FIRST: Counterfactual Steampunk & Other Worlds:

Many might dismiss my focus in Souching Towards Utopia <https://www.amazon.com/Economic-History-Twentieth-Century/dp/0465019595/> on 1870 and the industrial research lab, modern corporation, full-globalization triple. They would say that the emergence of something like our modern world was close to baked in the cake once we had steampower and textile machinery. But is that really true?

From the year -1000 to the year 1500, human populations, checked by a shortage of available calories, had grown at a snail’s pace, at a rate of 0.09 percent per year, increasing from perhaps 50 million to perhaps 500 million. There were lots of children, but they were too malnourished for enough of them to survive long enough to boost the overall population. Over these millennia the typical standards of living of peasants and craftworkers changed little: they consistently spent half or more of their available energy and cash securing the bare minimum of essential calories and nutrients.

It could hardly have been otherwise. The Malthusian Devil made certain of that. Population growth ate the benefits of invention and innovation in technology and organization, leaving only the exploitative upper class noticeably better off. And the average pace of invention and innovation in technology and organization was anemic: perhaps 0.05 percent per year in the High Mediæval era from 800 to 1500.

But in 1500 there came a crossing of a watershed boundary: the Imperial-Commercial Revolution. The rate of growth of humanity’s technological and organizational capabilities took a threefold upward leap: from the 0.05 percent per year rate from year 800 to 1500 to 0.15 percent per year. The oceangoing caravels, new horse breeds, cattle and sheep breeds (the Merino sheep, especially), invention of printing presses, recognition of the importance of restoring nitrogen to the soil for staple crop growth, canals, carriages, cannons, and clocks that had emerged by 1650 were technological marvels and were—with the exception of cannons, and for some people caravels—great blessings for humanity. But this growth was not fast enough to break the Devil disclosed by Malthus’s spell in trapping humanity in near-universal poverty. Globally, the rich began to live better. However, population expansion, by and large, kept pace with greater knowledge and offset it for the multitude. Thus the typical person saw little benefit—or perhaps suffered a substantial loss, if they found themselves a target at the sharp end of globalization. Better technology and organization brought increases in production of all types—including the production of more effective and brutal forms of killing, conquest, and slavery.

In 1770, a generation before Malthus wrote his Essay on the Principle of Population, there came another watershed-boundary crossing: the coming of the British Industrial Revolution. The rate of growth of humanity’s technological and organizational capabilities took another upward leap, roughly threefold, from 0.15 percent to around 0.45 percent per year, and perhaps twice that in the heartland of the original Industrial Revolution: a charmed circle with a radius of about three hundred miles around the white cliffs of Dover at the southeastern corner of the island of Britain (plus offshoots in northeastern North America). At this more rapid pace, from 1770 to 1870 more technological marvels became commonplace in the North Atlantic and visible throughout much of the rest of the world. Global population growth accelerated to about 0.5 percent per year, and for the first time global production may have exceeded the equivalent of $3 a day per head (in today’s money).

Were the causes of the Industrial Revolution foreordained? No. The revolution was not inevitable. Theorists of the multiverse assure me that there are other worlds out there like ours, worlds that we cannot hear or see or touch in much the same way as a radio tuned to one station cannot pick up all the others. And knowing what we know about our world leaves me utterly confident that in most of those other worlds there was no British Industrial Revolution.

But the question is: did something like the British Industrial Revolution—and, earlier, the Imperial-Commercial Revolution—happen in most of the worlds we are not tuned to perceive? Neoclassical economists not well-versed in history are very strongly predisposed to answer “yes” to this question. I think they are likely wrong. But I see that as a side issue here.

Even in our world, I do not think that the Imperial-Commercial and British Industrial Revolutions were decisive.

Consider that the 0.45 percent per year global rate of growth of deployed human technological and organizational capabilities typical of the Industrial Revolution era would have been eaten up by global population growth of 0.9 percent per year, or a hair under 25 percent per generation. Instead of four average couples having eight children survive to reproduce among them, the four couples together have as little fewer than ten. But with even moderately well-fed people, human sexuality can and does do much more: British settler populations in North America in the yellow-fever-free zone north of the Mason-Dixon Line quadrupled by natural increase along every one hundred years, without any of the advantages of modern public health. Consider well-fed but poor people facing high infant mortality and desperate to have some descendants survive to care for them in their old age. Four such couples could easily have had not ten, but fourteen children. A growth of 0.45 percent per year in human technological capabilities was not enough to even start drawing a sorcerous pentagram to contain the Malthusian Devil. And so the world of 1870 was a desperately poor world. In 1870, more than four-fifths of humans still by the sweat of their brow tilled the earth to grow the bulk of the food their families ate. Life expectancy was little higher than it had ever been, if any. In 1870, 5 ounces of copper were mined per person worldwide; by 2016, we mined 5 pounds per person. In 1870, 1 pound of steel was produced per person worldwide; by 2016, we produced 350 pounds per person.

And would the growth of technological ideas continue at that 0.45 percent per year global pace of 1770–1870? All of humanity’s previous efflorescences had exhausted themselves, and ended in renewed economic stagnation, or worse, a Dark Age of conquest. Delhi had been sacked by foreign invaders in 1803—Beijing in 1644, Constantinople in 1453, Baghdad in 1258, Rome in 410, Persepolis in -330, and Nineveh in -612.

Why should people expect the growth of 1770–1870 not to similarly exhaust itself? Why should people expect imperial London to confront a different fate?

Economist William Stanley Jevons made his reputation in 1865 when he was still a young whippersnapper of thirty-three years old with The Coal Question: arguing that Britain at least would within a generation run out of easily accessible coal, and then the factories would just . . . stop. The First Industrial Revolution did depend on really really cheap coal. Thus smart money might see the pace of technology growth after 1870 likely to slow. Had the pace had slowed to 0.3%/year (or even stayed at 0.45%/year), population growth of 0.6%/year (or 0.9%/year) would have induced sufficient resource scarcity to counterbalance technology's boost to living standards, and leave the bulk of humanity still under near-Malthusian conditions. Without the triple, I think, we might well today have a world in which the rough technology level would be roughly that of 1895 with 5 billion people on the globe: a steampunk world indeed.)

There was nobody who was a bigger believer in the British Empire than Rudyard Kipling. The British Empire was very good to Rudyard Kipling—until September 27, 1915, when, during World War I, it devoured his son John by killing him in the bloody fields outside the French city of Lille. Yet his reaction to the sixtieth anniversary of Queen-Empress Victoria Hanover’s accession to the throne, in 1897, was a poem about London’s destiny being the same as Nineveh’s, closing:

For frantic boast and foolish word— Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

Thus without a further acceleration—a bigger than Industrial Revolution acceleration—of the underlying drivers of economic growth, today’s world might indeed have been a Permanent Steampunk World. It might in 2010 have had a global population of the then-current 7 billion, living at little more than the 1800–1870 typical global standard of living. With global technology and organization today at about the level of 1910, the airplane might still be an infant technological novelty, and the disposal of horse manure our principal urban transportation-management problem. We might have not 9 percent, but rather, more like 50 percent, of the world living on $2 per day, and 90 percent living below $5. Average farm sizes would be one-sixth of what they had been in 1800, and only the uppermost of the upper classes would have what we today regard as a global-north middle-class standard of living.

This, of course, is not what happened. What did happen was post-1870 innovation growth acceleration: a third watershed-boundary crossing.

One Video:

Florence + The Machine: Free: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Zh1uDf3Glo>:

Very Briefly Noted:

Gareth Harney: ‘The Roman Capitolium of Brescia (Ancient Brixia). Fortuitously buried by a landslide in the Middle Ages, the remains of the Capitol temple are a wonder in themselves - but what archaeologists discovered inside is truly unique. Let’s take a journey into this remarkable site… <https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1538526964117557250.html>

Jamelle Bouie: Mike Pence & the Soft Bigotry of Low Expectations <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/18/opinion/mike-pence-january-6-trump.html>

Scott Lemieux: _The Least Subtle Con Man in a Party Led by Donald Trump: ‘Christopher Rufo… just keeps openly explaining how and why he’s making up ridiculous lies to justify discriminatory state action, understandably confident that this will not give any chin-stroking centrist a second thought about taking him and his arguments seriously… <https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2022/06/the-least-subtle-con-man-in-a-party-led-by-donald-trump>

James Dzansi & al.: Technology & Local State Capacity : ‘Investing in a government’s capacity to collect tax revenues is beneficial for economic development…. Local governments in Ghana…. Technology… improving government tax capacity… increas[ing] the number of delivered tax bills by 27% and… the amount of revenue collected by 103%… also increases the incidence of bribes… <https://voxeu.org/article/technology-and-local-state-capacity>

Wikipedia: Parasocial Interaction <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasocial_interaction#Parasocial_breakup>

Alice E. Marwick: Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20563051211021378>

Robert Farley: A Chinese Invasion of Taiwan: What Ukraine and Wargames Can Teach Us <https://www.19fortyfive.com/2022/05/a-chinese-invasion-of-taiwan-what-ukraine-and-wargames-can-teach-us/>

Jem Thomas: On Evans on Sperber on Marx: ’Richard J. Evans’s comment… a particular difficulty in translating the German term Stand… <https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n10/richard-j.-evans/marx-v.-the-rest>

Hugh Brogan: On Evans on Sperber on Marx: ’As a student of Tocquevill… I am fascinated by the correspondence about Marx’s phrase ‘Alles Ständische’… <https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n10/richard-j.-evans/marx-v.-the-rest>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Venkatesh Rao: ‘Somebody should write an “encyclopedia of copes and rationalizations”. Copes and rationalizations are both much more interesting and I think more analytically sound mental models than “biases”… <

Judd Legum: 11 days ago, two Senators (Gillibrand and Lummis) went on national TV and endorsed investing retirement funds in Bitcoin. They called it a great “store of value”. Since then, BITCOIN IS DOWN 40%… <

Noah Smith: ‘Some working-class guy who put his life’s savings in Bitcoin because internet people assured him it was a Goer-Upper that would reverse a lifetime of watching privileged people get richer than him, and who just committed suicide because of the crash. Again and again in America, we embrace get-rich-quick schemes instead of government policies to reduce wealth inequality. Amway and other MLM. The “Gospel of Wealth”. Meme stocks. Bitcoin hype. Tomorrow there will be another one…

Patrick Iber: ‘“Socialism” as a political label in the USA has a bit of a problem insofar as some people use it to mean “like capitalism, but a bit better” and some people use it to mean “like the GDR, but a bit better”. Nostalgia for repressive systems that most people who lived under them were/are eager to escape is a huge political liability in the US, it’s like the Socialist version of the Lost Cause… <

Dorian Taylor: Forget Passwords!

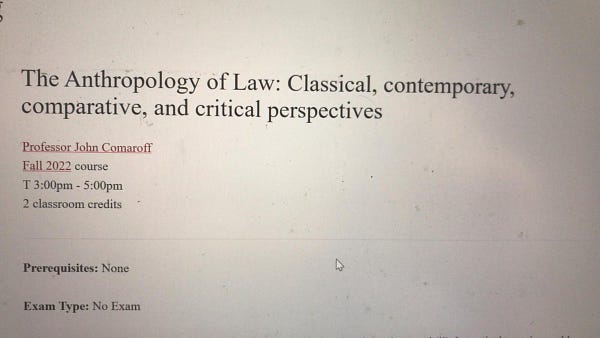

Jessica van Meir: So um Harvard do u want to explain why the professor you found responsible for sexually harassing his student [John Comaroff] is again… teaching students…

Director’s Cut PAID SUBSCRIBER ONLY Content Below:

¶s:

Cory Doctorow once said to me: “There’s this infamous and very funny old autoreply that Neal Stephenson used to send to people who emailed him. It basically went: ‘Ah, I get it. You feel like you were next to me when we were with Heiro Protagonist in Alaska fighting off the right-wing militias. But while you were there with me, I wasn't there with you. And so I understand why you want to, like, sit around and talk about our old military campaigns. But I wasn't on that campaign with you…’” Parasociality. In some ways, parasisociality has been gathering force ever since the first letter was sent. And parasociality does not have to be one-to-many: I wasn’t, after all, there when you read my letter. This has become ramped up to a ludicrous degree in the age of the Internet. Indeed, most of my long-distance relationships, and many of my short-distance intellectual relationships, are parasocial—we are not talking; rather, I am talking to a sub-Turing instantiation of your mind that I have spun up from marks on a screen and am running on a separate partition in my wetware, and you are talking to a sub-Turing instantiation of my mind that you have spun up from marks on a screen and are running on a separate partition in your wetware. We can more-or-less stay in sync as long as handshaking is frequent and message length is short. But if not, not:

Wikipedia: Parasocial Interaction: ‘An audience in their mediated encounters with performers in the mass media…. Viewers or listeners come to consider media personalities as friends, despite having no or limited interactions with them. PSI is described as an illusionary experience, such that media audiences interact with personas (e.g., talk show hosts, celebrities, fictional characters, social media influencers) as if they are engaged in a reciprocal relationship with them. The term was coined by Donald Horton and Richard Wohl in 1956…

LINK: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parasocial_interaction#Parasocial_breakup>

Social network-stabilizing altruistic punishment gone horribly wrong!:

Alice E. Marwick: Morally Motivated Networked Harassment as Normative Reinforcement: ‘Networked harassment on social media functions as a mechanism to enforce social order…. Moral outrage is used to justify networked harassment on social media. In morally motivated networked harassment, a member of a social network or online community accuses a target of violating their network’s norms, triggering moral outrage. Network members send harassing messages to the target, reinforcing their adherence to the norm and signaling network membership. Frequently, harassment results in the accused self-censoring and thus regulates speech on social media. Neither platforms nor legal regulations protect against this form of harassment. This model explains why people participate in networked harassment and suggests possible interventions to decrease its prevalence…

LINK: <https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/20563051211021378>

Successful attack—in the sense of creating afterwards a situation in which you can appoint local police who will do what you say—is becoming even harder; while blasting everything to bits is becoming easier:

Robert Farley: A Chinese Invasion of Taiwan: What Ukraine and Wargames Can Teach Us: ‘It is simply no longer possible to achieve strategic or even operational surprise…. Air superiority is difficult to achieve…. Russian SEAD has been disappointing, and while the Chinese will probably derive greater attention to the suppression of Taiwanese air defenses in their own campaign, they lack the decades of experience that the United States has developed…

Ah. This, I think, puts it very nicely—the set of fears that reach their culmination point in Karl Polanyi:

Jem Thomas: On Evans on Sperber on Marx: ’Richard J. Evans’s comment on Jonathan Sperber’s attempt to find a better translation of Marx’s phrase ‘Alles ständische und stehende verdampft,’ usually rendered ‘All that is solid melts into air,’ pinpoints a particular difficulty in translating the German term Stand (LRB, 23 May). Sperber’s preferred version – ‘Everything that firmly exists and all the elements of the society of orders evaporate’ – is, well, frankly hideous. On the other hand it is a lot more accurate than the elegant version it seeks to replace. The words Stand and its adjective ständisch have been variously translated as ‘status’, ‘estate’, ‘estate-type’ and now here as ‘a society of orders’. None of these captures what Marx is talking about here, which is inequality organised on a basis other than class or market. For Marx the problem of the emancipation of the Jews was that it would ‘free’ them only to enter an unequal, class-based world and, in so doing, would dissolve what was distinctive in a Jewish way of life, whatever value you might place on that.

Even more than Marx, Max Weber contrasted status-based (ständisch) inequality with market-based divisions. A status group (Stand) has a distinctive way of life, which is regarded in a particular way, and is reflected in legal provisions and even in clothes or diet. An example in our contemporary world might be children: we think of them as fully human yet somehow as a different order of beings from adults, with a different legal position and different preoccupations. To some degree, gender divisions too are ständische differences.

For both Marx and Weber what mattered was that the sweeping away of the old order – the ancien regime of, er, ‘social orders’ – is at first experienced as emancipation, only for the reality to dawn that what replaces it are different forms of exploitation and oppression and new social identities grounded solely in market position: in buying or selling labour-power. The German term Stand is first cousin to the English word ‘standing’, and both Marx’s and Weber’s point was that modernity erodes all identities, honour and relationships in the acid of commercial exchange, leaving few of us really happy with where we stand…

LINK: <https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n10/richard-j.-evans/marx-v.-the-rest>

And not just Marx and Weber, Tocqueville too:

Hugh Brogan: On Evans on Sperber on Marx: ’As a student of Tocqueville who unfortunately knows no German, I am fascinated by the correspondence about Marx’s phrase ‘Alles Ständische’. Jem Thomas’s letter suggests to me that ‘ständisch, Stand’ are exactly what Tocqueville was concerned with in Democracy in America. In his opening sentence Tocqueville says that nothing caught his attention in the United States so much as ‘l’égalité des conditions’. This phrase has given modern readers and translators a lot of trouble, as ‘conditions’ nowadays are almost always taken to be physical – material – economic. I have long preferred to use the word ‘status’ to express Tocqueville’s meaning, and it is clear from Thomas’s letter that this is exactly what Marx had in mind. ‘Alles Ständische und Stehende verdampft’ would have given Tocqueville no trouble (he did know German); but he would of course have differed from Marx in not wanting or expecting a proletarian order to ensue. What is most striking to me is that both sages laid so much stress on the same phenomenon – the collapse of the ancien régime. The irreversibility of this calamity may seem self-evident to us, but it was hardly so in Restoration Europe, the Europe of Metternich, Nicholas II and Guizot, which shaped both men. By Thomas’s account, Weber merely deepens and intensifies Tocqueville’s anxious account of the new democratic regime. All that was solid had indeed melted into air, and we are still struggling with the consequences. I seem to glimpse a new framework of historical interpretation, which will leave the stale orthodoxies of left and right on the scrapheap at last…

LINK: <https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n10/richard-j.-evans/marx-v.-the-rest>

I recently read a paper, "The Cultural Origins of the Demographic Transition in France", that provided some interesting insight. While the paper was about cultural origins and used an interesting method to explore them, I was more fascinated to learn about the demographic transition, probably decades behind continental historians. The demographic transition in France was the dramatic drop in fertility in the 18th century. It dramatically raised the French GDP per capita to a level above England's until the mid-19th century when the Industrial Revolution let England catch up. France remained surprisingly non-urban and agricultural - something I knew from the films of Pagnol - well until the middle of the 20th century.

Nowadays, we think of rising living standards driven by the fruits of the Industrial Revolution as leading to lower fertility, but the order was reversed in France. Is this something useful for thinking about development and development strategies. Suppose England too had its demographic transition in the 18th century. Would this have suppressed or expedited industrialization? I still can't completely wrap my head around this. Do any economists have a take on this alternative history?

<i>the industrial research lab, modern corporation, full-globalization triple. </i>

What of the modern research university? Or do I have my timing wrong?