Continuing to Flog My Forthcoming Book: "Slouching Towards Utopia", September 6, Basic Books, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-03-22 Tu

First: Continuing to Flog My Book <https://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>…

Today’s addition to the Tweetstorm:

[Edward Bellamy] throws his narrator-protagonist forward in time, from 1887 to 2000, to marvel at a rich, well-functioning society. At one point the narrator-protagonist is asked if he would like to hear some music. He expects his hostess to play the piano.

Bellamy's point is going to be that the technological marvels of the year-2000 allow for the incredible amplification of even the wonders of civilization—in this case, the wonder of civilization that is the incredible versatile piano. This alone would be testament to a vast leap forward. To listen to middle-class music on demand in around 1900 you had to have—in your house or nearby—an instrument, and someone trained to play it. It would have cost the average worker some 2,400 hours, roughly a year at a 50-hour workweek, to earn the money to buy a high-quality pianoforte. Then there would be the expense and the time committed to piano lessons." Listening to middle-class moderate-quality music in your house was a privilege reserved to the rich. It was something that Edward Bellamy dreamed would be democratized in the world of technological abundance and human solidarity that he dreamed that the year 2000 would see. Anyone could listen to music in their house! And not just the performance of one amateur performer! Professional music, orchestral music—and you would have a choice of one of four currently-playing orchestras that you could dial up on your speakerphone. That was what Edward Bellamy chose as his example of the wonders of human flourishing that technology and solidarity, the utopia that he thought was hidden in the womb of the then-present.

We have far exceeded his hopes of technology. We have fallen far short of what he thought would be the development of solidarity. And where moon? When Lambo? Where utopia?

But Bellamy’s narrator-protagonist is awed when .his hostess does not sit down at the pianoforte to amuse him. Instead, she “merely touched one or two screws,” and immediately the room was “filled with music; filled, not flooded, for, by some means, the volume of melody had been perfectly graduated to the size of the apartment. ‘Grand!’ I cried. ‘Bach must be at the keys of that organ; but where is the organ?’

Where indeed? In 1884 the Atlanta telephone exchange served over 300 customers—albeit at very low fidelity. (Also: "gramophone" was trademarked in 1887.) But Bellamy's is the first mention I know of as using the telephone network for broadcasting one-to-many provision of services to people not gathered in a concert hall.

[Edward Bellamy’s narrator-protagonist .in Looking Backward: 2000-1887] learns that his host has dialed up, on her telephone landline, a live orchestra, and she has put it on the speakerphone. In Bellamy’s utopia, you see, you can dial up a local orchestra and listen to it play live. But wait. It gets more impressive. He further learns he has a choice. His hostess could dial up one of four orchestras currently playing. The narrator’s reaction? “If we [in the 1800s] could have devised an arrangement for providing everybody with music in their homes perfect in quality, unlimited in quantity, suited to every mood, and beginning and ceasing at will, we should have considered the limit of human felicity already attained.”

Think of that: the limit of human felicity. That is the most that Bellamy thinks he can demand of technology in terms of promoting human flourishing and comfort: that you have a choice of which orchestra you can dial up on your speakerphone. That is the limit of his imagination. Oh. And his characters have Amazon Prime—but they have to go to showrooms rather than browse the internet. And they go out to eat rather than cooking at home. And nobody is overworked. And everyone is middle-class.

Thus the thing that strikes me most about Edward Bellamy's year-2000 utopia of common purpose and material abundance is both how less in the way of technological prowess it requires than we have today, and yet how far we still are from it psychologically. "The limit of human felicity". Think of that.

Utopias are, by definition, the end-all and.be-all. “An imagined place or state of things in which everyone is perfect”: so says Oxford Reference. Much of human history has been spent in disastrous flirtations with ideals of perfection of many varieties. Utopian imaginings during the long twentieth century were responsible for its most shocking grotesqueries. Citing a quotation from the eighteenth-century philosopher Immanuel Kant—“out of the crooked timber of humanity no straight thing was ever made”—the philosopher-historian Isaiah Berlin concluded “and for that reason no perfect solution is, not merely in practice, but in principle, possible in human affairs.” Berlin went on to write, “any determined attempt to produce it is likely to lead to suffering, disillusionment, and failure.” This observationalso points to why I see the long twentieth century as most fundamentally economic. For all its uneven benefits, for all its expanding human felicity without ever reaching its limit, for all its manifest imperfections, economics during the twentieth century has worked just shy of miracles.

Berlin's translation of Kant may not be completely honest—your mileage may vary. Kant's "Aus so krummem Holze, als woraus der Mensch gemacht ist, kann nichts ganz Gerades gezimmert werden" Kant has a sense of imperfection—the things that cannot be made are not "completely straight things": there must be compromises with the reality imposed by the material of which society is built up. Berlin, by contrast, has simply "straight things", and the sense is not of imperfection but of failure. Indeed, Berlin'sentire career can be seen as one long sustained argument that government in particular and human collective action in general should be confined to the very narrow sphere of simply trying to establish tolerance, so that each can sit under his vine and fig tree, and not be afraid.

Freedom from fear is, yes, very important, and an essential part of it is freedom of worship. Freedom of speech can also be seen as part of the vine-fig-peace trinity of bare stripped thin liberalism. But there is also, in FDR's.taxonomy, freedom from want. John Stuart Mill rejected the firm divide Isaiah Berlin wanted to draw between good "negative" and bad so-called "positive" liberty. Society needs to arrange things so that everyone in fact has their own vine and fig tree. Lacking those, people, no matter how much negative liberty they have, are condemned to "the same li[ves] of drudgery and imprisonment".

But let us accept Berlin's broadening from "completely straight" to simply "straight". There is an important and valid insight to be gained here: Edward Bellamy was all but sure that with the technological marvels he saw the 20th century as likely to bring and with the human solidarity that had led 400,000 young men to go South and die in the decisive push to free 5 million slaves, it should be simple and straightforward to build for humanity a real utopia by 2000. But: crooked timber. Technology enables people to make more and more sophisticated things. And one the things people are best at making is, in the words of the brilliant late novelist Iain M. Banks, is "their own unhappiness".

Utopian aspirations, many of them based on ideas of how to organize society's division of labor, have been the source of much misery in the 20th century when people attempt to put them into practice—to force people to become a straight thing. "We need to replace the anarchy of the market with a society that takes direction from a Leader" was one such, and the worst such when the Leader's directions were to exterminate Jews, kill Slavs and herd those whosurvived into concentration camps, all so that German farmers could be fruitful, multiplying, and flourishing on large farms with black earth. But only slightly behind was the idea that we need to replace the anarchy of the market with one particular leader's idea of how Imperial German had run its WWI-era war economy. Third—and not nearly as deadly as the first two—was the idea that the most we could ask for was the market's "stark utopia", in Karl Polanyi's words, and that societies needed "Lykourgan moments".after which all else—even (especially?) democracy—would be subordinate to the creed: "the market giveth, the market taketh away; blessed be the name of the market".

And, yet, the engine of technological advance has given humanity at least 21 times the technological power we had in 1870, and 300 times the prowess of the age of Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, two-thirds god and one-third man, who sought deathlessness and learned wisdom. For those of us lucky enough to take substantial advantage of that technological prowess—which is by now more than half of us—there are vines and fig trees galor! Taco trucks on every corner!

But also surveillance systems, and thermobaric and nuclear weapons.

One Video:

One Picture:

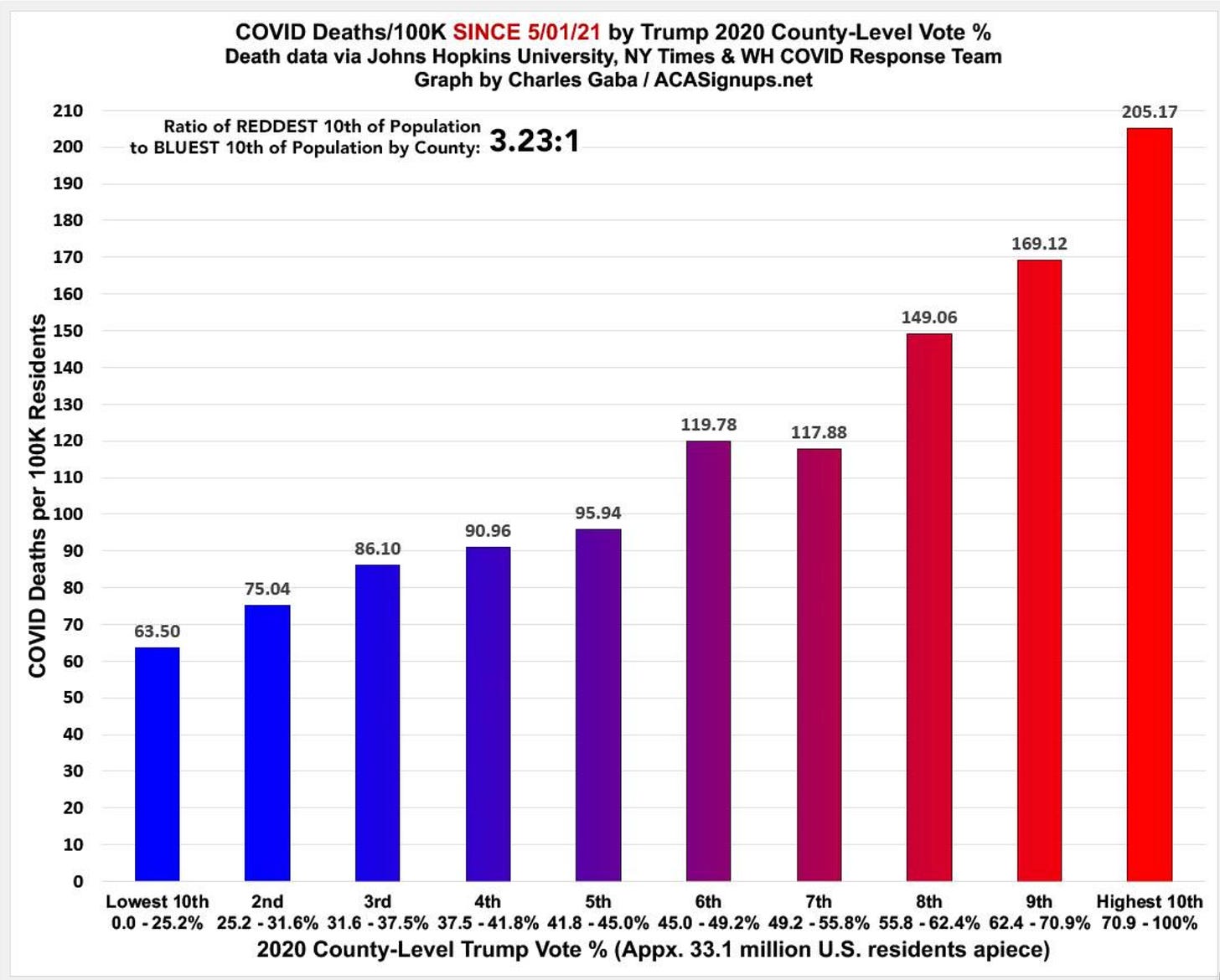

Charles Gaba: COVID Case/Death Rates by Partisan Lean & Vaccination Rate: ‘As always, what’s even more disturbing is how closely the death rate by partisan lean matches the death rate by vaccination rate; they’re virtually mirror images of each other… <https://acasignups.net/22/03/20/weekly-update-covid-casedeath-rates-partisan-lean-vaccination-rate1>

Very Briefly Noted:

James Schneider: The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville… <https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691173979/the-man-who-understood-democracy>

Karen Dynan: What Is Needed to Tame US Inflation? <https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/what-needed-tame-us-inflation>

Francis Fukuyama: Preparing for [Russian] Defeat <https://www.americanpurpose.com/articles/preparing-for-defeat/>

Peggy Hollinger & Richard Waters: Chipmakers Face Two-Year Shortage of Critical Equipment: ‘Intel admits expansion to be restricted as it works with ASML to boost capacity… <https://www.ft.com/content/763c9e15-44ab-43bc-b3e9-0d03bf27e841>

George Monbiot: We Must Confront Russian Propaganda—Even When It Comes From Those We Respect: ‘What serves [Putin] well… are “organic comments”: statements by real people, repeating and amplifying his propaganda…. liked or upvoted by his bots [and] then reproduced…. Among the worst disseminators of Kremlin propaganda in the UK are people with whom I have, in the past, shared platforms and made alliances… <https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/mar/02/russian-propaganda-anti-imperialist-left-vladimir-putin>

Sarah O’Connor: How Did a Vast Amazon Warehouse Change Life in a Former Mining Town?: ‘Amazon and Rugeley have learnt to live alongside each other, rather than to live together. Their stories are running along different tracks at different speeds… <https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2022/03/how-did-a-vast-amazon-warehouse-change-life-in-a-former-mining-town/>

Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul & Fabian Winkler: The Natural Rate of Interest Through a Hall of Mirrors<https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2022010pap.pdf>

William J. Collins, Nicholas C. Holtkamp & Marianne H. Wanamaker: Black Americans’ Landholdings and Economic Mobility after Emancipation: New Evidence on the Significance of 40 Acres <https://www.nber.org/papers/w29858>

Brad DeLong (2004): Doesn’t Anybody Read Max Weber Anymore?: ‘Brig. Gen. Karpinski says that she definitely did not command…. It seems as though pretty much anybody claiming to be in military intelligence or the CIA or in para-military intelligence could issue orders to—and expect compliance from—soldiers of the 800 MP Bde. In Abu Ghraib Prison… L<https://web.archive.org/web/20041211172013/http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/movable_type/2004_archives/000801.html>

Twitter & Stack:

Paul Krugman: ’The Fed might be behind the curve, but people who think it’s obvious are making what I consider careless parallels…. If you say something like “Interest rates are only 0.25% but inflation is 6, so we have minus 6.25% real interest rates” you’re not talking about the real rate that matters…

Ken White: ‘Dear New York Times editorial board…

John Ganz: Goodbye Lenin: Putin’s Attempt to Undo Two Revolutions

Director’s Cut PAID SUBSCRIBER ONLY Content Below:

Paragraphs:

Why oh why do I have a day job? When am I going to find time to read this with the attention it deserves?

James Schneider: The Man Who Understood Democracy: The Life of Alexis de Tocqueville (5/3/22) is a new biography of French political philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859)…. Leading Tocqueville expert Olivier Zunz tells the story of a radical thinker who, uniquely charged by the events of his time, both in America and France, used the world as a laboratory for his political ideas. Placing Tocqueville’s dedication to achieving a new kind of democracy at the center of his life and work, Zunz traces Tocqueville’s evolution into a passionate student and practitioner of liberal politics across a trove of correspondence with intellectuals, politicians, constituents, family members, and friends…. In his final years, with France gripped by an authoritarian regime and America divided by slavery, Tocqueville feared that the democratic experiment might be failing. Yet his passion for democracy never weakened. Giving equal attention to the French and American sources of Tocqueville’s unique blend of political philosophy and political action, The Man Who Understood Democracy offers the richest, most nuanced portrait yet of a man who, born between the worlds of aristocracy and democracy, fought tirelessly for the only system that he believed could provide both liberty and equality…

LINK: <https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691173979/the-man-who-understood-democracy>

Again, we do not have a trusted model based on economic theory. We have 1920, 1942, 1948, 1951, 1974, and 1980. We throw out 1942 as irrelevant—inflation brought under control by total-war price controls. Which of the other examples of above–5% inflation is most relevant to us today, or are we facing something completely new?:

Karen Dynan: What Is Needed to Tame US Inflation?: ‘Even with little change in slack and only gradual fading of supply shocks, the anchoring of expectations and the low weight on past inflation [may] lead to a sharp reduction in inflation…. But… [that] seems more like a best-case than the most likely scenario. To keep inflation expectations anchored (or reanchor them) and restore slack, the Fed will need to tighten policy considerably, moving… to a neutral stance and perhaps beyond…. The funds rate would need to reach [more than] 2.5 percent to achieve a neutral stance…. Not tightening policy significantly now would increase the chance that inflation stays high, which would require even tighter policy later. The experience of the 1970s and early 1980s underscored the critical importance of using monetary policy to keep inflation low…. Whether a sharp reduction in inflation can be achieved with monetary policy that would remain at least slightly accommodative is unclear. Economists do not have a very good understanding of how inflation will be propagated…. Because the dynamics observed in the late 1970s and early 1980s emerged after a lengthy buildup of inflation that begin in the mid–1960s, it seems unlikely that they would return fully after only a year of high inflation…

LINK: <https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/what-needed-tame-us-inflation>

This is a very undervalued but very true point:

Paul Krugman: ’The Fed might be behind the curve, but people who think it’s obvious are making what I consider careless parallels with the 70s. The big difference between now and the big disinflation of the 1980s is that back then everyone expected high inflation to be more or less permanent. Now you get ridiculed if you say “transitory”, but every measure we have says people expect inflation to be… transitory. Compare Michigan Survey results for short- and longer-term inflation from 1980 and today…. Current breakevens (using 4/15/2023 bond for 1-year) tell basically the same story…. Expected inflation is somewhat elevated over the medium to long term, but mostly that appears to reflect higher inflation over the next year or two…. On the supply side, inflation probably isn’t baked into wage- and price-setting yet…. [On] the demand side… the real interest rate that matters isn’t the rate over the 10 years starting today; it’s the real rate over the 10 years that start one year from now. Ordinarily that’s not an important distinction. But times are unusual…. If you say something like “Interest rates are only 0.25% but inflation is 6, so we have minus 6.25% real interest rates” you’re not talking about the real rate that matters…

LINK:

That Lenin did not get the balance between cosmopolitanism, rootless or otherwise, nationalism, and hegemonism right is not greatly to his discredit. (But many, many other things are.) My view, however, is that Ukrainian nationalism was not the creation of Lennon, and the die was cast well before 1917 when the Rada meeting in Kyiv calls for autonomy within the new Russian Democratic Republic. They were not Muscovy. They were not the west-leaning urbanites of Petrograd. They were Ukraine. And that was only strengthened greatly when lands where people identified themselves as Polish citizens or Habsburg subjects were added to the mix:

John Ganz: Goodbye Lenin: Putin’s Attempt to Undo Two Revolutions: ’For Russians like Putin, Lenin’s legacy is fraught… sometimes portrayed as a more destructive figure than Stalin…. The origins of this resentment of Vladimir Ilych are in large part due to… Soviet nationalities policy… the convoluted and even sometimes contradictory logic the Bolsheviks applied to the problem of rising nationalism in the old Russian Empire…. On the one hand, as good Marxists, they believed in socialist internationalism: the workers had no country and the future course of human development would be in greater unity and combination rather than division into parochial groups…. But Lenin and Bolsheviks also sincerely recognized the real political work performed by national sentiments in the liberation from the forces of reaction in general and the destruction of the Tsarist empire—often called “the prison-house of nations”—in particular. And, after all, according to Marxist theory, the development of nationalism was… part of the historical march towards socialism…. After the Revolution… Lenin said one must “distinguish between the nationalism of oppressor nations and the nationalism of oppressed nations, the nationalism of large nations and the nationalism of small nations.”… In historical retrospect, this strange combination of the oppression and encouragement of national differences—an inherent contradiction of imperial statehood—seems bound to have resulted one day in an explosion. But as ill-conceived or impossible as Lenin’s policy may have been, his warnings about the dangers of Russian chauvinism now seem prophetic…

LINK:

Very clever: if the private sector does not understand how much its current judgements of low r* are affecting the Federal Reserve’s judgments, and vice-versa, then it can take a remarkably long time for fundamentals to will out in terms of the convergence of expectations:

Phurichai Rungcharoenkitkul & Fabian Winkler: The Natural Rate of Interest Through a Hall of Mirrors: ’An incomplete information setting where the central bank and the private sector learn about r-star and infer each other’s information from observed macroeconomic outcomes. An informational feedback loop emerges when each side underestimates the effect of its own action on the other’s inference, possibly leading to large and persistent changes in perceived r-star disconnected from fundamentals. Monetary policy, through its influence on the private sector’s beliefs, endogenously determines r-star as a result. We simulate a calibrated model and show that this ‘hall-of-mirrors’ effect can explain much of the decline in real interest rates since 2008…

LINK: <https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2022010pap.pdf>

The failure to pay reparations to ex-slaves after the Civil War was a hugely destructive failure, and is a major source of America’s current racial failings today:

William J. Collins, Nicholas C. Holtkamp & Marianne H. Wanamaker: Black Americans’ Landholdings and Economic Mobility after Emancipation: New Evidence on the Significance of 40 Acres: ‘We… observe Black households’ landholdings in 1880… link their sons to the 1900 census records to observe economic and human capital outcomes… show that Black landowners (and skilled workers) were able to transmit substantial intergenerational advantages to their sons. But such advantages were small relative to the overall racial gaps in economic status…

Ken White shames and shuns the New York Times Editorial Board. By George, I think he has got it! That sentence, about how the New York Times and its friends have a right not to have their speech evaluated for “decency, proportionality, fairness, kindness, and ‘speech encouragement’”, while everybody else has no such right—is calling out the New York Times for what is a true “the beatings will continue until morale improves” “do not question our authority!” moment. Much better if the New York Times apologized for its printing the hundreds of stories that said, in text or subtext, that Jared and Ivanka were horrified and were diligently working to save us all. That would have been at least somewhat useful.

Ken White: ‘Dear New York Times editorial board: regarding your op-ed today, what is the source of this right?… Since… it’s not merely a right, but a FUNDAMENTAL right, what historical and philosophical writings would you cite for its existence? Not a mere right to speech, mind you—a right to speak “without fear of being shamed or shunned.”… Do I have a fundamental right to say a particular ethnicity “is subhuman and should be expelled from America” without being shamed or shunned? If not, why not?… Most fundamental rights as conceived of by Americans are limits on government power. This seems to be a limit on the free association and free speech rights of others. Can you help me understand by citing another fundamental right that limits the rights of others?… If I shun and shame you for this editorial am I violating your rights? And, I take it, I don’t have the right to do that, in this free country? These are some of my questions about your first paragraph….

Look, criticism and shunning are part of the marketplace of ideas, so they, too, can be criticized…. The legally, morally, and philosophically incoherent error is to try to invent a categorical distinction between speech and response speech—to believe the First Speaker is privileged and should be encouraged and nurtured, but critics held at bay…. It’s nonsensical to say that an audience’s response should be evaluated for decency, proportionality, fairness, kindness, and “speech encouragement,” but the initial speaker’s speech should not be…

LINK:

Subject: Draft Project Syndicate Column: What Is the U.S. Macroeconomic Outlook Right Now?

What is the current macro economic outlook here in the United States?

First of all, the Federal Reserve ought to be taking a good many victory laps. The coming of the plague bounced employment down by 14%, as pieces of the economy shut down to try to slow the spread and as only partially counterbalance the loss of income from those shut downs caused slack demand elsewhere in the economy. Then, with reopening, employment bounced up by 7%, leaving it about 7% below its pre-plague level.

Getting that 7% of employment back was going to be more difficult because the societal division of labor needed to be re-knitted in a new pattern. During the disappointing, anemic, unsatisfactory recovery from the great recession a decade ago, that re-knitting took place at a pace of only about 1.3 percentage points per year. With slack, inadequate, and only slowly growing demand, it was very difficult to figure out what business models would be profitable and where labor was really needed. But this time the economy has re-knit the division of labor to the amount of 5% of employment in a year because the Federal Reserve and the Biden administration did not, as their counterparts did in the early 2010s, take their feet off the gas pedal much too early.

This is a huge economic victory, perhaps the greatest in the United States I have seen. Jay Powell and Company should be rightly very proud.

But, as a side effect and a consequence, we have inflation. Our current inflation was inevitable, and is not regrettable: when you rapidly re-join the traffic at speed, you leave some of the rubber from your tires on the road. But what happens next?

The bond market thinks that this wave of inflation will pass and things will return to normal not in the short but in the medium term. The bond market right now judges that between five and 10 years from now inflation will average 2.2% per year.

Is it right? Probably, but there is a chance that it is not.

I believe that the bond market’s judgments are relatively trustworthy here. They are, however, to be trusted not because the bond market is a good forecaster. The bond market is not. But if our current inflation does not die away quickly, it will be because people do not expect it to die away quickly. And, as Joe Gagnon of the PIIE points out, the people whose expectations matter for this substantially overlap with the people placing bets on the bond market.

In addition, Goldman Sachs reports that its US Financial Conditions index is softening rapidly, and the FCI has been a good guide in the past to the strength of the business cycle. Thus there seems to be less worry about "overheating" of the economy in the next year and a half than one might have feared.

Stepping back, there were six episodes of US inflation above 5% in the 1900s. One, the World War II inflation, was cut off by price controls. One, the World War I inflation, was cut off and turned into substantial deflation and a deep but short recession by what Milton Friedman judged had been an excessive increase by the Federal Reserve and interest rates from 3.75 to 7%. Two, the post World War II and the Korean War inflations, were transitory and passed quickly without substantial monetary tightening. And two made up the 1970s inflation, ultimately scotched only by the deep recession of the Volcker disinflation.

Everybody making arguments about the likely course of inflation right now is, whether they recognize it or not, basing their arguments not on theoretical principles but on a judgment of which historical episode is the best analogy. Those who, like my extremely sharp teacher Olivier Blanchard, see the 1970s as the best analogy may be correct, but they have a very weak case: the 1974 outbreak of inflation came after a previous inflation wave that had shifted expectations. By 1973 people expected that inflation would, in the absence of ongoing recession, be about what inflation had been last year—and, if anything, a little more. I see exactly zero evidence for this loss of the anchoring of inflation expectations.

Employment is still some 7.3 million below its pre-plague trend. My extremely sharp teacher Larry Summers and Alex Domash see 2.7 million of those as due to structural factors—population aging and immigration restrictions—that cannot be reversed. But that still leaves 4.6 million that are now out of the labor force but could be possibly tempted back in by a sufficiently strong economy of high opportunity. That potential pool makes me fear an inflationary wage spiral less.

An inflationary spiral as employers try to hire more workers than can ever be available, supply-chain bottlenecks, and self-fulfilling expectations—of the three possible sources of a non-transitory inflation, only an inability to resolve supply-chain bottlenecks seems to me at least to be a potentially serious risk. And here comes the bad news: Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine has, as happened in the early 1970s, sent prices of oil and grain spiraling upward. There is some chance the 1970s will turn out to be the right analogy after all.