FOR PAYING SUBSCRIBERS: DeLongTODAY: From þe Development of Agriculture to Modern Economic Growth...

Video, script, & c., for my 2021-02-26 Fr DeLongTODAY Leigh Bureau video briefing...

<https://drive.google.com/file/d/1tNEi_bMBqkzyGv9wWqUaPJoZFE1O71Xy/view?usp=sharing>

This is the DeLongTODAY Briefing.

I am Brad DeLong, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and a sometime Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury. This is the weekly DeLongToday briefing. Here I hold forth on the Leigh Bureau’s vimeo platform on my guesses as to what I think you most need to know about what our economy is doing to us right now.

I promised Wes Neff, when he agreed to provide the infrastructure for this, that I and my briefings would be: lively, interesting, curious, thoughtful, and relatively brief.

Relatively.

I promised I would provide briefings on a mix of: forecasting, politics, macroeconomic analysis, history, and political economy…

Today is an economic history briefing. How should we understand, from the most Olympian perspective—indeed, from a super-Olympian perspective—the process of economic growth that the human race has undergone, that humanity has undertaken?

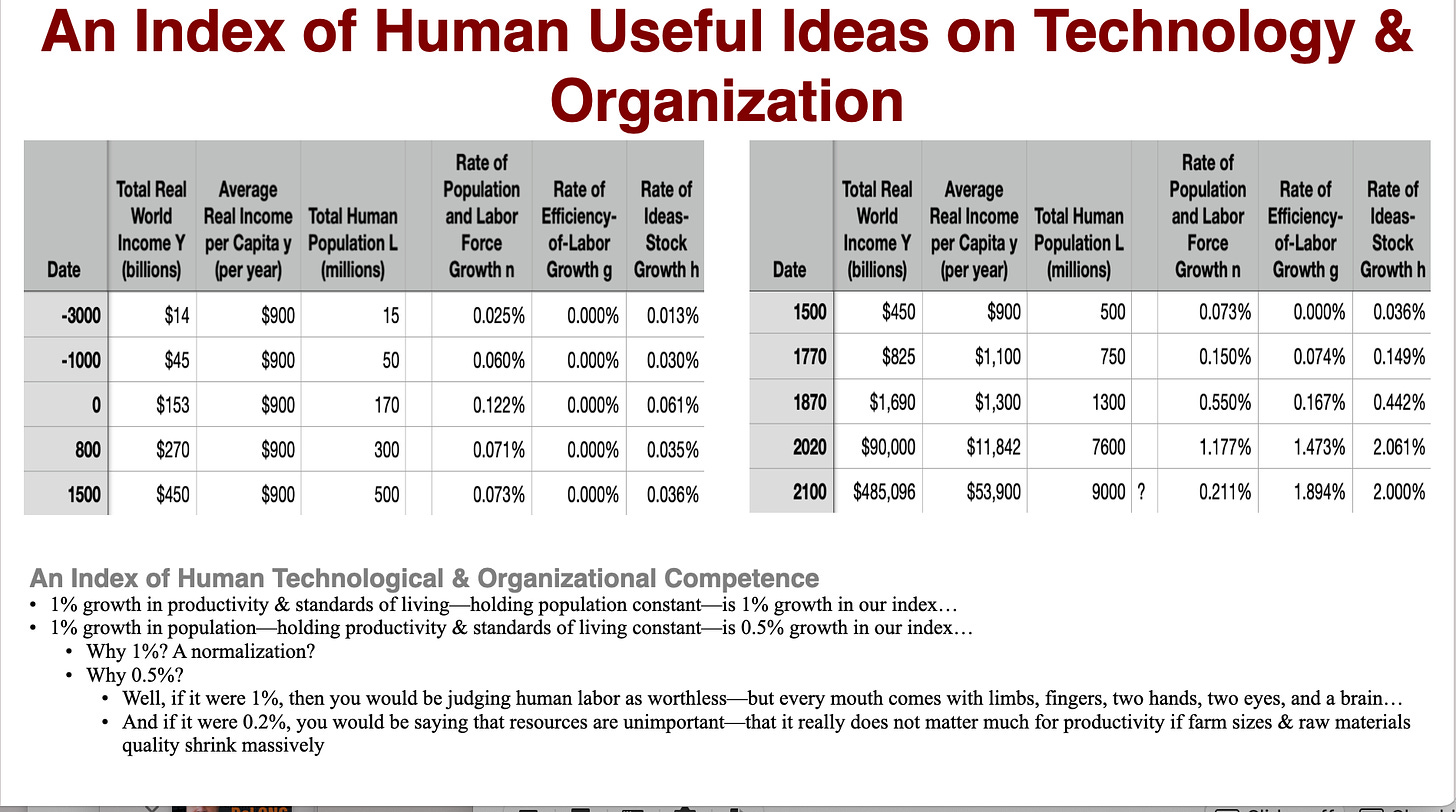

To get a sense, roughly, of magnitudes of the human economic growth process, we start by constructing an index. The index will be of the value of the stock of useful ideas about manipulating nature and organizing humans that have been discovered, invented, and deployed over the globe. We will at the rate of growth of that index.

We set that index so that a 1% increase in real productivity and standards of living, holding human population constant, is a 1% increase in the index.

Why 1%? Think of that as a normalization: other things equal, we would like to say that a society twice as rich without differences in resources per capita or per worker must have twice the value of the stock of useful ideas.

We also set that index so that a 1% increase in population, holding productivity and living standards constant, is a 1/2% increase in the index.

Why 1/2? Well, if it were 1, then you would be judging that human labor is worthless—the same increase in ideas is necessary to support 1% more of a population at the same standard of living as to support the same population at a 1% more standard of living.

That could not possibly be right. Each mouth comes with four limbs, 10 fingers, two eyes, and a brain attached. And if it were a number much smaller than 1/2, say 1/5, then you would be judging that natural resources are unimportant—that it really does not matter much for output per worker if farm sizes are much smaller. And that, also, cannot be right. That cannot be right either in the past in which we were mostly farmers or even in the late 20th century when we got to see how much the global economy depended on cheap oil.

Now let us look at the growth rate of our index:

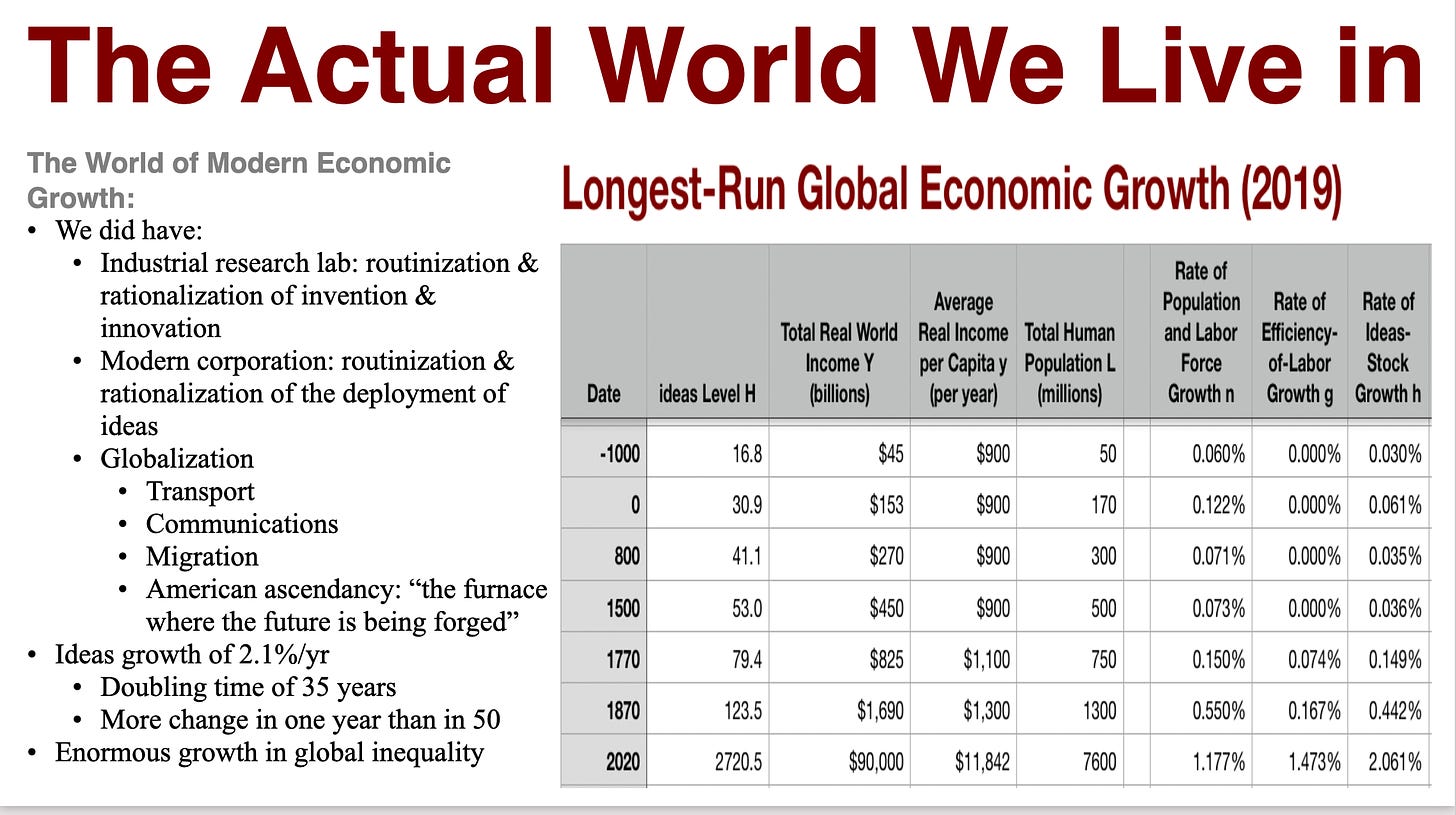

We estimate pretty well that right now the human population is about 7.6 billion, with a total world real income of perhaps $90 trillion a year. Average real income per capita today is just a hair under $12,000 per year. We are confident that a century and a half ago, back in 1870, the total human population was only 1.3 billion. And we are also semi-confident that the average real income per capita was no more than $1300 a year.

(Why “semi-confident”? Because there are grave conceptual difficulties involved in calculating such a number. So much of what we produce today they could not produce at any price. $1300 is about the value today of what they did produce, but if we had $1300 a day we would spend a large chunk of it on things they could not produce at all. And these numbers make no allowance for that.)

From $1300 150 years ago to a hair under $12,000 today—that is a rate of productivity, a rate of efficiency-of-labor, growth of 1.5%/year. From 1.3 to 7.6 billion is a rate of population and labor-force growth of 1.2%/year. Add the first to half the second, and get a growth rate over the past century and a half of 2.06%/year for the value of the stock of human ideas.

(Parenthetically, what is the future likely to bring? We can see from the demographic transition that the world is like to stabilize at a population of 9 billion in this century. As a baseline case, suppose we can maintain our pace of ideas growth for another century. Then the world in 2100 would have an average real income per capita not $12,000 but more than $50,000 per year. The typical human would then have a lifestyle equivalent to that seen in the global north today. And the world would be, in this aspect at least, for the first time a truly human world.)

Now look back before 1870. A century earlier, in 1770, we estimate that the total human population was about 750 million. We know that part of the world that was to become the global north experienced substantial—but not overwhelming—growth in living standards and productivity. We think the world outside the charmed circle of the part most affected by the British Industrial Revolution saw little progress in income per capita, although it did see substantial population growth. Taking the appropriate average gives us a growth rate of 0.17%/year for efficiency-of-labor growth over the British Industrial Revolution century 1770-1870, and of 0.55%/year in population. Add the first to half the second, and get an 0.45%/year for the proportional growth rate of the ideas stock—less than ¼ as much as we have been used to for the past 150 years.

Before 1770, we see the Commercial-Imperial Age stretching back to 1500: an age of globalization in commerce but also in conquest and empire. We see a world of 500 million people in 1500. We see a poorer world in 1500 than in 1770, but not that much poorer. After all, it could not have been much poorer. A world of $900/year—$2.50 cents a day—is a world in which, people must spend ⅗ of their resources simply on their 2000 calories plus essential nutrients a day to survive. Such people find that how hard they can work greatly limited by their biological enemy budget, find that their children’s immune systems compromised by malnutrition. find that their children are stunted so that they are some 4” shorter in height than we are, and so forth. If the human population had been any poorer, it would not have been able to reproduce itself. But it did, and it grew. But it could not have been much richer: it barely gew.

Between 1500 and 1770, our rate of growth of efficiency-of-labor is 0.075%/year. Our guesstimate at the rate of growth of population is 0.15%/year. The first plus half the second gives us 0.15%/year for the rate of growth of the ideas stock—⅓ the pace of the British Industrial Revolution 1770-1870 century, and 1/13 the pace of the past Modern Economic Growth century-and-a-half that we are used to.

And before 1500?

Humanity could not have been materially poorer than $2.50/day. But it could not have been much richer either. In a pre-industrial world with enormous infant mortality, parents are eager for more children in the hope that one, at least, will survive to carry on the lineage and care for them in their old age. We know that a nutritionally-unstressed population without access to artificial means of birth control quadruples in a century—a natural-increase growth rate of 1.5%/year. But when we look back at rates of population growth worldwide, we guess at 0.075%/year from 800 to 1500 and from the year 1 to 800, at 0.12%/year from -1000 to the year 1, at 0.06%/year from -3000 to -1000, and at 0.025%/year for the 3000 years before -3000.

Malthusian near-subsistence effective stasis at $2.50/day—the standard of living of today’s bottom billion. Ferocious infant, disease, and famine mortality reducing average rates of population growth to about 2% per generation. That appears to have been humanity’s lot from the invention of writing and the first stirrings of the Bronze Age in -3000 up to 1500. That gives us a -3000 to 1500 rate of ideas growth of a hair under 0.04%/year: 1/50 as fast as we have seen in our day. In our day, for the past 150 years, we have seen two years produce more proportional invention, discovery, and ideas deployment than a typical century before 1500. And we have seen this even though all the low-hanging-fruit has long been picked, and even though we know so much more that a great deal more discovery and deployment is needed to maintain the same proportional growth rate in the value of the useful-ideas stock.

Gazing down at this picture from a super-Olympian height, I, at least, see five important watershed-crossings in the economic history of the past 5000 years.

The first watershed-crossing is the invention of writing about 5000 years ago. Before then, humans were indeed anthology intelligences—what one person knew, as soon pretty much everyone in the band knew, because of our incredible and sometimes regrettable compulsion to talk and gossip even when we know it will not be a to our long-run advantage. But we were only limited anthology intelligences, because our knowledge was limited and evanescent: what one band knew had a hard time diffusing over great distances; what was not immediately useful could and did decay and be lost over the centuries.

Once we have writing, we are a global time binding anthology intelligence indeed. And that mattered.

We can see that mattering in what happened from year -3000 to -1. More people chattering and communicating leading to more advances in ideas which supported faster population growth from Malthusian forces which produced a greater human population base which produced more chattering and communicating and even more advances and ideas. We have an ideas growth rate that more than doubled comparing before -3000 to after,. And it doubled again comparing before -1000 to after.

But then came the second watershed: the Late-Antiquity Pause.

Comparing before the year 1 to after, we do not see another doubling. Instead, after 170… things fall apart. Dark Ages. Imperial decline and fall. Barbarian invasions. Emperors making unwise political deals with barbarian warlords with names like Alaric the Visigoth and An Lushan the Sogdian. Rather than a breakthrough out of Malthusian near-stagnation, in the years from 1 to 1500 I see a decline in the ideas growth rate, back to 0.035% per year.

There is a breakthrough, however. It comes with the third watershed-crossing, around 1500. The years after 1500, as 1500-1770 sees the Commercial-Imperial Age and its quadrupling of ideas growth over the previous Agrarian-Age norm. Then comes the fourth British Industrial Revolution watershed-crossing around 1770. And then the fifth final watershed-crossing into our Modern Economic Growth era around 1870.

What was it stake in these last three watershed crossings?

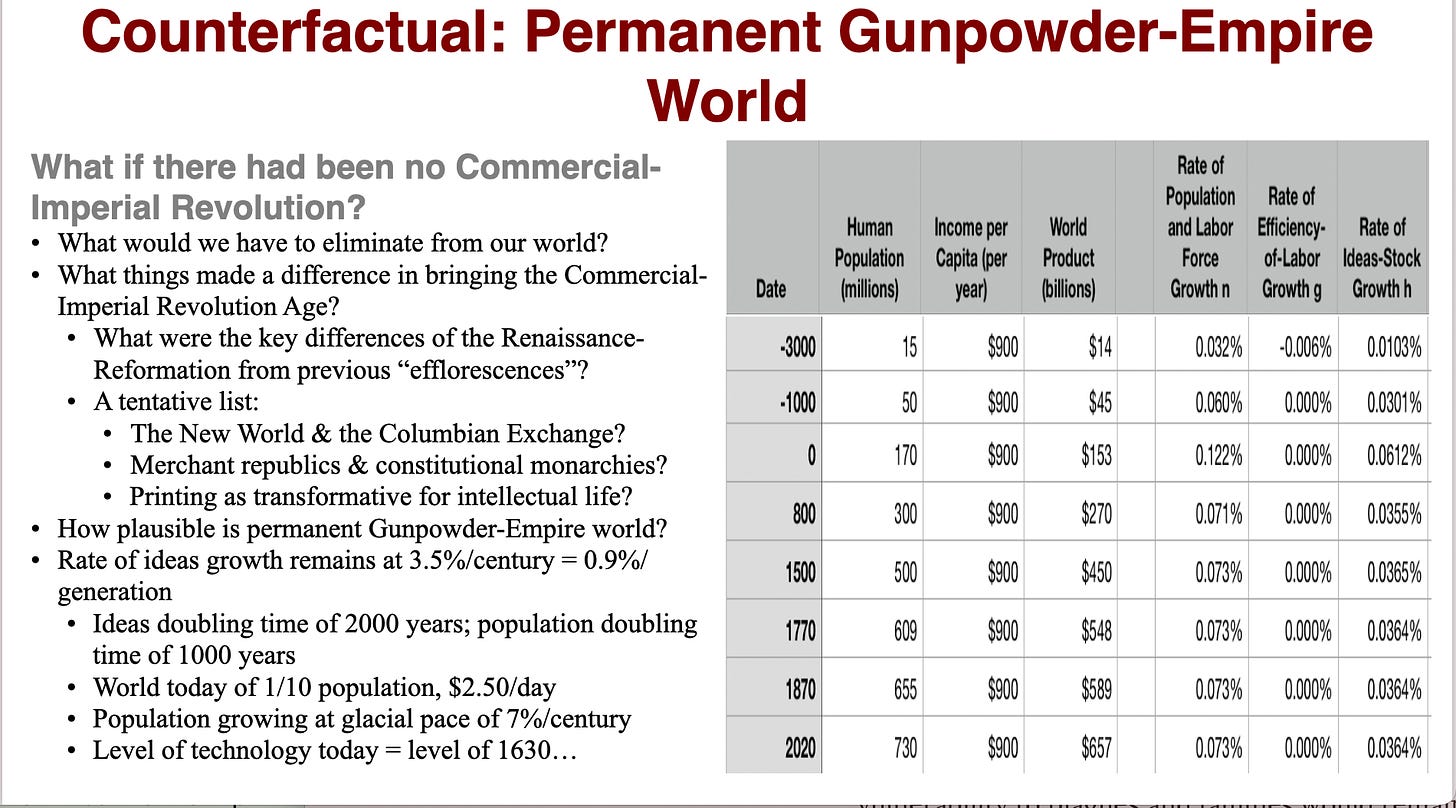

Well, suppose we had not had the coming of the Commercial-Imperial Age after 1500—suppose the pace of ideas growth had remained after 1500 at the worldwide average pace that it had settled at in the previous seven centuries between then and the defeat of the An-Shi rebellion in China and the crowning of Charlemagne in Italy? What would the world now look like?

We can do the arithmetic. the world would stay in Malthusian poverty: figure $2.50/day as the standard of living of the typical human. Infant mortality and vulnerability to plagues and famines would remain, curbing population growth to 7%/century. Today’s world would then, in this counterfactual, have 730 million people on it—about the population of 1700—with a technology level of roughly that of 1630: caravels, muskets and pikes, forward-looking agriculturalists experimenting with nitrogen fixation to replenish soil quality. A world of gunpowder empires and kingdoms, in which each century still looked very much like the previous one.

What would we have had to eliminate from our history in order for there not to have been a Commercial-Imperial Revolution around 1500—in order for there not to have been a quadrupling of the pace of ideas growth come 1500? That is an interesting and deep question. There had been “efflorescences” before. And there had been the axial age, in the millennium before the year 1—or probably better dated -800 to 170—during which technological progress was twice with it had been before and at least half again what it was at the agrarian-age norm. Particularly forms of intellectual curiosity centered around the idea that nature was understandable and mechanical because the spirits were hidden and withdrawn from the world, the widespread distribution of printing as an intellectual progress force multiplier, societal structures in which merchants and clerics had more and princes and warriors less power, an unusual degree of durable non-family frameworks for societal organization, laws that constrained the powerful to some extent rather than just commanding the powerless, a relatively rich society for an agrarian age as a result of patterns of delayed marriage that had grown up in the aftermath of the depopulation of the black death, plus the Columbian exchange, the revolution in bio technology from the transfer of Old-World crops to the New World and New-World crops back to the Old World—always have advocates, and learned and thoughtful advocates. Plus there is the possibility that what was to call it self "Western civilization" was uniquely barbarous, via its patterns of religion, trade, conquest, domination, and enslavement, and that made it uniquely vicious and effective in engrossing resources and commanding people from elsewhere.

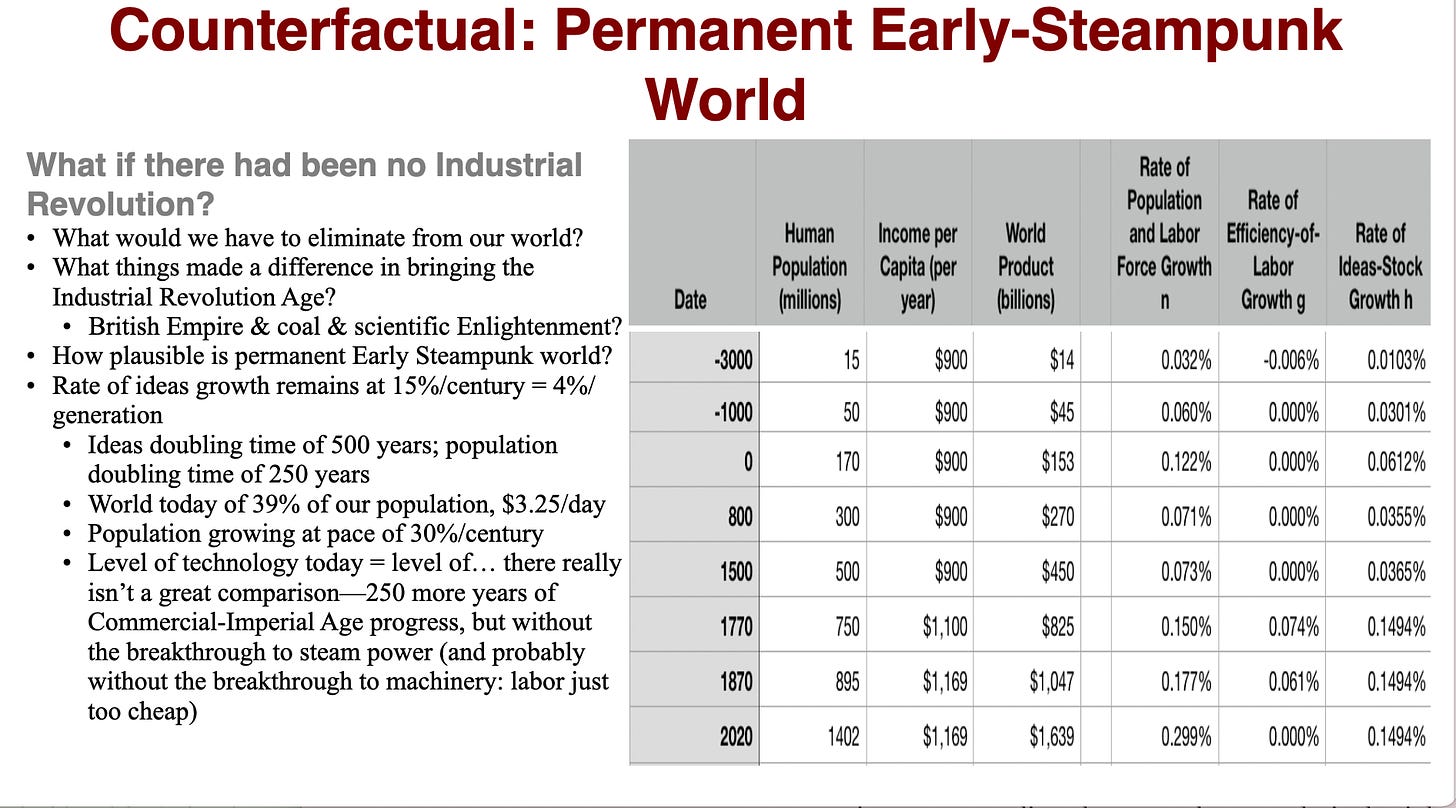

However the transition to the Commercial-Imperial Age of 1500-1770 came about, the pace of ideas growth during it—although four times as fast as the agrarian-age norm—was still only 1/13 of the pace we have grown used to in our Modern Economic Growth Age. If there had not been the breakthrough with the coming of the British Industrial Revolution Age to an even faster rate of growth, what would the world look like today?

Once again, we can do the math: a Commercial-Imperial Age 15%/century pace of ideas growth would have allowed for a 30%/century pace of population growth—roughly 9% per generation. That would not have been sustainable in our $2.50/day Malthusian world. Figure a typical standard of living of noticeably more, $3.25/day or so, for more robust childhood immune systems and for more reliable female ovulation in order to support that rate of average population growth. That is still a world much too poor to trigger anything like a demographic transition: mortality would still be much too high for people to count on their children’s surviving, and to begin to think about how they should try to have fewer children and give more of a leg up in life to those they have.

That world would have a population doubling time of 250 years—and an ideas value doubling time of 500 years. Today’s world would, in this counterfactual, still seem to us like a much emptier world: 1.4 rather than 7.6 billion.

What would technology have been like? 250 more years of Commercial-Industrial technology growth would have given us the technologies of 1830 or so, but with steam engines and textile machines curiosities rather than rapidly expanding sectors of investment and technological deployment. Labor would have simply been too cheap for it to have been worth anyone’s while to invest in improving technologies of steam and automatic machinery to make them truly efficient. Technologies for controlling very cheap labor, on the other hand, would have promised bonanza profits for entrepreneurs. But it is not at all clear to me what forms such technologies would take.

But it turns out that the coming of the British Industrial Revolution—steampower and automatic machinery—was, actually, not decisive for humanity. At least, not if one takes the essence of the British Industrial Revolution to have been the speeding-up of the rate of ideas growth from 0.15%/year to 0.45%/year.

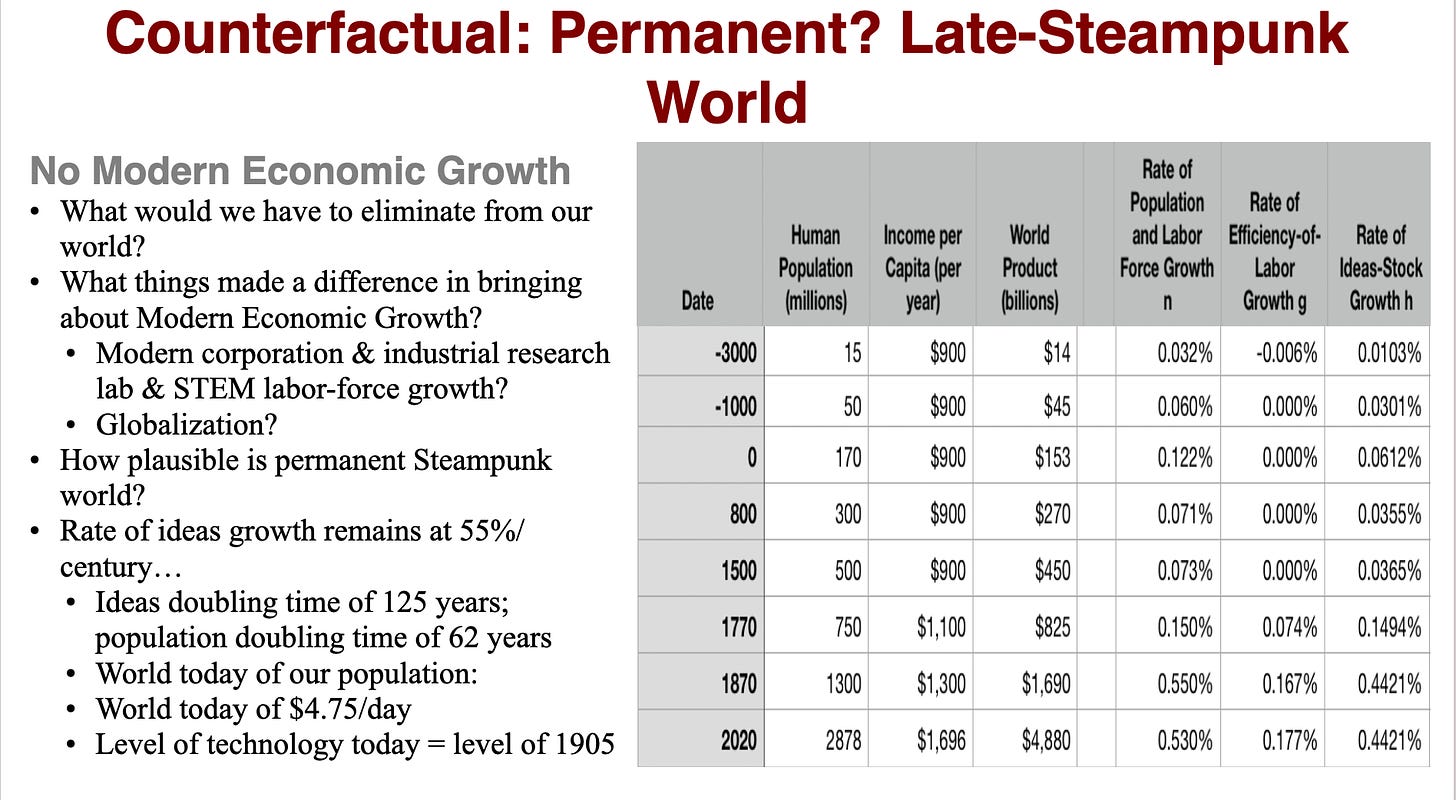

Suppose that the world had kept at its 1770-1870 ideas-stock value proportional growth rate of 0.45%/year since. What then would hte world look like today?

0.44%/year ideas growth can be eaten away by 0.88%/year population growth—that’s 22% population growth per generation: 2 typical parents have 2.4 children survive to reproduce. $2.50/day people are too nutritionally stressed to manage that. $3.25/day people are too nutritionally stressed. But a typical person living on $4.67/day can manage that amount of fertility and child survival on average. And that standard of living and degree of child survival is not enough to trigger any demographic transition. Where 2 children would have survived to grow up and reproduce in a Malthusian Age, there are now 2.4. That does not provide enough security and confidence to lead people to begin thinking about curbing their fertility in order to give a stronger leg-up to their existing children.

Hence a world with ideas growth at its British Industrial Revolution Age pace would head for a stable income level of $4.67/day—$1700/year. Such a world today would have achieved 2.9 billion in terms of the number of people. And the level of technology in such a world would be about that of 1905. But, actually, 1905 had only ⅔ that number of people, and so was already considerably richer by about ⅕ than this Late-Steampunk world we would have today had the 0.45%/year pace of ideas growth continued.

Would such a growth equilibrium have been stable? I strongly suspect not. To get us to today’s level of technology with 0.45%/year ideas growth would take this counterfactual world until 2500. And at that point, with a populaiton doubling time of 62 years, the world would have a population of 500 billion: 70 people where there is, today in our history, every one person. Agriculture would have to be extremely labor-intensive in such a counterfactual—if feeding so many people with our current technology were possible at all. My bet is that something else would have happened: either a breakthrough to Modern Economic Growth, a China one-child policy style demographic transition, or a fall back to Malthusian near-stagation rates of ideas growth.

Of course, these are, none of them, the world we live in.

We did have the third watershed: the Commercial-Imperial Revolution. We do not have a world of gunpowder empires and 1630-era technology with 730 million people. 1/10 our actual population, spread over the world, with the typical human living on $2.50/day. We did have the fourth watershed: the British Industrial Revolution. We do not have a world of 1.4 billion people, ⅕ of our current population, living on $3.25/day. We do not have early-steampunk 1830-technology, but with a great deal more technological ingenuity devoted to labor control and less devoted to boosting labor productivity via steampower and automatic machinery. We do not have late-steampunk 1905-technology, with 2.8 billion people living on $4.67 day, and again with our technology focused on how the elite can marshal and control cheap workers rather than boost their productivity via machines and power sources.

Instead, we have our world: 7.6 billion people with an income level averaging $12 thousand a year—$30/day.

We did have the industrial research lab, with its routinization & rationalization of invention & innovation. We did have the modern corporation, with its routinization & rationalization of the deployment of ideas. We did have globalization as we know it—in transport, in communications, and in migration. We have had American ascendancy: North America as, in Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky’s words, “the furnace where the future is being forged”. We have had for a century and a half and we have grown used to ideas growth of 2.1%/yr—a doubling time of 35 years. We have grown used to more change and development in two years, proportionately, than in a typical agrarian-age century.

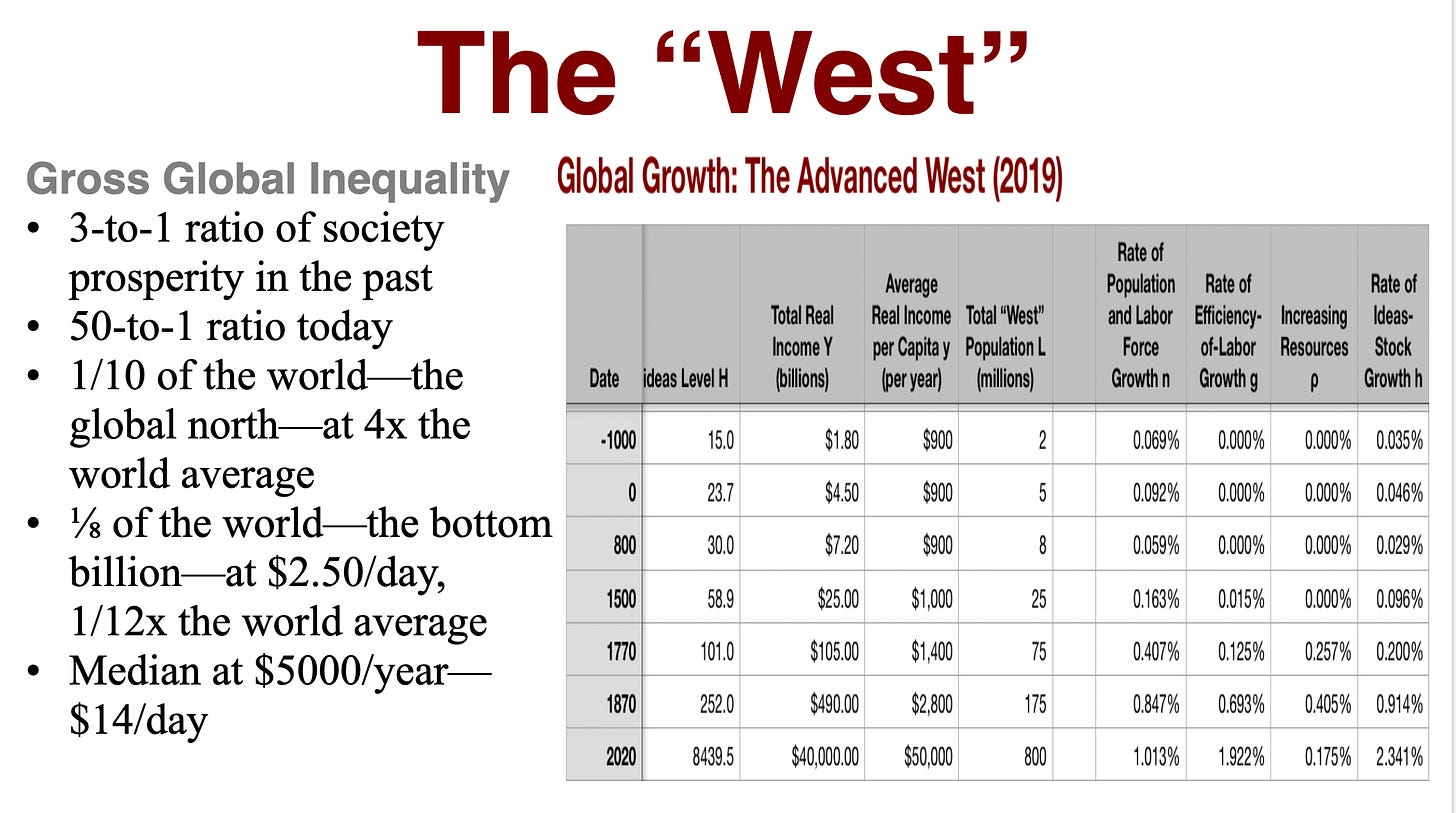

But there is more: we have also had an extraordinary growth in inequality, not so much within economies—within-economy inequality looks not that much different than in the past—but between economies. 3-to-1 was about the ratio of richest to poorest world society 500 or even 250 years ago. 50-to-1 appears to be that ratio today. And today we have the global north, the “west”: 800 million people with more than 4 times the world’s average standard of living. And we have a bottom billion living on $2.50/day. Such great gross global inequality is unique to our age.

A great deal was at stake in the three economic-history watershed-crossings of the past half-millennium. Thanks to them—although we surely are not there yet—we have the prospect of a truly human world in our future. It is not yet at hand, but it is, from the perspective of history, close.

This is the DeLongTODAY briefing. Thank you very much for watching.

3488 words

I have a recollection that the house collar was invented around 1000 CE. This technology expanded the amount of land a ploughman could turn in a day, enabling increased cultivation. There coincided, I believe with substantial population growth and other indices of prosperity such as the Gothic cathedral boom. That came crashing down with the Black Death. How would this fit with the rather grim picture of subsistence you paint here.

A very nice Sunday. Thank you for your detailed description of the ideas index. You've cited it before but never explained in detail how it was derived.