Once people began to farm, especially farm grains, they become relatively stationary: Agriculturalists cannot carry their resources away with them. Their wealth is in their land and the crops they are growing, rather than in their heads and in the tools they carry. Thus farmers cannot run away when thugs-with-spears show up, and demand half their crop.

Before 1870, there was no possibility that humanity could bake an economic pie that was sufficiently large for everyone to potentially have enough. Slow technological progress, the necessity under patriarchy of trying to have more sons in the hope that at least one would survive, and natural resource scarcity—those put mankind under the Malthusian harrow, in dire poverty. Thus most of governance back then, and most social energy back then, was directed at some elite's (a) running a force-and-fraud, exploitation-and-domination machine, (b) elbowing other potential elites out of the way, and then (c) utilizing their ill-gotten gains in building a high culture in which the non-élite were villains and churns. The pressures making for human inequality, and for gross human inequality, were enormous and inescapable.

Thus, for most of recorded human history, history as studied by non-"presentist" historians consisted of this: studying how those who benefited from the operation of the exploitation-and-domination machine cooperated in building and enjoying their high culture and came into conflict within and between civilizations, as they carried out their respective roles as masters, thugs-with-spears (and later thugs-with-gunpowder-weapons), order-giving bureaucrats, record-keeping accountants, and propagandists.

Thus "modes of domination" were as important as modes of production, at least, in the old days. And thus there are four other dimensions of global economic history worth noting at this point—all having to do with inequality and distribution.

The first is the extraction-status dimension: slavery, serfdom, & lesser degrees of status unfreedom.

The second is the general within-society across-household inequality dimension: plutocracy.

The third is the gender dimension: patriarchy

And the fourth is the cross-country inequality dimension: divergence (of national economies).

Slavery, Serfdom, & Lesser Forms of Ascribed Status-Driven Unfreedom

When economists think of inequality, they almost invariably think of it terms of incomes, spending, and prices—all as measured by the yardstick of money and prices, and thus by what goods and services the rich guy can consume or command the use of. An unequal society is one in which those at the bottom get to make use of a small share of society’s resources. It is one in which the work they must do to gain access to that small amount and share is lengthy and burdensome.

Of course all of this is for males of the proper ethnicity—the proper semi- or completely-fictional extended kin-group. They werepretty much the only people who fully counted. Slaves were unequal. Women were unequal. In the United States Amerindians—if they had survived the plagues and the wars and the forced migrations—were unequal. Even among American white men, non-slaveholders in the slave south had very little societal power: If they ran their own farms, they had to sell their produce into a market in which slave-grown corn and slave-raised pigs were determining the prices that they could get. If they sought to work for others, they had to sell their labor into a market in which their potential employers' competitors would be using and driving their slaves with the whip, and thus pushing down the wages that their own employers could afford to pay.

Income and extraction closely interlinked with status…

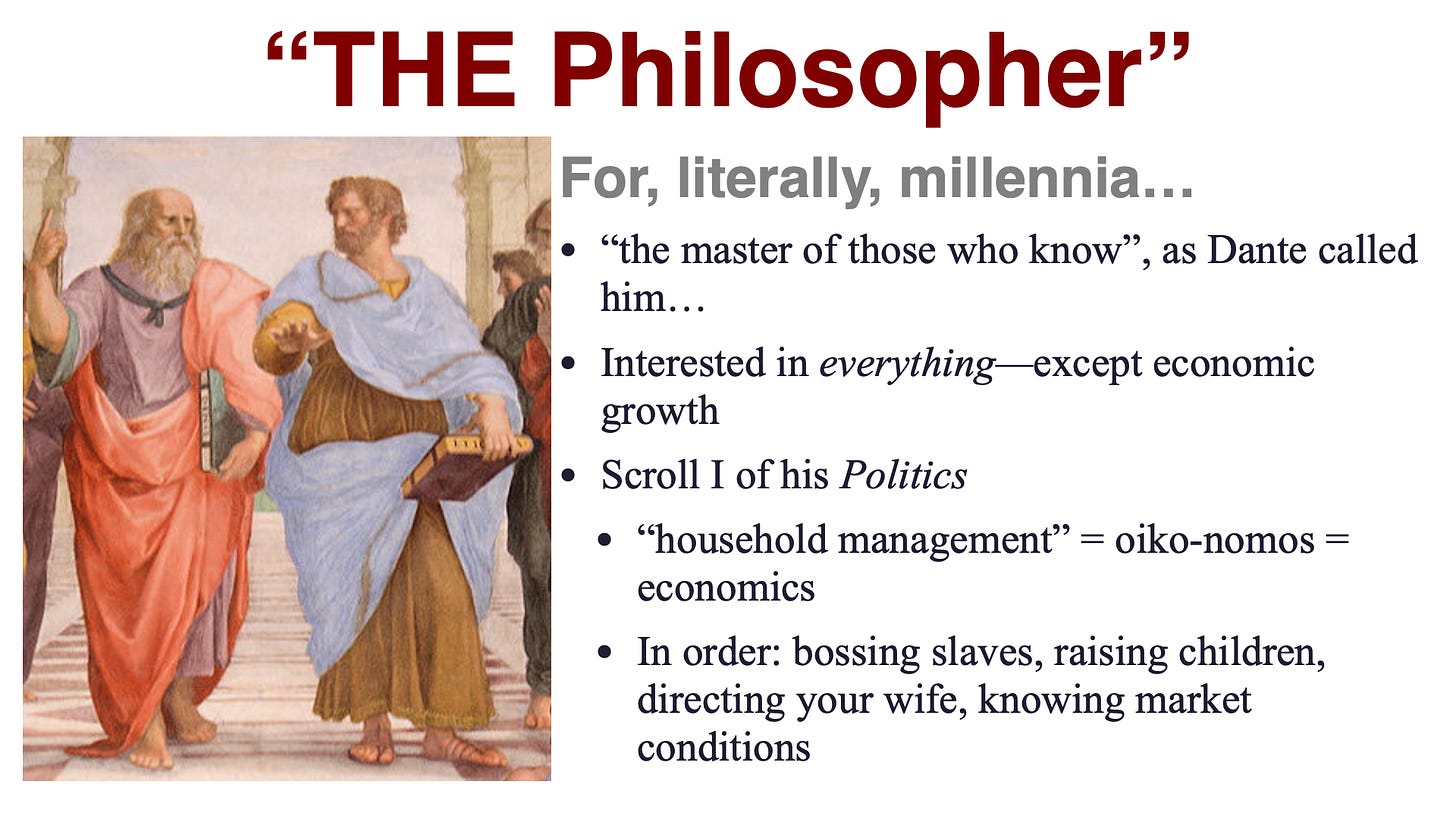

Once again, let us consider Aristoteles of Stageira, sometime tutor of Alexandros III “The Great” Argeádai of Macedon”. For 2000 years, from the moment he became the favored pupil of Plato up until call it the year 1650, and in a long arc from Ireland to India, Aristotle was THE Philosopher. Capital P. THE definite article. If you said “the philosopher”, you were referring to Aristotle. And people did. He was “the master of those who know”, as Florentine poet Dante Alighieri named him.

Aristotle’s main discussion of what we callteconomics comes in the book we call the politics. The Politics is about how prosperous and wealthy Greek men organize themselves and their inferiors into city-states that provide an arena and support for life and, of course, for the practice of philosophy. The first book—actually, for him it was the first scroll—Of the politics is about economics, or rather resources and household management, because unless resources and the households Controlled by prosperous and wealthy Greek men Are present and well organized, successful organization of a city state, of a polity, will be impossible.

In the first book of his Politics, Aristotle talks about the necessity of owning slaves. It is, in fact, The first thing on his mind when he talks about managing resources on the part of the household—Greek oikos, household, and Greek nomos, organization or management. Hence oiko-nomos. Hence economics.

THE Philosopher says:

Let us first speak of master and slave….

No man can live well… [without] necessaries…. The management of a household… [needs] property as instruments for living. And... a slave is living property.… If every tool could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the statues of Daidalos, or the tripods of Hephaistos, which, says the poet Homer, “of their own accord entered the assembly of the Gods”; if, in like manner, the shuttle could weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them, then chief workmen would not need servants, nor masters slaves…

The tripods of Hephaistos are self-propelled catering carts, from Homer’s Iliad:

Thetis of the silver feet came to the house of Hephaistos,

Imperishable, starry, and shining among the immortals,

Built in bronze for himself by the god of the dragging footsteps.

She found him sweating as he turned here and there to his bellows

Busily, since he was working on twenty tripods

Which were to stand against the wall of his strong-founded dwelling.And he had set golden wheels underneath the base of each one

So that of their own motion they could wheel into the immortal

Gathering, and return to his house: a wonder to look at.

These were so far finished, but the elaborate ear handles

Were not yet on. He was forging these, and beating the chains out.

As he was at work on this in his craftsmanship and his cunning,Meanwhile the goddess Thetis the silver-footed drew near him…

But, observed Aristotle, he did not live in such a Golden Age, in which music could be played and cloth woven without human hands. He, Aristotle, did not have robot blacksmiths or the self-propelled serving trays that could both keep the food warm and decide when it should be brought into the dining room, things that myth attributed to the lifestyles of the heroic and divine. Since he did not have these, Aristotle, or any other Greek man who wanted to lead a leisurely enough life to have time to undertake philosophy, and play a proper role in the self-governance of the city-state, needed to own and effectively boss slaves.

And not just one or two slaves either, but household slaves, agricultural slaves, craft work or slaves, and perhaps more.

And also note that, once again, this is income, not status and caste.

It is, throughout human history, very important not to lose sight of status and caste.

Simple income accounts tend to record the United States on the eve of the Civil War as an extraordinarily equal society with its top 1% white non-Amerindian guys having 4-6 times the lifetime income of the average white, male, non-Amerindian.

But there were four million slaves among the 30 million inhabitants of the U.S. in 1860. They had the strongest possible objections to that claim that the U.S. was then significantly less unequal than Britain.

From their perspective—and, I would hope, from ours—the fact that the richest white male non-Amerindian had only 5 rather than the then-European 25 times the lifetime income of the average white male non-Amerindian is not the most important feature of American inequality on the eve of the Civil War. The most important fact is, as Abraham Lincoln said in 1858 at the end of his speech at Ottawa, IL. He was softening his words in order to appeal to the non-abolitionist white male electorate of Illinois. And he said that even though:

I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races…. Inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary…

Nevertheless:

I hold that, notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. [Loud cheers.] I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man. I agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many respects-certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man.

No. The Pre-Civil War United States was not a low inequality society. The coming of emancipation in 1863 and 1865 was a huge thing for economic and social equality. The coming of feminism, even early feminism, was a substantial thing for social equality if not for economic.

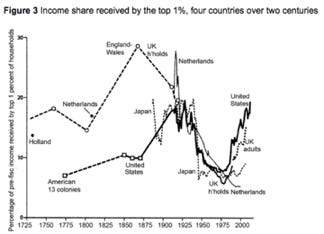

Pre-industrial northwest Europe, by contrast, was a slavery-free but an income-inequality abundant society. The top 1% (of males) at any point in time had 15-20 times the income of the average—figure 10-15 times the lifetime inequality. In both the Netherlands and Britain, figure that at any point in time from 1860 to 1930 the top 1% had incomes 20-30 times the average.

A great deal of inequality, however, is not just work, income, spending, and prices. A great deal is simply things that you are not allowed to do, or are expected and required to do, by virtue of what we might as well call your status-group, your estate, your caste. Minorities. Serfs. Slaves.

This is always present as a background in economic analysis. But this is usually much more than a background factor in human societies. I am not a great fan of those who try to distinguish wealth from freedom—power to command resources from autonomy—positive from negative liberty—in human societies. If you are locked in a cage, it matters a little to you whether you could buy a key if only you had the more money which you do not. So never take a distribution of wealth or income as in any sense a set of sufficient statistics for inequality.

Inequality & Plutocracy

How important?

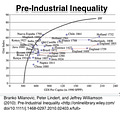

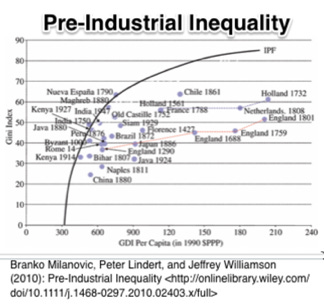

Branko Milanovic, Peter Lindert, and Jeffrey Williamson have estimated some numbers and drawn some graphs about inequality back in the agrarian age—that is, from 8000 B.C.E. to 1750 or so. It looks as though societies were by and large about as unequal as they could possibly be. Paying higher taxes or higher rents or higher tithes than were levied may indeed have meant that large numbers of children would die. Extracting more wealth would not have been an easy thing for an elite comprised of thugs with swords and grifters with fancy sacred headdresses to accomplish.

Our societies have much more headroom, and can sustain much more inequality than they could. Nevertheless, most pre-industrial societies appear to have had inequality nearly as great as could have possibly been sustained.

Starting in 1725 or so we begin to see, for the first time, claims that inequality is actually functional, and makes some sense for society as a whole—rather than natural, and part of the right order of things. We may have seen this once or twice before—Aristotle’s justification of slavery for example. But that the industrious need to be properly incentivized to work hard by the prospect of the coming rich and this becoming rich redounds to the benefit of society as a whole—that is something we first see in full flower in the 18th century. Probably the reason is that it only becomes a question in the 18th century. Before the 18th century there were not enough poor people who could read for inequality to need justification.

The latest historical inequality numbers—even more recent than those of Thomas Piketty—come from Peter Lindert and Jeffrey Williamson. They tell us that America in the 1600s and 1700s in America the top 1% had 8-10 times the average income, rather than the 15-30 times average income found in northwest Europe. Today in the U.S., the top 1%—roughly those households with incomes more than $500K/year—receive (I don’t want to say “earn”) 20 times the average.

Note, however, that the top 1% are overwhelmingly 40 to 60 years old. A significant part—maybe 4%-points?—of the greater income share of the top 1% is simply the age gradient of income. My household dances between the top 1% and the top 2% of the American income distribution. But in 1984 we were at the 25%-ile of the income distribution, living on $5,000 in a studio apartment in Somerville, MA, across the street from a junkyard. Think of the top 1% in colonial America (of male, white, non-Amerindians) as having not 8-10 but 4-6 times average income—and figure their counterparts in the Old World as then having 11-26 times average.

We can clearly see the post-emancipation eras of American history separating into three great inequality waves:

The first Gilded Age: rising inequality in the U.S., slightly falling in Europe.

The age of social democracy, the Great Compression—in these data coming at the start of World War II—and then the 40 years of the-social democratic middle-class society.

The Second Gilded Age: We are now in a second Gilded Age: the shift to which Bega with Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. It has seen our attainment today of previously unseen levels of American inequality <http://voxeu.org/article/american-growth-and-inequality-1700>.

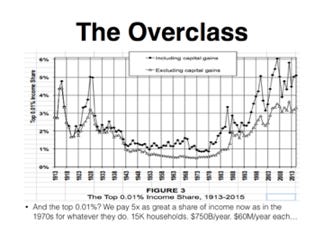

Let me briefly focus on our overclass: the top 0.01%. These are 15,000 households in the United States of America. Their incomes average 60 million a year. Today, we pay five times as much to the overclass for them to perform the services for society that they do. What do the rest of us get in return? And how is it that it is this category of income that has been so greatly amplified in the Second Gilded age: the overclass share is now 2/3 greater than it was even back in the first Gilded Age.

5% of national income for 0.01% of the population means that these 15,000 households collectively have 500 times average income. Back in 1970 their counterparts had only 100 times average income. What has happened to our market economy and our system of property ownership to generate this change?

Briefly, six factors appear to have mattered: education, finance, healthcare financing, the decline of the union movement, unemployment, and technology. Three factors have not: “bad trade deals”, low-education immigration, and affirmative action.

Patriarchy

Agrarian-age patriarchal inequality is literally inscribed in our genes.

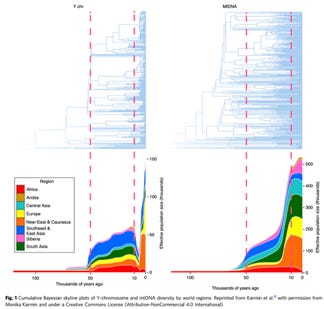

It is an elementary fact of our genetics that there is a small proportion of our genome—the mitochondrial DNA genome—that we inherit only from our mothers. Thus we can trace descent back through the exclusively female line, and by looking at the amount of mutations and genetic divergence in a human population today in that portion of the genome, determine the effective female population size of the human race back in the past all the way back to mitochondrial Eve: the woman who is the mother's mother's mother's... mother's mother's mother of us all. And It is an elementary fact of our genetics that there is a small proportion of every male's genome—the y-chromosome genome—that we inherit only from our fathers. Thus we can trace descent of males back through the exclusively male line, and by looking at the amount of mutations and genetic divergence in a human population today in that portion of the genome, determine the effective male population size of the human race back in the past all the way back to y-chromosome Adam: the father who is our father's father's father's... father's father's father of us all.

When we do this, we find something going on between the years -8000 and -2000. The effective female population size becomes much much much much larger than the effective male population size in that era. Lots of mitochondrial lineages are coming down to us: women are having daughters who have daughters... whose daughters' daughters' daughters are among us. A much smaller number of y-chromosome lineages are being evolved and then surviving—perhaps 1/20 as large. This would seem to mean that 10000 to 2000 years ago something exterminated most of the y-chromosome lineages. saw substantial polygyny for a few men, and non-reproduction for others. It also means the inheritance of male reproductive advantage: that if your great-grandfather had the resources to have more than one wife, the odds were higher that you were at the top of the inequality pyramid and had the resources more than one wife as well. Patriarchal reproductive inequality was in that age both substantial and inherited.

This is polygyny: one man, many wives—and lots of men with no wives and little sexual access to women. This is the Biblical Patriarch Jacob: 13 children with two wives and two concubines. Jacob and Leah's children were Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah Issachar, Zebulun, and Dina; Jacob and Rachel's children were Joseph and Benjamin; Jacob and Zilpah's children were Gad and Asher, and Jacob and Bilhah's children were Dan and Naphtali. And somewhere in the neighborhood there were three men—unnamed—who were without wives, and without children. Leah, Rachel, Zilpah, and Bilhah's mitochondrial DNA lineages were passed down. The three nameless men's y-chromosome lineages were not: only Jacob's was.

Maintaining polygyny for a number of generations requires great social pressure and great societal inequality among men. It also requires a great deal of subservience among women. What was human life and human inequality like back in this patriarchal age? What brought it on? What made it come to an end?

In 1764, in Britain’s Massachusetts colony, Abigail Smith was 20. She had had no formal education at all: girls weren’t worth it. She married a man she had known for five years: the up-and-coming 30-year-old lawyer John Adams, future President of the United States. Children rapidly followed their marriage: Nabby (1765), John Quincy (1767), Suky (1768, died at 2), Charles (1770, died at 10), Thomas (1772), probably a miscarriage or two or three from 1774-6, then Elizabeth (1777, stillborn), then (perhaps) another miscarriage—but I suspect not. She spent five years pregnant. She was rich enough that she, probably, hired a wet-nurse for her children, but somebody or somebodies nursed her children for perhaps fourteen more years: some woman or women were thus eating for two for more than a full decade to raise the next generation of Adamses. In 1776 she writes a famous letter to her husband in which she begged him to write laws providing women with legal personality in the new revolutionary country he was building:

Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable…. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands…. Such of you as wish to be happy willingly give up the harsh title of Master for the more tender and endearing one of Friend. Why then, not put it out of the power of the vicious and the Lawless to use us with cruelty and indignity with impunity?… Regard us then as Beings placed by providence under your protection and in immitation of the Supreem Being make use of that power only for our happiness…

Her husband John Adams thought this was a great joke:

I cannot but laugh…. Your letter was the first intimation that another tribe, more numerous and powerful than all the rest, were grown discontented. This is rather too coarse a compliment, but you are so saucy, I won't blot it out. Depend upon it, we know better than to repeal our masculine systems…. We have only the name of masters, and rather than give up this, which would completely subject us to the despotism of the petticoat, I hope General Washington and all our brave heroes would fight…

Read the letter entire <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0241>.

Why male supremacy was so firmly established is something that is not obvious to me. Yes, it was very important to have surviving descendants. Yes, attaining a reasonable chance of having surviving descendants to take care of one in one’s old age meant that the typical woman spent 20 years eating for two: pregnant and breastfeeding. Yes, eating for two is an enormous energy drain, especially in populations near subsistence. Yes, prolonged breastfeeding was a substantial mobility drain kept women very close to their children, and impelled a concentration of female labor on activities that made that easy: gardening and other forms of within-and-near-the-dwelling labor, especially textiles. Yes, there were benefits to men as a group from oppressing women—especially if women could be convinced that they deserved it:

Unto the woman he said, ‘I will greatly multiply thy sorrow and thy conception; in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband; and he shall rule over thee’…

But surely women as equal participants in society, rather than just chattels, classified as a little bit above slaves and cattle, can do a lot. We—optimistic—economists have a strong bias toward believing that people in groups will find ways to become, collectively, more productive and then to distribute the fruits of higher productivity in a way that makes such a more productive social order sustainable. But apparently not.

The bio-demographic underpinnings of the cultural pattern of high male supremacy began to erode even before 1870. But it was over 1870-2016 that these underpinnings dissolved. Reductions in infant mortality, the advancing average age of marriage, and the increasing costs of child raising together drove a decrease in fertility. The number of years the typical woman spent eating for two fell from twenty—if she survived her childbed—down to four, as better sanitation, much better nutrition, and more knowledge about disease made many pregnancies less necessary for leaving surviving descendants, and as birth control technology made it easier to plan families. And, after exploding in the Industrial Age, the rate of population growth in the industrial core slowed drastically. The population explosion turned out to be a relatively short-run thing. Human population growth rapidly headed for zero long-run population growth.

The path of within-the-household technological advance also worked to the benefit of the typical woman over 1870-2016: dishwashers, dryers, vacuum cleaners, improved chemical cleansing products, other electrical and natural gas appliances, and so on, especially clothes-washing machines—all these made the tasks of keeping the household clean, ordered, and functioning much easier. Maintaining a nineteenth-century, high-fertility household was a much more than full-time job. Maintaining a late twentieth-century household could become more like a part-time job. And so much female labor that had been tied to full-time work within the household because of the backward state of household technology became a reserve that could now be used for other purposes. And, as Betty Friedan wrote in the early 1960s, women who sought something like equal status could find it only if they found “identity…in work… for which, usually, our society pays.” As long as women were confined to separate, domestic, occupations which the market did not reward with cash, it was easy for men to denigrate and minimize.

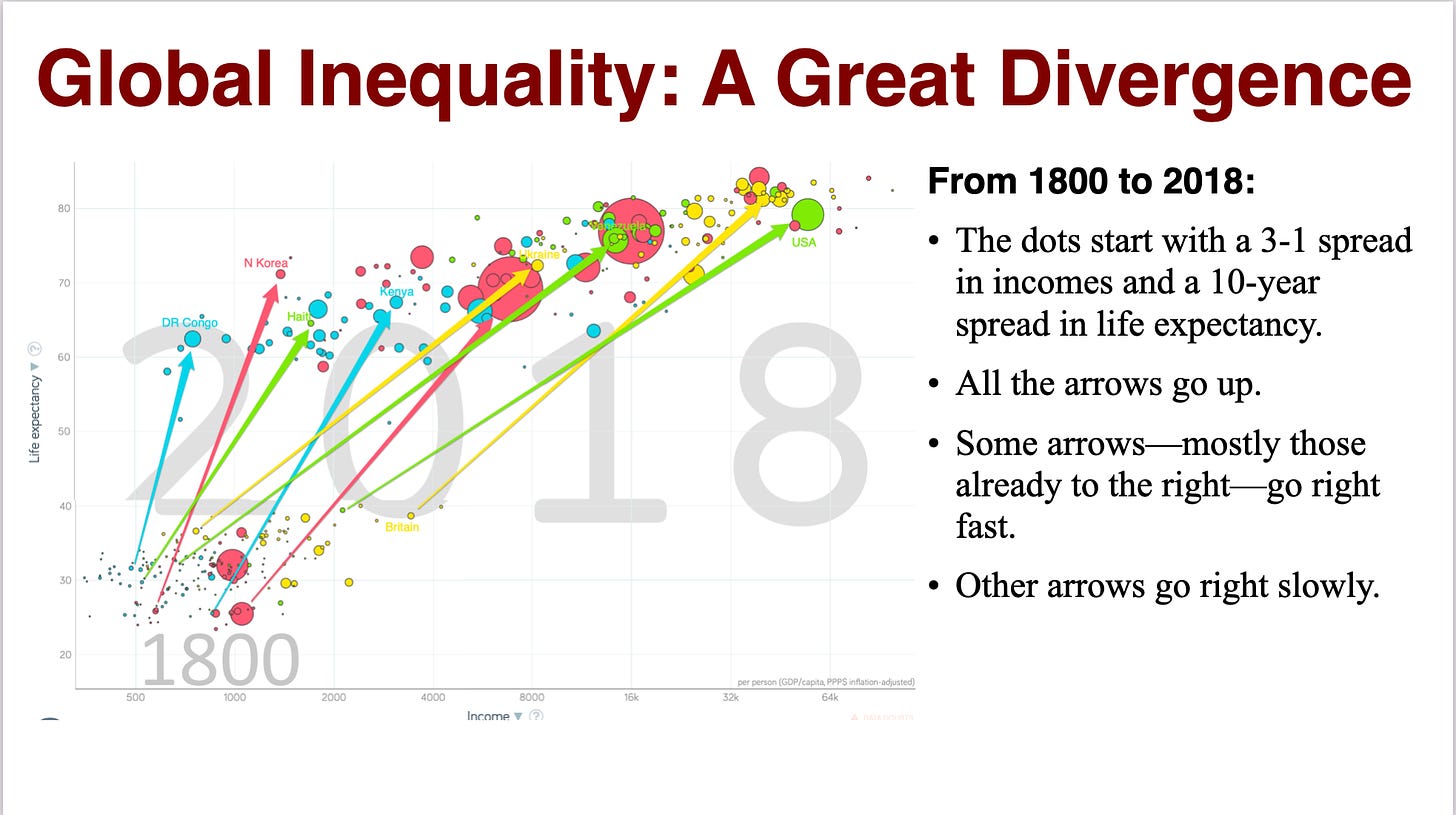

Global Divergence

In 1870, when the long twentieth century began, British industry stood at the leading edge of economic and technological progress, and the world’s real income per capita had reached perhaps $6,000 a year. However, that was already at least double what was found anywhere outside the 400-mile radius charmed circle centered on the British port of Dover, plus Britain’s overseas settler colonies, and the United States, its ex-colony. Outside this nascent global north, our standard estimates show annual income per capita levels with a spread of a factor of five, ranging from $600 in the poorer parts of Africa to $3,000 in those European economies about to join the global north. The curve is heavily weighted toward the lower end, because China and India were then in the down-phase of the Malthusian cycle. The average per capita annual income level within the global south alone was perhaps $1,300.

By 1911 the world had grown—largely together. Global-south incomes were now spread by a factor of almost six, ranging from $700 to $4,000—with Russia, fueled by French loan capital to build its railways, in the lead. The global-south center of gravity had inched up to perhaps $1,500. But the Global North had forged ahead too.

What happened then was strikingly at variance with the expectations of neoclassical, neoliberal, and neoliberal-adjacent economists like myself, who hold that discovery is—or should be—more difficult than development, that development is more difficult than deployment, and so that the world economy should “converge” over time. Between 1911 and 1990 that did not happen. The opposite did: the world economy diverged to a stunning degree. The economies of the Global South did not catch up to, or even keep pace with, the fast-runners of economic growth and development.

The global south did grow, by and large. But it did not catch up. Latin America lost a decade of development in the 1980s. As of the early 2020s, Chile and Panama are the only Latin American countries that are better off than China, while Mexico, Costa Rica, and Brazil are China’s rough equals. In Africa, only Botswana. In Asia, only Japan, the Four Tigers—South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore—Malaysia, and Thailand. The gap between China and the global north is still a factor of about 3.5 to 1. It was not all disappointing: progress in education and health was rapid and extremely heartening. But that did not hide the disappointing growth in material production.

And Africa has fallen way, way behind: South Africa, Kenya, Zambia, Ghana, and Nigeria—all those for which in the 1960s there were great expectations for economic development—have fallen well short of their promise.

In 1950, more than half the world’s population still lived in extreme poverty: at the living standard of our typical pre-industrial ancestors. By 1990 it was down to a quarter. By 2010 it would be less than 12 percent. And in 1950, most of this extreme poverty was spread throughout the global south. Thereafter it would become concentrated in Africa, where, by 2010, some three-fifths of the world’s extreme poor would reside. This concentration came as a surprise: there had been few signs back in the late colonial days of palm oil, groundnuts, cotton, and cocoa exports—the days when Zambia was more industrialized than, and almost as rich as, Portugal—that Africa south of the Sahara would fall further and further behind, and not just behind the global north, but behind the rest of the global south as well. Thinkers like Nathan Nunn grappled with this data and concluded that this retardation had something to do with the massive slave trades that had afflicted Africa in previous years.

The first post-colonial African head of government to have been assassinated was Nigerian prime minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa. He had been born in the north of the British colony of Nigeria in 1912 and had been sent to boarding school at Katsina College. There, he was student number 145, to be slotted into the imperial bureaucracy as a teacher of English. He did very well. By 1941 he was a headmaster. In 1944 he was sent to University College London, to be trained to become a schools inspector for the colonial administration.

But earlier, back when he was twenty-two, in 1934, a colonial official named Rupert East had commissioned five novellas, to be written in Hausa, in an attempt to spread literacy. In his short novel Shaihu Umar (Wise Umar), the protagonist’s students distract him from teaching them the Quran by asking him how he came to be a teacher. The story that follows is of his enslavement and its consequences: large-scale slave raids, kidnappings, adoptions by childless slavers, and more kidnappings. The protagonist finally meets up with his mother (she has been kidnapped and enslaved too, by the guards she had hired) in Tripoli. She sees that he is pious and prosperous, and then she promptly dies. The vibe is that “people really will do terrible things for money”—and not for large amounts of money either—and that “the world is a Hobbesian war of all against all, but if you read the Quran really well, then you’ll probably prosper, maybe.”

In January 1966 he was murdered in the military coup led by the Young Majors—Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu and company—whose troops slaughtered senior politicians and their generals and their wives, and then were themselves suppressed by a countercoup led by army commander Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi. Aguiyi-Ironsi was assassinated six months later in a July counter-countercoup led by Yakuba Gowon. A year later the Igbo people declared the independent republic of Biafra, which was suppressed after a three-year war causing some 4 million deaths (out of a population of about 55 million), the overwhelming majority of them Igbo dead of starvation. Yakuba Gowon was overthrown by Murtala Muhammed in July 1975. And Murtala was then assassinated in February 19. A return to civilian rule in 1979 lasted only until 1983, when the next military coup took place in Nigeria.