because it implies an ever-growing share of depreciation in gross output in a world where the economic growth rate of the economy n+g = 0 is zero; and (b) that it is a hugely consequential mistake. IMHO, you can only maintain it is consequential if you lack familiarity with the NIPA, and its depreciation rates—if the “illustrative” deprecation rate you keep in year head is 10% of income-earning wealth a year, and so think that in the U.S. today annual deprecation allowances are more like $12 trillion/year (60% of GDP, 12% of the income-earning wealth stock) than like $4 trillion/year (15% of GDP; 4% of the income-earning wealth stock).

This, seven years ago, really did not go well at all.

You woulda thunk that people wouldn’t double down after it was pointed out to them that (a) far from being fundamental and canonical, depreciation was not even in the Solow (1956) that is cited ten times a day, and (b) that something is badly wrong with your thinking if the numbers you have in your head say that depreciation—capital consumption allowances—are 60% of U.S. GDP. But no! Far from it!:

Per Krusell & Tony Smith: Is Piketty’s “Second Law of Capitalism” Fundamental?‘[Piketty’s] argument about the behavior of k/y as growth slows, in its disarming simplicity, does not fully resonate with those of us who have studied basic growth theory… or… optimizing growth…. Did we miss something important, even fundamental, that has been right in front of us all along? Those of you with standard modern training… have probably already noticed the difference between Piketty’s equation and the textbook version…. The capital-to-income ratio is not s/g but rather s/(g+δ), where δ is the rate at which capital depreciates when growth falls all the way to zero, the denominator would not go to zero but instead would go from, say 0.12—with g around 0.02 and δ=0.1 as reasonable estimates—to 0.1…’

LINK: <https://web.archive.org/web/20150529012920/http://www.econ.yale.edu/smith/piketty1.pdf>

James Hamilton: Educating Brad DeLong: ‘Reader Salim points out that I was misinterpreting Piketty’s use of a 10% figure in his book’s calculations of depreciation. Piketty uses 10% for depreciation as a percent of GDP, not as a percent of capital as my original post suggested. In order not to mislead, I have deleted the inaccurate paragraphs that were included in the first version of this post…’

LINK: <https://econbrowser.com/archives/2014/06/educating-brad-delong>

Per Krusell: ‘We consider the subject of Piketty’s work really important…. This… however, is no excuse for using inadequate methodology or misleading arguments…. We provided an example calculation where we assigned values to parameters—among them the rate of depreciation. DeLong’s main point is that the rate we are using is too high…. It is, however, disappointing that DeLong’s main point is a detail in an example aimed mainly, it seems, at discrediting us by making us look like incompetent macroeconomists…. We have read Piketty’s book and papers, and so we of course know that Piketty knows; our note is thus not written for him but instead, as we say in the introduction to the paper, for all of those who might be puzzled by the striking result that he derives from his non-standard theory…’

LINK: <https://ekonomistas.se/2014/05/29/krusell-och-smith-darfor-koper-vi-inte-pikettys-prognos/>

Brad DeLong: Brad DeLong brad.delong@gmail.com Wed, Jun 4, 2014, 2:34 PM: Please tell me if I am crazy….

Piketty’s estimates of the capital/annual income ratio in France and Britain in 1910 are both equal to 7. At an annual depreciation rate of 10% and with a net-of-depreciation concept of income, that means that 41.176% of gross income is devoted to replacing worn-out capital.

That can’t be what anybody thinks, can it? For Piketty’s purposes, a 10%/year rate of deprecation cannot be a sensible choice can it? Krusell and Smith’s choice of a 10%/year depreciation rate to calibrate Piketty’s model makes no sense, does it?

Do people really think that in 1900 41.176% of French gross output was taken up by capital consumption?

Physical capital depreciation rates in growth (as opposed to business-cycle) models are more like 5% than 10%, aren’t they?

And to the extend that a substantial chunk of your capital stock takes the form of high-productivity land–which doesn’t depreciate–5% is too large, isn’t it?

Am I crazy?

Sincerely Yours,

Brad DeLong

Thomas Piketty: ’Hello, we do provide long run series on capital depreciation in our “Capital is back” paper with Gabriel (see <http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/capitalisback>, appendix country tables US.8, JP.8, etc.). The series are imperfect and incomplete, but they show that in pretty much every country capital depreciation has risen from 5–8% of GDP in the 19th century and early 20th century to 10–13% of GDP in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, i.e. from about 1% of capital stock to about 2%…

Best,

Thomas’

Dear Professors Krusell, Smith, Hamilton:

This is not going well at all….

At Piketty’s reported wealth-to-annual-income ratio for France in 1910 of 700%, a 10%/year depreciation rate implies that capital consumption is 70% of net income—41% of gross output.

Thus I have seven questions:

Do you believe that capital consumption was 70% of net income/41% of gross output in France in 1910?

If you do so believe, how is such a remarkably high share–40% of all economic activity in France devoted to replacing and repairing capital as it wears out and becomes obsolete–consistent with even a surface acquaintance of the structure of the French economy in 1910?

If you do so believe, can you point me to any sources to back up such a huge wedge between gross output and net income, especially since Piketty and Zucman’s estimates of the wedge between gross output and net income tend to be in the 5–8% range for the nineteenth century and the 10–13% range for today?

If not, why did you assume a deprecation rate that would lead to such an absurd picture of the structure of the French economy as of 1910?

Have you thought about what the appropriate depreciation rate should be?

How responsive do you believe the gross savings rate is to shifts in the wealth-to-annual-income ratio W/Y?

How much trust do you have in life-cycle models of the impact of wealth on consumption in an environment of extreme inequality, like that of the Belle Époque, or (perhaps) the mid–21st century?

Sincerely yours,

Brad DeLong

Per Krusell: ‘I really did not appreciate the tone of your blogs on this matter. Because of the importance of the topic covered in the book—it is one I care greatly about—and because so many people are interested in it, I nevertheless decided it made sense to write a short answer together with Tony. But, in general, on the few occasions when I write columns or guest blogs, I have a rule not to respond to people who do not maintain a minimum of politeness in their questions/comments. Without this rule, it would simply be too emotionally draining for me, and simply not worth it. Since the tone of the email you just sent is still rather unpleasant, with rhetorical questions and a clear unwillingness to engage in our arguments, I will henceforth not respond…’

And so let me give the last word to Thomas Piketty:

Thomas Piketty: ’Thomas Piketty: ‘There are huge variations across industries and across assets, and depreciation rates could be a lot higher in some sectors. Same thing for capital intensity. The prolemb with taking away the housing sector (a particularly capital intensive sector) from aggregate capital stock is that once you start to do that it’s not clear where to stop (e.g. energy is another capital intensive sector). So we prefer to start from an aggregate macro perspective (including housing), and here it is clear that 10% or 5% depreciation rates do not make sense…’

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)