How Much Wealthier Are We Today þan Our Counterparts of the Past

Lecture at (Virtually) St. Stephens College, Delhi, India :: 2022-02-11/12 Fr/Sa

J. Bradford DeLong

University of California, Berkeley/St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi

2022-02-11/12 Fr/Sa

1. Social Science’s Killer App

I was hanging out with my one-time student, Ohio State University professor Trevon Logan. We were outside on the lawn on a beautiful summer’s evening in America’s Pacific Northwest. Trevon reminded me of something that the late economic historian Robert Fogel liked to say:

The killer app of social science is counting things…

Yes, we need to have “thick descriptions”, and empathy and imagination to enter into the minds and world views of those we are attempting to understand.

Yes, we need to have narratives with protagonists; beginnings, middles, and ends; and cause-an-effect—if only because our not-very-smart East African Plains Ape brains find it very difficult to think in any other way.

But, most of all, we need to count, so we can tell which stories and which anecdotes are strange and unrepresentative Outliers in which capture for us common occurrences and major trends.

Thus the overwhelming bulk of this lecture is going to be me trying to count things. And along the way I will try to draw out the implications of that counting. In the process, I am going to try to count things that are difficult to count, and perhaps some things that are uncountable, and perhaps some things that should not be counted, and perhaps some things that are the wrong thing to count. I leave that to you to judge.

I see myself as here more to suggest and to provoke. I do note see myself here to provide anything that is a final, or even more than a preliminary, word.

2. How Much Richer?

How much richer are we, today, than those who came before us? By “we” I understand, first, those of us who sit in universities and watch zoom calls; second, those with whom we share our respective allegiances to the fictitious communities—but very real communities—that are nation-states; and, third, the entire human race, all of us who all draw the overwhelming bulk of our heredity from some 4,000 lucky East African Plains Apes 75,000 years ago living in the Horn of Africa, who have sense spread out around the world, intermarrying along the way with other groups of homo sapiens and groups from other human species that we found along the way.

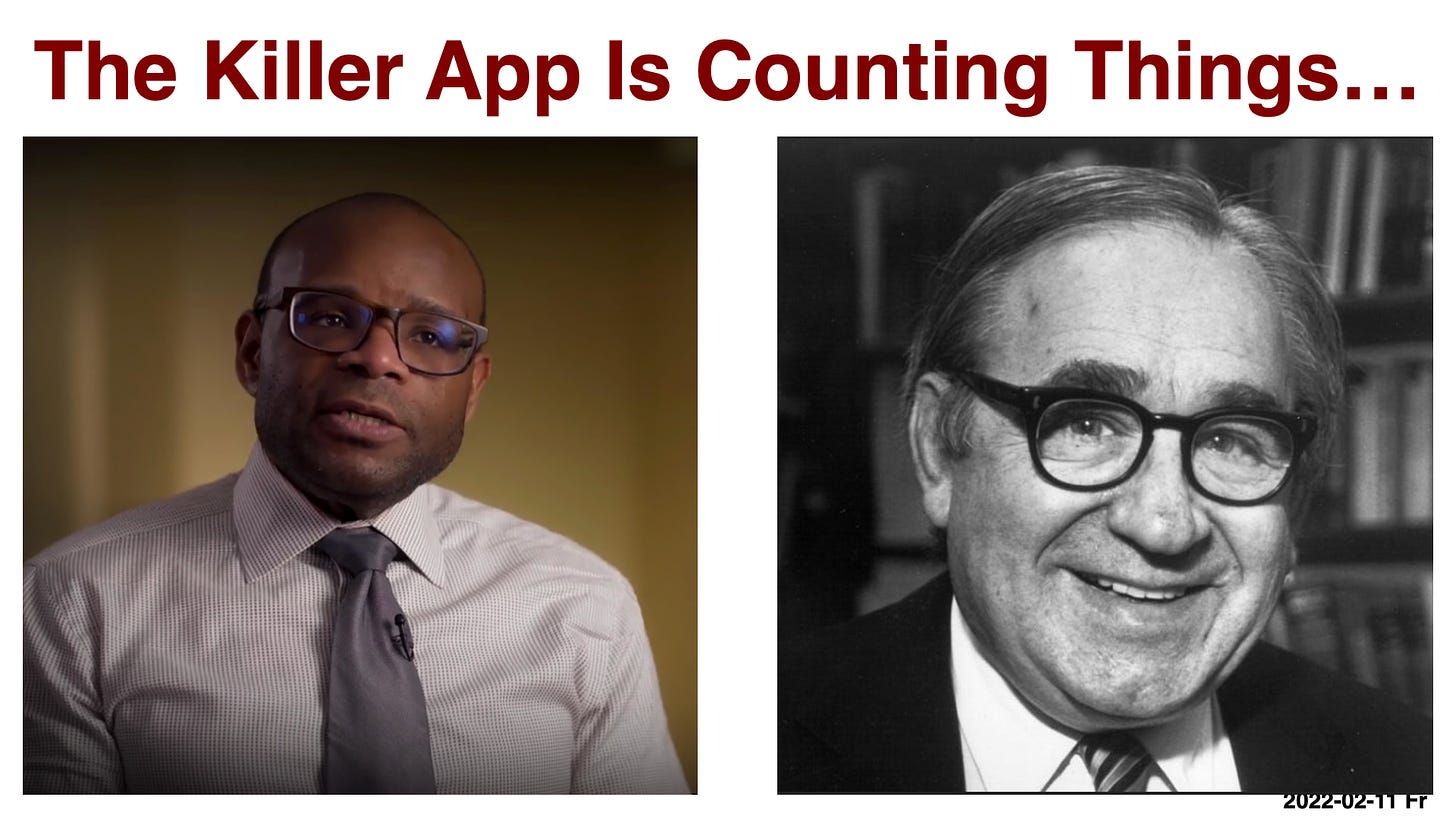

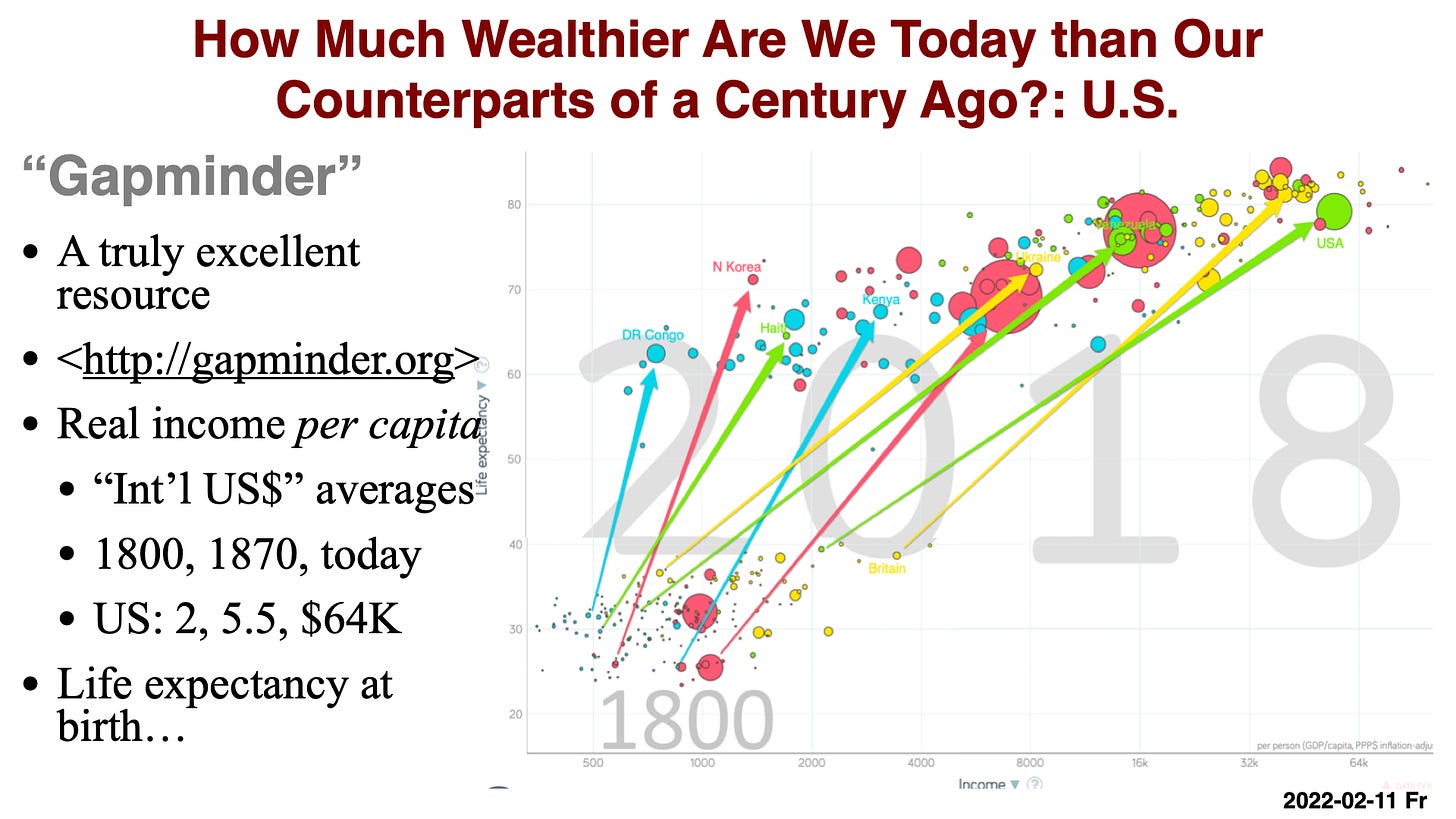

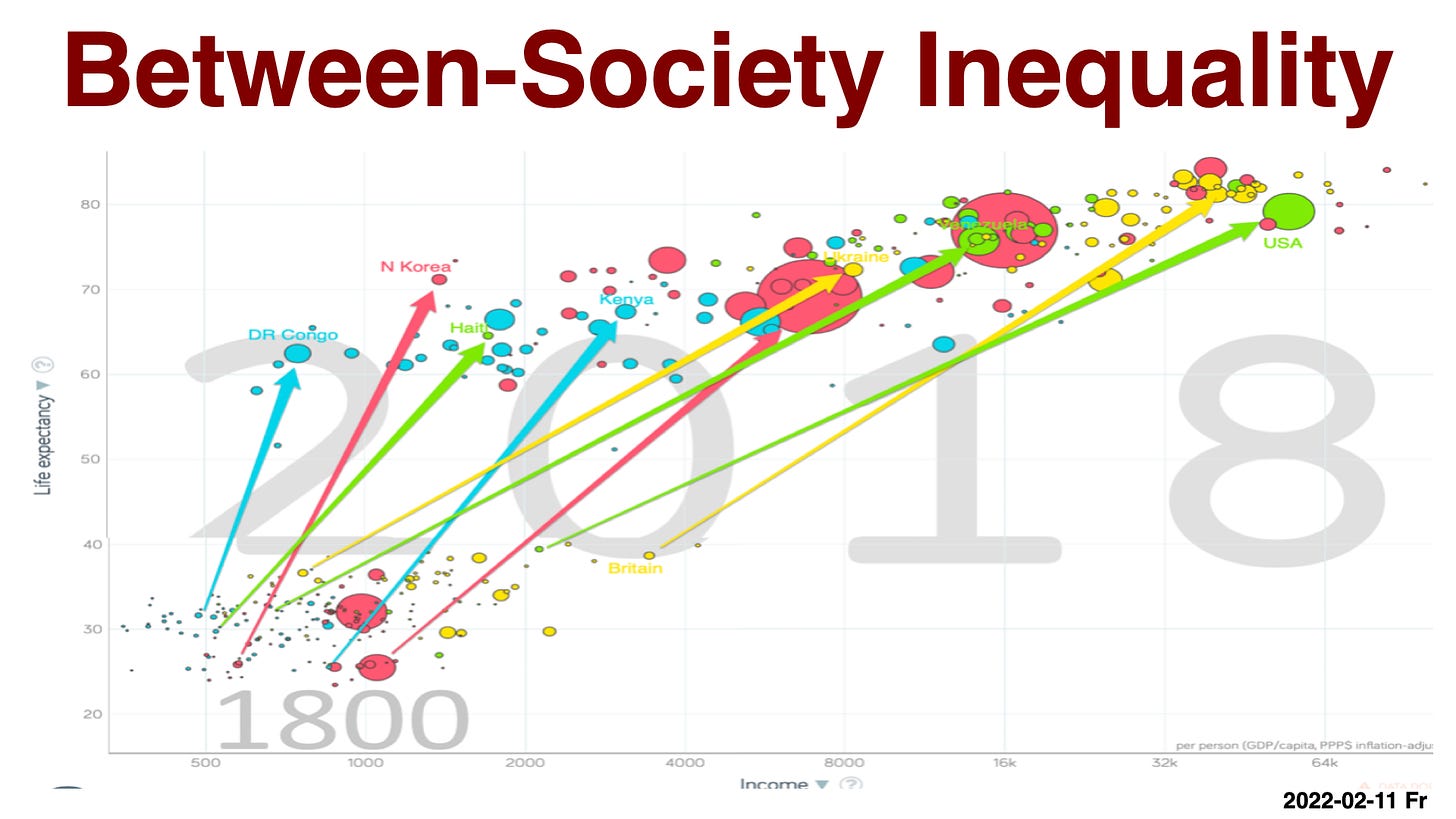

Fortunately for my task, other people I have before not only tried to count but have been brave and bold enough to put their attempts at counting out there in public. Here we have figures from the wonderful “Gapminder” project: <http://gapminder.org>.

Gapminder tells us that those of us in the United States today have an average real income of $64,000 of today’s purchasing power per capita.

This “international dollar“ is a rather strange measure: in it, commodities are valued not at the relative prices in US dollars in the United States today, but rather at statisticians’ guesses of the average or typical relative price structure in the world as a whole. It then benchmarks those values so that the value attributed to the United States is in fact the value of United States income per capita today using the United States’s relative price structure. The hope is that this measure removes artificial inflation of real income gaps across the world that would be generated by the fact that the commodities that poorer countries are relatively efficient at making happen to have artificially low prices in the United States, because the United States is so rich as to be nearly satiated with them.

I do think this procedure is the best that we can currently do. But that is debatable.

Gapminder tells us that India has an average annual real income level today of $6,800 international dollars per capita; had a level of $1,200 back in 1920, had a value of $1,000 back in 1870, six years before the proclamation of Victoria I Hanover as Kaiser-i-Hind; and had a level of $1,200—the same as in 1920—back in 1800, three years after a young Irish aristocrat from a financially-embarrassed family with no visible skills save a not quite professional-scale virtuosity on the violin, Arthur Wellesley, arrived in India and turned out to be a military genius.

Gapminder tells us that life expectancy at birth in India was some 25 years in 1800, and is 70 years today.

Gapminder tells us that in the United States average annual real income per capita is $64,000 per capita; it was $5,500 back in 1870, and $2,000 back in 1800.

Gapminder tells us that life expectancy at birth in the United States was some 40 years in 1800, and is 78 years today.

Gapminder tells us that, on this “real international dollar” measure, the U.S. is 9 times as rich as India today, was 5 times as rich back I 1870, and was twice as rich in 1800.

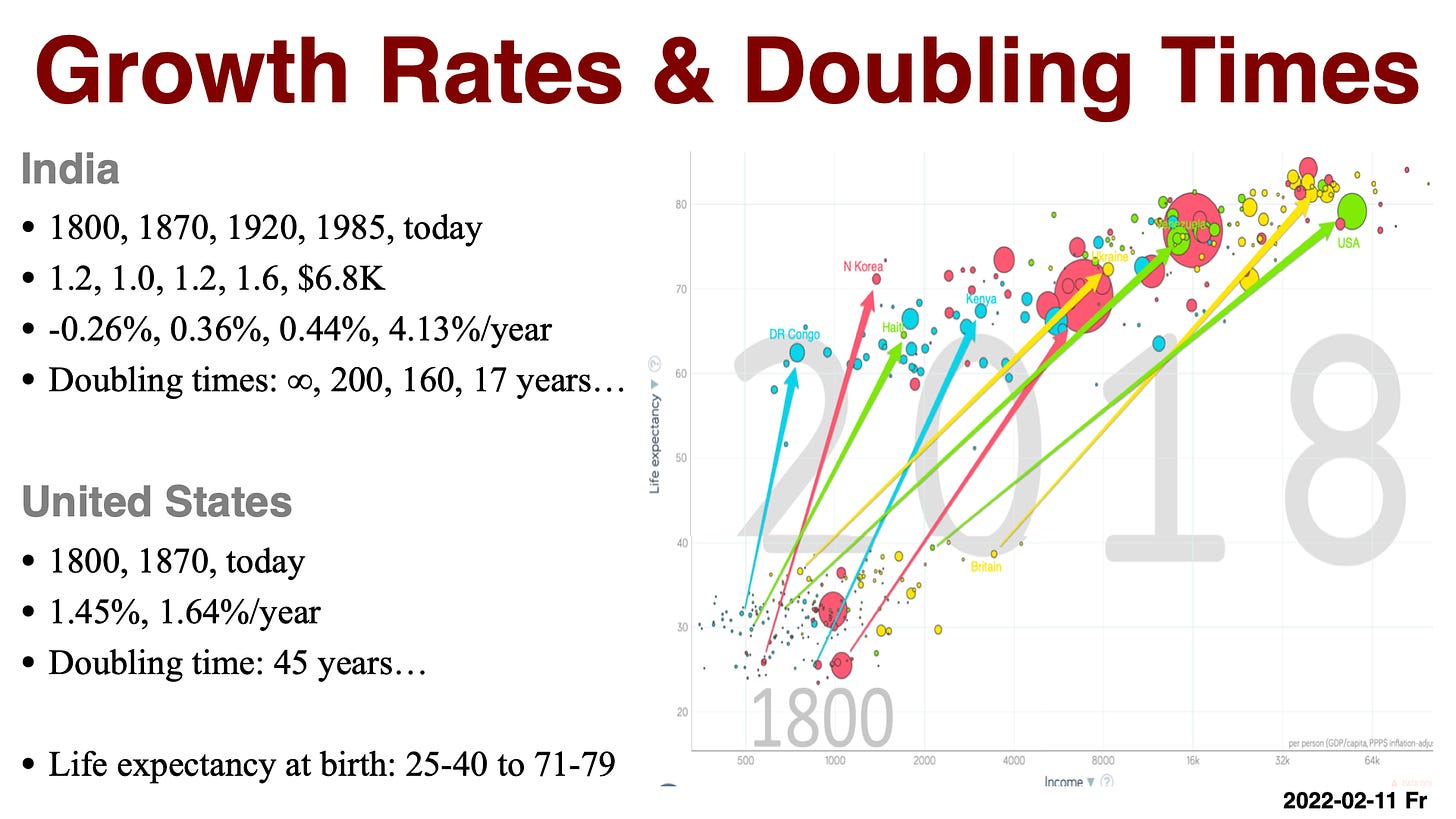

Gapminder tells us that from 1800 to 1920 there was no growth in average real incomes in India; that from 1920 to 1985 average real income grew at an average rate of 0.44%/year—a doubling time of 1600 years—and that since 1985 average real income has grown at 4.13% per year—a doubling time of 16 years. Gapminder tells us that since 1800 growth in average real incomes in the United States had been near 1.5%/year—a doubling time of 45 years—consistently since 1800.

3. A Wider View

We can take a wider view. We can step back to look at the world as a whole—looking at world averages, not just India’s and America’s average. We can step back to look at all human history since Deep Time, since the moment 75000 years ago when the several thousand of us who were the effective population size of the gene pool who are all of our genetic ancestors began to expand our population, and then begin the radiation that would carry their genes all over the globe, first in the horn of Africa, then to the rest of Africa, and across the Red Sea to Yemen and out to the world.

(Parenthetically, this is only the first of four radiations that I find particularly interesting these days: the second is the radiation of the grain-based societies of the agrarian age out of the Fertile Crescent of the Near East; the third is the radiation of the languages spoken 5000 years ago on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe by the domesticators of the horse and the inventors of the wagon—a radiation vast enough that languages descended from their Proto-Indo-European tongue are now spoken from Bengal and the Deccan west all the way around the world to Perth and Singapore, a linguistic radiation; and the fourth is what I hope will be a durable and complete but is now merely an ongoing global radiation of industrial technologies and supporting political and sociological ideals of reduced hierarchy, individual autonomy, and diffused social power.)

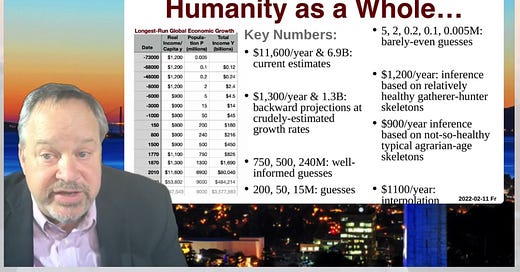

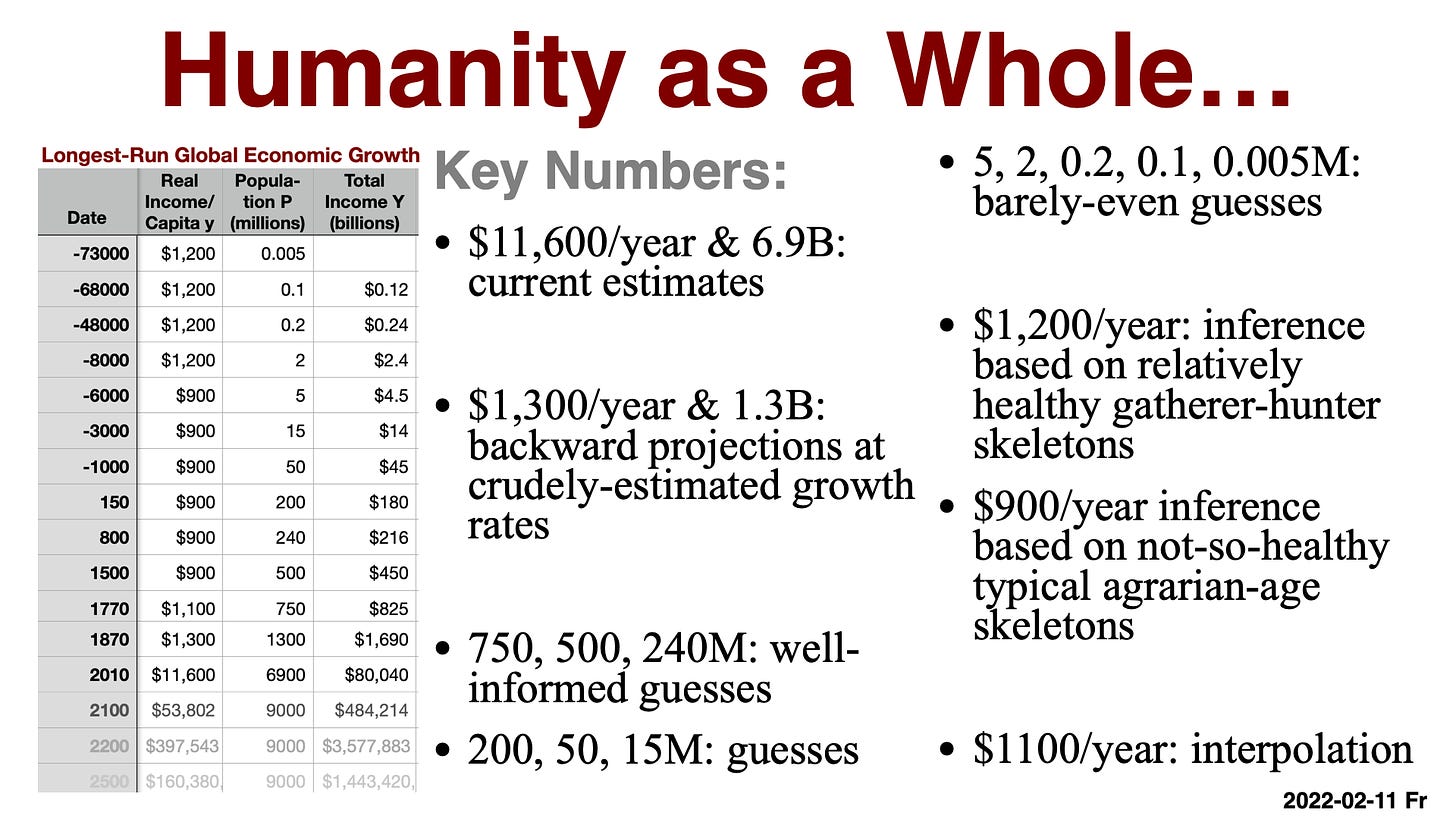

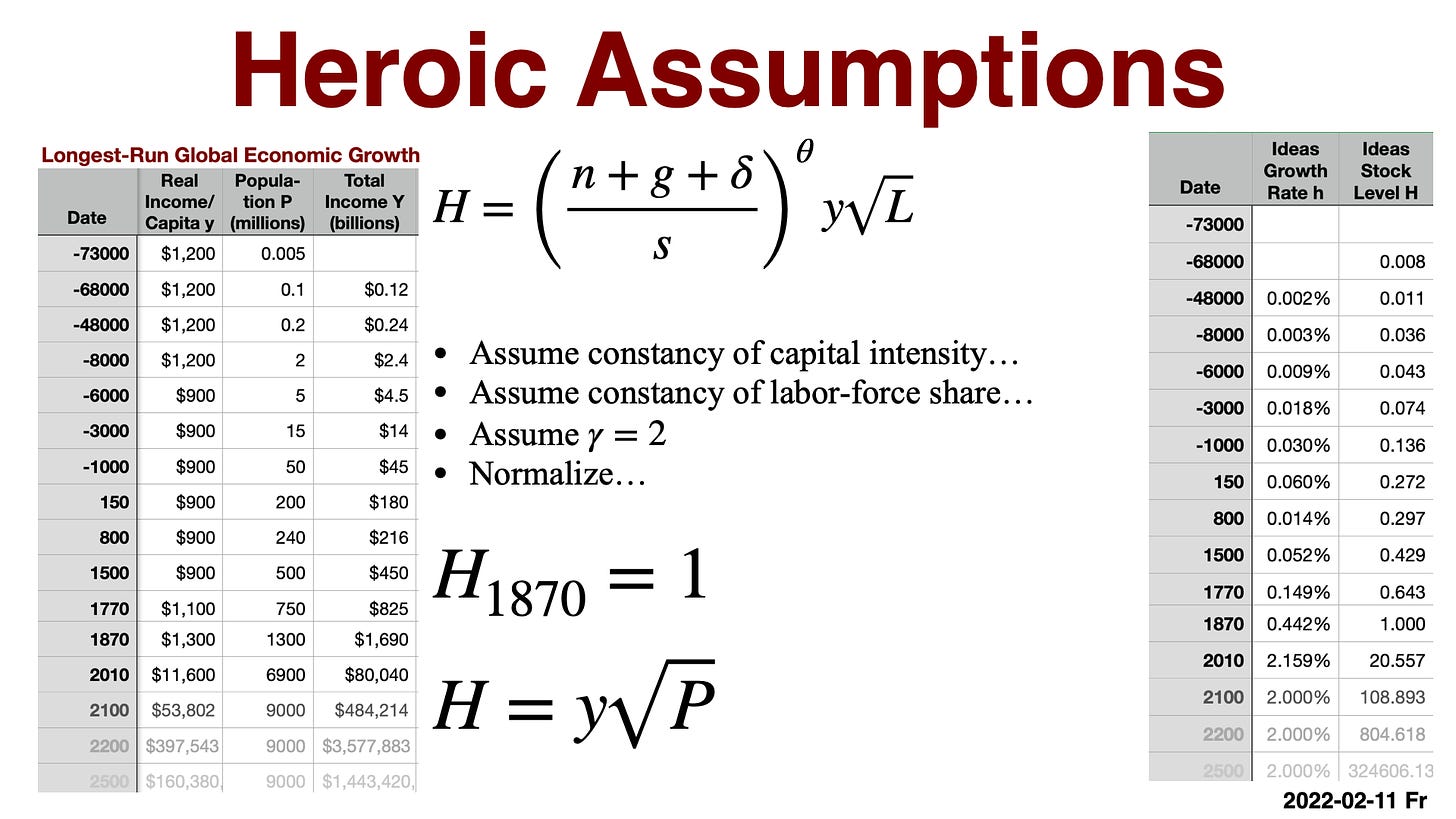

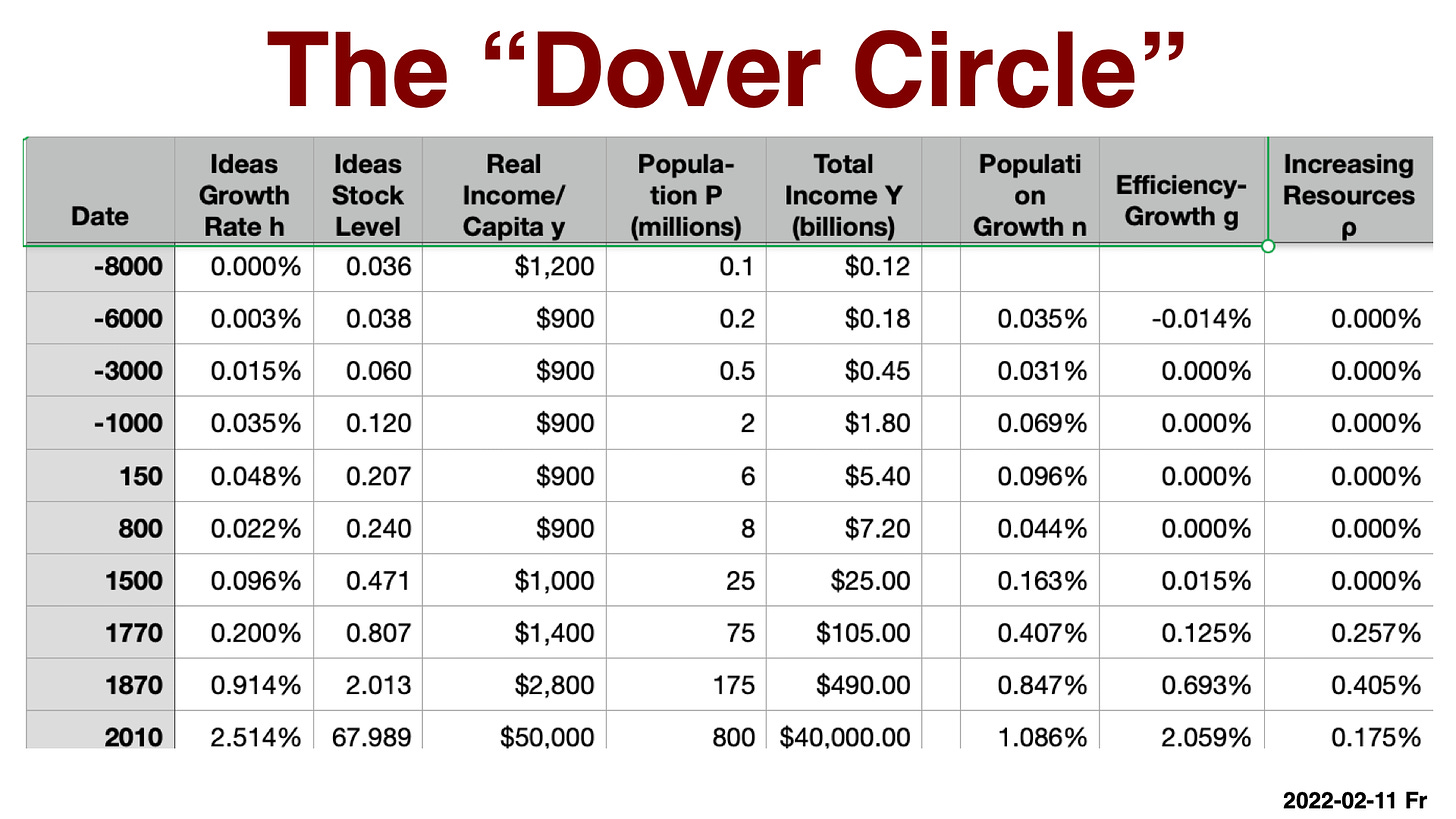

I have written down a table of numbers: average world real income per capita; estimated human population; total world real income. I have gone back 75000 years. And I have projected forward—assuming the world soon attains zero population growth and continues to deploy better productive technologies at the proportional rate it has since 1870—to 2100 and 2200.

For today, at least, we have numbers and estimates that technocratic bureaucracies have calculated, stand behind, and will at least semi-justify. Those are the “$11,600” average annual income and the “6900 million” estimated population as of 2010. Going forward to 2100, we have sensible demographic projections, and we can project technology and income to get a real projection: a population of nine billion forecast for 2100, and a world with an average annual real income level of $54,000—a world average as high as today’s global-north average. And then we can draw those lines out for another century, and imagine a world of 2200 with an average annual real income of $400,000 per capita. I see us as unlikely to reach that world, in which the average person is three times as rich as my family is, with me at my peak earning years, but it would be very nice to get there.

Going backwards from today, we have economic historians who have at least estimated what they regard as reasonable growth rates over 1870 to 2010. We can use these growth rates to project levels of world average real income for 1870. This introduces error: these growth rates are estimated with considerable errors; an error in the estimated growth rates compounds as we project back and induces an opposing-sign error in the estimate of the past level. And we have enough censuses to be confident of our 1.3 billion population estimate for the world as of 1870.

4. Estimates to Guesses

Back before 1870, I have written 750, 500, and 240 million for the world human population in 1770, 1500, and 800. These are demographers’ well-informed guesses. I have written 200, 50, and 15 million for the world human population in 150, -1000, and -3000. These are guesses. I have written 5, 2, .2, .2, and .005 million for the human population in -6000, and then ten, fifty, seventy, and seventy-five thousand years ago. These can barely even be called “guesses”.

For average income, I have written $1,200/year—$3.50 a day—as the average real income level ten thousand years and before, back in the gatherer-hunter age before the invention of agriculture. This is poverty, but not quite extreme poverty or dire poverty by the World Bank’s current measures. It is not that the typical person is so hungry most of the time that they have a hard time thinking of much else, and not so poor that the leisure time they take they do so only because there is nothing additional that they could do that they have the strength to carry out. This is a guess, but this is an informed guess: it is an inference based on relatively healthy gatherer-hunter skeletons that we have found and analyzed.

For average income, I have written $900/year—$2.50/day—as the average real income level from eight thousand years up to 500 years ago, back in the agrarian age. This is poverty, close to extreme poverty by the World Bank’s current measures. The typical average person is close to being so hungry most of the time that they have a hard time thinking of much else. The typical woman is close enough to being too skinny to ovulate regularly. The typical child is sufficiently malnourished to be stunted in their adult height by three inches or more—not the upper class: the upper class is as tall as we are, almost. The typical child is sufficiently malnourished to have a compromised immune system. It is a world in which for women the overwhelming—and for men the predominant—source of social power is to have living sons, one-third or so of families are unable to accomplish this: their sons all die before they establish families of their own. Thus while this $900/year is a guess, it is, I think, a well-informed guess: it is an inference based on the stunted typical agrarian-age skeletons, and on the failure of so many families which have enormous material and sociological incentives to raise living sons to have managed to do so.

And the $1100 number for average world income per capita in 1770? That is an interpolation, backed by the fact that population growth materially accelerated worldwide across the 1500 watershed boundary-crossing between agrarian and imperial-commercial age societies, strongly suggesting a diminishing of the punishment inflicted by material necessity on a humanity beginning to crawl out from beneath the harrow of Malthus.

5. Counting the Right Things

Bureaucratic counts—well-founded estimates and projections—informed guesses—guesses—barely even guesses. This table has problems. But there is, I think, a bigger problem: Is this table even measuring the right thing?

When we speak of human wealth, what we are thinking of is of its usefulness to us. We are thinking of its impact on our “utility“, to momentarily drop into the inadequate and false Benthamite philosophical-psychology that underpins and has always underpinned economics. We hold firmly to this inadequate and false philosophical-psychology. In fact, we run with it, in spite of our knowledge of its inadequacies and falseness. And these estimates—guesses—barely-even-guesses—do not fit with it.

These numbers are all estimates of the cost in terms of resources of producing commodities and the efficiency with which those resources are used to produce. There is, however, a huge wedge between use value to the human and exchange value to the market. We call that “user surplus”. Simon Kuznets in the 1930s laid down the principle that we would not try to estimate that. Why not? Because he needed a number for the aggregate size of the economy that he could calculate in his office in time for it to be of use to somebody. We still follow him, even though we could do better, and ought to know better.

But the gap between market exchange value and typical human use value is enormous, and often changing.

Here is a sharp example: Nathan Mayer Rothschild was the richest private citizen in the world in the first half of the 1800s. Nathan Mayer Rothschild was dead in his 50s of an infected abscess, in his butt. The use value to Nathan Mayer Rothschild of a single course of the antibiotics our biochemists and doctors have given us since the 1940s would have been very large to him: nearly the entirety of his wealth—he would have been willing to sacrifice it in order to see his grandchildren grow.

Does that mean that every single one of us who has access to antibiotics has a use-value of the commodities that we consume that makes us far richer than Nathan Meyer Rothschild?

In a profound sense yes.

But Nathan Meyer Rothschild’s wealth had other purposes than merely allowing him to survive disease. His wealth gave him the social power to command the attention and obedience of hundreds of thousands, should he wish to do so. For many rich people, that power to command attention-and-obedience is the principal source of satisfaction: “it’s no longer about what you can buy it’s about prestige, about receiving deference, about… ‘seeing ’em jump’,” as Paul Krugman once put it. And that social power to command attention-and-obedience is by definition and necessity zero sun. If you think that the important element of wealth is power to command, collectively we cannot truly grow “wealthier”. If you think that is powered to manipulate nature and cooperatively organize ourselves that is important, each of us today is richer and more powerful than the gods of the past. The god Odin—played by the actor Anthony Hopkins in the Marvel movies—one of his major powers was his ability to see and hear things far distant. He obtained this power by consulting soothsayers, and by having two tame ravens who could talk. They would fly around the world, or at least parts of Scandinavia, watching and listening, and they would return to whisper in his ear. All of us vastly outpower Odin in this dimension.

6. “What Is Best in Life?”

Which is important depends on who you are, what you want to do, and what you think is best in life:

Once Genghis Khan asked Boorchi Noyon, who was the chief of the generals, “what is the greatest joy and pleasure for a man?”

Boorchi said: “It is to go to the hunt, a spring day, mounted on a beautiful horse, holding his fist on a hawk or a falcon, and see it cut down its prey.” The prince made the same question to General Bourgoul, and then to other officers, who all answered as Boorchi.

“No,” said Ghengis Khan, “the greatest enjoyment of a man is to overcome his enemies, drive them before him, snatch what they have, to see the people to whom they are dear with their faces bathed in tears, to ride their horses, to squeeze in his arms their daughters and women…”

And these all bleed into each other.

A book has come down to us written by Aristotle around near -350, his Politics. The first scroll is about economics: the acquisition, preservation, and use of resources, written from the perspective of an upper-class Greek landlord-aristocrat-philosopher. Aristotle sees the science of oikos-nomos, of the rules of household resource management, of economics, of the science of acquisition, as having four branches. The fourth and least important is the knowledge of production processes, technologies, and market conditions. You need to know these things: they are “not unworthy of philosophy”. Since you cannot make everything you need for a good life within your household, you have to trade an exchange, which means you have to decide what your household will produce in surplus that you can offer in exchange. Proper knowledge of technologies, production processes, and market conditions is essential to keep from being cheated by your counter parties and to use your household resources well in this dimension. But too great attention to this would be “crude”, in “poor taste”, and would tend to make you one of those people who tries to pile up wealth without limit and forgets what it is for, forgets how to live philosophically.

Another branch is more important than technologies in the markets: it is how to command your wife harmoniously, forte she does not have your rational soul and her excellence lies in obedience. (Do note that here Aristotle is arguing against his teacher Plato and Plato’s teacher Socrates, who held the opposite view—the the souls and excellences of men and women were of the same kind.) Still more important is how to exercise your “royal” rule as you raise your children properly.

And the most important element of economics? How to boss your slaves, so that they work hard and effectively to create the wealth so that you have the freedom and leisure to pursue your appropriate role in the political society that is the Greek city-state.

This is, Aristotle says, how it is and how it always will be: good societies need slaves, and lots of them, to be bossed around by those who excel in the rational elements of the soul. This will always be true, he writes, expect in fantasies in which:

every instrument could accomplish its own work, obeying or anticipating the will of others, like the [robot] blacksmithing statues of Daidalos, or the three-wheeled catering serving-carts of Hephaistos, which, says the poet, “of their own accord entered the assembly of the gods”; the shuttle would weave and the plectrum touch the lyre without a hand to guide them…. It is manifest therefore, that… of people… some are… slaves by nature. And for these slavery as an institution, both expedient and just…

Well, we have the robot blacksmiths of the inventor Daidalos and, while I have not seen the three-wheeled catering serving-carts that Homer imagined the smith-god Hephaistos made, we could build them. We have the weaving machines and the music players: nearly every song we think of immediately accessible wherever we are, and robot factories that contain the looms, a human, and a dog with, as Berkeley Business School Dean Ann Harrison says: “the dog there to deter machine-thieves, and the human there to feed the dog”.

If it is the usefulness to us of our collective powers to manipulate nature and organize ourselves that matters more, the estimated jump from a $1300 to an $11000 average annual income level vastly understates by how much our wealth exceeds that of all past ages. If it is our net ability to “see them jump” that matters more, the estimated jump overstates how much our greater wealth matters.

7. Economic Theory

By now I have set out some numbers, counted some things, and warned you that my counts are unreliable, or of the wrong things, perhaps, or maybe that there is no right thing to count. But now let me stake out this table of numbers as a hill that I will die on, and draw out some implications.

First, let me set out a simple aggregate economic model: a production function with output per worker y equal to capital-intensity kappa raised to a parameter theta that measures the salience of capital relative to worker skills and efficiency in production, all multiplied by the efficiency of labor E; an equilibrium condition that an economy’s capital-intensity kappa will be the quotient of the economy’s savings-investment share of spending in total income s, divided by the economy’s investment requirements, which are the sum of the labor-force growth rate n, the labor-efficiency growth rate g, and the capital-depreciation rate delta; last, the efficiency of labor E is equal to the value H of the stock of useful ideas about technology—how to manipulate nature and organize humans—times natural resources R per worker L raised to one over delta, where delta is the salience of ideas relative to resources in generating worker efficiency.

This is an economic model. It is all of a useful filing system for analyzing growth, a powerful intuition pump for generating ideas about where in the economy we should direct our attention, and also a pointless and exclusionary formal ritual that makes some voices hard to hear.

I want to take this model seriously, and make three further assumptions: the first is that variations in capital intensity are unimportant and can be neglected, the second is that variations in the ratio of the labor force to the population are unimportant and can be neglected, and the third is that the value of the parameter gamma is 2. Under both of those assumptions, it is then the case that we can determine humanity’s technological prowess at any moment in history—its level of H—by simply taking our estimated (or guessed) level of output per capita and multiplying it by the square root of population. Normalize this H by then setting its value in 1870 at 1, and calculate H’s proportional growth rate looking back through history

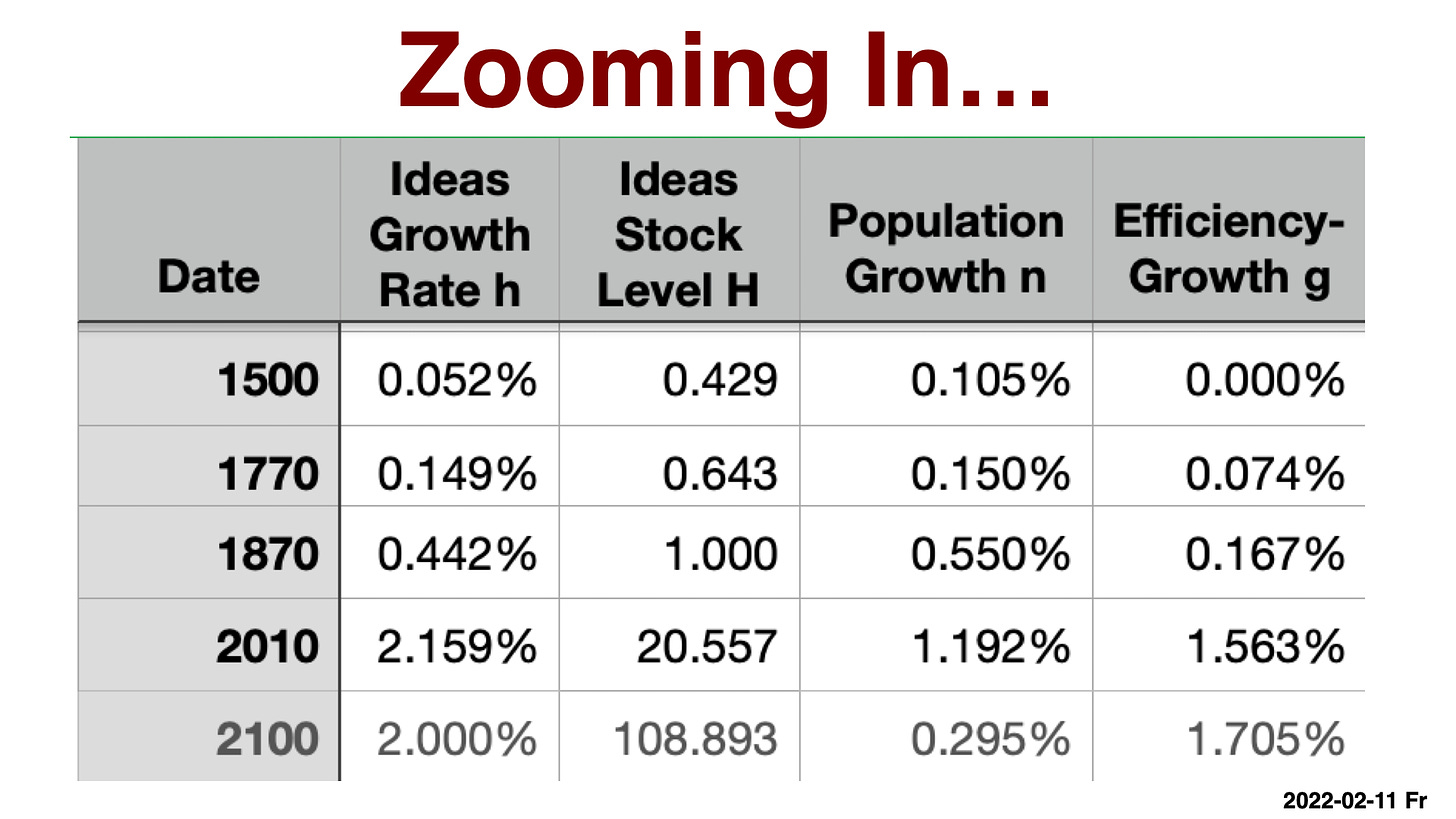

8. Since 1500

Now let us zoom in on the last five hundred and the next eighty years. What can we say about human technology and its past and future likely future pace of improvement?

The first thing we note is that, worldwide, the average rate h at which the deployed-and-diffused ideas stock H has been growing has been 2.1%/year since 1870. That was more than four times as fast as the rate of increase had been during the 1770-1870 century of the British Industrial Revolution during which European colonialists had conquered—or, in the case of Africa south of the Sahara, were about to conquer the world.

That was fourteen times the pace of growth of the technological-ideas stock deployed-and-diffused during the 1500 to 1770 imperial-commercial age that saw the Spanish-Portuguese conquest of America, the rise of the European seaborne empires with their joint monopoly over ocean trade and fortified ports, the West African-Caribbean slave trade, and the Columbian Exchange as the Old World got corn, the potato, chocolate, tobacco, and the rest of New World biotechnology; and the New World got the animal- and small grain-based agricultural biotechnology of the Old World—plus Bubonic Plague and smallpox.

And that was twenty-two times the pace of growth of the pre-1500 agrarian age.

We have seen and are still seeing and will almost surely see in your lifetimes this process continue: technological progress at a rate that before 1500 took a century, we see every five years. Managing that pace of extraordinarily rapid and net-productive creative destruction in the interest of creating a truly human world is something that our governments and societies are not conspicuously excellent at, or succeeding in.

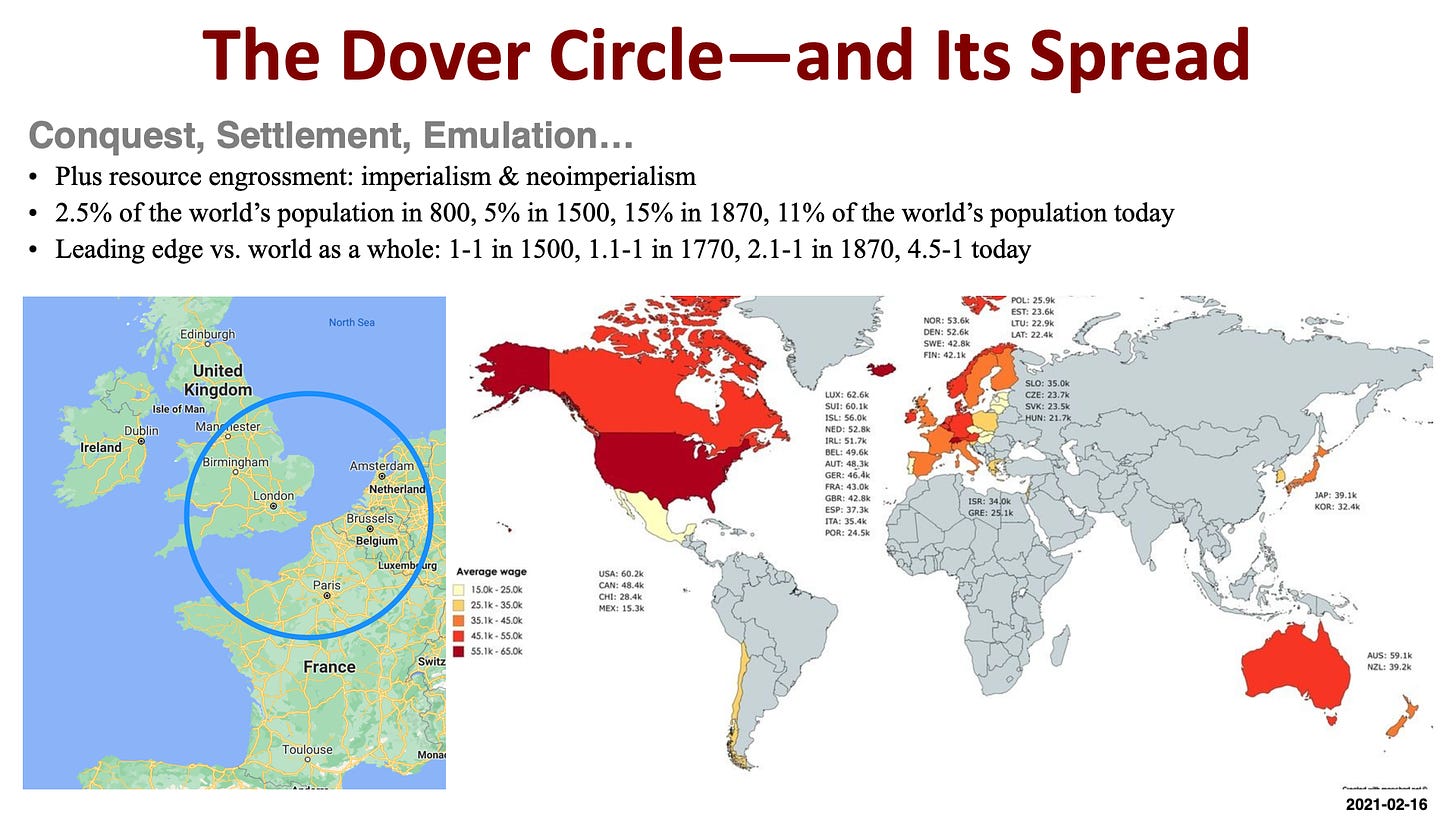

9. “Dover Circle” & Progeny

Most conspicuous today among the failures of global economic management is the extraordinary failure of the technologies that have been developed since 1770 to fully diffuse across the world. The industrial innovations had their initial start in the Dover Circle: 300 miles in radius, centered on the port of Dover in the southeastern corner of England.

Technologies and institutions were then carried and diffused via natural increase, conquest, settlement, emulation, osmosis, and diffusion thought the world. But only partially and incompletely. The result is that today there is a thing called the “global north”, which in its imagination at least traces continuity of descent and commonality of identity in some sense with the civilizations of the Dover Circle of half a millennium ago—a day when the Dover Circle was nothing special, and no prince or merchant of the Yellow, Yangtze, Mekong, Ganges, Indus, Syr Amu, Syr Daria, Tigris, Euphrates, or Nile valleys would have wanted to change places with their counterparts of the Rhine, Meuse, Seine, or Thames.

The result is that there is today a thing called the “global south”, which is the rest of the world, which stood, on average, at least at par with the people of the Dover Circle in income and technology 500 years ago, who today have average incomes less than 20% as high.

This between-society inequality may or may not now be in a process of long-term erosion. But it certainly was in a process of tremendous expansion—divergence—from 1800 to at least 1980. The current 4.5-1 edge of the global north relative to the world average is principally due to the differential creation and adoption of technologies, and secondarily but substantially due to the engrossment of the world’s natural resources: conquest, occupation, extortion, and purchase.

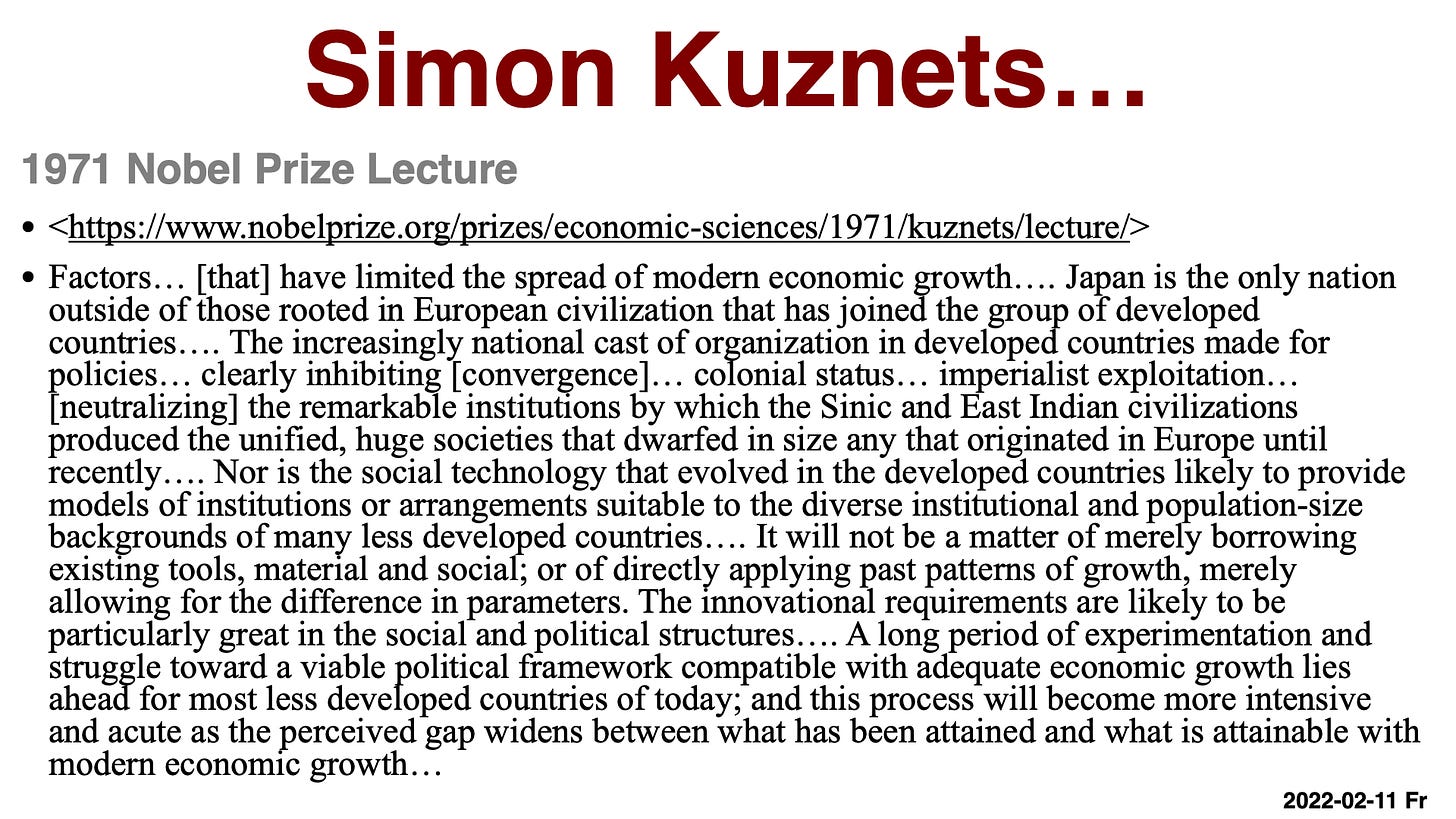

Simon Kuznets in his Nobel Prize lecture back in 1971 pointed to:

Factors… [that] have limited the spread of modern economic growth…. Japan is the only nation outside of those rooted in European civilization that has joined the group of developed countries…. The increasingly national cast of organization in developed countries made for policies… clearly inhibiting [convergence]… colonial status… imperialist exploitation… [neutralizing] the remarkable institutions by which the Sinic and East Indian civilizations produced the unified, huge societies that dwarfed in size any that originated in Europe until recently…. Nor is the social technology that evolved in the developed countries likely to provide models of institutions or arrangements suitable to the diverse institutional and population-size backgrounds of many less developed countries…. It will not be a matter of merely borrowing existing tools, material and social; or of directly applying past patterns of growth, merely allowing for the difference in parameters. The innovational requirements are likely to be particularly great in the social and political structures…. A long period of experimentation and struggle toward a viable political framework compatible with adequate economic growth lies ahead for most less developed countries of today; and this process will become more intensive and acute as the perceived gap widens between what has been attained and what is attainable with modern economic growth…

Nothing in the history of the past half-century—especially not the institutional dysfunctions we clearly see in much of the global north—suggests that these worries by Simon were overstated.

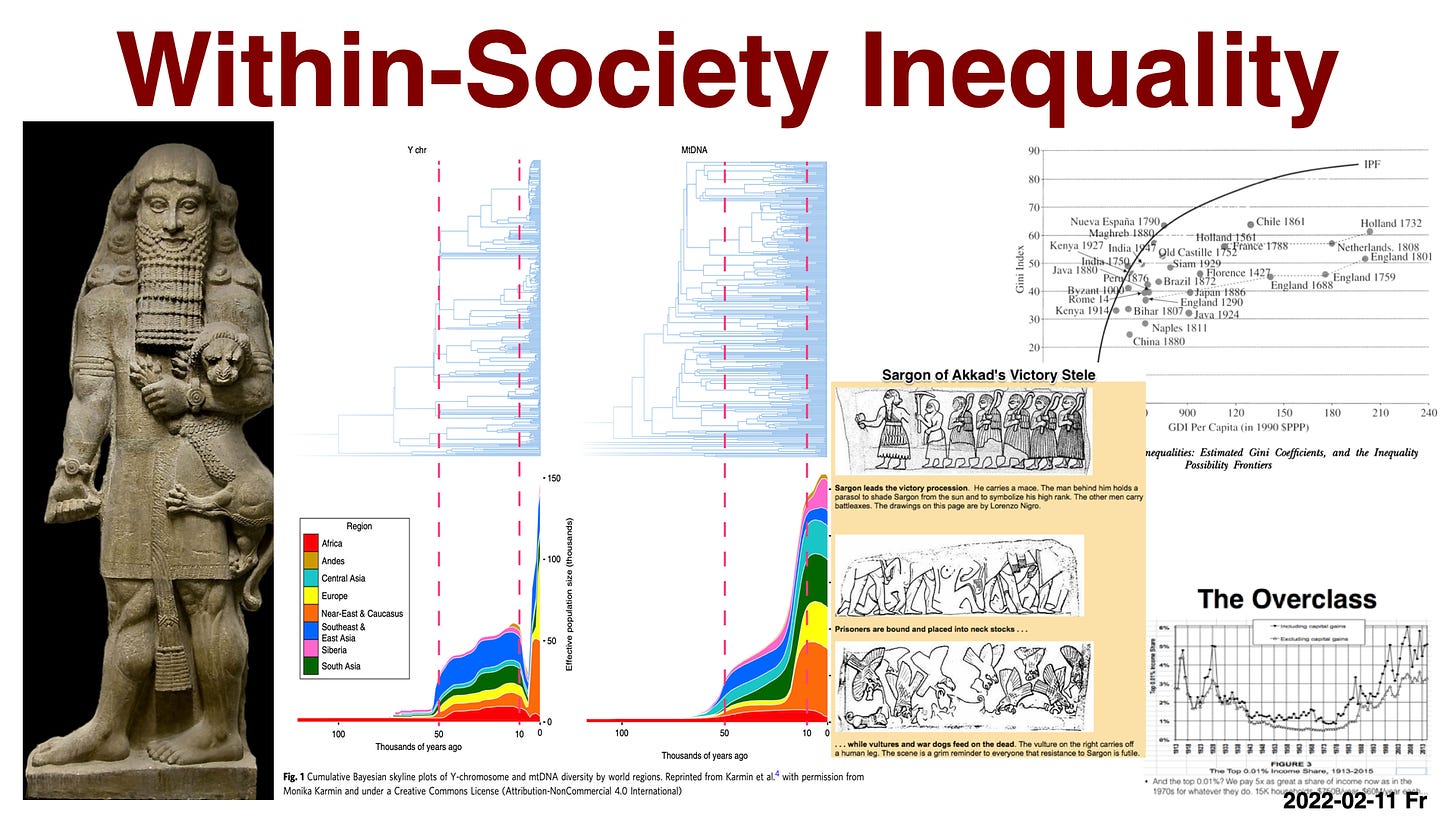

10. Within Societies

I do not have time to do more than observe that any assessment of societal wealth must deal not just with averages but with within-society distributions as well. This is particularly true in a market economy. In a non-market or in a partial market economy there are many sources of social power in many ways to access resources other than through the control and expenditure of wealth. People then have rights, springing from their membership in a status group, in a kin network, or in some other sociological institution. But in market society the only rights that are recognized, the only sources of social power, are property rights. And an a market society the only property rights that are worth anything are those that aid in the production of commodities for which the rich have a substantial market demand.

As Amartya Sen (who I think still has my copy of Karl Polanyi’s Trade and Market in the Early Empires that he borrowed around 1990) has stressed, an unequal market society will be one in which the market—and so society—literally does not care whether those without wealth live or die. It is a matter of indifference to it, because the only thing it cares about are effective demands, and those without wealth have no effective demand for anything.

I do not have time and space to do more than gesture at within-society inequality: by gender, by ethnicity, by class, by status group, by kinship. But any assessment of a society’s wealth, or perhaps of a society’s ability to make proper use of its potential wealth, must assess not just averages but the within-society inequality dimension as well.

11. Conclusion

Today has seen me undertake a towering construction, but one truly based on a foundation of straw. That is why I warned you back at the beginning that I saw my role as one of provoking and starting a discussion, rather than providing solid and truly scientific or stable conclusions.

Nevertheless: to answer the question of how much more wealthy are we than our predecessors, the answer is 20. We humans today are 20 times as potentially wealthy as our predecessors back in 1870. And our predecessors back in 1870 were themselves some 20 times as wealthy as our joint predecessors back in the early agrarian age, 7000 or so years ago. From the early agrarian age to 1870, however, increased human potential wealth was used overwhelmingly to support a larger human population and secondarily to enrich a larger largely parasitic—if at times civilizationally glorious—upper class, rather than for the betterment of the average or the typical human. Since 1870, with the coming of the demographic transition, we have done much better. Nearly any previous society would say that we are certainly wealthy enough in per capita terms that it is very surprising that we have not used our wealth to create a real utopia, a truly human world.

Yet it is manifestly the case that we have not.

However: I see you very strong arguments that the factor of 20 by which I claim potential human wealth exceeds that of 1870 is a vast underestimate. The factor of 20 is really an estimate of commodity value based on factor cost. An estimate based on the use value, on the material basis for human flourishing, would see our relative wealth as vastly greater.

And yet: An estimate based on the usage we have made of our potential wealth might well be significantly smaller. For one thing, of the four freedoms that Franklin Roosevelt thought ought to be every person’s birthright—freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear—only freedom from want can be directly secured by material wealth. You a wealthy society should make the benefits of impinging on the freedoms of others vastly less and the difficulty of vindicating those other freedoms vastly less as well. And you would be right. Nevertheless, we as a species have not vindicated and secured those other freedoms.

But before 1500, people located utopias either in the heavens, or in some past golden age, or at the very least elsewhere on some distant island. The way things were in this world, in this fallen sublunary sphere at least, was that of the Wheel of Fortune. In Aristotle‘s framing, a monarchy turns into a tyranny switch is overthrown by an aristocracy which turns into an oligarchy which is overthrown by a democracy which turn into an anarchy which is then succeeded by a monarchy again, in a cyclical process with a good and a down phase in every third of the wheel’s revolution. But short of God or the gods coming down to earth, bringing a New Jerusalem, or at least the three-wheeled robot catering serving carts the smith-god Hephaistos is making when Akhilleus’ mother the demigoddess Thetis arrives to divert him from making the artifacts of peace to the weapons of war for her son, human history and wealth does not have a direction.

Starting in 1600, a direction begins to appear. Tommaso Campanella, in his The City of the Sun, writes about how there has been more historical progress in the past century then an all previous epochs (even though he attributes this progress to the astrological influences of the planet Mercury and the constellation Scorpio). Francis Bacon writes in his The New Atlantis that human society has been transformed utterly by the triple inventions of the compass, gunpowder, and printing. And he calls for large-scale government-sponsored research and development to produce more new inventions, to the “enlarging of the human empire” and the “effecting of all things possible”.

I think that both of their reactions to the sight of our civilization today would be puzzlement and confusion. Why, given our technology-driven wealth, is the world today is not much more of a utopia then it actually is? Why have we not done better with our technological wealth and power than we have?

I have a book about this, focusing on 1870 to 2010. It is called Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of huge 20Th Century. It is forthcoming from Basic Books on September 6 <https://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>.

Thank you very much for inviting me, and for listening to me today.

<https://watch.mmhmm.app/z_ps77rbgCwbH8UexkzsDX>

<https://www.icloud.com/pages/0eeC0pIaHM6W71ZfQtUsQQfzw> <https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/---st-stephens-2022-02-11.pdf> <https://www.icloud.com/keynote/018P8NckvObBEa0e2ncoz3tOw> <https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/st-stephens-2022-02-11:12.pptx>

5697 words

I don’t think you even have to resurrect Bacon to get a take on the letdown of our technologically advanced modern world. Many of us are supremely disappointed that the best we have done since walking on the moon is a battery operated car, auto-tuned pop divas, and an app that makes your face morph into funny hieroglyphs that disappear soon after posting. Sigh.

You should fudge the numbers to make the answer 42.