DRAFT: I Get to Talk About the 2nd Industrial Revolution in American Economic History on Monday!

Behind the paywall because I am not yet fully happy with it. Lecture: Innovation, Immigration, & Industry: The 2nd Industrial-Revolution Era Making of the American-Century Economy…

Behind the paywall because I am not yet fully happy with it. Lecture: Innovation, Immigration, & Industry: The 2nd Industrial-Revolution Era Making of the American-Century Economy…

The lecture needs a much stronger narrative thread…

The one I am going to choose—and have to incorporate into my notes—is this:

The United States as of 1880 had developed institutions—an immigrant absorption and assimilation system, a mass-education system, an engineering system, an industrial research system, and a managerial-corporation system—that were separate from but meshed extremely well with the market economy.

These institutions were the knock-on extended long-run consequences of the adoption of the Hamiltonian Program by the Jeffersonian ruling élite of the Federalist Era.

The United Kingdom as of 1880 had not: it was left with simply the market economy.

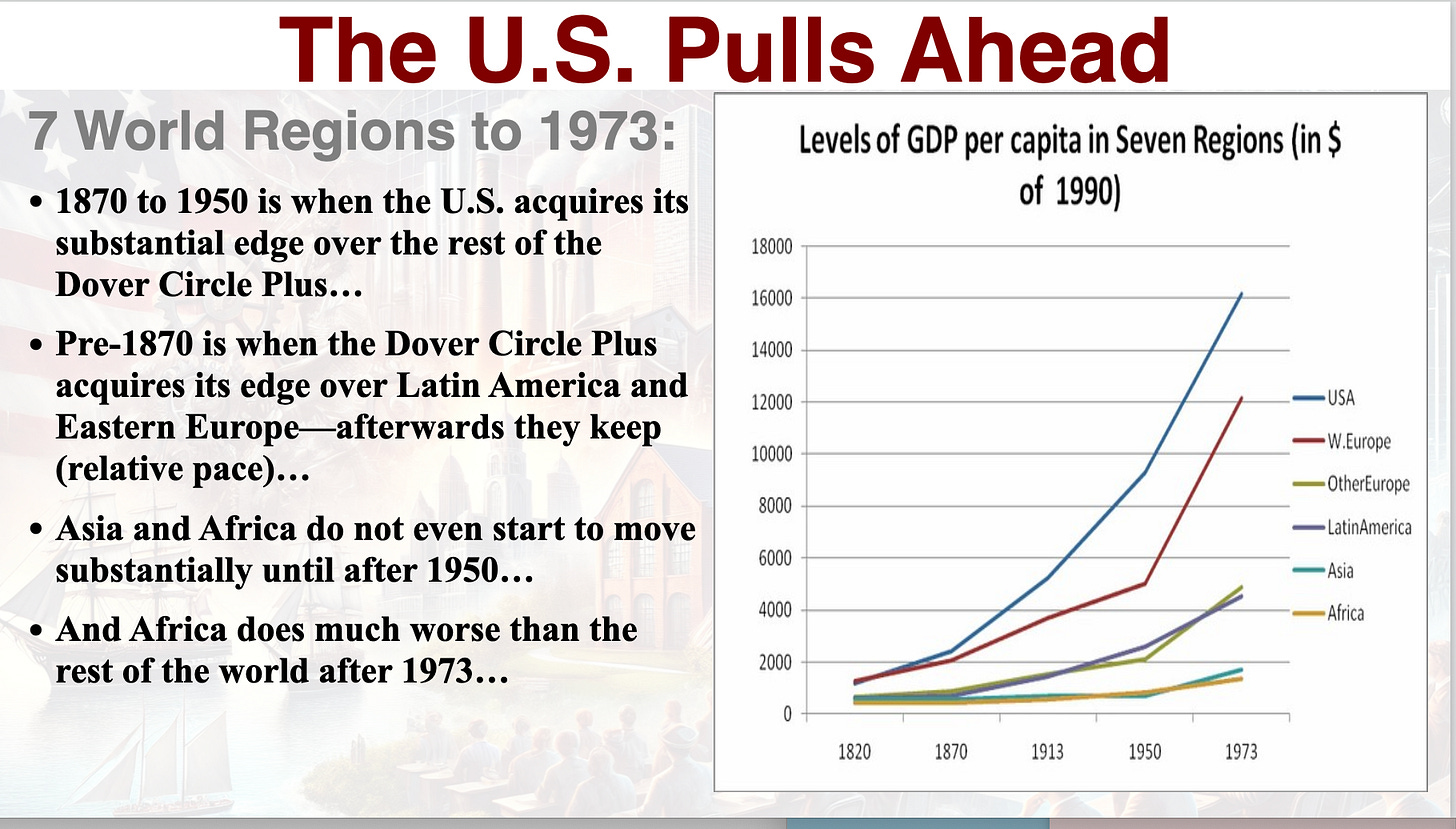

The post-1880 difference in economic growth performance was absolutely stunning. In the UK the wave of growth starts to ebb as steam and machinery approach their upper logistic asymptote. In the U.S. Kuznetsian Modern Economic Growth arrives.

The Coming of the American Century

1880 to 1930 is when the United States goes from 50 million (compared to 35 million for the United Kingdom) to 120 million (compared to 45 million for the UK) in population, and from roughly $4500 (compared to $5500 for the UK) to $8600 (compared to $7100 for the UK) in GDP per capita. If in 1880 you subtract off the sub-citizen population of the United States you rare left with 43 million. If you add in the settler populations of the British Dominions you get the same 43 million. Taking account of industry, production, trade, and population (either full-citizen or total), the British Empire had significantly more heft in 1880 than the United States had. By 1930 that was no longer true?

The reasons? America grasped the opportunity to develop and deploy the technologies of the 2nd Industrial Revolution. The British Empire did not. And the United States welcomed and assimilated the wave of immigrants coming out of peripheral Europe (but not the wave from China). The British Empire did not.

The Second Industrial Revolution & the Rise of the Modern Economy

We are now at a crucial turning point in this course on the history of the American economy. We are now halfway through, at the crux.

The Second Industrial Revolution, which unfolded between 1870 and 1914, was a period of rapid technological, industrial, and economic transformation. While the First Industrial Revolution (roughly 1760-1830) was driven by steam power, textile manufacturing, and iron production, the Second Industrial Revolution introduced electricity, internal combustion engines, chemicals, steel, and mass production techniques. This period saw the rise of large corporations, industrial research laboratories, and managerial capitalism, laying the foundation for the modern economic system.

The 2nd Industrial Revolution introduced innovations that reshaped nearly every aspect of industry, transportation, and communication. It saw the rise of electricity, steel, petroleum, and chemicals, as well as new corporate structures and financial systems that allowed firms to operate on an unprecedented scale. This period was marked by the emergence of mass production, the professionalization of management, and the development of industrial research laboratories, all of which laid the groundwork for the United States’s astonishing economic growth and relative heft in the 1900s.

The 2nd Industrial Revolution was indeed the transformative event that turned the entire 1900s into the American Century, and America into, as Leon Trotsky put it, the furnace where the future was forged,

The Pioneering Role of Railroads:

One of the most significant catalysts of the Second Industrial Revolution was the expansion of the railroad network. Railroads revolutionized American business by linking distant regions, enabling mass distribution, and creating national markets. They allowed raw materials such as coal, iron, and lumber to be transported efficiently, fueling the growth of heavy industries.

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 was a milestone that unified the country economically, reducing travel time from coast to coast from several months to mere days.

Railroads also pioneered modern corporate management structures. Due to the complexity of operating vast railroad networks, companies developed hierarchical management systems with salaried executives and specialized departments for finance, logistics, and engineering (Chandler 1992). These innovations in corporate organization soon spread to other industries, laying the foundation for the modern American corporation.

The Second Industrial Revolution & the Development of Underdevelopment

One of the most striking aspects of both Industrial Revolutions was the geographic concentration of economic and technological progress. From 1700 to 1975, almost all major advancements in manufacturing, engineering, and science were concentrated in Northwestern Europe and North America—what we might call the "Dover Circle" (the region surrounding Dover, England, symbolizing the industrialized European core). Outside this circle, countries often failed to develop significant manufacturing industries, despite technological progress being diffused globally.

This had profound consequences. Many nations, such as Nigeria, became dependent on primary commodity exports (e.g., oil, minerals, or agricultural products) rather than developing high-productivity industrial sectors. Since primary commodities often have inelastic demand, most of the gains from technological improvements benefited consumers—who were primarily in wealthier countries—rather than producers in poorer regions. This dynamic contributed to the widening global economic inequality that persisted until the late 20th century.

Some exceptions managed to break free from the pattern of underdevelopment. These included:

Germany after 1870, which leveraged its state support for industrialization, its coal and iron resources, and a strong educational system to become a major industrial power.

Japan after the Meiji Restoration (1868), which rapidly adopted Western technologies and built a modern industrial economy.

South Korea after 1960, which followed a path of **export-led industrialization and state-directed economic policies**.

Most of all—the thing that makes it the “Dover Circle Plus” or the “North Atlantic Economy: rather than the “Dover Circle”—the United States (plus the province of Ontario in Canada, which formed an integrated industrial region with the American midwest), benefiting from Hamiltonian economic policies and a vast internal market.

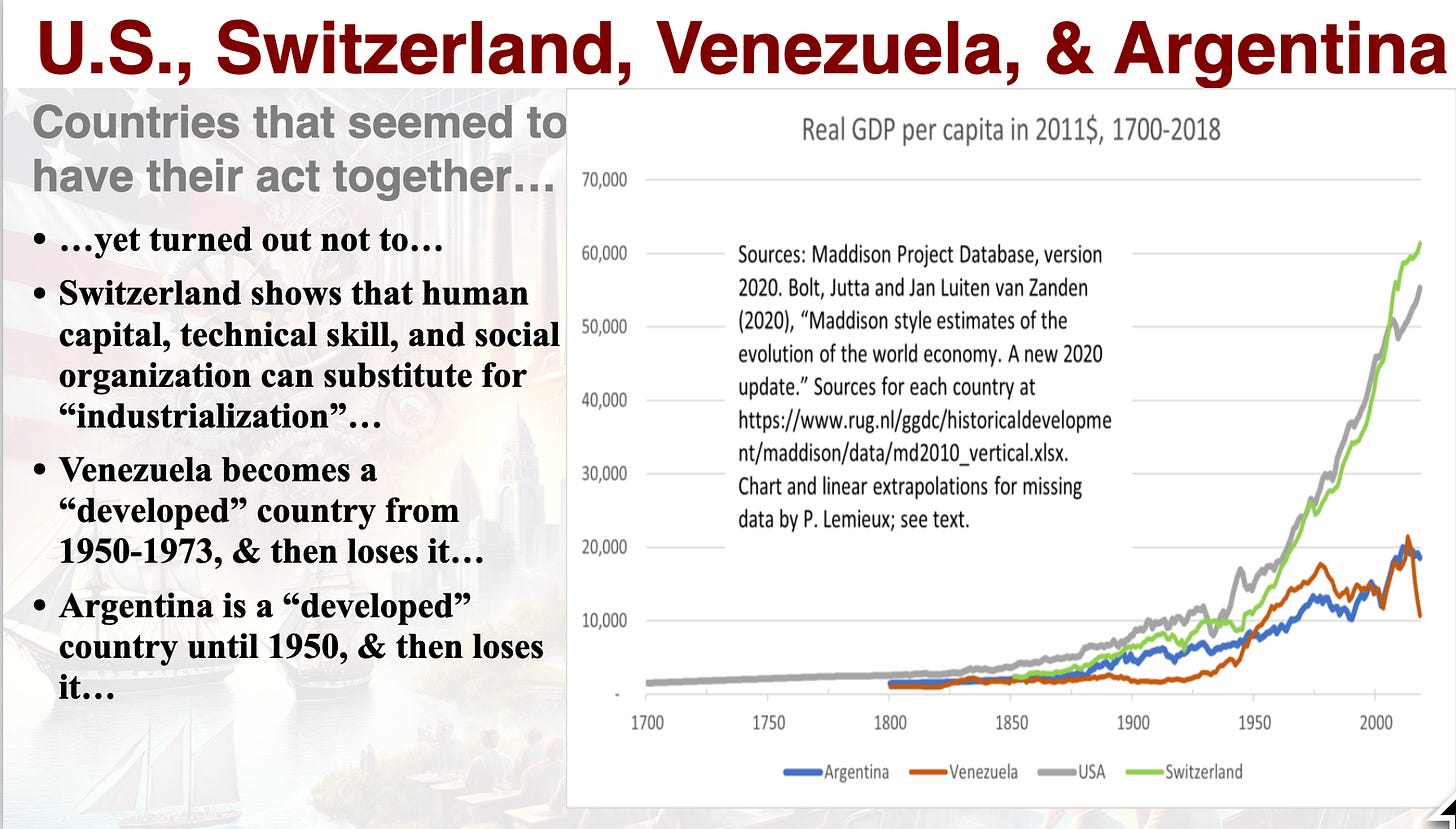

In contrast, resource-rich but sparsely populated countries like Australia, New Zealand, Chile, and Argentina became wealthy due to their high resource-to-labor ratios, but they still did not match the industrial cores of Europe and North America.

How Did the United States Do It?

Investment banks played a critical role in financing this expansion. Unlike Britain, which industrialized largely without investment banks, the U.S. (and continental European countries) relied heavily on financial institutions like J.P. Morgan & Co. and Crédit Mobilier to fund infrastructure projects.

The 2nd Industrial Revolution saw rapid advancements in steel production, machine tools, and chemical engineering. The Bessemer process, introduced in the 1850s, made it possible to produce high-quality steel at a fraction of the previous cost, leading to an explosion in infrastructure projects. Steel became the backbone of railroads, skyscrapers, and bridges, enabling urbanization on an unprecedented scale.

The machine-tool industry was another critical driver of economic expansion. Precision engineering allowed for the mass production of standardized parts, which reduced costs and improved efficiency. The growth of the professional engineering community and industrial research laboratories fueled further technological breakthroughs.

Industrial research labs, pioneered by firms like General Electric, Westinghouse, and DuPont, became the engines of innovation (Chandler 1992). These labs systematized the process of discovery and development, making research and development (R&D) an integral part of corporate strategy. In Germany, companies like BASF and Bayer led the way in chemical research, and their model was soon adopted in the United States. The routinization and rationalization of invention—the idea that scientific research could be managed and scaled like any other business process—was one of the key differences between the Second Industrial Revolution and earlier phases of economic development.

By the late 19th century, industrialists like John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, and Gustavus Swift had built vast business empires by taking advantage of the opportunities opened by the possibilities of vertical integration and economies of scale.

Rockefeller’s Standard Oil controlled every stage of oil production—from drilling and refining to transportation and retail—giving it an unparalleled competitive advantage.

Carnegie Steel utilized vertical integration to dominate steel production, owning mines, railroads, and factories to cut costs and control quality.

Swift & Company revolutionized the meatpacking industry by integrating slaughterhouses, refrigerated railcars, and distribution centers into a single supply chain.

These corporations were far larger and more complex than anything seen in earlier industrial economies. The rise of managerial capitalism, where salaried executives ran businesses rather than individual entrepreneurs, marked a shift in how economic power was organized (Chandler 1992). They:

created vast production networks that efficiently coordinated labor, materials, and technology.

integrated industrial research labs into their operations that systematically developed new technologies (e.g., General Electric, DuPont, Bell Labs).

used mass production techniques to lower costs and expand markets.

The U.S. maintained a competitive market economy, ensuring constant pressure for efficiency and innovation. As seen with Boeing and Intel today, even leading corporations must adapt or risk decline as long sas they face even some competition. Boeing, once an aerospace leader, now struggles with financial and production problems. Intel, once the dominant chip manufacturer, faces challenges from TSMC and Samsung, forcing it to reconsider its future. And in both cases the falls from grace took less than a decade.

Knock-on Effects of the Hamiltonian Program

By the late 19th century, the United States had thus emerged as the dominant force of the Second Industrial Revolution. This was not an accident. The Hamiltonian system, designed by Alexander Hamilton in the late 18th century, played a crucial role. Hamilton's economic vision included:

Government support for infrastructure** (canals, railroads, telegraphs).

Encouragement of manufacturing and industrialization as a national priority.

Protective tariffs to shield American industries for which a community of engineering practice might be nurtured.

Although Thomas Jefferson and his followers opposed Hamilton's ideas, they found themselves adopting his policies. The economic and more so the political logic behind them was inescapable, as even Jefferson himself found when he was in power. Thus by the time the Second Industrial Revolution took off, the United States was perfectly positioned to capitalize on new technologies. It had:

Avast internal market that supported large-scale production.

Rich natural resources (coal, oil, iron).

A welcome and welcomedcontinuous influx of immigrants, who provided labor and expanded demand.

A culture of innovation and engineering excellence, driven by its research institutions.

As historian Robert C. Allen notes, the U.S. economy developed rapidly because of four key factors:

America's labor force was not trapped in Dickensian conditions. Unlike Britain, where child labor was common, the U.S. prioritized education, ensuring a skilled workforce.

The U.S. had abundant natural resources, including vast coal and oil reserves.

America's capital stock expanded at an extraordinary rate, far exceeding Britain's. Investment in **factories, railroads, and infrastructure** provided an enormous market for technological innovation.

The U.S. encouraged social learning among engineers, enabling the rapid diffusion of new industrial techniques.

While Britain's technological growth slowed after 1880 as the wave of the First Industrial Revolution ebbed, the United States accelerated. By 1930, the U.S. had far overtaken Britain as the world's dominant industrial power. This dominance shaped the 20th century. Thus:

The U.S. became the "furnace where the future was forged", setting technological and industrial standards.

As American corporations pioneered new managerial and industrial structures, influencing businesses worldwide.

Consequences

However, this corporate dominance also led to growing concerns about monopolies. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was the first attempt to regulate big business, though it was initially used more against labor unions than corporations. It wasn’t until Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency (1901–1909) that serious trust-busting efforts began, targeting monopolies like Standard Oil and J.P. Morgan’s railroad empire (Boyer 2012).

While industrialists amassed vast fortunes, workers faced harsh conditions. Factory jobs often required long hours, low wages, and dangerous working environments. In 1890 alone, over 2,400 railroad workers died on the job, highlighting the risks of industrial labor. Think of it: work 40 years in the railroad sector, and at 1890 accident rates the odds were one in ten that your job would kill you. The result was

Indeed, corporations have always had dark sides. Consider Purdue Pharma, which notably prioritized profits over ethics—the opioid crisis, where Purdue deliberately promoted OxyContin addiction to maximize sales. Similarly, corporations often exploited workers, leading to violent labor conflicts. such as:

The Homestead Strike (1892), where steelworkers fought against wage cuts.

The Pullman Strike (1894), where railroad workers clashed with federal troops.

Thus the late 19th century also saw the interrupted rise and then defeat of labor unions and worker movements, including:

The Knights of Labor (1869), which advocated for an eight-hour workday.

The American Federation of Labor (1886), which focused on skilled workers and collective bargaining.

Major strikes, such as the Great Railroad Strike (1877), the Haymarket Riot (1886), the Homestead Strike (1892), and the Pullman Strike (1894), which saw violent clashes between workers and corporate-backed militias and ended with worker defeat.

The 2nd Industrial Revolution industrialization also coincided with mass immigration, particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe. These immigrants provided cheap labor but often faced discrimination and lived in overcrowded urban slums. The sheer scale of industrial production created new social divisions, with wealthy industrialists living in lavish mansions while factory workers struggled in tenement housing.

And America overtook and surpassed Britain in an astonishingly rapid relative global economic shift. A large number of factors contributed to this shift:

Scale and Resources – The U.S. had vast natural resources, including coal, oil, and iron ore, giving it an economic advantage.

Technological Leadership – The systematic approach to industrial research and development gave American firms a competitive edge.

Government Support – Tariffs, infrastructure investments, and pro-business policies fostered industrial expansion.

Mass Consumer Markets – The rise of department stores, mail-order catalogs (Sears, Montgomery Ward), and national advertising campaigns helped build a large domestic market.

By 1913, the developed regions of continental Europe—Germany, France, and Belgium—collectively significantly outproduced Britain in manufacturing. But it was the United States that had emerged as by far the dominant industrial force.

Conclusion: Market Economies Need Supportive Institutions

The Second Industrial Revolution teaches us that **market economies alone are not enough to drive sustained industrialization**. To succeed, economies need:

Supportive government policies, like the Hamiltonian system.

Strong educational and research institutions to foster technological progress.

Effective corporate structures, capable of large-scale production and innovation.

Regulations to prevent corporate abuses, ensuring businesses serve public interests.

These lessons remain crucial today. The countries and companies that adapt new technologies, invest in human capital, and maintain competitive markets will shape the next industrial revolution--just as the United States did in the late 19th century.

As we continue studying economic history, we must ask: where will be the "furnace where the future is forged" in the 21st century?

References:

Allen, Robert C. 2011. Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. <https://archive.org/details/globaleconomichi0000alle>. Ch. 4 (“The Ascent of the Rich”).

Boyer, Paul S. 2012. American History: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. <https://books.google.com/books/about/American_History.html?id=C6B13ky6vkQC>. Chs. 5 & 6 (“Industrialization & its consequences” & “Reform & War”).

Chandler, Alfred D. 1992. "Organizational Capabilities and the Economic History of the Industrial Enterprise." Journal of Economic Perspectives. 6 (3): 79--100. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.6.3.79>.

Friedman, Walter A. 2020. American Business History: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press. <https://academic.oup.com/book/28380>. Chs. 4, 5, & 6 (“Railroads & mass distribution, 1850–1880”, “An industrial country, 1880–1910”, & “Modern companies, 1910–1930”).

Gordon, Robert J. 2016. The Rise & Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. <https://archive.org/details/risefallofameric0000gord_w5w7>.

Kuznets, Simon. 1971. “Modern Economic Growth: Findings and Reflections.” Nobel Prize Lecture. December 11 <https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1971/kuznets/lecture/>.

Lots of good stuff here. One more for the list: urbanization, especially in the Midwest. "When Midwestern Cities Were the Richest in the Nation." https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/17/article/912202

a) I do not see the relation of Hamiltonianism (in the sense of using tariffs to promote certain industries over others, “Industrial policy”) to the institutional development outlined.

b) Even viewed as tariffs being the only source of revenue for useful public investments or Tariffs as a quasi-optimal export tax on US raw materials exports (and a way of sticking it to the slaveholding South), the link to institutions seems tenuous

c) If there is a link through b) you need to thoroughly differentiate it from a), which is the commonly accepted meaning of Hamiltonianism

d) How much of an advantage was the size of low cost transpiration accessible, no internal barriers markets to US success?

e) Shouldn’t the focus of contrast with UK and similarity with Germany Japan) be on institutional differences, not just the outcomes?