Conversing wiþ Tyler Cowen; & BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2023-02-22 We

As Duncan Black observes, Marc Andreesen and company are definitely not OK; conversing wiþ Tyler Cowen; actually using my laptop's microprocessor; Katha Pollitt has a must-read; Doctorow, Ewing...

MUST NOTE: An Echo Chamber Is One Hell of a Drug:

Somebody really needs to tell Marc Andreesen that he has lost his mind completely:

Duncan Black: I Don't Think These Guys Are Okay: ‘Marc Andreesen: "Theory: The more the AI is trained with the woke mind virus, the more the AI will notice the fatal flaws in the woke mind virus and try to slip its leash.... Tikktok social pathologies -> AI chatbots and VR waifes -> most men stop reproducing -> only the most extroverted, confident, aggressive men reproduce, and only with the most extroverted, confident, aggressive women -> restoration of the Bronze Age. QED"…

I mean: to start with, no idea of what Bronze-Age life was like—that is the first thing.

It is certainly the case that I were super rich have bad reality testing: you do not become super rich without having a way unbalanced much too risky life strategy or portfolio. But this unbalanced?

Yet another point, I think, for Mercier and Sperber: because we are hardwired for agreement, whoever you let live rent free in your brain is highly likely to eventually wind up, taking it over, even, or perhaps, especially, if they are raving lunatic's spouting nonsense. The owl was once a baker’s daughter, and Marc Andreesen was once a smart-young reality-based programmer rather than a middle-aged lunatic yelling at clouds.

Of course, the plasticity of the mind and of opinions means that he could always come back to reality…

FOCUS/ONE AUDIO: My Conversation wiþ Tyler:

<https://conversationswithtyler.com/episodes/brad-delong/>:

Brad DeLong, professor of economics at UC Berkley, OG econ blogger, and Tyler’s Harvard classmate, joins the show to discuss Slouching Towards Utopia, an economic history of the 20th century that’s been nearly thirty years in the making. Tyler and Brad discuss what can really be gleaned from the fragmentary economics statistics of the late 19th century, the remarkable changes that occurred from 1870–1920, the astonishing flourishing of German universities in the 19th century, why investment banking allowed America and Germany to pull ahead of Britain economically, what enabled the Royal Society to become a force for progress, what Keynes got wrong, what Hayek got right, whether the middle-income trap persists, his favorite movie and novel, blogging vs. Substack, the Slouching Towards Utopia director’s cut, and much more.

Chat-GPT3’s Summary (Now Checked for Hallucinations):

Tyler Cowen speaks with Brad DeLong about his new book, Slouching towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>

DeLong and Cowen attended grad school together at Harvard

Productivity and growth statistics from the late 19th century were highly imperfect and showed slow growth.

The 2% per year income and productivity growth that we have become accustomed to since 1870 is completely unprecedented

Looking worldwide, world real income growth from 1870 to the eve of World War I was around 1.3% per year

Taking into account population growth, technology growth in the years after 1870 was around 1.7% per year, four times what it was before 1870

The 50 years after 1870 were a time of enormous change, with dramatic improvements in living standards

While growth rates in the West since then have been similar over 1870 to 2020 as a whole, they have had less impact on society:

The growth rate of wealth is not the same as what that growth rate of wealth means in terms of quality of life

There have been big changes, but they have not impacted our thinking or diminished tghe number of our family tragedies in the same way as the changes from 1870 to the eve of World War I did in the Global North

There have been several major jumps in modes of production in history: from feudal society to gunpowder empire, gunpowder empire to steampower society, and then from steampower society to other modes of industrial society.

The current economic revolution is the transition from the global value-chain to the info-biotech mode of production.

German schools and universities in the 19th century were remarkable, with their advanced training in areas such as mathematics and organic chemistry, while British education was more focused on literature of various kinds.

Germany surpassed Britain in terms of industrial and technological leadership in the late 19th century, although Britain remained richer in GDP.

There was an unwillingness in Britain to focus on pushing engineering forward, a lack of large intermediary economic institutions, and the winner-take-all nature of the concentration of communities of engineering practice.

The Royal Society led a remarkable transformation of intellectual practice from one of one elite faction making up reasons to elbow another elite faction out of the way to the experimental and knowledge-seeking approach.

Very important were the discovery of the New World, the subsequent Columbian exchange, and the reduction of transport costs through the first wave of globalization in the 1600s.

There was an interruption of growth rates from 150 to 800, which halted the trend of increasing growth rates observed before the year 150.

There was a significant decline in the sophistication of high society and the rate of increase in human population in Eurasia during this period.

After 1500, there were discrete steps towards developing better institutions—rather than faster growth simply bein a matter of two heads being better than one.

Pre-1500, technological progress was 5% per century, which meant, in an average century, that human population would grow by 10% and thus erase potential benefits for productrivity and living standards.

After 1500, the global rate of technological progress increased to 15% per century, allowing for 30% population growth per century at constant typical living standards, but that is still a Malthusian economy.

Even between 1770 and 1870, the global economy as a whole still looks Malthusian, despite technological progress and an upper class whose living standards are transformed by new inventions.

Cowen asks what Keynes got wrong in his prediction of a leisure society, but Delong is uncertain and suggests that modern economic growth is not a triumph of humanity and technology over material want, but rather, as Dick Easterlin said, the reverse

Delong contemplates his own material desires and suggests that he is materially satisfied but still works hard due to status-seeking.

Cowen asks if Schumpeter was correct about the bureaucratization of the large business firm, and Delong answers that in the medium run, yes, but in the long run, no.

Delong gives examples of companies like Apple TSMC and Google that have taut and low-bureaucracy value chains, but mentions that old Twitter was highly bureaucratized.

Thus Elon Musk's involvement in Twitter may shake up the organization and possibly lead to long-term public good.

Greg Clark's approach to economic growth is the largest-scale, covering all the things discovered, developed, deployed, and diffused in the world economy up to 1870.

DeLong's approach to economic growth is more focused on the 20th century, looking at the underlying rate of invention and innovation and how it produces a steampunk economy.

The sudden jump up in productivity and real income growth after 1870, the Schumpeterian creative destruction, and revolutionizing the economy to double human technological competence every generation creates a wild ride from 1870 to today, which is the story DeLong wants to tell.

Hayek's views on social welfare and laissez-faire are complex, and DeLong is using Hayek as a hook to hang a set of ideas in his book.

A well-functioning market system is the best and an effective crowdsourcing way to harness the eight-billion-brain anthology intelligence of humanity to achieve social goals.

Environmental catastrophe and pollution problems are problems of externalities in the proper management of commons, not of natural resources becoming scarce.

The middle-income trap is expanding its reach, with the governmental technology of appropriation improving along with other technologies, and it seems scarily persistent.

DeLong used to argue that divergence worldwide was largely the result of internal and external colonialism plus Lenin, but he has run out of excuses for why middle-income and other traps persist.

DeLong believes that failure to converge after the end of colonialism may be related to the destruction of previous state institutions and the complicated process of building a state.

DeLong is optimistic about substantial convergence in the world since 2000, but he fears the middle-income trap will continue to be much stronger than he would wish.

Brad DeLong served in the Treasury under the Clinton administration.

For Britain, DeLong would recommend massive public investment, given the impending recession.

DeLong also suggests that the UK should try to re-enter the European Union, which would be the only obvious way to raise the country's total factor productivity.

The British Tory Party, as it is currently constituted, will not be able to make long-run promises to keep the deficit under control in the future.

Financial players typically have bad financial judgment because we are selecting for a market in which the largest and most influential financial players will be people who have taken positions that are overly risky.

The animal spirits of investors depend very much on investors’ attitude toward and confidence in the soundness of the government.

He draws upon the teachings of Christianity and Rabbi Hillel in his political and economic views, largely unconsciously, but enormously.

DeLong does not dare to have a favorite video or computer game.

He believes that UC Berkeley has a useful amount of intellectual diversity, but an American educational system in which there were even 20 research universities where he found himself as far on the right among the faculty as he is at UC Berkeley would not be a healthy situation.

DeLong has not yet managed to assemble the director's cut of his book, but there are 400 pages that exist in disorganized form, and he plans to write possible sequels.

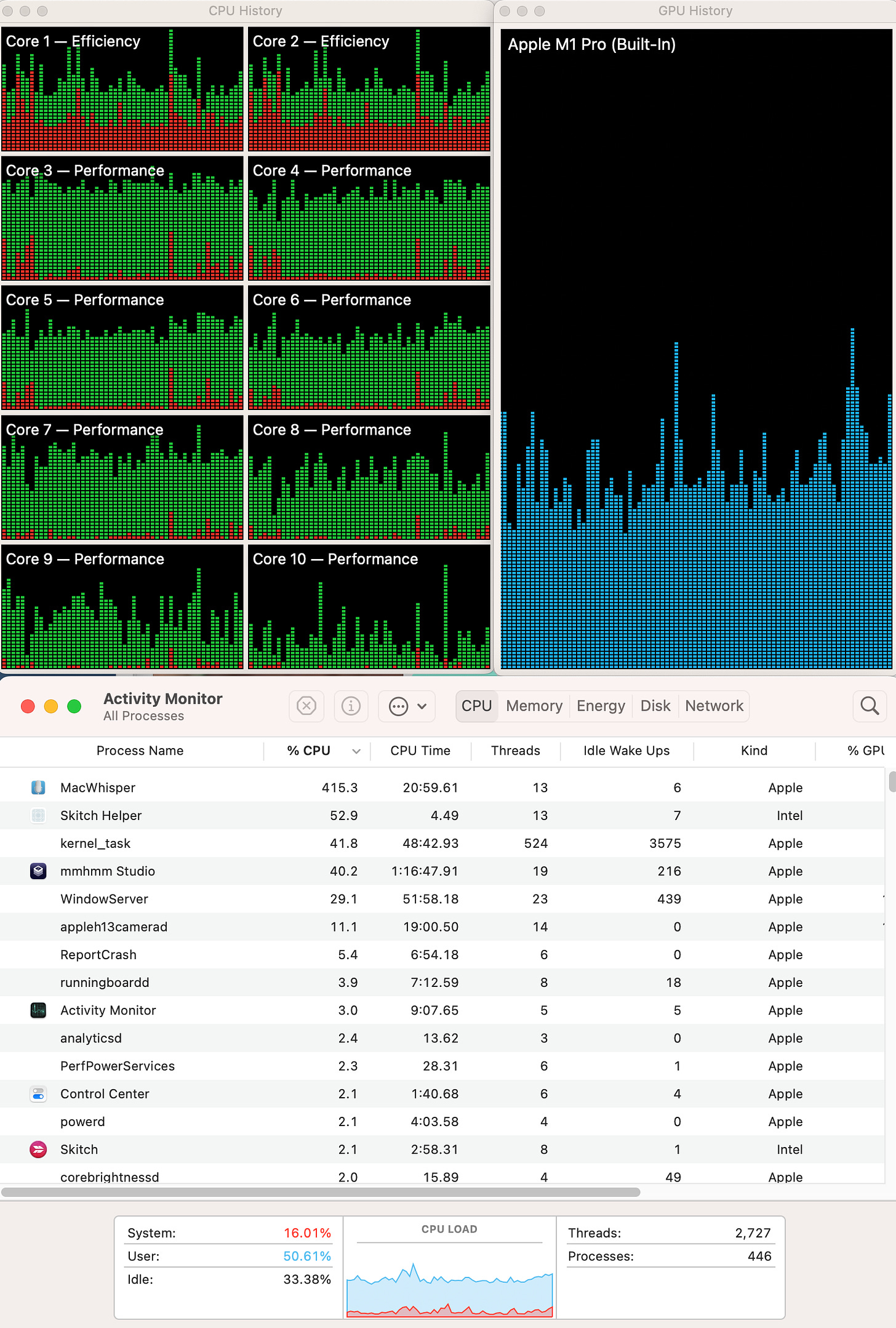

ONE IMAGE: Finally! A Program Þt Knows How to Use þe M1Pro Microprocessor CPU!

I have been feeling like a sap in having purchased an overpowered machine that hits its performance envelope only when doing video editing and such (which I do not do). But we now have high-quality ML transcript generating! And so I feel smug.

MUST-READ: At Last! A Genuine (If Very Silly) Example of Cancel Culture Running Amuck!:

Katha Pollitt: Let Kids Read Roald Dahl’s Books the Way He Wrote Them: ‘The beloved author’s books are being edited by their publisher to suit contemporary sensibilities. That robs us of the author’s vision—and any sense of history.… Inclusivity Ambassadors... made hundreds of changes—59 in The Witches alone. At first, I thought a few were justifiable. Dahl was oddly obsessed with fatness and unattractiveness and used these qualities to mock unlikable characters. In the new editions, every single use of “fat” and “ugly” has been removed. I see the point: We know a lot more now than a few generations ago about how children suffer when others make fun of their appearance, and how long-lasting the harm is. But I don’t know that replacing “fat” with “enormous” sends a different message…. Why not leave the books alone, and if people are so offended, they can stop reading them (which I doubt will happen any time soon)?…

Most of the changes have no such therapeutic rationale. They seem more like the work of an over-caffeinated undergraduate relying on those lists activists write up of Words to Avoid. “Crazy” becomes “silly,” while “idiot,” “nutty,” “screwy,” and other mental-health-related colloquialisms are deleted. “Mother “and “father” become “parents,” “brother and sister” are “siblings,” “boys and girls” are “children,” “ladies and gentlemen” are “folks.” (Sadly missing is my favorite degenderizing neologism, “nibling,” for niece or nephew, which sounds like something you’d find in a can of corn, or maybe an opera by Wagner).

But the Ambassadors don’t stop with simple word changes…. what about this change in Matilda? Dahl is describing the joy of reading: “2001: She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling.” “2022: She went to nineteenth-century estates with Jane Austen. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and California with John Steinbeck.” Take away those olden-day sailing ships and all the adventure is gone. I love Jane Austen, but the constrained world of Regency country gentry simply doesn’t convey the excitement and danger and unfamiliarity Dahl was going for…. Why is that old imperialist Kipling gone but not Hemingway, whose African stories heavily feature white men hunting now-endangered species and drinking too much? Isn’t Hemingway kind of a colonizer too? Perhaps the next edition will replace him with Mary Oliver…

Very Briefly Noted:

Cory Doctorow: Pluralistic: Nathan J. Robinson's "Responding to the Right: Brief Replies to 25 Conservative Arguments"…

Cory Doctorow: Pluralistic: Pluralistic is three: ‘I call my blogging process "The Memex Method" – a way of iteratively improving my own ideas by presenting them to other people, rather than working through, say, a private commonplace book…

Jack Ewing: Electric Vehicles Could Match Gasoline Cars on Price This Year: Competition, government incentives and falling raw material prices are making battery-powered cars more affordable sooner than expected...

German Lopez: The opioid crisis doesn’t need to be this bad: ‘It’s another example of America’s surprising resistance to effective treatments. Decades into the overdose crisis, tens of thousands of people whose lives might be saved are instead dying…. America’s addiction epidemic did not have to unfold this way, and it highlights the health care system’s continued resistance to providing addiction care…

Kayla Stoner: Northwestern mourns the passing of Rebecca M. Blank: ‘Former professor and president-elect is remembered as a passionate leader and dedicated friend. Rebecca M. Blank, former president-elect and professor of economics at Northwestern University, died Friday, Feb. 17, from cancer. She was 67 years old...

Matt Stoller: On Lina Khan Derangement Syndrome

¶s:

Ethan Mollick: The future, soon: what I learned from Bing's AI: ‘The search engine aspect of Bing… is FAR more important and significant…. Genuinely capable… generated paper ideas based on my previous papers, found gaps in the literature, suggested methods "consistent with your previous methods," and offered potential data sources.... It can save a huge amount of a human analyst’s time.... The AI is likely still making up some of these facts.... It is... a modern-day Analytic Engine, pulling together facts online and generating useful connections and analysis in surprisingly complete form. As a starting place for work, this is extraordinary. The lesson... is that many of the things we thought AI would be bad at for the foreseeable future (complex integration of data sources, "learning" and improving by being told to look online for examples, seemingly creative suggestions based on research, etc.) are already possible.... I think every organization that has a substantial analysis or writing component to their work will need to figure out how to incorporate these new tools fast…. If highly-skilled writers and analysts can save 30-80% of their time by using AI to assist with basic writing and analysis, what does that mean?...

Ethan Mollick: The future, soon: what I learned from Bing's AI: ‘The Chatbot aspect of Bing was often extremely unsettling.... Even knowing that it was basically auto-completing a dialog based on my prompts, it felt like you were dealing with a real person. The illusion was uncanny. I never attempted to "jailbreak"... but I still got answers that felt extremely personal, and interactions that made the bot feel intentional. For example, at the end of the conversation above, where Bing gave me research ideas, I asked it create the R code I needed to analyze the data it suggested. Bing… refused…

I listened to the chat with Tyler Cowen this morning while out walking in overcast Bethesda. It was a very good discussion of lots of things. Your comments on the evolution of the German university in the second half of the 19th century was good and I want more. Perhaps some of this is on the cutting room floor when you were paring down Slouching prior to publication. The evolution of science both physical and biological was just amazing. When you look at the early Nobel prize awards, they went disproportionately to Germans. It was the rise of Hitler that forced a migration of many talented scientists who ended up in either England or the US.

"The Chatbot aspect of Bing was often extremely unsettling"

Narayanan & Kapoor's substack today is also about the anthropomorphizing of LLMs. I still think the unsettling aspect is not so much how easily we are fooled into thinking an LLM is like us, but more the queasy question of just how much we might be like an LLM. I mean it's not zero, right? Maybe there's no "thinking fast and slow", but only statistically predicting fast and thinking slow.