DOCUMENT: 1959-07-14: Peng Dehuai to Mao Zedong

Without a doubt, one of the most pivotal documents of modern Chinese history...

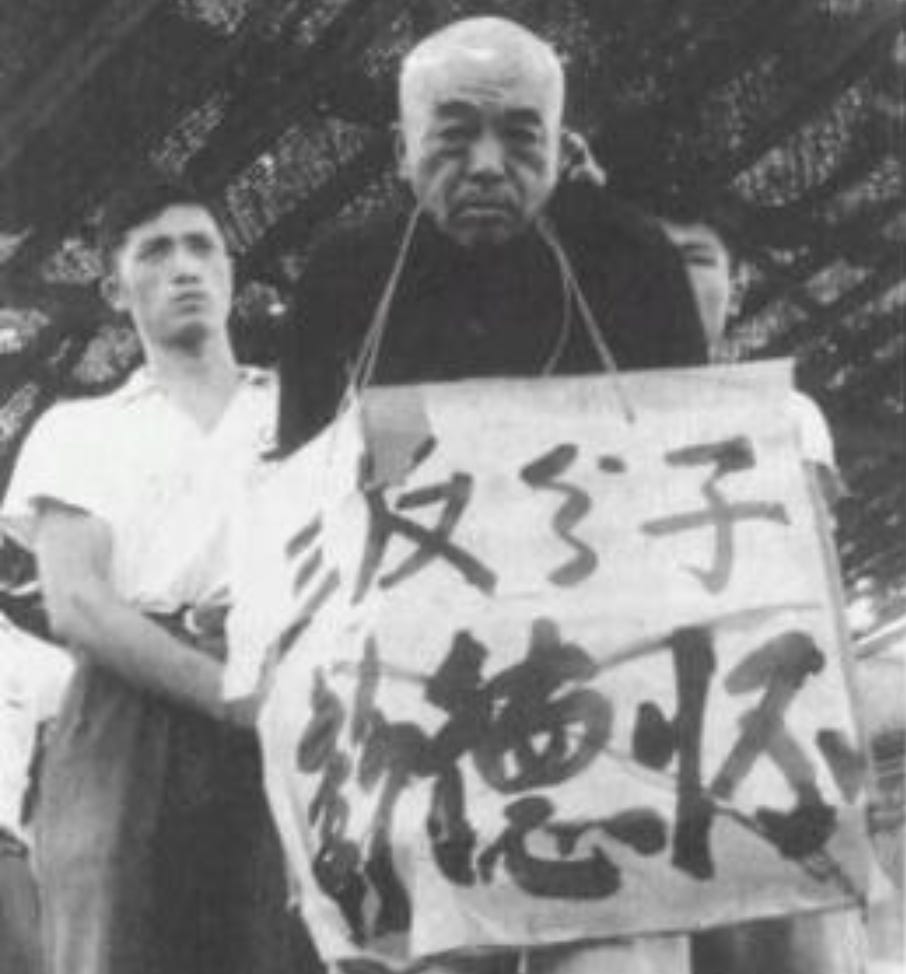

Written half a month before the 8th Plenary Meeting of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party that was held at Lu Mountain in Jiangxi, this attempt by Marshall Peng to turn policy around and save some of the 50-100 million citizens of China who were then about to starve to death. Peng was purged. Later, in the Cultural Revolution, with Mao’s active blessing, the Red Guards were to torture him, and denounce him as a “capitalist great warlord": “we have to struggle against him until he falls, until he breaks down, until he stinks.”

His health broken—serious blood clots—and with Mao ruling that his conditions should not be treated, he went into a decline, dying in 1974. The story is that his last request was to be allowed to see the sun and the trees through the window, but it was declined.

My belief is that Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping (and perhaps Zhao Enlai?) encouraged Marshall Peng to challenge Mao and attempt to reverse the Great Leap Forward policies that had set China on the path to famine, but then double-crossed him—or simply lost their nerve. However, in the aftermath of the Lu Mountain Plenary Meeting, Mao was to some degree sidelined. And by 1961, Liu Shaoqi was attributing 30% of the responsibility for the famine and 70% to mistakes—Mao’s mistakes. Mao then made a tactical retreat, ceding authority over the management of the economy to Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping as they tried to salvage the situation and reduce the scale of the disaster.

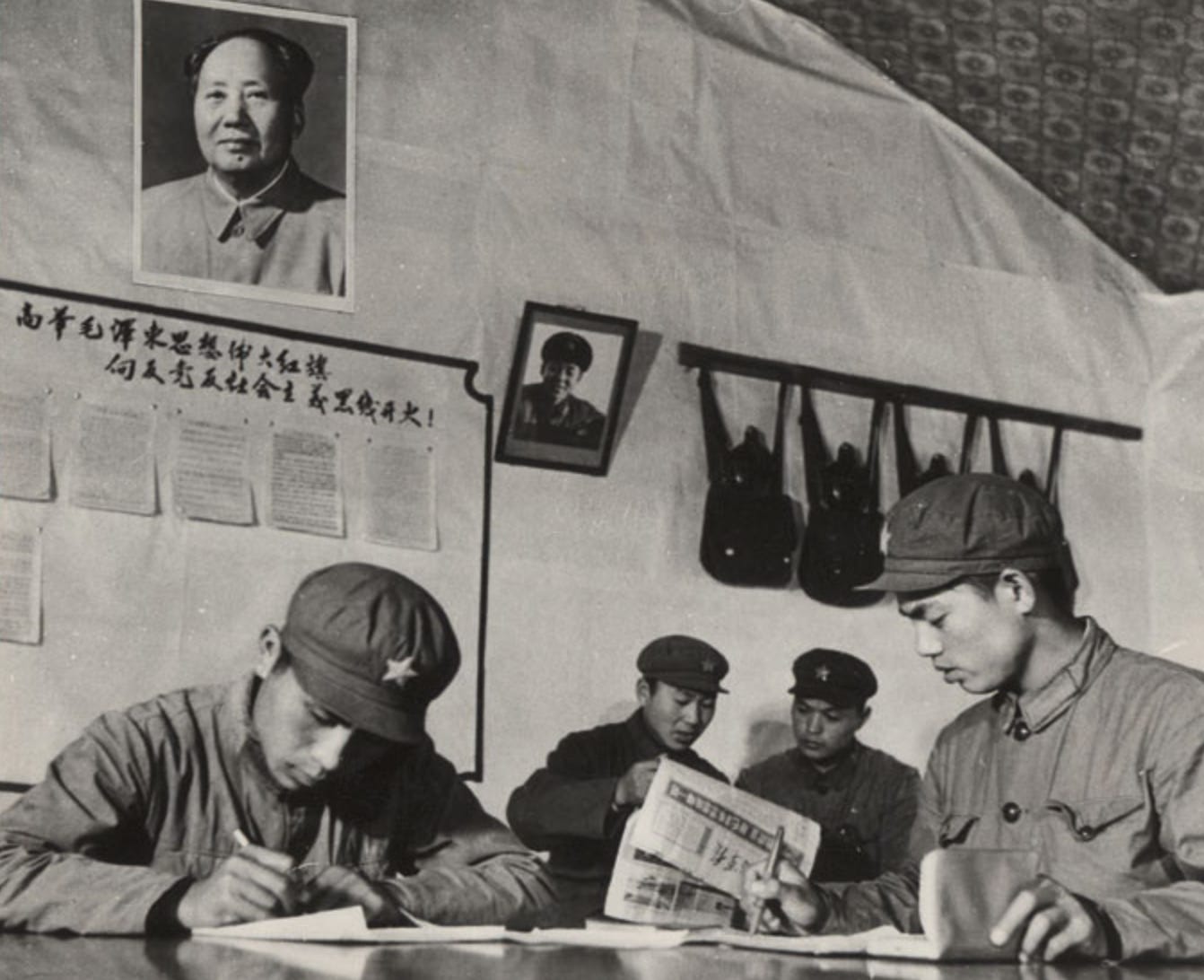

They appear to have thought that Mao was easing into retirement. Instead, he was preparing for the Socialist Education Movement—and then the Cultural Revolution:

Chairman,

The present conference of Lushan is an important one.

I have already made several speeches to the reduced Committee of the North-West, but I did not have the opportunity to present all my ideas during the meetings of this Committee. I want to set

them down here in writing, for your information. I am a simple man, somewhat after the style of Chang Fei; I have his unpolished side, but not his subtlety. And I do not know whether these lines are of any interest : that is up to you to decide. If my opinions are not apposite, please advise me.

A. The accomplishments of the Great Leap Forward of 1958 are self-evident. According to the Planning Commission, verification of various norms shows that the overall value of industrial and agricultural production rose by 48.4% in 1958 on the previous year; industrial growth was 66.1% up and agricultural growth was 25% up (for grain and cotton it must have been 30%). The resources of the state have grown by 43.5%. Such a rate of growth is unprecedented anywhere in the world, and beats all the established norms of socialist construction, especially if we consider that our country has only a weak economic base and an underdeveloped technology. This experiment of the Great Leap Forward has demonstrated the correctness of the general line, “more, quicker, better, cheaper". This is not only a great achievement for our country, but will exercise a positive long-term effect on the whole socialist camp.

However, when we re-examine the construction at the base which took place in 1958, it appears that in various spheres there was excessive haste; we tried to do too much, we wasted part of our investments, we deferred certain essential tasks, and that is a mistake. This mistake comes basically from lack of experience; the problem was not understood in its depth, and was only noticed at a late hour. And in 1959, far from holding back and exercising the necessary control, we have continued with the Great Leap Forward. As a result the imbalance has not been rectified in time, while new difficulties have sprung up. But since in the last analysis these tasks of construction correspond to the needs of the country, favourable results may finally be obtained a year or two hence or after a longer period.

For the moment there are still gaps and weak points which prevent production from developing in a homogeneous way. For certain products and resources the most essential reserves are lacking, and this renders very problematical the immediate readjustment of these new imbalances. And here lies the core of our present difficulties.

That is why when we make our arrangements for next year’s plan it is absolutely essential first of all to make a serious examination of the situation, one which is based on realistic, firm and stable foundations. Where certain points are concerned in the work of construction of 1958 and 1959, points which it seems really impossible to tackle properly, we must take radical measures and interrupt their execution temporarily. In order obtain some things, we must accept having to renounce others. Without this, the serious imbalances are going to stay with us, and in certain spheres it will be difficult to regain the initiative; this in turn will disrupt the rhythm of the Great Leap Forward and the project of catching up with and overtaking England in four years. And the various difficulties will paralyse the power to take decisions, whatever arrangements the Planning Commission makes.

In 1958 the transformation of the villages into communes was a phenomenon of the greatest significance. Not only was this going to free our country's peasants from poverty once and for all, it also constituted the correct path from socialism to communism. Of course there was a period of confusion where the problems of ownership were concerned, and there were gaps and errors in the work itself. All these things were serious, but the successive conferences of Wuchang, Chengchow, and Shanghai made fundamental readjustments, so that these symptoms of disorder are now a thing of the past, while there is a gradual re-establishment of the orthodox path of remuneration according to the labour supplied.

The Great Leap Forward of 1958 solved the problem of unemployment. In a country as densely populated as ours, and with such a backward economy, the rapid solution of this problem is no small matter, it is a considerable achievement.

In the mass mobilisation for the manufacture of steel, the spread of small improvised blast furnaces involved a wastage of resources (raw materials, investments and workforce), and this has naturally been a considerable loss. But we managed to forge an experiment at a nation-wide level, we trained a good number of technicians and the great majority of cadres were tempered and toughened by this movement; of course, this training cost us a lot (two billion yuan), but in a sense it won't be completely useless.

Simply by examining some of the points made above, we can state that the results are considerable but also that they carry a large number of harsh lessons of experience which it would be useful and necessary to analyse thoroughly.

B. How can we draw the conclusions from these lessons of experience? The comrades participating in the present conference are in the process of re-examining the lessons of experience acquired on the job, and they have already got together a large number of useful ideas. The current debates will be extremely advantageous for the work of our party. They will enable us to regain the initiative in several spheres and to grasp the principles of socialist economics better, so that the imbalances which have appeared constantly so far can be rectified, while the concept of positive equilibrium will at last be correctly understood. In my opinion, some of the deficiencies and errors which appeared during the Great Leap Forward of 1958 were inevitable. As with all the movements which our party has directed for more than thirty years, considerable results are necessarily accompanied by deficiencies : they are two sides of the same coin. At the moment the main contradiction which we are faced with in our task springs from the tension created in all spheres by the phenomenon of imbalance. By its very nature, the development of this situation is already affecting relationships between peasants and workers and between the various layers of the urban population. As a result, the problem now is of a political nature, and will affect our ability to mobilise the masses into continuing the Great Leap Forward.

In the past, the deficiencies and errors which appeared in our work had multiple causes. Among the subjective factors we must place our lack of familiarity with the work of socialist construction, the incomplete nature of our experience, our superficial understanding of the balanced and planned development of socialism, and the insufficiently thorough and concrete application of the policy of "walking on two legs". When it comes to making decisions in the sphere of socialist construction, we are as a whole still far from possessing the sureness of touch which we possess in the political sphere (when it comes, for example, to bombarding Quemoy or pacifying the Tibetan rebellion).

And as far as the objective factors are concerned, our country is in a state of destitution; there is still a large part of the population which does not eat enough to satisfy its hunger, and last year the distribution of cotton cloth was only eighteen feet per person, enough to make a shirt and two pairs of trousers. Our country's backwardness arouses urgent demands for change from the populace. To this we must add the favourable developments in the internal and the international situations. All these factors made us rush the Great Leap Forward. And the idea of taking advantage of a good opportunity to meet the aspirations of the masses, to accelerate our work of construction and to transform the destitute and backward state of our country as quickly as possible, in such a way as to create an international situation that was even more favourable: this was a rigorously correct and necessary idea.

Several problems have appeared in our way of thinking and our working methods, and they deserve to be mentioned. They are mainly as follows.

1. Resorting increasingly to empty boasting. Last year during the Peitaiho conference, the statistics for food production were overestimated; since these false premises had given us the illusion that the problem of food production had already been solved,we then tried to tackle industry. But where the development of the iron and steel industries was concerned, we had only a dangerously partial knowledge of the problems; not one person made a serious analysis of the equipment necessary for smelting the steel or crushing the minerals, and no one studied the problem of fuel, raw materials and transport capacity, or the problem of increasing the workforce, or the buying power or management of the market.

In short, the project lacked even a rudimentary balance, and reflected a total absence of realism; at the source of it all we find this habit of making empty boasts which has invaded all the regions of the country and all sectors of activity. The newspapers and journals describe truly incredible miracles, and this threatens the prestige of our party. To read the reports which flowed from all sides at the time, one would have believed that the advent of communism was just around the corner, and this went to the heads of a large number of comrades.

Alongside all the boasting about food and textile production and the campaign for iron and steel production, wastage and the blind use of limited resources are spreading. The autumn harvest was a slapdash affair; without taking into account the question of the expenses of exploitation, we began to live at a level which the resources of the country in no way justified. The most serious thing was that for a considerable length of time it was difficult to get any exact knowledge of the situation; and until the Wuchang conference, and then in January of this year the conference of provincial and municipal secretaries, the whole reality of the situation had never been completely exposed.

These crude boastful habits have social roots and would repay serious analysis; they are connected with this habit we have of assigning norms for all tasks, but without following them up with concrete steps for their execution. Last year the Chairman indeed gave the whole party instructions to combine a "zeal which shakes the heavens" with a scientific spirit, and to observe the policy of "walking on two legs"; but in fact it seems that these precepts have still not been understood by the majority of leading comrades, including myself.

2. The petty-bourgeois hot-headedness which too easily inclines us towards leftist errors. In 1958, during the Great Leap Forward, many other comrades and myself allowed ourselves to be intoxicated by the results of the Great Leap and by the fervour of the mass movement. The leftist tendencies grew considerably. In our impatience to find a short cut to communism, our desire to forge ahead put everything else into the background, and we forgot the mass line and the pragmatic style which had traditionally been typical of our party. In our way of thinking we began to confuse strategy with concrete executive measures, long-term policy with short-term dispositions, the sum and the parts, the whole collectivity and particular collectivities.

Thus the slogans launched by Chairman Mao, "sow less to harvest more" and "catch up with England in fifteen years", applied only to strategy and long-term policy. We sinned by failing to reflect; we did not pay enough attention to the specific conditions of the moment. Instead of setting our tasks on a positive, firm and solid footing, instead of raising the norms gradually, we suddenly fixed a target of a year or even a few months for tasks which would normally demand several years or even ten years or more. And that is how we came unstuck from reality and alienated ourselves from the support of the masses.

For example, we prematurely dropped the principle of exchange at par, and we prematurely promised the notion of free food. In regions where the harvest seemed to be good, we temporarily abandoned the normal sales outlets and began to gorge ourselves. Certain techniques were inadvisably made general without having been tested first; we rashly did away with economic laws and scientific principles. There you have more examples of this leftist tendency.

In the opinion of some comrades, giving "priority to politics" is a universal panacea. They forget that to give "priority to politics" also means to raise the consciousness of labour, to guarantee tb' quantity and quality of production, to give free play to the positive energy and creative genius of the masses, and thus to accelerate the socialist construction of our economy. "Priority to politics" cannot be substituted , for economic laws, and above all it cannot replace specific measures for executing economic tasks. To the principle of "priority to politics" must be added really effective measures concerning our economic tasks; these two aspects must be the object of equal attention, and neither should be given the advantage to the detriment of the other.

As the historic experience of our party teaches us, the rectification of these leftist tendencies can prove tougher than the fight against conservative and rightist thought. Over the last six months of last year, there seems to have been an atmosphere in which everybody's attention was fixated on conservative and rightist thought, and this meant that the problem of subjectivism was neglected.

Since last winter, with the Chengchow conference and all the measures which stemmed from it, several of the leftist tendencies have been rectified, and this constitutes a great victory. This

victory has served as a lesson to the members of the whole party, without affecting their positive energy. Now, as regards the country's internal situation, we can basically see our way clear. Especially since the recent series of conferences, most of the comrades in the party have basically come to share the same point of view.

Our current task is to unify the party as a whole, and to continue to work keenly. It seems to me that it would be a good idea to draw up a systematic balance-sheet of all the results and lessons which we have had since the middle of last year, in order to enlighten the comrades better in the party as a whole. The aim of such an undertaking would be solely to establish a clear distinction between truth and error, to raise the ideological level, and in no way to identify the individuals responsible, which could only threaten our unity and our work.

As regards the problems which are due to our lack of experience with the laws of socialist construction, some have been solved as the result of experiences and re-evaluations that have taken place since the middle of last year; as regards others, we still need a certain period of study and of feeling our way before we can master the answers. As regards ideological problems or those concerned with our way of working, present experience has entailed a harsh lesson which has already somewhat woken us up.

But while it is really a question of making radical amendments, it will still be necessary to make a stubborn effort. As the Chairman indicated during the present conference, "the results are considerable, the problems are numerous; we have acquired a rich experience, we have a bright future." In order to regain the initiative, our party must unite; once it shows itself able to fight with spirit, the requisite conditions for continuing the Great Leap Forward will exist. This year, next year and for the coming four years of the new plan, it will be necessary to round off the victory. The aim of catching up with England in fifteen years can essentially be resolved in the next four years, and where certain products are concerned we can certainly surpass England: such are our considerable results, and such is our bright future.

Please accept my respectful greetings.

Peng Dehuai

14 July 1959

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)

It was clear that China changed gears around 1960. Before then it was empty slogans and disasters. Mao wanted to build a nation, but while he understood the politics, he did not understand the necessary mechanics of development. The 1960s, for all the revolutionary fervor, the purges and internal challenges, saw the systematic introduction of modern technology. When I read Smil's account of China bringing in a Dutch firm to build a Haber process plant for nitrogen fixation, I was surprised, but this was probably just one piece of the modernization process.

I know Qian Xuesen returned to China in 1955 to work on China's nuclear program. He's still a revered figure since his systems approach, measuring inputs and outputs, is still a driving force in China today. He had been a student of von Karman's at Caltech, worked at the Manhattan Project, and was at JPL when the Americans sidelined, arrested and later deported him. It appears that things were changing even before the 1958 conference. Now I'm wondering who sponsored his return.