DeLongTODAY: Inflation as þe Principal Risk? I Do Not See It…

A preview of my weekly briefing for the Leigh Bureau...

<https://www.icloud.com/keynote/0XMVrM2I4wSkvRh1sJyypONhQ>

<https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/delongtoday-2021-04-09.pptx>

This is the DeLongTODAY Briefing. I am Brad DeLong, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and a sometime Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury. This is the weekly DeLongTODAY briefing. Here I hold forth here on the Leigh Bureau’s vimeo platform on my guesses as to what I think you most need to know about what our economy is doing to us right now.

I promised Wes Neff when he agreed to provide the infrastructure for this that I and my briefings would be: lively, interesting, curious, thoughtful, and relatively brief.

Relatively.

I promised I would provide briefings on a mix of: forecasting, politics, macroeconomic analysis, history, and political economy.

Today is a political economy briefing.

But first…

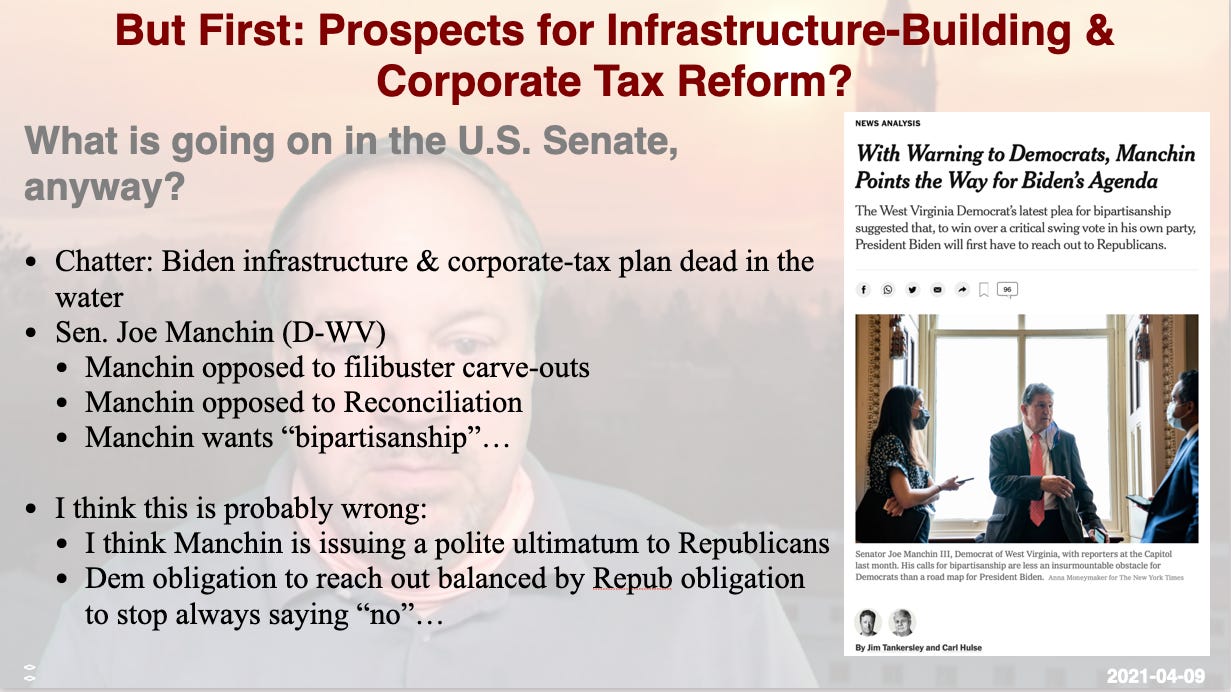

What is going on in the Senate with respect to passing phase II of Biden’s Rescue, Rebuild, Rebalance winter-spring 2021 New Deal II?

Most of the chatter I see is that parts II & III are dead in the water: that Joe Manchin won’t support eliminating the filibuster or even chopping additional loopholes in it, and will not support using Reconciliation because he believes it is essential that the Senate work in a bipartisan fashion. Therefore there is no path to anything like Biden’s infrastructure and corporate-tax proposals.

But this, I think, leaves out one important thing: Joe Manchin has a memory. Joe Manchin remembers Barack Obama going 90% of the way from his original position to the Republican position on health-care—going all the way to RomneyCare, in fact—and getting 0 Republican votes for the Affordable Care Act. Manchin remembers Obama going 90% of the way from his original position to the Republican position on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid cuts—and getting 0 Republican votes. And the Republicans making it clear that if he went 100% of the way, he would still get 0 Republican votes because the important thing was to deny victories to the Black Democratic President.

What, in the context of that history—which Manchin remembers, even if the yammerheads on TV and elsewhere do not—does Manchin’s writing “Senate Democrats must avoid the temptation to abandon our Republican colleagues on important national issues…” mean? Does it mean that Minority Leader McConnell has a veto over everything?

I do not think so. I think what it means is this: In Manchin’s view, Biden and Schumer and Pelosi are under an obligation to put forward plans that are acceptable on policy grounds to ten Republican senators—that is, things that they would vote for if they did not mind displeasing McConnell by voting for them. Then those 10 Republican senators have an obligation to vote for them if they want Manchin to continue to speak up for them in the Democratic caucus. And if the 10 Republicans do not live up to that obligation? Then, I think Manchin thinks, the Democrats will have lived up to their obligation to include “our Republican colleagues” while the Republicans will not have lived up to the obligation to “stop saying no”. Then the Democrats will settle within their own caucus what should be done.

Now they may not be able to settle. What they do will have to be acceptable to Joe Manchin, and to Joe Manchin’s long-term worries about not busting-up senatorial procedure. And what they do will have to be acceptable to Bernie Sanders. Can that gulf be bridged? Maybe, maybe not. But Joe Manchin and company are keenly aware that Biden has to be a success and has to be perceived as a success. And Bernie Sanders is keenly aware that refusing to settle for half-a-loaf in order to keep the issue live has been a catastrophic strategy in the past: much better to take half-a-loaf, and then use that as a starting point from which you can ask for the rest of the loaf.

It it's impossible to know what is going on inside the Senate unless you are a senator—and often even the senators do not know what cards their colleagues are holding and whether they are bluffing. But my guess is that there is, right now, a 20% change that ten Republican senators will cross the aisle, a 60% chance the the Democrats will do Biden’s entire deal—including the corporate tax increases—through Reconciliation, a 20% chance that the Democrats will not hang together and that small parts of Biden’s entire deal will be enacted piecemeal, and a 10% chance that nothing will get off the launchpad.

But these are only my guesses.

I was, however, very heartened to see that Jim Tankersley is thinking along similar lines. He is smart, and hard-working. And that gives me considerable confidence in my point of view here.

Jim Tankersley: With Warning to Democrats, Manchin Points the Way for Biden’s Agenda: ‘The West Virginia Democrat’s latest plea for bipartisanship suggested that, to win over a critical swing vote in his own party, President Biden will first have to reach out to Republicans…. The chances that such a compromise will materialize are slim…. Manchin’s calls for bipartisanship were less an insurmountable obstacle for Democrats than a road map for Mr. Biden… reaching out to Republicans to explore possible areas of compromise while laying the groundwork to steer around them if no such deal materializes…. Biden… aim[s] at increasing the pressure on Republicans to compromise—and, if they will not, giving Mr. Manchin and other moderate Democrats whose backing Mr. Biden needs the political cover to accept an all-Democratic plan….

People are, right now, asking me about inflation. One who did ask was Neil Irwin. Let me let my answer to him stand in for my general answer:

Brad DeLong: ‘The Federal Reserve’s inflation target has been that inflation should average—not ceiling, but average—2 percent per year using the P.C.E., 2.5 percent per year using the core C.P.I. Had inflation in fact matched that average since the beginning of the Great Recession, the core C.P.I. would now be 296 on a 1982-84=100 basis. It is actually 270. If the Fed had hit its inflation target, the price level now would be 9.6 percent higher than it is. When the cumulative excess of C.P.I. core inflation over 2.5 percent per year reaches +9.6 percent, come and ask me again whether Federal Reserve policy is excessively inflationary. Until then, we certainly have other much more important economic problems to worry about than the risks of excessive and damaging inflation…

Why is this the answer I gave?

Let me back up…

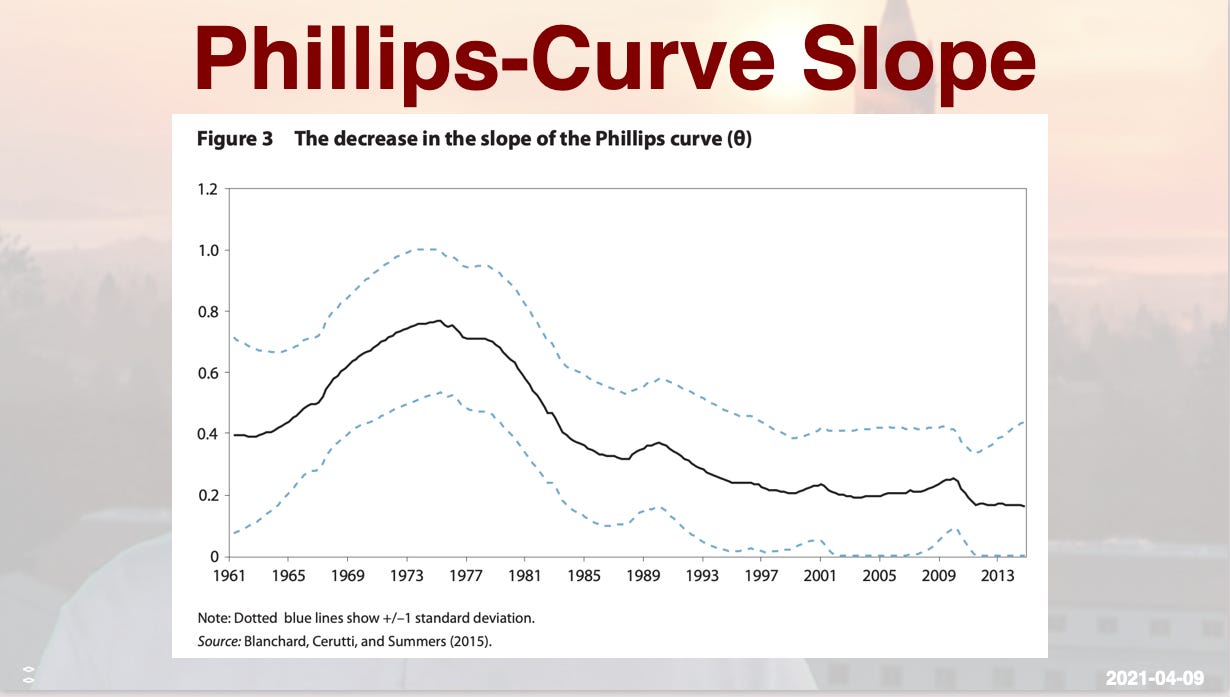

The Phillips Curve: It used to be that a 1%-point lower unemployment rate (relative to the natural rate) means that inflation would be 0.6%-points higher in a year—and, if the unemployment rate stayed low, 1.2%-points higher after two years. Now those numbers are 0.15%-points and 0.30%-points. That, however, is on the upside: high unemployment no longer reduces inflation, but until 2018 or so there was no real evidence that lower unemployment did not increase inflation. However, we got that evidence in 2018 and 2019: the predictions of the inflationistas that, finally, there would be debasement of the currency proved 100% false.

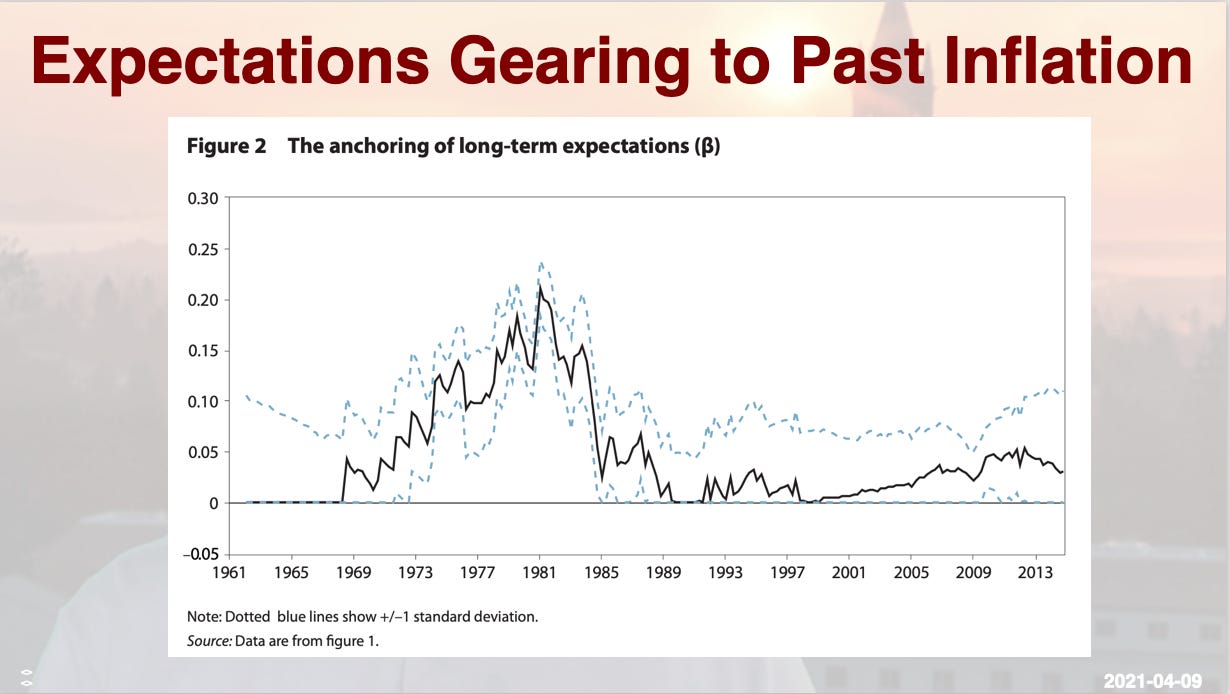

Moreover, back in the old days an increase in recent past inflation would change expectations of future long-term inflation substantially. That, too, ended in the 1980s.

It is in this context that I must observe that the models economists use for their thinking about aggregate inflation are still the models that economists settled on in the mid-1980s. It is the Phillips-Curve equations: Inflation today is equal to expected inflation plus labor market tightness pressure term plus a supply shock disturbances term:

And expected inflation today is a weighted average of expected inflation last year and what inflation actually was last year:

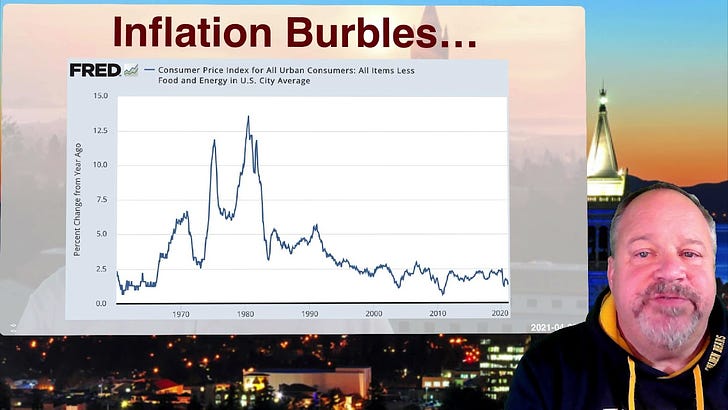

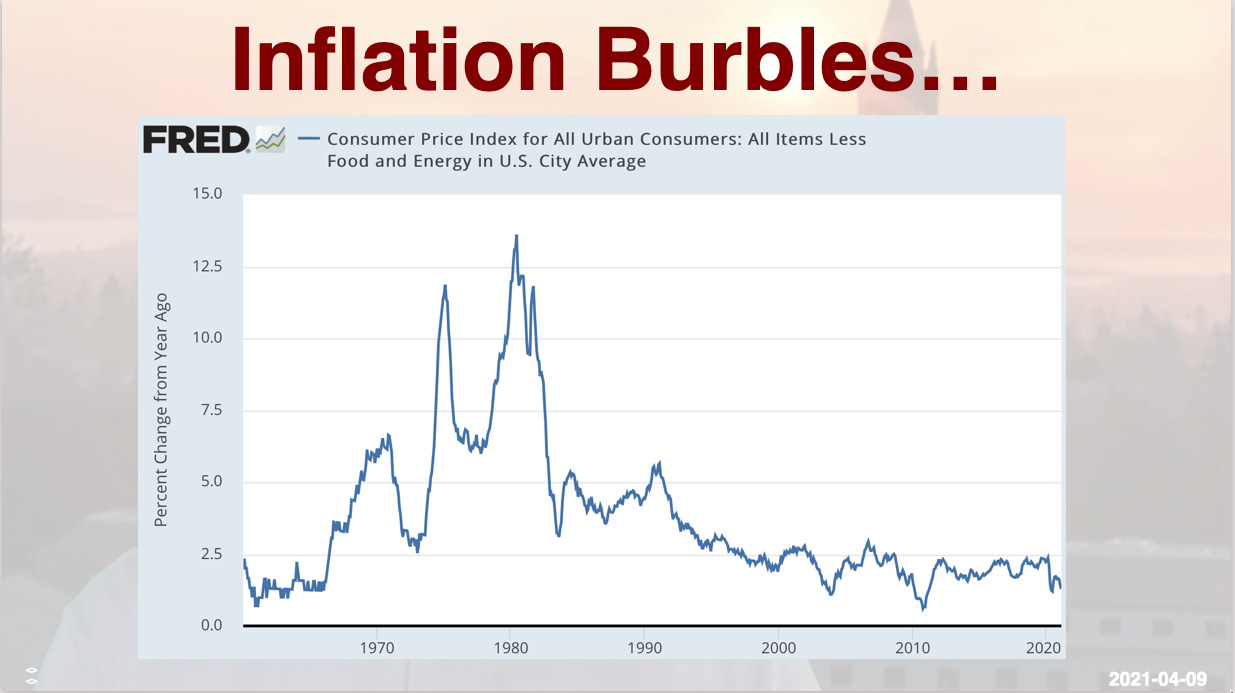

That has not described the inflation process since 1990. There has, truth been told, little to study in terms of inflation since the 1980s. It burbles along at a low level—“effective price stability” as Alan Greenspan called it. There was “opportunistic disinflation” in the 1990s—Alan Greenspan not putting his foot on the monetary gas and so allowing core-CPI inflation to gradually decline from 4% to 2.5%/year over that decade. But that, plus recession-time shortfalls of inflation below 2%/year, have been the only thing that inflation in the U.S. has done for a generation. Yet equations (1) and (2) are still how economics is taught, and how a great many economists think.

Thus since 1988 the slope of the simplest possible Phillips curve has been effectively zero, with an estimated regression coefficient of just -0.03. Even with unemployment below what economists have presumed was the natural rate, inflation has not accelerated. Likewise, even when unemployment far exceeded every estimate was the natural rate, between 2009 and 2014, inflation did not fall, deflation did not set in. It is true that we did not have any evidence, between 2001 and 2017, about what happens when unemployment is below the natural rate. But we got that evidence in 2018 and 2019. And it confirmed the belief that unemployment below what is certainly the natural rate of unemployment, if there is a natural rate of unemployment, does not generate any significant amount of inflationary pressure.

And yet we find that, once again, that the public sphere—at least the Great & Good public sphere—is roiled by discussions of inflation, and by fears of renewed inflation. The Federal Reserve FOMC, for example, seems to be genuinely split:

Greg Robb: Fed Officials Split on Outlook for Inflation: ‘Federal Reserve officials seemed divided evenly into two camps about the outlook for inflation, according to minutes of their March meeting released on Wednesday. “Several” Fed officials said that supply bottlenecks and strong demand would push up price inflation “more than anticipated,” the minutes said. At the same time, “several” other Fed officials expressed belief that the factors that had contributed to low inflation over the past decade “could again exert more downward pressure on inflation than expected.” The Fed upgraded its forecast for growth and employment and forecast that headline inflation would rise to 2.4% rate this year—above the 2% target—but then settle down to 2.1% by 2023. Despite these changes, the Fed’s median forecast was for no liftoff in interest rates through 2023. The central bank cut its policy interest rates to zero last March. The Fed said it would maintain this easy stance until the economy returns to full employment, and inflation has risen to 2% and was on track to rise moderately above 2% for some time…

LINK: <https://www.marketwatch.com/story/fed-officials-split-on-outlook-for-inflation-11617820245>

Neil Irwin <https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/24/upshot/economy-inflation.html> asked ten economists what they thought of the prospects for inflation and “overheating”. Olivier Blanchard pleaded “Knightian uncertainty… uncertainty about multipliers, uncertainty about the Phillips curve, uncertainty about the dovishness of the Fed, uncertainty about how much of the $1.9 trillion package will turn out to be permanent, uncertainty about the size and the financing of the infrastructure plan. All I know is that any of these pieces could go wrong…” Lawrence H. Summers sees “a one-third chance that inflation expectations meaningfully above the Fed’s 2 percent target… [and] become entrenched, a one-third chance that the Fed will bring about substantial financial instability or recession in order to contain inflation, and a one-third chance that this will work out as policymakers hope…. The first scenario… [is] a Vietnam-like experience where inflation expectations ratchet upwards… and… become unanchored… In the second scenario… expansion… [is] murdered by the Fed…. I can’t think of a time when we have experienced a big downshift without having a recession. In the successful scenario… we would enjoy a period of very rapid growth, followed by a downshift to moderate growth, with inflation expectations remaining anchored in the 2 percent range…”

Now this puzzles me. To say that things could go wrong under the current policy with respect to inflation needs to be balanced by the observation that things are wrong now: The prime-age employment-population ratio is at 77%, far below the 80.5% it was at the end of 2019 and even further below the 81.7% it was in 2000. The experience of the U.S. economy in the 2010s is that, without extraordinary stimulus, that ratio grows at 0.5%/year. We expect much faster growth this year as the plague ebbs. But another thing that could go wrong is a premature stalling of employment growth. And if one claims Knightian uncertainty, one then has no argument against any policy whatsoever—one only has an argument for a willingness to be flexible, and I have not found a single person who is not willing to be maximally flexible and have policy be completely data dependent.

And Summers… the Vietnam-era inflation required not just excessively loose fiscal policy, but then the mistake of excessively loose monetary policy coupled with wage-and-price controls at the end of Nixon’s first term—policy mistakes that then-Fed Chair Arthur Burns could never provide a reasoned justification for—the oil-price increase of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the U.S. government’s viewing that oil-price increase with benign neglect because it got money to the Shah of Iran he could use to buy weapons, a substantial and permanent productivity growth slowdown to collapse the wedge between wage boosts and price increases, strong unions to coordinate higher wage-growth demands, and then another oil shock, this time the Ayatollah shock. “Vietnam” was only one of seven adverse factors, and not the largest. Moreover, there seems to be a category error here: fast growth followed by a moderate recession may well leave you in a better place then slow growth because you prematurely hit the economy on the head with a brick.

I find myself in an uneasy position here. My strong instinct is to be thinking that I should agree with Larry and Olivier. But I find that I cannot.

I find myself, instead, agreeing with people like Julia Coronado, who finds herself puzzled by the worry: “For years economists [have] pined for a better mix of monetary and fiscal policy and now we have it and there is a narrative among some that it has to end in disaster. I am more optimistic… far more focused on how quickly the labor market returns to health than any threat from inflation…” I find myself agreeing with Wendy Edelberg, who “believe[s] the level of economic activity will temporarily rise above its sustainable level for a time and inflation will rise above the Fed’s target… [but] that isn’t in and of itself problematic…. Everything I see… points to a several-quarter-long surge in the economy. We — policymakers, households, businesses—need to appreciate its temporary nature and adjust accordingly…” I find myself agreeing with Claudia Sahm, who says: “It’s the spiral that matters. It could happen, but it would take a while and not only do we know how to disrupt a wage-price spiral…”

The focus on inflation risk is the product of a different era. It comes from a time when successive US administrations (those of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon) were desperate for a persistently high-pressure economy, and when the Fed chair (Arthur Burns) was eager to accommodate presidential demands. Back then, a cartel that controlled the global economy’s key input (oil) was capable of delivering massive negative supply shocks. As I said, you needed seven things, all going wrong, to produce the 1970s. Right now it is not at all clear that we have more than one.

As I told Neil Irwin:

Brad DeLong: “The Federal Reserve’s inflation target has been that inflation should average—not ceiling, but average—2 percent per year using the P.C.E., 2.5 percent per year using the core C.P.I. Had inflation in fact matched that average since the beginning of the Great Recession, the core C.P.I. would now be 296 on a 1982-84=100 basis. It is actually 270. If the Fed had hit its inflation target, the price level now would be 9.6 percent higher than it is. When the cumulative excess of C.P.I. core inflation over 2.5 percent per year reaches +9.6 percent, come and ask me again whether Federal Reserve policy is excessively inflationary. Until then, we certainly have other much more important economic problems to worry about than the risks of excessive and damaging inflation…”

I stand by that. The most recent data I have seen suggests that people getting stimulus checks are predominantly paying down debt or adding to savings rather than spending. That would mean that multipliers are even smaller in this case.

So I find myself still worried much more about stalled employment growth than inflation as the risk that we should focus on.

I’m Brad DeLong. This is the DeLongTODAY briefing. Thank you very much for watching.