DeLongTODAY: Nudging Ourselves Toward Full Employment... 2021-02-08

The rough transcript & slides for my latest DeLongTODAY briefing

From <http://delongtoday.com>

I am Brad DeLong, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley and a sometime Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury. This is the weekly DeLongToday briefing. Here I hold forth here on the Leigh Bureau’s vimeo platform on my guesses as to what I think you most need to know about what our economy is doing to us right now.

I promised Wes Neff when he agreed to provide the infrastructure for this that I and my briefings would be: lively, interesting, curious, thoughtful, and relatively brief.

Relatively.

I promised I would provide briefings on a mix of: forecasting, politics, macroeconomic analysis, history, and political economy.

Today is an economic analysis & policy briefing: is Biden doing the right thing?

But first…

Wednesday the Republican House of Representatives caucus voted 145-61 to endorse Liz Cheney as one of their leaders, and thus to approve of her for her conscience vote to impeach Donald Trump. On Wednesday half the Republican caucus also gave bigoted conspiracy theorist, Marjorie Taylor Greene—she who has called for the assassination of Democratic House leaders, denied that mass school shootings really happened, and blames Jewish Space lasers for forest fires—a standing ovation. The difference? The Cheney vote was a secret ballot. The Greene applause was public.

I harken back to 1993 and then-Treasury Secretary Lloyd Bentsen from Texas describing to some of his senior staff—and to us junior spear-carriers standing in the back of the room against the wall—what his long-time friend Bob Dole, the Republican senate minority leader, from Kansas had said to him. Dole had said that the Republican senate caucus was going to go all-in against Clinton’s deficit-reducing reconciliation bill. It needed to be done for the country’s sake, Dole said, but we Democrats would do it. And he needed to position the Republicans to pick up seats, and the best way to do that was for none of the Republicans to be onboard voting for any of Clinton’s initiatives so that Democrats could be blamed for whatever went wrong, with no water-muddying possible.

It’s been this way for thirty years. And I am tired of it. I would call the Republicans cowardly quislings, except that a not-inconsiderable portion of them appear to be true fascists rather than just going along with the Trump- and Fox-addled base, and World War II-era Vidkun Quisling stood up and was counted when he decided that enthusiastically backing Hitler was best for his career and the only political strategy that promised some hope for Norway.

So whatever is to be done needs to be done by the 50 Democratic senators and Kamala Harris, by Pelosi’s narrow House majority, and by President Biden.

So what needs to be done to bring about full economic recovery?

First, scotch the virus.

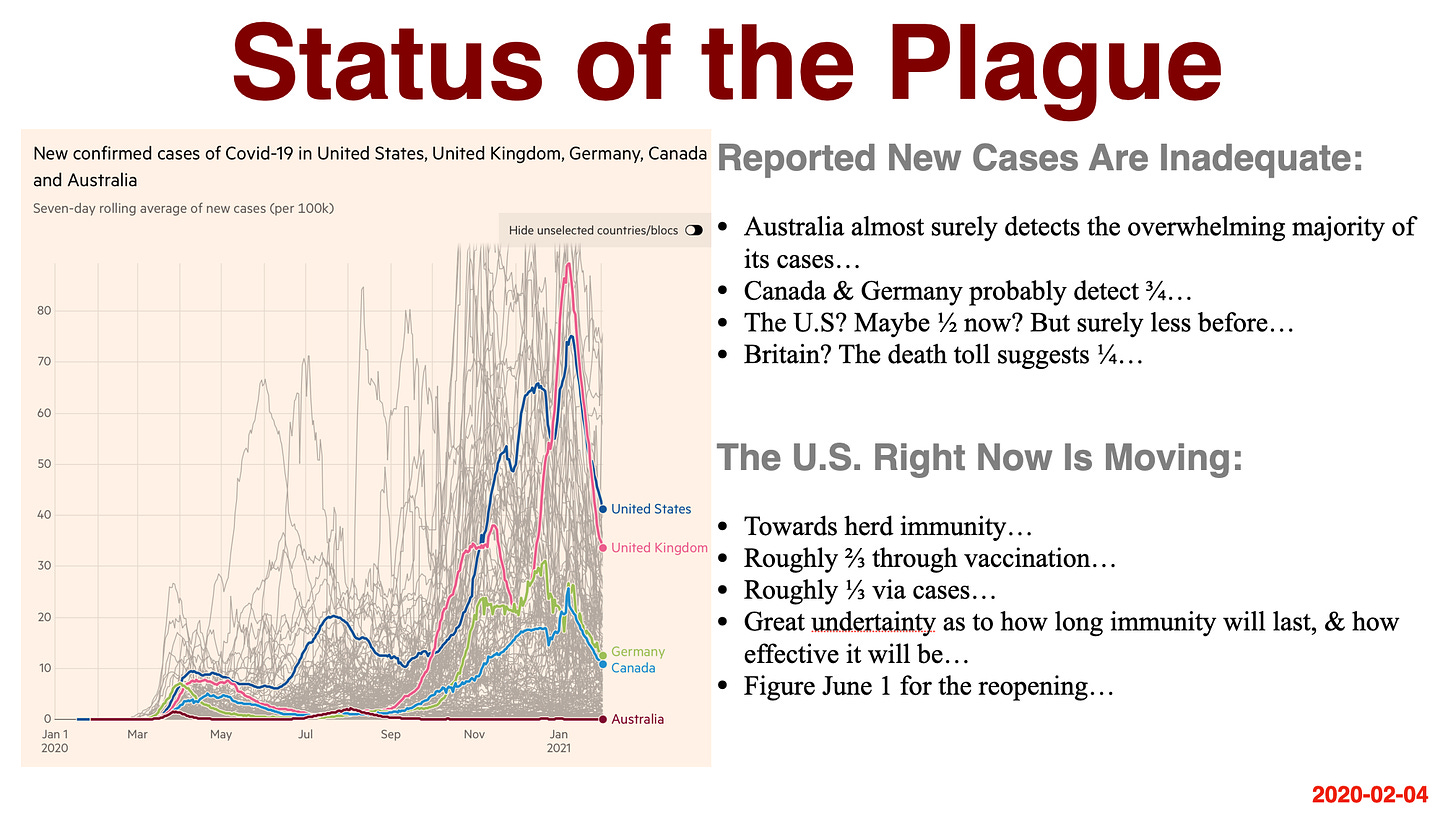

The new-case counts are, as always, hopelessly flawed. We guess that Australia detects pretty much every coronavirus case, that Canada and Germany detect 3/4, that the United States detects about half of cases now and a much smaller fraction last spring and summer and even into the fall, that that the United Kingdom—well, a case count per 100,000 roughly equal to the United States since mid-December, but 50% more deaths suggests that Boris Johnson’s MBGA government is only detecting a third. An Australian result was not out of reach for the United States, except for Trump. A German or Canadian response and result was definitely something we should have been able to achieve. We didn’t. 1 in every 100,000 Americans is now dying of COVID-19 every day. That means that roughly 1 in every 500 Americans is catching COVID every day—that is 700,000 per day, and we are only vaccinating 1,000,000. So far we have vaccinated 10% of the population with at least one dose. American Samoa has vaccinated 20%. Israel has vaccinated 60%.

Until the virus is scotched, opening up the country to restore full employment is a fool’s errand: the government needs to be focused on relief—getting families the incomes they need to live, and avoiding permanent shutdowns of businesses that we will want to have when summer comes around and the virus is scotched. But after relief, when the virus is scotched, it will then be time for recovery.

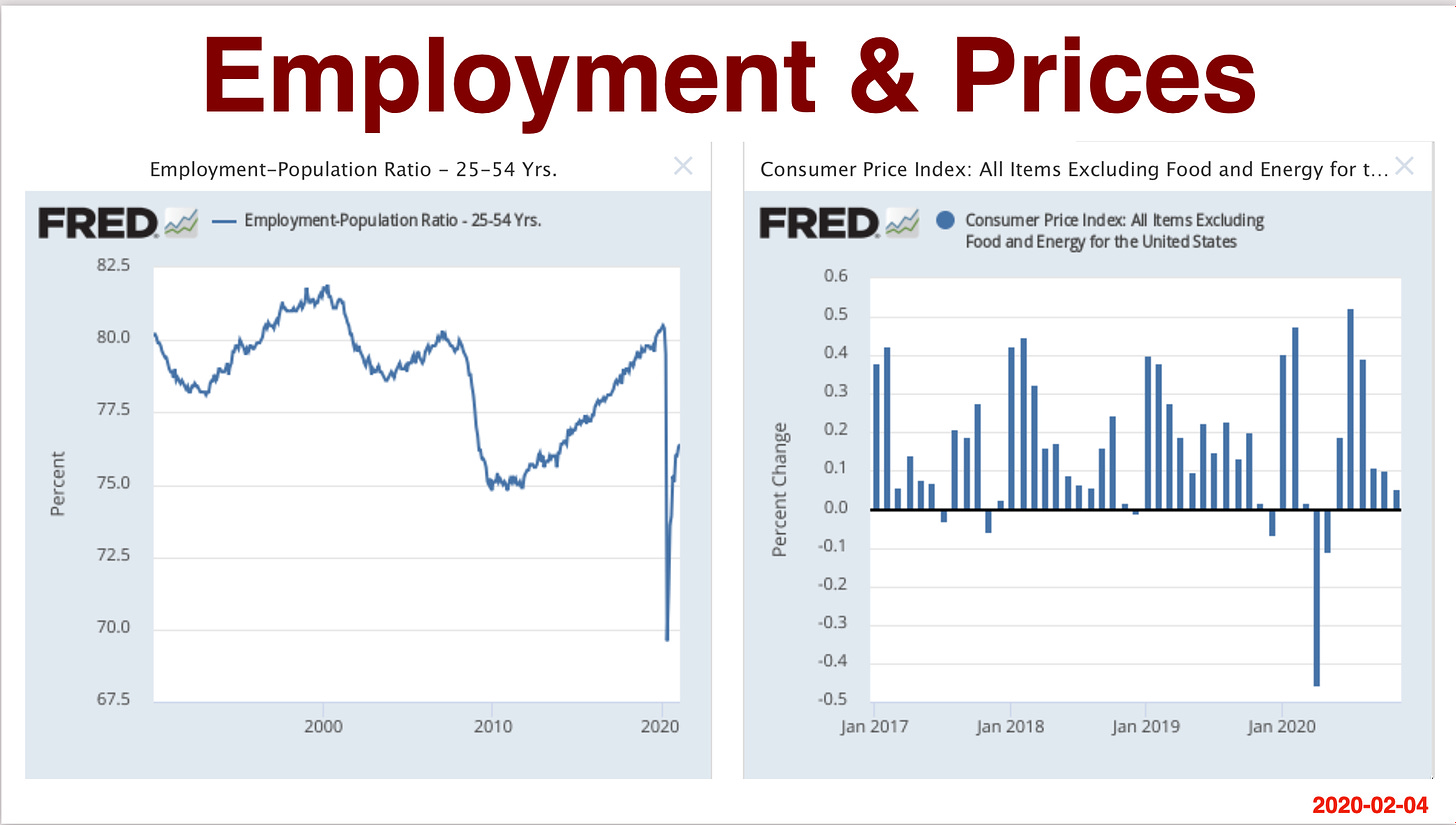

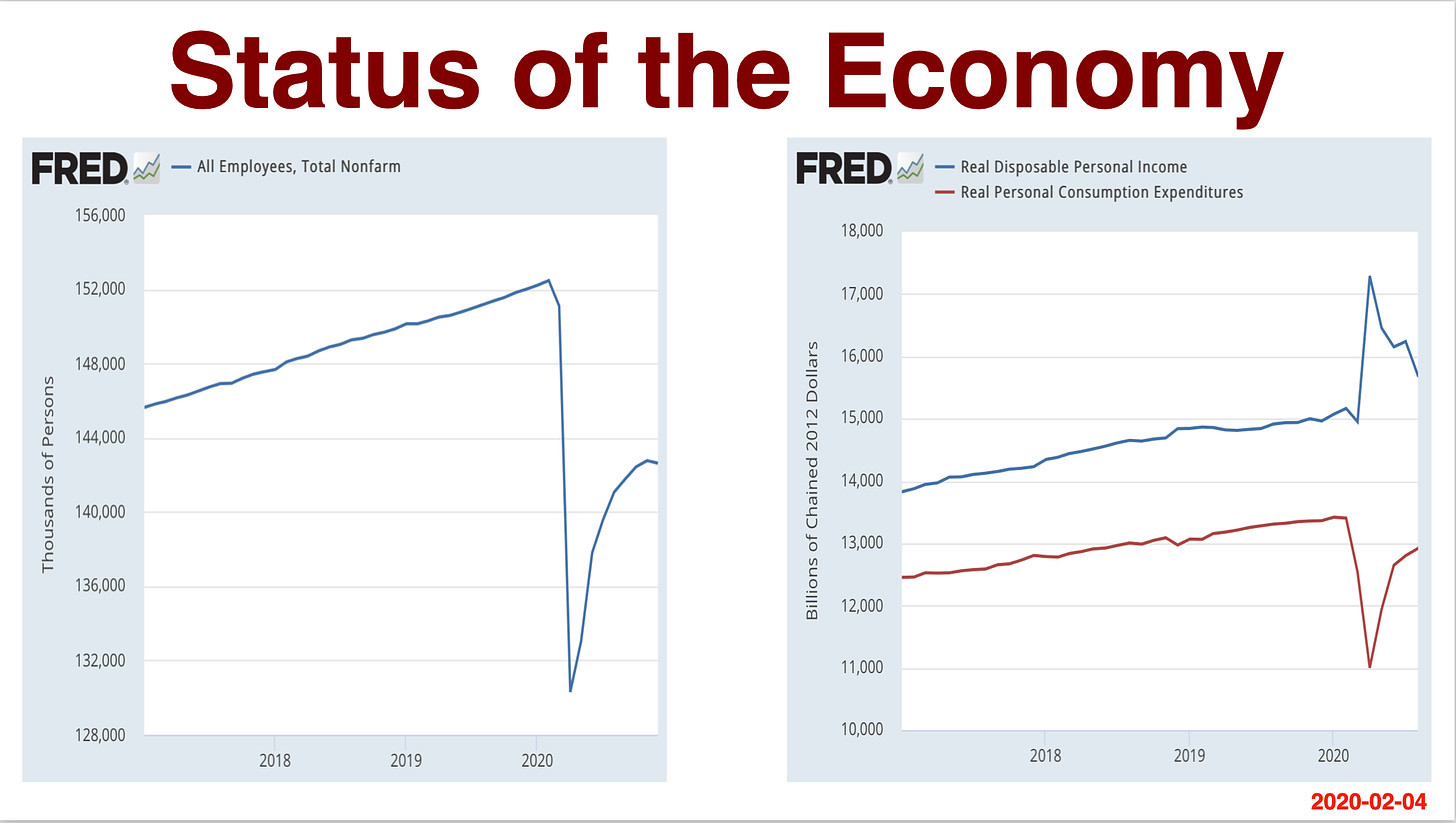

Recovery is going to start from a bad place: 143 million people at work when we want to have 155 million. This 12 million job gap cannot be filled right now: it consists overwhelmingly of workers who do not want to be at work during the plague either for personal-safety or for caring-for-family reasons plus absent customers who do not want to buy during the plague for personal- and family-safety reasons. But it is not worthwhile trying to rejigger the economy to find those 12 million people other jobs in other sectors, because we are highly likely to want them back in their old sectors by late summer at the latest. So right now we stand pat. And as we approach herd immunity we reopen. At the moment we are at, perhaps, 85 million with at least temporary immunity from past infection, 35 million with at least temporary immunity from one-dose vaccination, with that today total of 120 million growing at 2 million per day. That would mean May 1 for being close enough to herd immunity.

Will the economy then pick up its mat and walk? Will people then return to the businesses that they worked for in February 2020, and will those businesses reopen? The experience of 2008 to 2010 strongly suggests that they will not. Back then there was not a biological plague, but there was a psychological and financial plague: a collapse of finance and credit that caused the absence of financing for business and of customers for products that produced an employment gap of about our current magnitude. This financial and credit plague however, was over by the start of 2010. Interest rate risk premium had normalized. And financial institutions were recapitalized.

There was by 2010 no reason why the businesses that were in operation in December 2007 and profitable could not have resumed operation. You may object: but we needed to move workers out of construction, for, as Chicago economist now hiding out at the Hoover institution John Cochrane claimed in late 2008, "workers pounding nails in Nevada need to find something else to do”. But Cochrane and company never did their arithmetic. Employment in construction was back below its long run average share of the economy by December 2007. The fundamental sectoral labor adjustment in response to the collapse of the housing boom had already been accomplished, and had been accomplished without mass unemployment.

And yet there was no rapid recovery. There were no green shoots. There was no "recovery summer". People did not return to the jobs in the businesses, or to the types of jobs and businesses, that they had been working in December 2007 overnight, or even in years. People needed to be pulled back into the labor market by stronger aggregate demand. And a Federal Reserve desperate to normalize interest rates and its asset portfolio and fearful of letting inflation even kiss 2% per year, let alone climb above it even for a short period of time did not help. And a Republican Party eager to hamstring Barack Obama by demanding massive deficit reduction immediately without tax increases did not help. And an Obama administration conflicted and divided between those who saw the situation clearly, those who really believed that deficit reduction was Job One, and those who thought they were being clever by pretending to prioritize deficit reduction—they really did not help the situation either.

But might things be different this time? They might. And there is one important way in which the situation is different which might matter.

The way in which things are different is that there are now $3 trillion of extra savings on household balance sheets. There was no analog to this back in 2010. Then the shortfall in spending was tied to a shortfall in income with no massive household asset accumulations. There were no extra piles of savings that raised people’s wealth to income ratios substantially above their previous targets. Now there are. Is this extra $3 trillion burning a hole in people’s pockets right now? If people spend 5% of it in the year after they feel safe from the plague,If people spend 5% of it in the year after they feel safe from the plague, that would boost economic growth over the year from mid-2021 to mid-2022 by 3/4%-point relative to mid-2020 to mid-2021. if they spend 10%, the boost would be 1.5%-points. If they spend 20%, the boost would be 3%-points. "We will", as my colleague Andres Rodriguez-Clare said earlier this week, “learn a lot about savings behavior in the American economy over the next year". I think that we are as likely to see 20% as 5% because I have been persuaded by Chris Carroll's theory that Americans savers are prudent but impatient: those with money are anxious to spend as long as they can convince themselves that they are unlikely to run out and find themselves even temporarily squeezed.

This time may well be different. I would not be surprised to find this time—because of the great savings accumulation, itself for the result of the wise relief and income support policies of 2020—we do get the semi-spontaneous market led recovery without extraordinary government support and action going forward that we did not get after 2010.

So does that mean that we should not enact extraordinary fiscal support for the economy right now? Does that mean that the Biden administration is barking up the wrong tree, as are Pelosi and Schumer, in moving their $1.9 trillion reconciliation relief, support, and stimulus bill right now?

No it does not. I might be very wrong about what the central tendency likely going forward is. And even if I am right, the balance of risks is extraordinarily asymmetric, and that calls for Biden $1.9 trillion reconciliation relief, support, and stimulus bill as insurance against a repeat of the anemic post-2010 recovery.

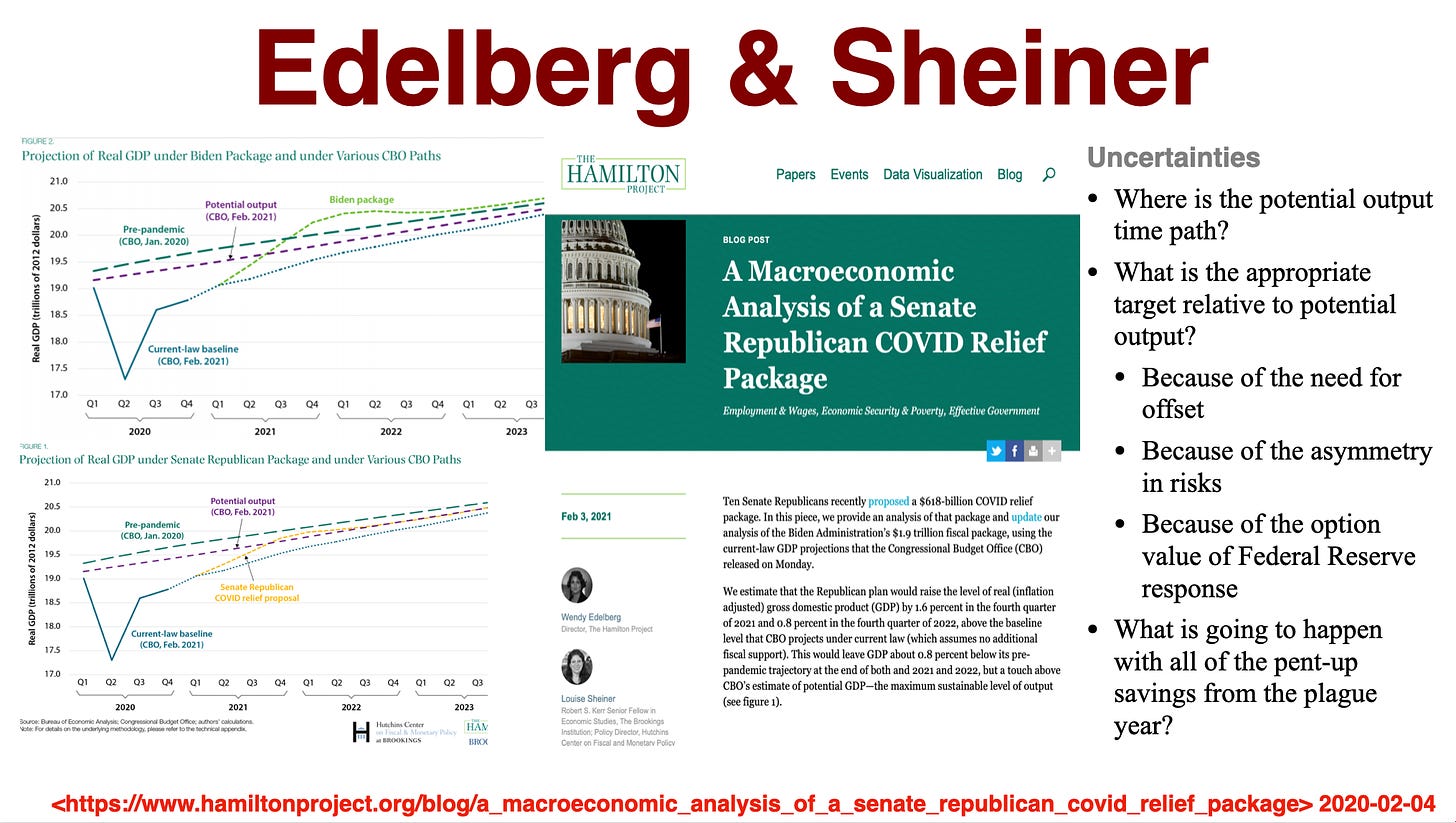

Louise Sheiner of Hutchins and Wendy Edelberg of Hamilton have just carried out a nice exercise. Let me enlarge it so that you have a chance of seeing it—I have clearly failed at the task of slide construction here. There.

Sheiner and Edelberg’s standard Keynesian counterfactual forecasting exercise is truly useful. It shows us that the Biden $1.9 trillion reconciliation bill is not well targeted as a fiscal stimulus. Indeed, it is not: it is aimed at relief and support, as well as stimulus. Doing it through reconciliation, and doing it in such a way as to hold all 50 Democratic senators in support—those impose considerable constraints on the form that it can take. As optimal policy, it fails. As politics as the art of the possible, it succeeds. And as boosting an economy that may well need boosting, it seems effective. By contrast, the Republican bill is… too small unless you accept CBO’s depressed view of what potential output is, and unless you in addition hold on to the belief that there should be no recoupment of output gaps: that potential output is a ceiling rather than an average that you should aim to fluctuate around.

But it is a mistake to conceptualize the problem of policy design here as one of producing a policy that is forecast, in the central case, either to get back to potential quickly or to overshoot potential and then return in such a way as to balance out the demand-side component of the coronavirus plague’s depression of economic activity below potential.

Instead, optimal policy design at this point in time needs to deal with uncertainties, asymmetry, and option value. It all discussion needs to start from the premise that this is quite likely going to be the only bite at the apple. It might be possible to provide a further substantial fiscal boost to the economy at sometime in the future if it is needed. But it might well not be politically possible. And it would be massively imprudent to plan on and expect that it will be politically possible to do so.

What that means is that we need to make the chance that we will wish in the future that we had done more today very low.

How about the chance that we will wish in the future that we had done less today? Do not we need to worry about that? We do need to worry about that to the extent that we do not trust the Federal Reserve to take appropriate steps to control inflation should such steps become necessary. Let me postpone the question of whether we trust the Federal Reserve to the next slide.

In order to calculate what we should do in order to have a low probability of wishing in the future that we had done more, we need to push our judgments to the edge of significant probability in three respects:

We need to act as though we are highly optimistic as to the pace of potential output growth: we do not want, after the fact, to look back and say: “gee, we really underestimated potential output growth”.

We need not to be optimistic about the multiplier in this case. We need to suppose that that portion of the reconciliation bill money that is going to those who normally have a low marginal propensity to consume will not materially boost the pile of savings that are burning a hole through their pockets and that they will spend quickly. It is thus prudent to suppose that only those income boosts that hit the truly liquidity constraint will be spent. And that is significantly less than half of the total spending bill.

Shouldn't we then take steps to craft the bill more carefully? If we are giving money away to people who are not liquidity constraint for no good macroeconomic purpose, shouldn't be halt those expenditures and so avoid such a great increase in the national debt? If interest rates were positive, the answer to that question would be yes. But since interest rates are not positive and since we want to have this bill having its impact on the economy over the summer, it seems best to postpone issues of debt management and income distribution and so forth into the future, and right now focus on relief, support, and stimulus.We need to presume that Americans understand that the world is now a riskier place then we thought it was a year and a half ago. Thus we need to presume that increases in wealth to income ratios even among rich households reflect the changing definition of prudence rather than sums that are going to be rapidly spent-down as a result of impatience.

All of these, I think militate strongly in support of the Biden package—as long as we can trust the Federal Reserve to handle problems that emerge if the policy does what it is supposed to do, that is, boosts production and employment up above potential output and beyond full employment in the absence of monetary policy offset.

So can we trust the Federal Reserve? One thing seems certain about Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell: he will not make his "temper tantrum" mistake again. He and his open-market committee will not prematurely withdraw monetary stimulus before he sees the whites of rising inflation's eyes.

Does that mean that he will hesitate to withdraw monetary stimulus and impose monetary austerity if we do reach a situation in which inflation control is rightly the highest priority of the Federal Reserve? Will Jay Powell, if faced with a return of the 1970s, turn into the equivalent of an Arthur Burns or a G. William Miller and, either out of a sense of loyalty to his political patrons, or out of fear of losing the Federal Reserve’s independence through policies Congress judges as excessively austere, or by misjudging the situation?

Never say “never”.

But the odds of that seem to be extremely low. First, the more we look at how industrial economies behave, the more it looks as though the inertial inflation of the 1970s was a one off produced by a unique confluence of a central bank that did not take its price-stability mission seriously and an economic structure in which major moves in the price of a single crucial commodity—oil—both of very powerful fundamental importance and served as a signal on which market participants could condition their own inflation expectations. No key fundamental role of oil, no conditioning of market expectations of inflation on the oil price, no absence of trust in central banks, then no inflation of the 1970s.

I am highly confident that Jerome Powell will neither make the Greenspan mistake of viewing unregulated bubble finance with benign neglect, the Bernanke mistake of premature normalization come hell or high water, nor the Burns-Miller mistakes. He will make his own mistakes. But we do not know what those will be. And we should not fear him making Burns-Miller mistakes in the future and have that fear lead us into avoiding appropriate fiscal stimulus out of fear of what is in the shadows.

So, yes, I do think that the Biden reconciliation bill for relief, support, stimulus is highly appropriate at this moment and deserves to pass. And I think it will do a lot of good in easing America's recovery. At this point it is traditional to say something about sausage and legislation. But I do not think we really need to say that: this looks to me like as much of a technocratic triumph as one can have in this fallen sublunary sphere, in this sewer of Romulus in which we live and work.

I am impressed with the policy design and with the marshaling of the political coalition.

That is, I am impressed with the policy design and the marshaling of the political coalition among the Democrats.

I am not so impressed with the Republicans. These do not seem to me to be partisan issues here. I could understand if the right wing of the Republican Party, with its ideological blinders and its deficiencies and its inability to avoid thinking of an optimal policy is very different when a Democrat than when a Republican is president were to show up with a $600 billion proposal. I am rather embarrassed for the moderate, non-fantasy-based wing of the Republican Party when that is what it brings to the pot-luck

I’m Brad DeLong. This is the DeLongTODAY Briefing. Thank you for watching…

====

3070 words 31:36 2020-02-05