DAY 3: LECTURE NOTES: 2. Ensorcelled by þe Devil of Malthus: 2.1. Þe Logic of þe Malthusian Economy

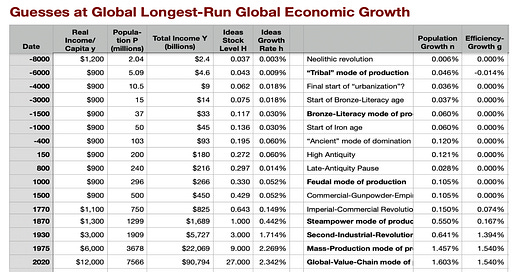

DRAFT lecture notes for the spring 2023 instantiation of UC Berkeley Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth: Population is an increasing function of income; income is an increasing function of re...

From 70,000 to 10,000 Years Ago

70,000 years ago, back in the Early Paleolithic Age, there were perhaps 100,000 of us—100,000 East African plains apes who looked like us, moved like us, acted like us, talked like us, and from whom the overwhelming proportion of all of our heredity is derived. Yes, we have small admixtures (5%?) from other groups and subspecies and maybe even species, but overwhelmingly we are those proto-hundred-thousand's children. Each of them who has living descendants today has a place—has an astronomical number of places—on each of our family trees. (No, I do not believe that the Khoisan are in any sense “a separate creation”, diverging from those who became the rest of us 200,000 years ago—lots of back-and-forth gene flow over those 200,000 years.)

Back then we were very, very smart herd animals. We gathered, we hunted (some), we protected ourselves, we made stone and wood tools, we understood our environment, we manipulated our environment, we communicated with each other, we cooperated and we fought, we talked, and we did the things that humans.

Flash-forward 20,000 years to 50,000 years ago, on what we think was the eve or possibly in the middle of the overwhelming majority of our then-ancestors’ final major radiation-migration out of the Horn of Africa, to the rest of Africa, and across the Red Sea to the wider world. There were then, perhaps, one million of us. We had been very successful in amplifying our numbers, almost surely by crowding our near-cousins out of our common ecological niche in the Horn of Africa. We surely had some evolutionary edge relative to them, but what? Fully-developed language?

Our standard of living back then? If we had to slot it into emerging-markets standards of living in the world today, we might call it 3.50 dollars a day. Poverty, but not quite what the United Nations calls extreme poverty: natural resources were not scarce, our knowledge of our east African environment was profound, and we probably had to spend a little more than one-third of our waking hours collecting 2000 calories plus essential nutrients each day, plus enough shelter and fire and clothing that we were not unduly wet or cold. We were buff: life was strenuous. But we were short-lived: a life expectancy at birth of perhaps 25-30, for hauling around a family in our then-semi-nomadic lifestyle was dangerous: life was strenuous. And we were in rough ecological balance. The level of our technology? Normalized to our benchmark H 1870 = 1.0, that guessed standard of living and that guess at our then-numbers computes a level H-48000 = 0.0256 back 50,000 years ago,

Flash-forward another 40,000 years, to 10,000 years ago, on the very eve of the invention/discovery of agriculture and of animal domestication. Things were much the same, save that there were then not one million of us in East Africa but rather perhaps two-and-a-half million of us, well, pretty much everywhere. Our living standards were much the same as they had been. We had better tools, but they were of stone and wood, plus fur and fiber, and not yet metal: it was still the Mesolithic Age. Our knowledge of our environment—or rather environments—was more profound, and so was our power to manipulate them. But in each environment we lived in we found ourselves in rough ecological balance. As of -8000 the index H of human technological capabilities stands at 𝐻-8000 = 0.04.

Over the Paleolithic Era of stone and the Mesolithic Era of stone plus some pottery and textiles from 70 to 10 thousand years ago, the rate at which the stock of useful ideas about technology and organization was growing was 0.001% per year—and, with standards of living stagnant at an average of $3.5 dollars a day or so, the rate of growth of human populations was twice that: 0.002% per year, or 0.05% per generation: a typical generation would see, an average, 2000 people turn into 2001. What if growth over the generations had been much faster? Then, given the—very slow, 0.001% per year—rate of growth in useful ideas H, the population finds itself without sufficient resources to sustain itself and drops. What if growth over the generations had been much slower? The population would find itself better-nourished, with children's immune systems less compromised and women ovulating more regularly, and population growth would have accelerated. Malthusian equilibrium thus kept population growing along with useful ideas, and the rate of growth of useful ideas was very slow.

The Neolithic Revolution and the Agrarian Age to 1500, and Even After

Then, at the end of the gatherer-hunter age, comes the upward leap (or was it an upward leap) of the Neolithic—“New Stone”—revolution. The proportional rate of growth of ideas jumped up, massively, eleven-fold to 0.011% per year, during the -8000 to -6000 Neolithic Revolution: herding and agriculture were really good ideas. 2000 years after -8000 we are (poor) agriculturalists and (unsophisticated) herders of barely domesticated animals, with a human population of perhaps 7 million, but a lower living standard of perhaps 2.50 dollars a day, with an index 𝐻-6000 = 0.051.

Why a 2,5-fold multiplication of population in 2000 years or so? Because living was easier when you were sedentary or semi-sedentary: you no longer had to carry babies substantial distances, and you could accumulate more useful stuff than you could personally carry. Plus even early agriculture and herding were very productive relative to what had come before. Since life was easier, more babies survived to grow up and themselves reproduce.

Why a fall in the standard of living? Because population grew until humanity was once again in ecological balance, with population expanded to the environment's carrying capacity given technology and organization. But what keeps population from growing further? The fact that life has become harder again. But it became harder in a different way: agriculturalists are shorter—figure about three inches, 7.5 centimeters—malnourished, prone to endemic diseases, and vulnerable to plagues relative to gatherer-hunters. Biologically, it would seem much better to be a typical person in the gatherer-hunter than in the post-Neolithic Revolution agrarian age: your life expectancy is no less, your daily life presents you with more interesting and less boring cognitive problems, and you are much more buff and swole.

Jared Diamond believes—or at least whoever wrote the title of his article believes—that the invention of agriculture was, as the title says, a bad mistaker: humans would be better-off had we remained gatherer-hunters.

Technological progress—the discovery, invention, development, deployment, and diffusion of useful and valuable ideas about how to manipulate nature and organize humans—continued at 0.018% per year from -6000 to -3000, the end of the Stone and the start of the Literacy and Bronze Age. In the Bronze and then the Iron Age agriculture, craftwork, organization, literacy, and more advance civilization: from -3000 to -1000, and then from -1000 BC to the year 1, we see H rise at first 0.03% per year, and then 0.06% per year, with a year-150 human population of 200 million. St least half of that year-150 population was collected in three great empires—Roman, Parthian, and Han—enforcing imperial peace, and together spanning Eurasia from what is now Vladivostok to Cadiz and from Hainan to Scotland.

With all that comes further development of agriculture, craftwork, organization, literacy, civilization: by year 150 the index 𝐻 = 0.27, but our standard of living is not significantly higher for there are now 200 million of us on the globe.

Malthusian Equilibrium

This is a Malthusian Equilibrium: a vast tenfold improvements in technological and organizational capabilities from -6000 to 1500, from 0.43 to 0.43; but virtually all of that improvement going to support a 70-fold increase in human population; and with only 1/100 the potential natural resources at their disposal, the typical peasant or craftsman in 1500 was able to use that technology to eek out roughly the same standard of living as their predecessors 7.5 millennia before.

There is definitely a spurious precision here.

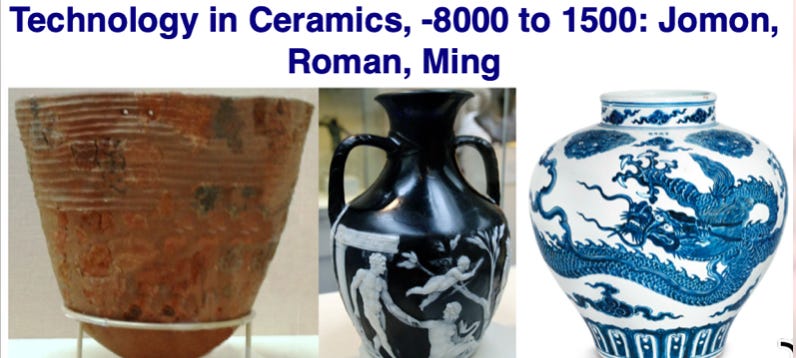

Even if we could gain universal assent as to technological capability in, say, ceramics and each of the other aspects of human productivity and creativity, squashing multi-dimensional objects down into a single one-dimensional index simply cannot be done. All we can say is that if there were an economy simple enough for such an index to be accurate, and if its levels of productivity corresponded to those we assign to the real history, then its index of human technological and organizational capabilities would be our H.

Nevertheless, I find such a framework very useful as a metaphor in organizing my thoughts. The numbers assigned to H do carry meaning. Look at pottery in -8000, in year 150, and in 1500:

Queen Victoria does not appear to have been a much better queen than Queen Elizabeth. But, from all historical accounts, Gloriana appears to have been perhaps four times as happy as happy a woman as the Widow of Windsor.

In this long Agrarian Age of Malthusian equilibrium from -6000 to sometime between 1500 and 1930, depending where you lived, humanity (except for a relatively narrow slice of aristocrats at the top of the social hierarchy, and those lucky enough to be able to lick up the crumbs that fell from the aristocrats’ tables) lived in what we would regard as dire poverty. They were close to the edge of subsistence, in the sense that had the population been even moderately poorer, the population would not have managed to reproduce itself in the next generation: too many women would have missed ovulation from malnutrition, too many malnourished children with compromised immune systems would have been taken out by the common cold, and too little sanitation made it a truly golden age for plague and dysentery.

Consider: a preindustrial pre-artificial birth-control population that is nutritionally unstressed will triple in numbers every 50 years or so. That was the experience of the conquistadores and their descendants in Latin America. That was the experience of the English and French settlers coming in behind the waves of plague and genocide that had decimated the indigenous Amerindian population in North America. That was the experience of the Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian settlers on the Pontic-Caspian steppe, after the armies of the gunpowder empires, most notably of Yekaterina II Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov (neé Sophie),Tsarina of All the Russias, drove out the horse nomads and opened the black-earth regions to the plow.

But back in the Agrarian Age it took the human population not 50 but 1500 years to triple. The population in the year 1500 of 500 million was only three times what it had been in the year one. And yet is there anything that parents would work harder for and spend more effort on than trying to ensure that their children would survive to reproduce? Yet they could not do so, at least not to any extent to make the rate of population growth more than glacial. And note that this was not because of a shortage of births: 8 pregnancies is typical for an Agrarian Age woman. Queen Anne Stuart had 17.

The fact that, in the Agrarian Age, human populations took not 50 but 1500 years to triple a measure of how poor, in the sense of being extraordinarily close to a biological population-sustaining limit humanity was back then.

Agrarian-Age historical patterns do appear to fit the Malthusian model. Under conditions of great nutritional stress, no artificial birth control and high infant mortality, families are desperate to have as many children as sociologically possible. They need to increase the chances that at least one child will survive to to care for them in their old age, should they attain one, and to carry on their memory. Thus a richer economy sees a higher rate of population growth. Given the absolutely glacial rate of technological progress and the discovery and deployment of ideas—maybe a 5% increase in the value of ideas over a century—the resulting increase in population causes resource scarcity: smaller farm sizes. That pushes the standard of living down, until women stop ovulating regularly and children's immune systems are so compromised that they are carried off by the common cold.

What if something happens to disturb the system either to increase or decrease the population by a lot or to jump up or down the level of the ideas stock or of resources? Then either a richer or poorer society will lead population growth to either accelerate or population to fall, until we are once again back at Malthusian stagnation.

Simulating a Malthusian Economy

Does this belong in the lecture? I think: yes. Here:

Inequality and Exploitation

Would it have been better to have been a working-class Briton around 1800 or a gatherer-hunter before -8000? Probably a gatherer-hunter.

On the one hand, if you are a gatherer-hunter you are buff! But there is lots of within-humanity violence: you run a substantial risk of being stabbed to death and having to watch your babies' brains bashed out against rocks. On the other hand, if you are an agriculturalist, you, have a chance of a long slow death from starvation and malnutrition. You are stunted, weak, with very bad teeth, and probably stupid from protein deprivation in utero. I don't think we really know what typical agrarian age diets did to brain function. We do know that they, that agrarian age mother's found themselves significantly compromised health-wise as the infant to be leeches calcium out of the mother's bones and teeth to build itself.

There is little to choose with respect to life expectancy. Infant mortality appears to be the same.

Oh: and gatherer-hunters face interesting lives in which they constantly solve environmental and social puzzles, sort of a la a slow-motion version of Super Mario. By contrast, the agrarian age sees you doing the same damn thing day after day after day. Plus the Agrarian Age brings patriarchy, and much more wealth and status inequality. This is so unless you are lucky enough to be one of the lords and masters. But if you are not, you run the risk that the lords and masters will find a way to torment you impressively to reinforce the principle that people should pay their rent and their taxes on time and in full. This is almost surely a big negative sum in the Agrarian Age: There are always many more to be dominated than there are to feel good about themselves because they dominate.

In this Agrarian-Age, from the discovery of agriculture on up to and beyond 1500, civilization–if you want to call it that—depended almost entirely on exploitation. It needed an upper class that took from the peasants and craft-workers enough of the stuff they produced to give the elite a better-than-desperately-poor standard of living, and also allow them, most of the time, to maintain control.

Once people began to farm, especially farm grains, they become relatively stationary: Agriculturalists cannot carry their resources away with them. Their wealth is in their land and the crops they are growing, rather than in their heads and in the tools they carry. Thus farmers cannot run away when thugs-with-spears show up, and demand half their crop.

Before 1870, there was no possibility that humanity could bake an economic pie that was sufficiently large for everyone to potentially have enough. Slow technological progress, the necessity under patriarchy of trying to have more sons in the hope that at least one would survive, and natural resource scarcity—those put mankind under the Malthusian harrow, in dire poverty. Thus most of governance back then, and most social energy back then, was directed at some elite's (a) running a force-and-fraud, exploitation-and-domination machine, (b) elbowing other potential elites out of the way, and then (c) utilizing their ill-gotten gains in building a high culture in which the non-élite were villains and churns. The pressures making for human inequality, and for gross human inequality, were enormous and inescapable.

Thus, for most of recorded human history, history as studied by non-"presentist" historians consisted of this: studying how those who benefited from the operation of the exploitation-and-domination machine cooperated in building and enjoying their high culture and came into conflict within and between civilizations, as they carried out their respective roles as masters, thugs-with-spears (and later thugs-with-gunpowder-weapons), order-giving bureaucrats, record-keeping accountants, and propagandists.

Thus "modes of domination" were as important as modes of production, at least, in the old days. And thus there are four other dimensions of global economic history worth noting at this point—all having to do with inequality and distribution.

The first is the extraction-status dimension: slavery, serfdom, & lesser degrees of status unfreedom.

The second is the general within-society across-household inequality dimension: plutocracy.

The third is the gender dimension: patriarchy

And the fourth is the cross-country inequality dimension: divergence (of national economies).

That humanity was unequal does not mean that the upper class back then was rich. It does not mean that the standard of living of the upper class back in the Agrarian Age would really impress us. They may have been famous. But from our standpoint they were not really rich.

For one thing, life expectancy was short, even for the upper class: 20 to 30 at birth, rather than our 80 or so. Some plague might will get you. And if you were female, childbed might will get you as well. Of British queens, one in seven in the years from 1000 up to 1650 died in childbed. Males escaped childbed mortality, and also by-and-large escaped the extra mortality from nursing sick children with infectious diseases. But if you were male or unlucky and female you faced risks from human violence. 1/3 of English monarchs from William the Conqueror up to 1650 either died in battle, were assassinated, or were murdered after some sham show of judicial process. Probably the risks of violent death at the hands of others were lower for people who were not so eminent. Probably.

For another, lots of things that we think of as nice to have, but not as especially crucial or key or even valuable, were way out of their reach of even the richest during and after the Agrarian age. Suppose you lived in 1610. Suppose you wanted, in your house, to watch a horror movie—strike that, no movies: a horror play—something about witches or devils or such, and wanted to watch it in your house. One person in all the island of Great Britain could do that. If you wanted to do that, you had better be named James I Stuart, you had better be King of England and Scotland, and your acting company had better have either Shakespeare’s MacBeth or Marlowe’s Dr. Faustus in repertory.

And before: If you were Gilgamesh, King of Uruk in the year -3000, What could you do? You could boss people around yes–get the men to build walls and canals and to drill as soldiers, and get the women to serve and service you. You could drink beer—wine and distillation had not yet been invented. You could eat flatbread or porridge. You could eat meat every day—which your subjects could eat only rarely. You could eat honey—which few people could do. And honey was important: do we have any Melissas or Deborahs out there?

You could sit on cushions stuffed with wool.

But, for Gilgamesh, to even get cedar or some other wood for your walls or floors—that required a major military expedition. With associated transport logistics.

Back then, in the Agrarian Age, human technological progress was glacially slow. And here there is a puzzle. For progress and sophistication in the arts, in politics, in religion, in social Organization—ancient Athens even heard its equivalent of keeping up with the Kardashians, only the star was named Phryne and not Kim. But not just in the level of technology but in the pace of technological advance, we moderns far outstrip the ancients in a way that we do not In, say, composing poetry.

Efflorescences and Dark Ages

And even though life back in the Agrarian Age was nasty brutish and short, it was not always the same. There were civilizational efflorescences. They were empires that brought peace and relative prosperity to large chunks of the land. There were also dark ages and barbarian invasions and civilization-shaking catastrophes as well. There was a history of economic growth and decline in the Agrarian Age: it was not all stasis and stagnation. We will consider those next time.

The Late-Antiquity Pause

Changes to the evolution of the human economy begin to emerge after the year 150. But the first change is not, from the standpoint of the potential for human progress, a good one.

Then from 150 or so to 800 it looks like we get a definite downshift: the Late-Antiquity Pause. We do not get a further acceleration to more than 0.06%/year of technology growth. We get a fall to a rate of 0.14%/year, a slower rate of technology growth than humanity had seen since before the start of the Bronze Age. Something goes wrong. There is the crisis of the Antonine Dynasty in the Roman Empire at one end, the collapse of the Han Empire at the other end, shortly followed by the collapse of the Parthian Empire and the Indo-Greek kingdoms under pressure a Sassanians, Kushans, Hephthalites, and others.

Instead of the near-tripling from the year 150 to the year 800 in population that the Axial Age of -1000 to 150 would have led us to expect, human population in 800 is only 20% above population in the year 150. Ideas growth—and population growth—slowed drastically. From 150 to 1500, each person on the globe contributed only 1/8 as much to ideas growth as their axial-age predecessors. And it was still the case that essentially all improvements in technology flowed through to increasing population, with essentially none flowing through to higher labor efficiency, productivity, and living standards for the typical human. The sources of this Late-Antiquity are a substantial mystery, surrounded by speculation, but with little in the way of solid knowledge.

Mediæval Recovery, Technological Breakout, and Dispelling the Ensorcellment of the Devil of Malthus

But things then recover, somewhat: 800 to 1500 see technology growth recover to 0.05%/year. So progress in technological advance does, however, continue. By the year 1500 we have 𝐻 = 0.43. But we also have 500 million humans, compared to the 200 million of year 150 or the 5 million of year -6000. Typical standards of living in 1500? They still seem much the same: still 2.5 dollars a day.

Thereafter come the really big changes. Thereafter comes the breakout:

a growth rate of useful ideas of 0.15% per year during the 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age.

a growth rate of useful ideas of 0.44% per year during the 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution Age.

a growth rate of useful ideas averaging 2.06% per year during the post-1870 Modern Economic Growth Era.

a population explosion, and then a slowdown toward zero population growth as prosperity brings female education, female education brings greater female autonomy, and literate women with rights to own property find that there are other ways to gain and maintain social power than to try as hard as possible to become the mother of many sons and daughters.

From 1500 to 1770 to 1870—over, first, the Imperial-Commercial Revolution and, second, the Industrial Revolution eras—our quantitative index H grows from 0.43 to 0.64 to 1.0. And this time there was some increase in typical standards of living: figure a world in 1870 with $3.5 a day per person, albeit much more unevenly distributed. But, still, the overwhelming bulk of improvements in human technology and organization went to supporting a larger population: the 500 million of 1500 had grown to 1.3 billion by 1870, as better living standards lowered death rates worldwide.

From 1870 to 2020, in our era of Modern Economic Growth, our H has risen from 1 to 27. Our population has risen from 1.3 to 8 billion. And our resources from $3.5 to $32 a day.

From this perspective, there are two big questions in post-Neolithic Revolution global economic history:

Why was there and what determined the pace of the triple accelerations in growth to 0.15% and then 0.44% and now 2.06% per year?

Why was there and what determined the—much, much, much slower—pace of growth of 0.03% per year (with a -1000 to 1 temporary and with a post-800 perhaps permanent jump up) from the -3000 invention of writing to 1500?.