DRAFT: Talk on “Grand Narratives” & “Slouching Towards Utopia"

For presentation 2022-11-19 Sa at the SSHA Conference

FOCUS: DRAFT: DeLong: SSHA Session: Introduction:

Thank you very much. One of the great things about having finally managed to get this book out into the world is to discover how many friends I have, the book has, and economic history has—how many people are interested in thinking and thinking hard about what we know about the long run shape of human economic history.

What are the stories we should tell ourselves about the very long run? What do we know about the very long-run shape of human economic history?

We think that people became markedly less fit after the coming of agriculture.

We think pre-industrial rates of population growth were absurdly, ridiculously low given human fertility, the patriarchal imperative to have surviving sons, and the fact that approximately a third of humans wound up without such.

(1) and (2) together give us a picture of a humanity after the coming of agriculture and before the coming of modern economic growth that was desperately, horribly poor.

And we can discern no visible trend in material standards of living for typical humans until relatively late in the early modern age.

Humans are productive. Ideas are productive, capital is productive, and resources are scarce.

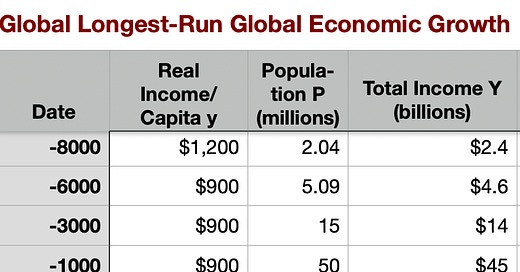

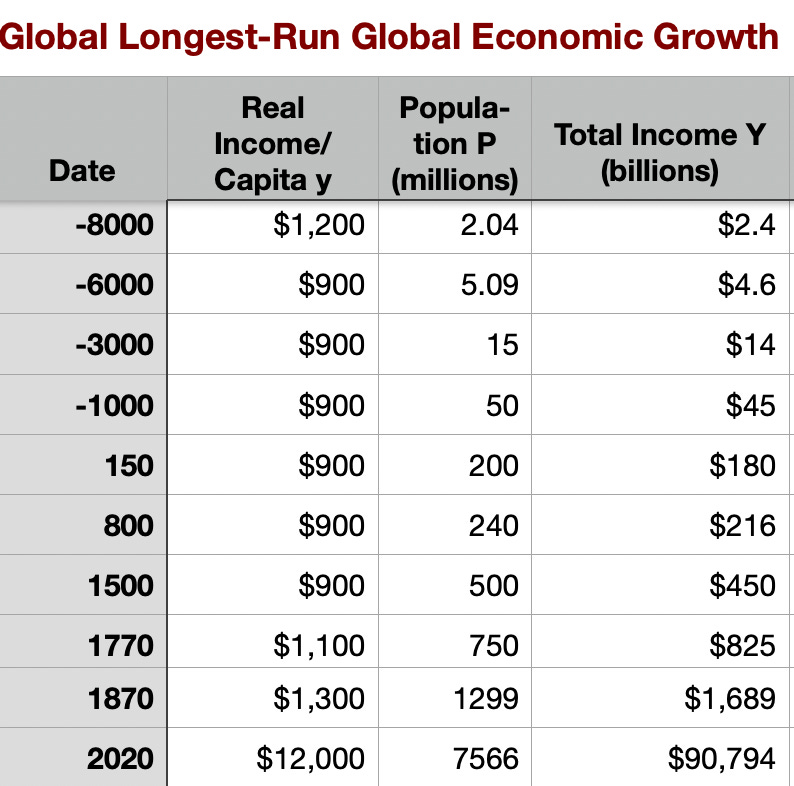

We have our guesses as to human populations and standards of living, for what they are worth. Parenthetically, let me draw your attention to what I think are the two greatest uncertainties in these guesses.

The first is the population of humanity around the year –1000. Is it the approximately fifty million that McEvedy and Jones assigned to it long ago, and that most other people since have followed them in adopting, or is it the hundred million or so that the HYDE people have settled on? This makes a substantial difference with respect to how one views the Iron Age vis-à-vis the preceding Bronze Age.

The second is that our guesses of material living standards are more-or less-at factor cost, when what we really wish for is estimates of user benefit. The ratio of user surplus to factor cost is highly unlikely to be constant—especially when we compare constant returns to scale rival commodities with those produced with strongly increasing returns.

Putting these two issues to the side, our guesses are what they are:

Let me claim, further, that, at world scale, fluctuations in the human economy’s capital-intensity are relatively unimportant, so that the predominant factors affecting human productivity and standards of living are (a) successfully deployed-and-diffused ideas (about manipulating nature and cooperatively organizing humans) on the one hand and (b) resources per worker on the other. I guess that a measure of the value of the deployed-and diffused-human ideas stock H = y√P: average real income per capita times the square root of population.

Why the square root?

Well to take the value of human ideas H to be average real income times population raised to the zeroeth power would be to say that resource scarcity is not a thing. That is false. To take average real income times population raised to the first power would be to say that humans are not productive. That is also false. The square-root—raised to 1/2 power—is in between.

If anyone has a better idea, I would happily adopt it.

So then what do our guesses about average real income and population give us in terms of guesses of the value of the human ideas stock H? This:

What story does this table tell?

It tells a story of:

humanity, ensorcelled by the Devil of Malthus, trapped in dire poverty, with technology growth exceedingly small by our standards until at least 1770, on a world scale at least.

humanity desperately poor, spending hours a day thinking about how hungry you are poor, watching half your babies die, before 1870.

after 1870 wealth and productivity explode; indeed, people looking back a generation or two later talk about 1870 as the beginning of “Economic El Dorado”.

after 1870 the demographic transition spreading from being a Franco-Belgian peculiarity to eventually cover the entire world.

after 1870 it becomes becomes clear within a generation or two that humanity, is for the first time in history, possessed of the prospect that it will relatively soon have the productive mojo to bake a sufficiently large economic pie for everybody to have enough.

Thus before 1870 the road is closed, and after 1870 the road to utopia opens, or ought to have opened after 1870. With the problem of baking a sufficiently large economic pie being solved, what remains are what our predecessors would have seen as the second-order problems of slicing and tasting the pie—of equitably distributing it, and of utilizing our fabulous wealth to live “wisely and well”. With baking solved, the problem of attaining utopia were then, in the eyes of previous generations’ thinkers like Francis Bacon, simply second-order problems.

Most of what made human humanity poor, and human life nasty, brutish, and short, back before 1870 was our inability to bake a sufficiently large economic pie for everyone to potentially have enough.

But in addition, piling Pelion upon Ossa and making life nastier, britisher, and even shorter, were the consequences of that poverty. The only way to get enough for yourself and your family back then was for you to constitute yourself as part of an élite and successfully run a domination-and-exploitation game on the rest of humanity. Thus governance and politics were primarily dissipative, destructive of much of the wealth that was created. For rulers and élites, those in charge and their bully-boy thugs-with-spears (and later thugs-with-gunpowder weapons), assisted by their tame accountants, bureaucrats, and propagandists, reaped where they did not sow and gathered where they did not scatter, and consumed much more of society’s potential energy in their force-and-fraud machines than they were ultimately able to consume.

That was much of what was wrong with human society back before 1870.

It would not, back then, have seemed unreasonable to expect that those force-and-fraud exploitation-and-domination machines would go away once an economy pie large enough for everyone to potentially have enough was bakeable.

We are well on the way to baking the sufficiently large economic pie. Here we are. It is 15 degrees Fahrenheit outside. We are not huddled under every blanket we can pile together, but are, if anything, slightly too warm here inside, because the hotel is overheated while I at least am in clothes that were made for Scotland in 1651, back when the closest equivalent to a source of gortex you have is a sheep.

Yet, in spite of our wealth fabulous in historical perspective, what were supposed to be second-order problems—the problems of slicing and tasting the economic pie, of equitably distributing and properly utilizing it so that people feel safe and secure and are healthy and happy—continue to pretty much flummox us.

In large part. they flummox us because technological progress is so fast. very single generation we have Schumpeterian creative destruction revolutionizing economy and society. Every generation it gives us a brand-new set of forces-of-production hardware. We then have to frantically write new socio-econo-political-cultural relations-of-production, -communication, -organization, -and-so-on software to run on top of it so the whole thing doesn’t crash. We try to figure out how to get the proper benefits of decentralization and incentivization on the one hand, while on the other hand not reducing society to a state where the only rights that are recognized are property rights and thus the only people who have any social power are those who have been lucky or who chose the right parents.

Those were the conclusions I arrived at after making up this table, and then staring at it for a good long while.

Now we could look backward from 1870: asking the question of how we got to the point of explosion. We could look forward from 1870: asking about the working-out of the logic of unprecedented, revolutionary, economic growth generation after generation, and that growth’s political-economy consequences.

I wound up writing a book looking forward from 1870 at the political-economy consequences.

I still regret not also managing to write the Landes-Schumpeter, book about the working out of the process of economic growth after 1870.

And I mourn my inability to write a comprehensive book looking backward from 1870 about how we got to the point of explosion. But I am cheered by noting that, this year alone, each in their own way, Oded Galor and also Mark Koyama and Jared Rubin have published very good works of synthesis on these questions.

But there is another question, about the extent to which we should take 1870 to be in some sense the hinge of history.

Matthew Yglesias informs me that Robert Nozick, when he died, was trying to develop a philosophy of counterfactuals: to distinguish sharply between “causally thin” and “causally thick” processes.

Mostly, Matt thinks, this was because it amused Nozick to troll other members of the Harvard faculty with respect to the trajectory of Marxian Socialism—Nozick maintained that:

A Russian revolution was causally-thick, in that there is no reasonable counterfactual in which Russia does not have a revolution after 1900;

A Leninist Russian revolution, was causally-thin, in that it is easy to think of counterfactuals in which the Bolsheviks are forgotten well before 1930, and quite difficult to see the stabilization of the really-existing socialist Leninist Bolshevik regime as anything but the most freakish and unlikely mischance;

However, conditional on Leninism, the emergence of something like Stalinism is another causally-thick process, for there no reasonable counterfactual in which Lenin’s regime is not followed by a larger disaster.

Indeed, Max Weber predicted this in 1918. When Joseph Schumpeter said that the Leninist Russia would be an “interesting laboratory” for experiments in economics, Weber is said to have roared back: "a laboratory littered with human corpses!” and then stormed out of Vienna’s Café Central, or so the story goes.

Suppose we apply this Nozickian framework to human economic history. Two natural questions are:

Was the explosion of wealth and productivity of 1870, the Second industrial Revolution, the one big wave of Robert Gordon, causally-thin, in the sense that institutions had to evolve then in a way that was unlikely to get the explosion?

Was the actual causally-thin nexus, instead, or nexuses earlier?

Could we very easily have avoided the last few institutions need to support the Second Industrial Revolution and Modern Economic Growth falling into place in 1870? Simon Kuznets was very firm that Modern Economic Growth was a different animal than what was going on during the British Industrial Revolution. In the British Industrial Revolution era of 1770–1870 world technological progress was perhaps a hair less than 0.5% per year. With the processes then ongoing pre–1870, it seems more likely than not that post–1870 technological progress would have been slower than that. A lot of global growth in deployed-and-diffused technology over 1770–1870 comes from the globalization-driven concentration of manufacturing worldwide into the districts in which manufacturing was most productive, largely the British Midlands. You can only do that once. A lot of global growth in the power of deployed-and-diffused technology over 1770–1870 came from its complementarity with stored sunlight in the form of coal and from the fact that the last round of glaciers had been bulldozers that scraped off post-carboniferous rock and gave us really cheap coal at sea level where it could be floated anywhere for pence. As of 1870 that coal was running out; William Stanley Jevons made his first splash in economics by pointing that out.

If Jack Goldstone were here, he would probably make his argument that the British Industrial Revolution is perhaps viewed as the last “efflorescence”. Had post–1870 technological growth fallen back from its 1770–1870 pace, we might now be sitting here with the technologies of 1903 trying to support our same world population of 8 billion. We would then be much, much, poorer. We would be sending people by the tens of thousand to islands in the South Pacific with pickaxes to mine guano.

Was the Second Industrial Revolution an eye-of-the-needle event?

Earlier this fall at Berkeley the extremely learned Robert Brenner said “no”. He lectured me for 45 minutes about how the true causally-thin nexus came much earlier: the emergence, in the two centuries after the Black Death, in the 300 mile-radius circle around Dover, of market-bourgeois class relations, and thus the transformation of (a) a society of peasants, knights, lords, and the occasional merchant into (b) a society of laborers, craftsman, merchants, farmers, landlords, mercenaries, and plutocrat-politicians. After that it was baked in the cake. And it is entirely right and just that Robert do this. He has, after all, been writing this since I was 15. Indeed, I remember, back when I was 20, David Landes telling me: you need to pay a great deal of attention to Robert Brenner.

Some here say that the causally-thin counterfactual nexus word was the founding of the Royal Society and nullius in verba, “nothing by word”. This shift from (a) ideas spreading primarily because they are useful to an upper class élite running a force-and-fraud domination-and-exploitation scheme on the rest of society, to (b) ideas spreading because they are true of empirical reality.

Others would talk about how the true truly unusual Nexus is the development of an extraordinary level of social trust.

Others might go back to the Emperor Heinrich IV Salier, reportedly standing in the snow outside of the castle at Canossa in 1077, and the establishment of the principle that the law is not just a tool for but binds even the most powerful.

Or you might even go back to the emergence of a strict monotheism—a God focused not on this world but on heaven and hell—in which case in this world one should praise the Lord, yes, but what is important here and now is to pass the ammunition.

What is the best narrative, the best grand narrative, for human economic history? Or what is the best grand narrative for us? Or are we better off without grand narratives at all? Might this whole project simply have been ill-advised?

Maybe it is subsumed in causally thin/thick, but development of knowledge is something that has to be invested in.

I'm sympathetic to identifying the Scientific Revolution as the key. But then I remember that technology is endogenous and I doubt myself. Was technology endogenous in 1700? In 1825? I don't know.

Other than that possible quibble, you have it right.