DRAFT: For My Wednesday Night Lecture: Social Theory for þe 21st Century

I gotta cut this in half, somehow, before Wednesday night; 2023 Navin Narayan Memorial Lecture; Harvard College Committee on Degrees in Social Studies; Cambridge MA.

The punchline of my lecture today is: Machiavelli, Smith, de Tocqueville, Engels, Lenin, Luxemburg, Weber, Durkheim, Freud, de Beauvoir; Keynes, Schumpeter, and Polanyi; Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, and Ta-Nehisi Coates, Benedict—not Perry—Anderson, Gellner, and an economist named Richard Baldwin; historian Gary Gerstle; Arendt; and closing out with Debord, Foucault, and something I hope my colleague Marion Fourcade will someday write on the society of the Spectacle and the Algorithm.

(1) You and I are here assembled for the annual 2023 Navin Narayan memorial lecture in social studies, given in memory of Navin Narayan, a summa cum laude Social Studies graduate who died in the year 2000 at the age of 23 of a cancer. Now it is right and proper that we do this as an act of ritual, and as an act of work.

Since 1965 there have been perhaps 200 people graduating from Harvard summa cum laude in Social Studies. To do so, you have to (a) do very well, and (b) be lucky, overwhelmingly lucky, enough so to have thesis readers who really really like your thesis. I am eternally and extravagantly grateful to Professors Peter Hall and Gerry Friedman for liking my undergraduate thesis enough to push it over the line.

Along that dimension, at least, I am thus very close to Navin Narayan: 110 billion people have lived since the year –50,000; 200 with Harvard B.A.’s summa cum laude in Social Studies. We summa graduates are thus 1/500,000,000 of the human race. With his saddening and premature death, there is a gap that is very close to where I stand in the ranks of humanity.

With every death: the appropriate reactions are threefold: (a) we mourn, (b) we contemplate that death comes for us all when it chooses and we reevaluate our priorities, and (c) we see that there is work to be done that the one of us we have lost was doing and now cannot do, and so we take on the load. It is for us the living to be dedicated to Navin Narayan’s unfinished work. And this lecture is, if it works, a step forward in accomplishing that work.

So what is Narayan’s work? What is our work?

(2) Look around: the overwhelming majority of it are associated with an organization called the Harvard College Committee on Degrees in Social Studies–are members of that group. Now it is the first truism of humanity that on our own we are pretty incompetent: unable to accomplish pretty much anything. But in groups we are powerful. Author Kurt Vonnegut had this idea—a joke-but-not-a-joke—of a thing called a karass–a human group that was assembled, but not by their or anyone else’s deliberate choice, to carry out some piece of work. I remember George Akerlof wooing me to come to U.C. Berkeley because, he said, he and the other professors there were in my karass. Consider the group of people around Social Studies in that light.

What then is the work that we have been assembled to do?

It is no secret. We have been assembled to try to make progress in understanding human society, and then to ourselves and with the assistance of others we persuade to work so that our deeds in the present create a brighter and better and more human future. The founders of Social Studies 60 years ago were groping toward a plan for how to do this. They were, first of all, envious of how the History and Lit major gained and spread insights and knowledge in the humanities via “creative trespassing”, and they sought to do something similar in the social sciences, guided by five beliefs:

That the disciplinary structure of Social Sciences is an iron cage…

That the history of how we got here matters…

That “social theory” matters as well–everyone has one, for we cannot think about society at all without one…

But social theory can be your tool rather than your master only if you gain a critical distance on your own social theory…

And the best way to gain that critical distance is through intensive focus on the creative-trespassing “classics”…

But what are these “classics”? And which of the potential candidate “classics” are truly useful for understanding our society, the society we live in today and will live in tomorrow?

So now I have finally reached my topic: We are assembled here today in memory of Navin Narayan to advance the work of a karass that he was part of: to understand as much as we can of human society, so that we can do our deeds in the present to create a brighter and better and more human future.

But in order to do that we first have to guess which “classics” of social theory we should read and study to best equip us to understand human society.

(3) And so we retreat to a prior question: what is it about our human society that we need to understand? What puzzles us about it?

Let me shift gears, and approach that question indirectly:

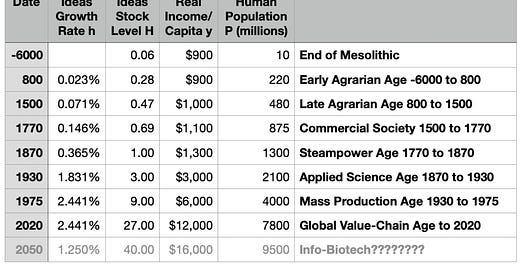

Since I am a card-carrying economist, I cannot give a lecture without putting up numbers. So here are my guesses about the longest-run eagle’s-eye view of the human economy over the past 8000 years:

Column 1: The date.

Column 5: human population, growing from 10 million in the year –6000 at the end of the Middle Stone Age to 480 million at the end of the long Agrarian Age in the year 1500. Thereafter human population grows faster: to 1.3 billion in 1870 at the end of the Steampower Age, explodes to 7.8 billion in 2020, and will, we think, stabilize around 9.5 billion in the middle of the century of the 2000s.

Column 4: Our guesses at what average real annual income per capital was for humanity: near-dire poverty–barely above the World Bank’s dire-poverty threshold of $2.50/day–with more than half of typical incomes going to get 2000 calories plus essential nutrients a day, enough shelter that you do not frequently find yourself drenchingly wet, enough clothing and fire that you are not frequently shivering cold–from –6000 up until 1770 or so. A little progress in raising incomes from 1770 to 1870, but only a little. As late as 1871 John Stuart Mill was writing and publishing that all mechanical inventions hitherto had done little more but enable a greater population to live the same life of “drudgery and imprisonment”. Not just in an iron cage, but forced by material want to labor on a treadmill as well.

After 1870: an explosion of average income, albeit an explosion extraordinarily and astonishingly unequally distributed around the world.

Column 3: I assert that humanity’s major… I don’t want to say “patrimony”, and “matrimony” has a very different non-analogous meaning… than humanity’s major treasure and possession is our inheritance and acquisition from others of useful ideas for manipulating nature and coöperatively and productively organizing ourselves: our “technology”, in the broadest sense. I assert that a quantitative index of this–the value of the stock of human ideas–is roughly equal to average incomes times the square-root of the human population. Why the square-root? Well, if we set “technology” equal to average incomes, we would be saying that resource scarcity is not a thing–that to support a population of 5 billion at a certain level of prosperity requires no better technology than to support a population of 50 million. That cannot be right. Well, if we set “technology” equal to total incomes–population times average incomes–we would implicitly be saying that extra hands and eyes and brains are not themselves productive. And that also cannot be right. Square root is in the middle.

If we take this index I call H for “Human Ideas” semi-seriously, we see that our quantitative index of technology advanced eightfold between –6000 and 1500, as population expanded 48-fold and average incomes barely moved at all. Why? I blame patriarchy. Desperately poor populations without modern publish health see infant and early-childhood mortality rates of nearly 50%. And you were not home-free if you survived to age 5. A typical woman with 8 pregnancies carried into the third trimester would have only two of her children survive to reproduce, and would have one chance in three of reaching late-middle age–if she reached late-middle age–without a surviving son. In a highly patriarchal world, that is not social death, but it is not that far from it. Hence wherever there were extra resources, people would try to have more children in order to raise the odds of a surviving son. And so from –6000 to 1500 as technology increased people used the extra resources they produced to have more children, and so population grew and farm sizes shrank.

Driving this ensorcellment of humanity by the Devil of Malthus was the extraordinarily slow rate of Agrarian-Age growth in technology. Look at column 2. 0.023%/.year as the growth rate of human technology in the Early Agrarian Age? We get more technological progress in a year than they got in a century.

And, of course, after 1500 the ice breaks. Triple watershed-boundary crossings–from the Late Agrarian Age to Imperial-Commercial Society around 1500, from Imperial-Commercial Society to the Steampower Age around 1770, from the Steampower Age to what Simon Kuznets called “Modern Economic Growth” around 1870–see a doubling, then a near-tripling, than a near-quintupling of the pace of technological advance. They see a population explosion and then, as humanity grows rich enough and gets good enough public health for infant mortality to decline, the demographic transition from a typical level of 8 down to 2 pregnancies, and the creation of the societies that we see today.

Desperate poverty and extremely slow change from –6000 to 1500. The ice breaking in various ways over 1500 to 1870. And technological explosion producing an enormous if very ill-distributed increase in human wealth coupled with a population explosion and the demographic transition after 1870–that is the longest-run eagle’s-eye view of the history of the human economy.

And this table instantly raises many follow-up historical questions: How did our changing “forces of production” both enable and constrain the kinds of societies we built? Why was economic “progress” so slow in the Agrarian Age? What possibilities were unleashed by the coming of the Imperial-Commercial, Steampower, and Modern Economic Growth ages, respectively? And how were those possibilities (and dangers) handled?

(4) Well, six months ago I published a book about the last of these–how were the possibilities (and dangers) unleashed by the arrival of Modern Economic Growth handled? It is called Slouching Towards Utopia: The Economic History of the Twentieth Century <bit.ly/3pP3Krk>. I am extremely gratified at the number of people who have liked it, and I am even more pleased by the people who have taken it seriously and taken issue with it. Indeed, finding films and critics in such large numbers has been one of the highlights of my life. I have found myself annoyed by reactions to the book only twice Dash from Britain’s telegraph, and from the trompist Claremont review of books it was not that they disagreed with the book, or even that they thought that the proper use of ideas is not to understand the world, but rather to be used as political weapons for advantage, but rather yellow that they thought slogans should take the place of ideas. Perhaps the most astonishing thing about it is that I convinced mass-market publisher basic, who is comfort zone is a book of 350 pages to publish a book of 624. I’m more than half thought they would ultimately tell me to go away and find some university press somewhere.

My book doubles down on the claim that 1870 was the hinge of history. Before 1870 the growth rate of technology was just too slow to overcome the imperative, imposed upon humanity by patriarchy, to devote more resources to trying to have more sons as “insurance”. Those factors humanity from being able to even think of baking a sufficiently large economic pie for people to have enough.

How, then, in such circumstances, with humanity ensorcelled by the devil of Malthus, do you get enough for yourself and your family? To try to become astonishingly productive yourself is very difficult given the resource scarcity caused by the imbalance between technology, resources, and human numbers. And to become astonishingly productive yourself makes you a soft target for others.

No. The quicker, easier, and more effective way to get enough for yourself is to become part of an elite: join a gang. Become one of the thugs with spears (and later thugs with gunpowder weapons), or become one of their tame accountants, bureaucrats and propagandists. Run a force and fraud domination and exploitation game on humanity. Get enough for yourself and your family, and enjoy a full belly, being dry, being warm, and your high culture.

After 1870, however, comes the astonishing technology-driven growth of the forces of production. It is then very clear that soon in terms of generations. Humanity will be able to bake a sufficiently large economic pie for everyone to potentially have enough. With such a large pie, the necessity for joining a force and fraud exploitation in domination gang so you can have enough will fall away.

Yes, there were problems of adjustment and transition. There was constant technological revolution. You could not count on even your parent’s job being there for you to fill, even if you wanted to

But the fall in the required number of pregnancies per woman for the population to replace itself from eight to two was an enormous reduction in a burden that Malthus via biology had imposed on half of humanity. Wealth grew to levels that, at least for middle classes in rich countries, was at levels that previous centuries would have judged as “exceeding the limits of human felicity”. It seemed that all that was left to keep humanity from utopia were, now that the problem of baking a sufficiently large economic pie was about to be solved, the less difficult second order problems of slicing, and tasting the pie: equitably distributing our wealth, and utilizing it wisely and well so people feel safe and secure, and are healthy and happy.

But it did not work. We manifestly do not live in a utopia. Killer robots right now stalk the skies over Ukraine and Syria. A great many people around the globe are very upset that others have more than they deserve. And much of the ingenuity of our technologists has been turned to figure out how to algorithmically scare the s*** out of people so that their eyeballs can be glued to screens, and then sold to advertisers of fake diabetes cures and crypto grifts. I could go on. This is not near utopia. But many people in previous centuries would look at you and say: What do you think you are doing? You have solved the big problem – the one that most flummoxed us.

So now we have an answer to our question: What is it about human society that we need to understand? What we need to understand is why slicing and tasting are proving less tractable problems than baking a sufficiently large economic pie.

This state of affairs is where we must work. To repair this state of affairs is what our deeds must do in the present to make a brighter, happier, better future for humanity. To advance the work of the karass of Navin Narayan he need to understand why our human society which is solves the problem of baking a sufficiently large economic pie is totally flummoxed by the problems of slicing and tasting it.

(5) The forces of production of the Agrarian Age–let us center ourselves, say, in Western Europe around the year 1000, in the heartland of the feudal system–created opportunities and imposed constraints on society. Technological progress then was so slow that you almost surely could not distinguish your job from that of your great great grandparent, or of someone’s great great grandparent. The division of labor was not very well developed: for the overwhelming bulk of humanity. They could raise their own food – and the food of the elite upper class as well–with only limited assistance from others’ providing them with tools and conveniences. Overwhelmingly, what obligations and duties you had were imposed on you by the role in society into which you were slotted: as one who works, one who fights, or one who prays. And, overwhelmingly, what rights and privileges you had were also those of your slot.

And as for society in the feudal age, what was there to understand? Emperor, barons, knights, bishops, priests, the occasional clerk, craftsmen, serfs, and the occasional free-status franklin, merchant, and townsman were what they were. There was very little sense that emperor Otto III of the Saxon dynasty was in any real sense a different thing from Charlemagne two centuries or, indeed, Caesar Augustus of ten centuries before.

Feudal-era forces- and relations-of-production thus taught people that society was static, hierarchical, with who you are chosen for you by the role ascribed to you; that production was small-scale, handicraft, and individually autonomous; and that those who work owed rent to those who “protect” them, and tithes to those who guide them to salvation. Hence the feudal mode-of-production requires that we write feudal-society software for society to run on top of it.

But the Agrarian Age came to an end. Technology moved on and commerce grew. Come 1700 it was clear that there was such a thing as society because things had changed: Western Europe, at least, was no longer a feudal, but rather a commercial society. Moreover, it was an imperial society. On the imperial side, Niccolo Machiavelli wrestled when he hoped to get a job working for the Medici (in part, because then he was pretty sure they would stop threatening to torture him) with the problem of creating a new state. At other times he wrestled with how a non-feudal urban republic could hold itself together. Thomas Hobbes tried to figure out how there could be a state and a society at all when you could no longer claim divine authority for a hierarchical organization that at least appeared to be what it had been in your great-grandparents’ day.

Commercial-imperial gunpowder-empire forces- and relations-of-production, by contrast, teach people that society is mobile, contractual, with who you are chosen by you if you can make a contractual-network place for yourself; that production is middle-scale, aided by tools and finance, and interdependent; and that we all owe each other a peaceful world in which we can make and fulfill the bargains and contracts our interdependence requires. It taught the bourgeois virtues. And it worked, more or less. It had taken 700 years for the forces-of-production to transform themselves from their feudal-agrarian to their commercial configuration, and thus adjustment had been–mostly–gradual.

Read the social theorists of commercial society–John Locke, Adam Smith, Immanuel Kant, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel have shown up on the Social Studies 10 reading list–and they see a good society, in which only feudal survivals distort and disturb the picture. And they read to me like before-day Franks Fukuyama: confident that institutions have reached their culmination point, and that there is or is about to be an End of History. Only–from the reading list–Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Mary Wollstonecraft are disturbed. Why the subjection of women? And how can humanity be unified so that the general will appears as a liberator rather than an oppressor?

But they were wrong. Commercial Society was not the End of History.

(6) Technology moved us into the Steampower and Machine Age. It was not only modes of production and distribution that mattered. Modes of communication and domination mattered as well.

Printing revolutionized the means of communication–had done so profoundly, in fact, even before the 1500 end of the Agrarian Age, with profound consequences. Textile and further forms of automatic machinery revolutionized manufacturing. Most of all, there was the steam engine, huge, honking, noisy, dirty, delivering immense power and herding us all into large factory-building workplace for only there could we have access to the power of the magical machine that was the steam engine.

Friedrich Engels of Barmen and Manchester saw the implications of technological development and modern science: that soon the economic pie would be sufficiently large for everyone to potentially have enough. Moreover he thought he saw more. In a Steampower and Machine Age, the simple act of going to and working at our workplaces would teach is that:

society is collective, and that we are massively productive.

individually we are unproductive, for the source of productivity is the technology and the division of labor it enables.

we are valuable only to the extent that we do slot ourselves into a place in the industrial world’s complex division of labor.

production is social in which none of us can claim to have produced anything

each of us is both essential and unnecessary–essential in the network, but unproductive outside of it;

And Freddie from Barmen thought, roughly, that this steampower-machine industrial experience would teach us that:

we all owe each other a recognition of our common equal humanity and contribution in a free society of associated producers.

we all want to dress in identical blue denim overalls.

we all will enthusiastically call one another: “Comrade!”

we will rotate through the administration and coordination jobs, which have been greatly simplified by modern management science.

And in the process the government of men–i.e., running and maintaining the force-and-fraud exploitation-and-domination scheme–would be replaced by the administration of things–simple ministerial acts of coordination, boring in that they required that one be an accountant rather than exercise one’s powers to create. There were, Engels thought, great stresses of adjustment. From Commercial Society to Steampower Age had taken only 150 years compared to the 700 from Feudal to Commercial Society, and the 1500–17000 Wars of Religion had been no picnic. But to Engels the future was certain, and bright. All would be well. Now that we were actually at the End of History

But, of course, Steampower and Machine Society was not the end of history either.

(7) Engels was, of course, wrong.

The Steampower and Machine Age passed away, so whether the practice of work under it would have ultimately taught humanity the socialist lessons that Engels thought it would have taught is largely beside the point. Globalization meant industrial processes shook economies and societies continents away. Science, in the industrial research lab and the modern corporation, brought a massive speed-up in technological growth in the rotation in of new leading sectors: chemical engineering, advanced materials, internal combustion, electricity, radio, aviation, and more. The Steampower and Machine Age was succeeded by the Applied-Science Age, which was succeeded by the Mass Production Age, which was succeeded by the Global Value-Chain Age, and we are now launching ourselves into what I think will be the Info-Biotech Age.

The modes of production and distribution, communication, information, and domination in each of these taught different lessons. The globalized market economy of the Applied-Science Age brought with it rapidly increasing global inequality across nations to be added to growing inequalities between proletarians and capitalists. And proletarians ceased to all be proletarians with the rise of “labor aristocracies”. That some sectors were leading and other sectors trailing, that governments’ turned out to have powerful tools to create and manipulate sector-level income differentials, that social Darwinism arose first as a way of justifying the plutocracy’s wealth to itself and others and then spread so that it became a commonplace that the most important differences that needed to be maintained were those of biological race–all these meant that Applied-Science society taught people different lessons about “social justice” than Steampower Society. Engels thought Steampower Society would teach us all that we were all equal, and equals should, in justice, be treated equally. But what if relations of production, distribution, communication, and domination taught us that we were not equal? What then? Well, you get people who could really benefit from Medicaid expansion in their state who vote for Donald Trump because he will end the ObamaPhone program by which shirkers and lazabouts get, in Senator Mitt Romney’s words, “free stuff”, and in return provide the illegitimate votes that got Obama into the Oval Office. Never mind that the free cell-phone problem is a George W. Bush administration program originated by people in his administration seeking for administrative efficiencies in communication, who perhaps took campaign lines about a “compassionate conservatism” seriously,

Steampower to Applied Science, Applied Science to Mass Production, Mass Production to Global Value-Chain, Global Value-Chain to Info-Biotech–all of these transitions were certainly as big and important in amplifying human technological prowess, and arguably as big and important in transforming human work practices, as were the transition from Feudal to Commercial and Commercial to Steampower. But all of these took not 600 years of 200 years but a mere 40. And the principal cleavages–the fights over distribution and utilization–while they were often property rights against other rights, they were rarely bourgeoisie vs. proletariat. Indeed, they seemed to be everything but.

Schumpeterian creative-destruction revolutionized the economy every generation. Schumpeterian creative-destruction created immense wealth. Schumpeterian creative-destruction destroyed firms, jobs, occupations, livelihoods, communities. The failed experiment of Really-Existing Socialism from 1917–1990 convinced everyone that Friedrich von Hayek was right: we really did need to have the market economy to crowdsource the problems of managing our immensely complex division of labor. But the only rights the market vindicates are property rights. And that ordering of society creates, in Karl Polanyi’s phrase, “a stark utopia” that is profoundly unfit for humans, and that humans would not long stand for.

Off in the corner you have John Maynard Keynes, whimpering, saying that if only you let his technocratic students manage things, interest and profit rates will be so low that plutocracy is a bearable burden, and unemployment will be so low that everyone’s willingness to work will be a valuable form of property and give them wealth that the market will then vindicate. But policies biased toward full employment bring on at least moderate inflation. And even moderate inflation is seen by nearly everyone as a breakdown of government competence and a violation of the contract between the government and the people.

How to cobble together rewritten software code for society on the fly so that it does not crash as the underlying forces-of-production hardware changes? And how to do this in less than 40 years, and do it again in the next 40 years?

Those were the problems that have flummoxed humanity since 1870, and have left in unable to equitably distribute and wisely use our wealth. Those are the problems we need help with. And we need help with them as much today as people did at any time in the past 150 years.

(8) Let me pause and shift gears again:

In the spring of 1993 my longtime friend, patron and coauthor went down to Washington DC to be Undersecretary of the Treasury for International Affairs. And I went down with him and all the others to be a Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury for Economic Policy, working for Alicia Munnell, best of all bosses. I quickly found that my social studies education seemed to be very useful and on point, but really… not. I was ideally prepared to be aDeputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Economic Policy. If it were sometime in the period 1900–1940. And if it were someplace in Western Europe.

It was not: it was 1993, and it was the United States of America.

It was not, precisely, that it was useless to build on the social theorist. I had read in social studies 10. The problems of political organization when you could not retreat to established hierarchy, time on earth, unchanging practice, and God—those remained. Those were what Machiavelli and Hobbes had tried to grapple with. That remained of value. Other Commercial Society theorists who had grappled with the problems of life in a commercial, network, exchange, contract society, in which the greatest of all contracts to be written had to be the social contract—those problems remained, and insights remained. The theorists who confronted Steampower and Machine Age Society had insights into how not just technologies of industrial production, but those of mass communication, mass distribution, and mass domination imposed requirements on how society’s relations-of-production and superstructural sociological, political, and cultural software needed to be rewritten. And the post-Marxists Weber, Durkheim, and Freud who had lived in the Applied-Science Age—they were useful too.

But there the Social Studies curriculum seemed to stop. I do remember being told back when I was a freshman here that Barrington Moore’s Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy was the quintessential Social Studies book. Its focus was on how social, economic, and political development had gone badly to the totalitarian right in Germany and Japan, had gone badly to the totalitarian left in Russia and China, had gone well in France, Britain, and the United States, and appeared to have a good chance of going well in India. Social Studies as the Barrington Moore problematic was set in the 1950s by people who had lived through the 1930s and 1940s and were oriented toward Europe. So even Mass Production lay largely outside their field of vision, as did decolonization, post-colonialism, the Global Value chain economy, the current move into Info-Biotech, the successes and then the fall of the New Deal Order, and the rise of Neoliberalism.

Now it is not that the Social Studies faculty has sat on its hands over the past 60 years. Theorist after theorist has been added to the reading list in the hope of finding someone who can stand next to Hobbes, Smith, Mill, Marx, Weber, and Durkheim while also offering insights into paths toward analyzing societal-scale phenomena of which they could not even dream. But picking such who will be useful to students is a very difficult task. And the task becomes even worse when we reflect that students entering high school next year will turn 40 in 2050, and so will be trying to make their way as citizens, producers, and providers in a world in which Info-Biotech Age forces of production may well themselves be beginning to be seen in the rear view mirror.

(9) But I have to say something. I did say at the start that I would summon the Owl of Minerva. So let me at least try:

There is wisdom in Machiavelli, both in the establishing of a New State of Affairs in The Prince, and in running a participatory polity that somehow pulls together when so many cleavages are tearing it apart in the Discourses. The Prince is short. The Discourses are repetitive in theme, hence very, very excerptible.

For the market economy as a piece of magic for crowdsourcing human solutions to society’s problems—as a genuine addition to the social mechanisms of reciprocity, redistribution, democracy, hierarchy, and prestige/honor that humanity had previously had on its menu of potential mechanisms for self-organization—you have to have Adam Smith. And not the Smith of Book V and of the Theory of Moral Sentiments that Social Studies tutors love: the Smith of Books I, II, and IV—of the power and the utility of the market system, and how you get crosswise to its logic at your society’s peril.

What Smith does for the market economy Alexis de Tocqueville does for modern democracy—with special bonus insights into absolutism, bureaucracy, and Cæsarism that are of truly great value. I do not care that Raymond Aron singlehandedly smuggled him onto the social theory reading list after World War II for reasons of his own: given our goals, he definitely belongs.

That capitalism starts out good but turns very bad, and is so corrosive that you dare not leave even a fragment of private property in existence–that is Marx. Lenin, Mao, and Castro’s warrants were legitimate, with Marx’s true signature and seal on them. That is a rabbit hole it is not worth sending students down.

Thus Charlie from Trier belongs on the reading list only for the things he co-wrote with his best friend Freddie from Barmen. But what they wrote together, and what Engels wrote on his own–there is a lot of gold in them thar hills. “All that is solid melts into air”. That it is science and technology that are the key tools of the Dialectic for progress, that the forces of production as they shape the way we work and live teach us powerful lessons about how to organize society that we cannot ignore–those are treasures for all time. Do balance him, however, with Vladimir Lenin’s State and Revolution, which is a better sketch of Engels’s utopian visions than Engels himself ever wrote down. Yes. Irony. Bitter irony. And Lenin must in his turn be balanced by Red Rosa: Rosa Luxemburg’s The Russian Revolution.

Weber on bureaucracy, modes of domination, and the iron cages we construct for ourselves; Durkheim on solidarity, on how we are perhaps least free when we do exactly as we think we want to, and on the distorted mirrors in which we view ourselves and society; Freud on how jumped-up East African Plains Apes too dumb to reliably remember where they left their keys last night cannot have reliable insights into their own mental processes–yes. Freud’s death instinct can perhaps start us thinking about why WWI. But not at length. A curriculum that stops with WWI is for historians, not for those who seek to understand the world so that they can change it.

Simone de Beauvoir, in my estimation, remains in a class of her own.

For the issues raised by the arc of history in the North Atlantic from the breakdown that was World War I through mass production and social democracy to the breakdown that was the 1970s collapse of the New Deal Order, I choose Keynes, Schumpeter, and Polanyi—but the undergraduates who do not bounce off of Polanyi as incomprehensible and snooze-inducing I have, unfortunately, found very rare indeed.

For nationalism and the place of nations in the global economy, I would balance between Ernst Gellner and Benedict Anderson for the first, and a book by Richard Baldwin, The Great Convergence for the second,

For racism: Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. DuBois, and Ta-Nehisi Coates. Yes, my friend Ta-Nehisi would say, correctly and truly, that he cannot bear an equal share of the weight carried by that company. But I know of nobody better, so I elect him.

Analogously, for the New Deal Order’s fall and the Neoliberal Order’s rise and subsequent vicissitudes, I elect Gary Gerstle.

For revived neofascism, it is the case, still, that no one measures up to Arendt.

And for what we now seem to be moving into? The society of the Spectacle and the Algorithm? Guy Debord, Michel Foucault, and something that I hope my colleague Marion Fourcade will someday write.

Now my colleague Marion—and also my friend Ta-Nehisi, and Gary Gerstle and Richard Baldwin will surely protest, and say that their work is not strong enough to stand in that company. And they may well be right.

But who else? Who better?

That is my reading list for Social Studies 10—the social theorists, explicit and implicit, that they should see if they are to best critically reflect on the social theory they will be using to maneuver as citizens, producers, and providers in the world of 2050. For only if they can critically reflect will their social theory be their tool rather than their master.

The problem is that I really need to cut this down to 1/3 of its current length.

What is your list?

Thanks. Very helpful, especially for people trying to figure out how to understand, how to create a necessarily simplified mental model of a steadily changing reality/system. I think of economics that way too -- not that the old guys were all that far off -- it is just that what they wrote fit their world better than ours. While the talk is tailored for an academic audience and their constant problem of optimizing their reading lists I think many non-academics will enjoy it as I did.

Frankly, this is hopelessly bad. The problem, I think, is you are trying (and keep trying to in varying contexts) to condense your 600 page book into a 30 or 60 minute lecture. It doesn't work. Unfortunately, you don't have time to tear it up and start over. (As the famous quote goes, "This letter would have been shorter if I had had more time to write it.")

Couple of narrow points:

I agree with TLH that:

-- The summa and 1/500,000,000 paras. come across as crass. (In a way, disrespectful to the memory of the lecture's namesake.)

-- This condensation of your book is indeed likely to come across as stuffed with a lot of what is not much more than name dropping. You know what you mean, and readers of Slouching already know what you mean. Others get subjected to a mind-numbing index.