DeLongTODAY: þe U.S. Minimum Wage—What Should It Be, Technocratically & Neoliberally? 2021-02-12

þe cript, & c., for my 2021-02-12 Fr DeLongTODAY Leigh Bureau video briefing...

This is the DeLongTODAY Briefing. I am Brad DeLong, an economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and a sometime Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury.

Here I hold forth here on the Leigh Bureau’s vimeo platform on my guesses as to what I think you most need to know about what our economy is doing to us right now.

I promised Wes Neff when he agreed to provide the infrastructure for this that I and my briefings would be: lively, interesting, curious, thoughtful, and relatively brief.

Relatively.

I promised I would provide briefings on a mix of: forecasting, politics, macroeconomic analysis, history, and political economy.

Today is mostly an economic analysis situation briefing: the minimum wage. What should it be, technocratically and neoliberally?

But first…

The DeLong SubStack: <http://braddelong.substack.com>

Paul Krugman started a “SubStack”

So I am going to be starting one too: <http://braddelong.substack.com>

What is a SubStack?

SubStack is… classical weblogging—but. What is the “but”? The “but” is:

A very aggressive push of the post to the email inbox of the recipient, rather than waiting for the recipient to come surfing by, with perhaps an rss-flag tickler to remind readers to come by. A subscription email with a website attached, rather than a website with a push RSS feed attached.

A very, very aggressive focus on what used to be called the tip jar, which hath now fed upon that meat upon which Cæsar doth feed and grown great, and morphed into a paywall.

A focus on longer-form—a newsletter rather than a log of readings and reactions. (That, however, may not turn out to be the stable form of whatever medium it turns into: Adrian Hon’s <http://mssv.net> used to have three columns—links with a phrase or a sentence, paragraphs, and essays.)

SubStack is—like Medium <http://medium.com> before it—at one level an explicit reaction to the consumption and destruction of what appeared to be a growing weblog-based public sphere by Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and company—each of which consumed part of the space, and each of which succeeded in generating superior dopamine-hit random-reinforcement engagement, which turned what I at least regarded as a functional and improving intellectual ecosystem into: the Net of a Million Lies.

I guess the game is to return Facebook to its role of posting updates for family and friends; to turn Twitter into SubStack’s comment section, and to, as Hamish writes up top, provide “a calm space that encourages reflection… free of advertising or any other distraction… no addiction-maximizing feeds, autoplaying videos, or retweetable quote-retweets to suck you into a psychological space you never asked to be in…”

Will it work? Probably not. Can it be worse than Zuckerberg’s or Dorsey’s firehoses of fear-generating misinformation? Almost surely not. Thus it is, I think, worth trying. As Noah Smith said on the inaugural edition of our Hexapodia podcast <https://braddelong.substack.com/p/hexapodia-is-the-key-insight-i-relief> <https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/47874.rss>, we have already tried everything else, with less persistent success than Sisyphus.

The Minimum Wage

Let me start with how economists currently understand the minimum wage—how the literature on how the labor market works started by David Card and Alan Krueger has led people to think about the issue.

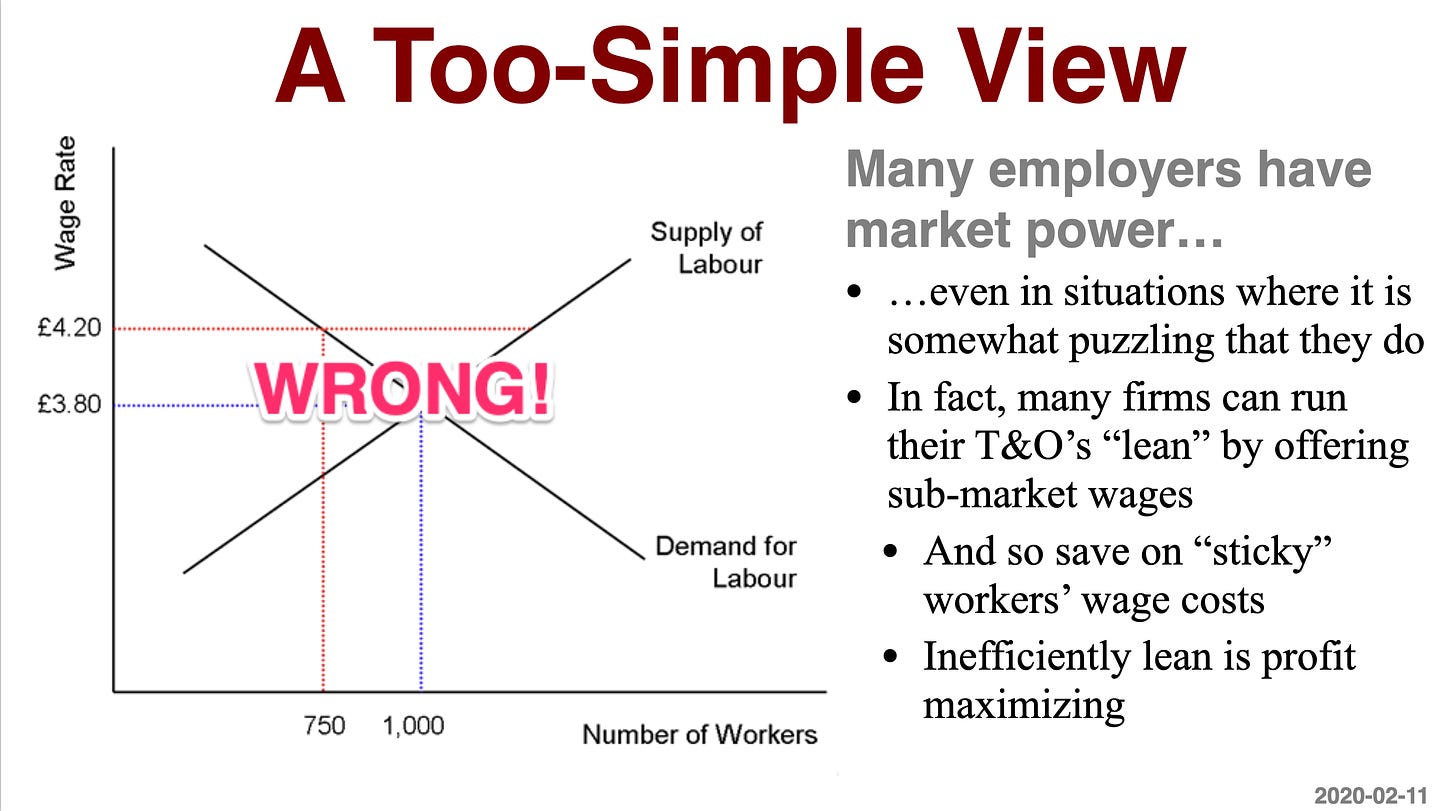

There is a too-simple view of the labor market. It is that when you hire a worker, you have to pay an amount proportional to that worker’s quality to attract them away from other possible jobs because the market is in equilibrium and effort and skill are rewarded. Offer to pay a wage 50% higher, and you attract a pool of workers who cannot get higher-paying jobs. Select the best ones out of that pool and you find you have workers who do 50% more work than you got from the workers you could hire at the old, lower wage that you had been paying. You thus have no market power to choose the wage you will pay per unit of work. And so you keep on hiring workers until the value to you an extra worker produces—his or her marginal revenue product—is just a bit above the cost per unit of work that the market-in-equilbrium makes you pay.

That way of understanding the labor market seems to be wrong.

Instead, when you cut the wage you pay, you find that you do have trouble attracting workers to fill all the slots in your table of organization: you would, if you could do it, rather have your organization more fully staffed-up because you are leaving money on the table: an extra worker on the shift would bring in more extra money than their wages. But when you cut the wage you pay, you also save because you are paying your non-marginal workers—those who feel themselves stuck to the job—less as well. What you lose because you are running your organization with inefficient staffing holes in your table of organization you make up for by a lower wage bill in general. A low-wage policy that gives you an inefficiently-lean organization is thus the profit-maximizing one.

Now I find it a mystery why so many low-wage workers appear to be stuck to their jobs—why is it sufficiently difficult to find another one nearby and as good that employers, even small employers, even small employers in densely populated areas, have “market power” in the sense that they can choose how much they will pay per unit of, as Marx would say, labor power hired? I do not understand well. But it is.

So suppose we have such a labor market, and we take employers’ power to choose what they will pay their lowest-paid workers away from them: we raise the minimum wage. They then no longer have the power to choose to pay less, thus saving wage costs for all their workers stuck to the job. So they keep hiring until marginal revenue product equals wage costs—you thus get a higher level of wages in the low-wage part of the labor market, and also a higher level of employment. A higher minimum wage thus creates jobs.

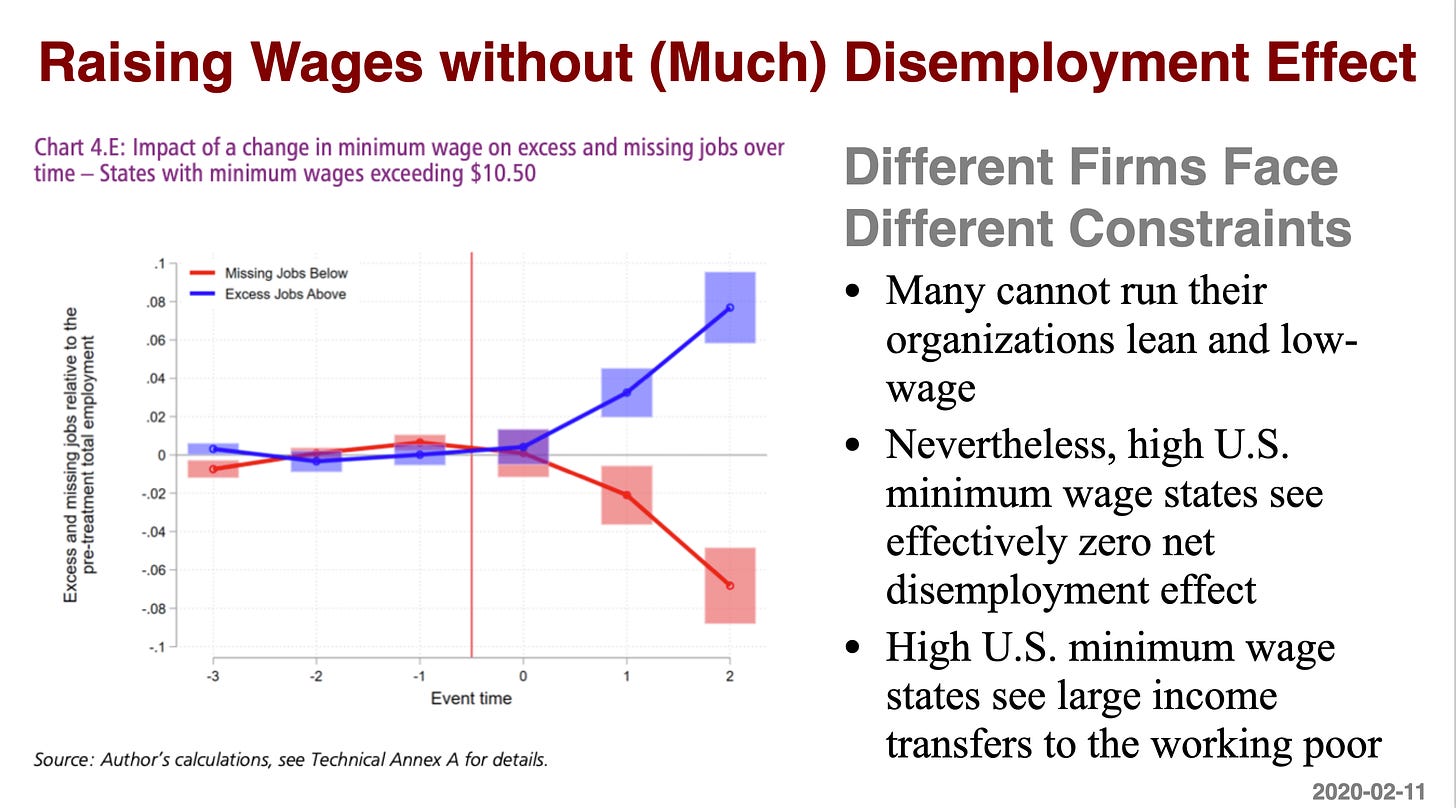

Now this part of the labor market—the one in which firms have market power because workers are sticky-at-the-job, the one in which as long as the minimum wage is not binding firms can thus choose to save on the wage costs of their sticky workers by refusing to pay the prevailing market wage needed to fill their table of organization so that the firm runs with optimal efficiency—is not the whole of the labor market. There are jobs where workers are not sticky. There are firms that hire up to the point where the wage equals the marginal revenue product. And for those firms, a higher minimum wage discourages employment.

As we consider higher and higher minimum wages, those firms where the effect of a higher minimum wage is to reduce employment become more and more salient. Those firms where the effect of a higher minimum wage is to remove the incentive to run the firm in an inefficiently lean manner become less. When the minimum wage is very low, odds are that increasing the minimum wage will boost employment. When the minimum wage is higher, odds are that it will reduce it.

So where is the sweet spot? What is the sweet spot? How can we tell where the sweet spot is?

The first thing to note is that the sweet spot is not the point at which the minimum wage level results in the most jobs. The minimum wage’s effect on the level of employment is a side effect. The purpose of the minimum wage is to ensure that the market is our servant, not our master—that the market was made for man, not man for the market. The market economy needs to deliver a fair distribution of income and wealth. Having the minimum wage to make sure that even low-wage jobs are fairly remunerated is an important part of that.

As Adam Smith wrote back in 1776:

No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable…

And he went on to immediately add:

It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, clothe, and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labor as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged…

The sweet spot for society as a whole is above the point at which the employment-inducing effect of the minimum wage is exactly offset by the growing employment-shrinking effect.

The second thing to note is that a good minimum wage policy is one that is properly supported by other policies. There is, in addition to the minimum wage, the Earned Income Tax Credit: the government tops off your wage via sending you a check if your hourly wage is sufficiently low. Expansing the Earned Income Tax Credit both gets more money to relatively poor workers are increases employment by providing workers with an incentive to take jobs at wages they would otherwise find not worthwhile. If you are worried about the disemployment effect of the minimum wage, there is a simple solution: when you raise the minimum wage, also expand the EITC so that the employment-inducing effect of the second offsets the employment-reducing effect of the first.

So why, you may ask, have a minimum wage at all? Why not just have an EITC? The problem is that the IRS is not set up to evaluate and audit EITC claims. The IRS is set up to deal with data flowing in in which there are powerful incentives to create accurate data. A firm that underinvoices what it sold diminishes its own tax liability, but that underinvoice means that the firm it sold to must thereby underestimate its own costs, and so raise its tax liability. By contrast, EITC-relevant reports have no such internal checks. It is thus “difficult to administer” fairly and cheaply—a lot of energy needs to be devoted to checking to achieve a tolerable “error rate”. Not that the EITC is a bad program. But it is not a perfect program.

By contrast, the minimum wage is easy to administer. Once the minimum wage is broadly known, it all but administers itself. Workers know what the minimum wage is, and to whom they should complain if they are stiffed. On the one hand a program that all but administers itself, but that at some point has a disemployment effect. On the other hand a program that has an employment-encouraging effect, but that is difficult and costly to administer—and requires taxes somewhere else in the system with their own drawbacks to finance. There are tradeoffs, so you seek a balance. Thus a good income-support policy for low-wage workers should have both an EITC and a minimum-wage component. It should not be all one or all the other.

A parenthetical remark: If you find anyone who claims that the minimum wage ought to be set at the employment-maximizing level—at which the employment-inducing and employment-discouraging effects balance out, without noting that making the wage distribution fairer is a goal and that a higher minimum wage than the zero-effect level is in fact the sweet spot—they are not your friend. They are not trying to educate you or discuss issues with you, but to deceive you and swindle you. Similarly, if you find anyone who talks about the minimum wage in isolation—without ever noting that when you worry about disemployment effects you should not just moderate the increase in the minimum wage but also adjust other employment-encouraging policies at the margin as well—they are, also, not your friend. They are not trying to educate you or discuss issues with you, but to deceive you and swindle you.

So with all that as prologue: What should the minimum wage be in the U.S. today? And should it vary from place to place? And how much should it vary from place to place?

To answer that, we need to decide (i) what the world is actually like, and (ii) how much we care about boosting the incomes of low-wage workers on the one hand via discouraging employment on the other. The first is not an ideological question, but an empirical-technocratic one. What is the answer?

Unfortunately, if you want the answer to that, you cannot look at Phil Swagel’s Congressional Budget Office <https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2021-02/56975-Minimum-Wage.pdf> right now. It says that the employment elasticity—the amount by which employment falls when the minimum wage rises—is -0.48. Or, rather, it does not **say** that. As Jordan Weissman wrote <https://slate.com/business/2021/02/minimum-wage-hikes-cbo-relief-bill-democrats.html>: “in a stark and slightly suspicious failure of wonk transparency, the budget office did not actually state outright the number they chose to use anywhere in their report…” It’s not a slightly suspicious failure, Jordan: it’s an unprofessional lapse. I expected professional behavior from Phil. And I am greatly disappointed.

The CBO’s estimates of an increase in the minimum wage to $15/hour nationwide are: an extra $33 billion a year in pay to low-wage workers, a 900,000 reduction in the number of people in poverty, and a 1.4 million reduction in employment. That corresponds—but recall the CBO does not say—to an estimated employment elasticity of -0.48. And that is very large. My estimate of the employment elasticity over the range from the current value to $15/hour is that it is probably somewhere between 0 and -0.15.

How did they get to -0.48? Since they do not say that that is what they use, they choose not to defend it at all. Again, unprofessional. They do say that had they followed the methodology they followed when they last looked at the issue in 2019, they would have estimated 1.1 rather than 1.4 million. And they do say that they chose 1.4 million because they think there is a chance that the elasticity might truly be much bigger than the near-consensus of study estimates is. We can do some math. Suppose that there were a 40% chance that the near-consensus was correct, and that the near-consensus was 1.1.; suppose that there were a 30% chance that the near-consensus was pessimistic, and that the optimistic number was 0.8; and suppose that there were a 30% chance that the near-consensus was optimistic.

What would the pessimistic number have to be to make sense of 1.4? It would have to be… 2.4 million. With 30%-40%-30% probabilities, and 0.2 and 0.3 optimistic and near-consensus elasticities, the pessimistic-scenario elasticity would, arithmetically, have to be 1.1: in the pessimistic scenario, raising the minimum wage would **reduce** the total income of low-wage workers because the share fired would be greater than the proportional wage increase.

I know of no economist of note and reputation who believes that that is true in the range from the current minimum wage to $15/hour. I may have gotten the CBO’s calculations wrong—they, unprofessionally, do not spell them out. But unless I have, I simply see no professional method at all here.

So what should the minimum wage be, technocratically—and neoliberally, using market and market structuring mechanisms to advance near-consensus societal well-being?

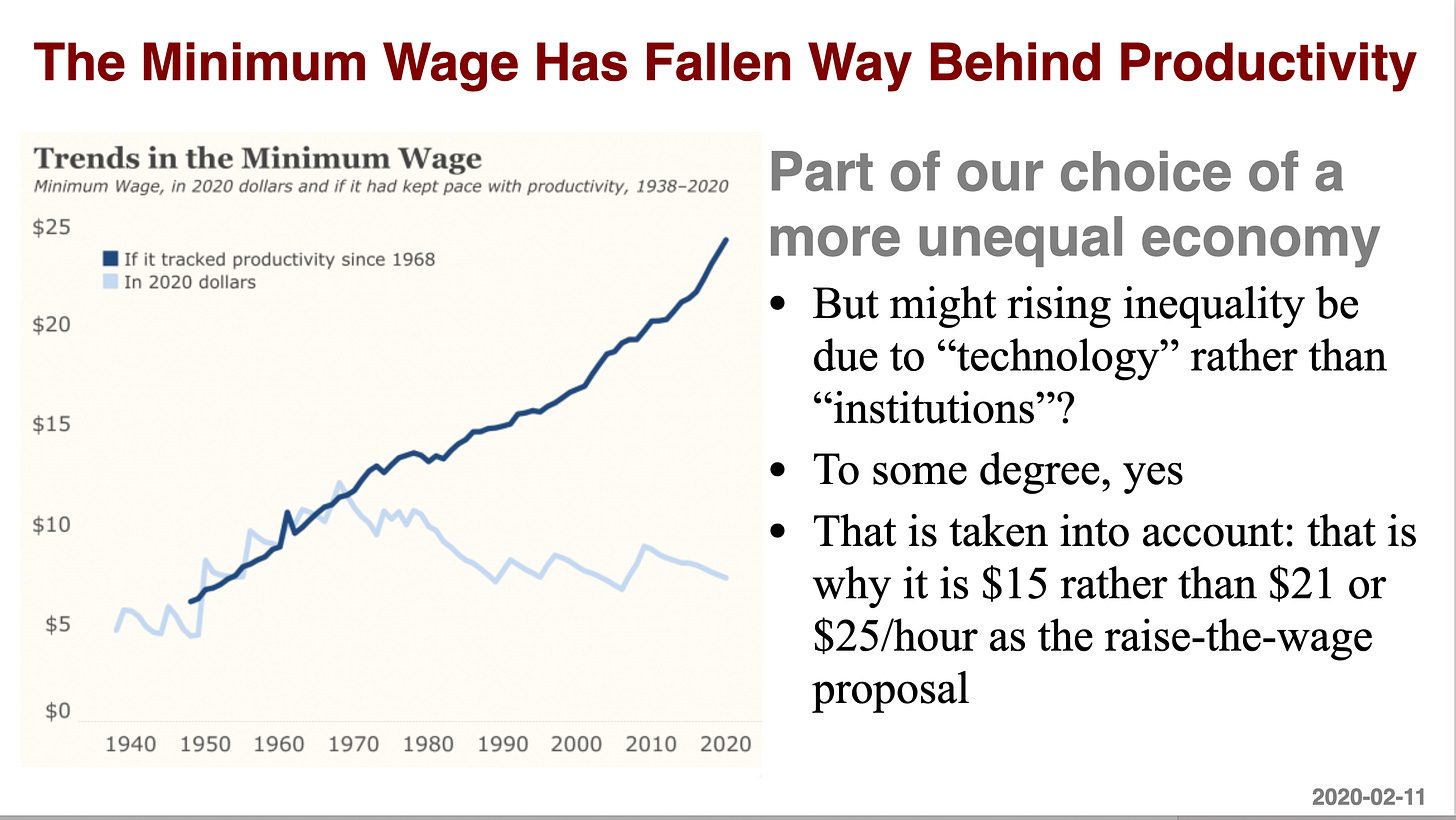

As Heidi Shierholz and my colleague Jesse Rothstein just wrote: “The rise in inequality over the last decades has been a choice…. Institutions… have been weakened or attenuated and have helped the one percent absorb ever increasing shares of national income. One of the most glaring examples of this has been the minimum wage…. A wage floor that had kept up with productivity growth since the late 1960s would be over $21 per hour today…. Increas[ing] the minimum wage in five steps to $15 per hour in 2025… [would directly] benefit… 32 million workers, their families and their communities. Nearly one-third (31 percent) of Black workers, more than one-quarter (26 percent) of Hispanic workers and 26 percent of women…”

My view: we could afford the minimum wage back in 1968—it had no significant disemployment effect. You might argue that a good part of the increase in income inequlaity and since reflects “technology” and not “institutions”—and I would say that that is why Bernie Sanders and company are only proposing $15 and not $21. The “technology vs. institutions” debate over the causes of rising inequality has already been taken into account in choosing $15.

I do believe the argument against a nationwide $15 an hour minimum wage has some bite in low-productivity and low-wage states. Unfortunately, I find that I cannot trust state governments in low-productivity states to properly value the interests of their low-wage workers. If I could be reasonably sure that state governments wanted a carveout from the $15/hour minimum wage because they really believed that that was best for their states’ low-wage workers, I would be enthusiastically in favor of such a carveout. But since I am reasonably sure that is not the case, what to do?

I propose that states that seek a carveout from the $15/hour minimum wage do so by topping-off the EITC in their states instead. And if a state is not willing to offer such a top-off? It should not be offered a carveout. That, I believe, is incentive compatible. And fair.

It is, I think, corrosive of our democracy and our republic that opponents of minimum-wage increases rest their argument on junk economics claims that raising the minimum wage would be bad for low-wage workers, without putting forward ancillary policies to mitigate the harms they claim that they are concerned about. it is corrosive because, I think, those who do say they worry about disemployment effects are, for the most part, worried about something else—they think that the market is fair, and that disturbing the market’s distribution of income via a minimum wage is unfair. But they do not want to say that. And so we have a public sphere that is fed lies. And it does not work very well.

2992 words

I find this purely economic argument unsatisfactory.

Firstly, I find it far too narrow, ignoring externalities. A certain level of crime is due to insufficient income to live. This requires creating prisons, housing them at higher costs than in society, hiring increasingly aggressive police forces and the paraphernalia of the state's law enforcement institutions, which includes servitude on jury duties. Increase teh minimum wage and crime should decrease by some extent, reducing all these external costs. What might be the needed minimum wage (and associated UBI?) to achieve this?

Secondly, while your analysis makes sense today, but what about in the future as automation eliminates many jobs, including those with minimum wages. Unlike horses as automobiles appeared, we cannot send people to the knacker's yard. Wage-earners cannot compete with machines. Unless there continue to be requirements for people to operate the machines and be paid to do so with a commensurately higher wage, employment will decrease and we will need to find ways to maintain an impoverished population. I suspect this will make minimum wage issues superfluous to the real issue - how do we maintain a population that is largely useless in the wage economy? Raising wages in some form now to aid voluntary retraining, education, and skills acquisition, as well as some form of real social cushion in the face of future pandemics and long term unemployment that is independent of political paymasters, need to be planned for now.

A technocratic analysis of minimum wage levels might be useful today, but it strikes me as very short-sighted when one lifts one's eyes to the needs of populations as intelligent automation rushes towards us.