DRAFT: Þe First Inflation Problem of þe 21st Century

As of 2023-01-20: My guesses as to the form and shape of the inflation process currently going on in the United States, and my guesses as to the proper stance of monetary policy right now. A draft...

Perhaps there was progress in macroeconomics back before 1940. Certainly by 1940 it was the consensus of economists that the claim of Josef Schumpeter and others that depressions were a necessary "functional" part of capitalism—an inevitable concomitant of adjustment to change in the creative-destruction process of modern economic growth—was dead as a doornail. It was 131 years since John Stuart Mill had first argued that “general gluts” excess supplies of pretty much every produced commodity and of labor, are the flip side of an excess demand for money.

It had taken 131 years to achieve this consensus. It was achieved only after the rude interruption of the discourse of economic theory by the Great Depression. There were unsettled questions about which aspects of money were key to the destructive excess demand—liquidity? safety? collateralizable nominal value? Its use as a savings vehicle? And there were unsettled questions about whether central banks performing open-market and lender-of-last-resort operations could do the stabilization policy job, or whether a somewhat comprehensive socialization of investment would be required.

Since then, however, whether there has been significant progress is doubtful. Alan Blinder's new A Monetary and Fiscal History of the United States, 1961-2021 describes a game of constant musical chairs without the number of chairs ever decreasing, or perhaps a game of whack-a-mole:

of wheels within wheels, spinning endlessly in time and space … [with] certain themes … waxing and waning … monetary versus fiscal … the intellectual realm … the world of practical policy making … the repeated ascendance and descendence of Keynesianism…

E3, E4, E5, N1; inflation, monetary economics, monetary history

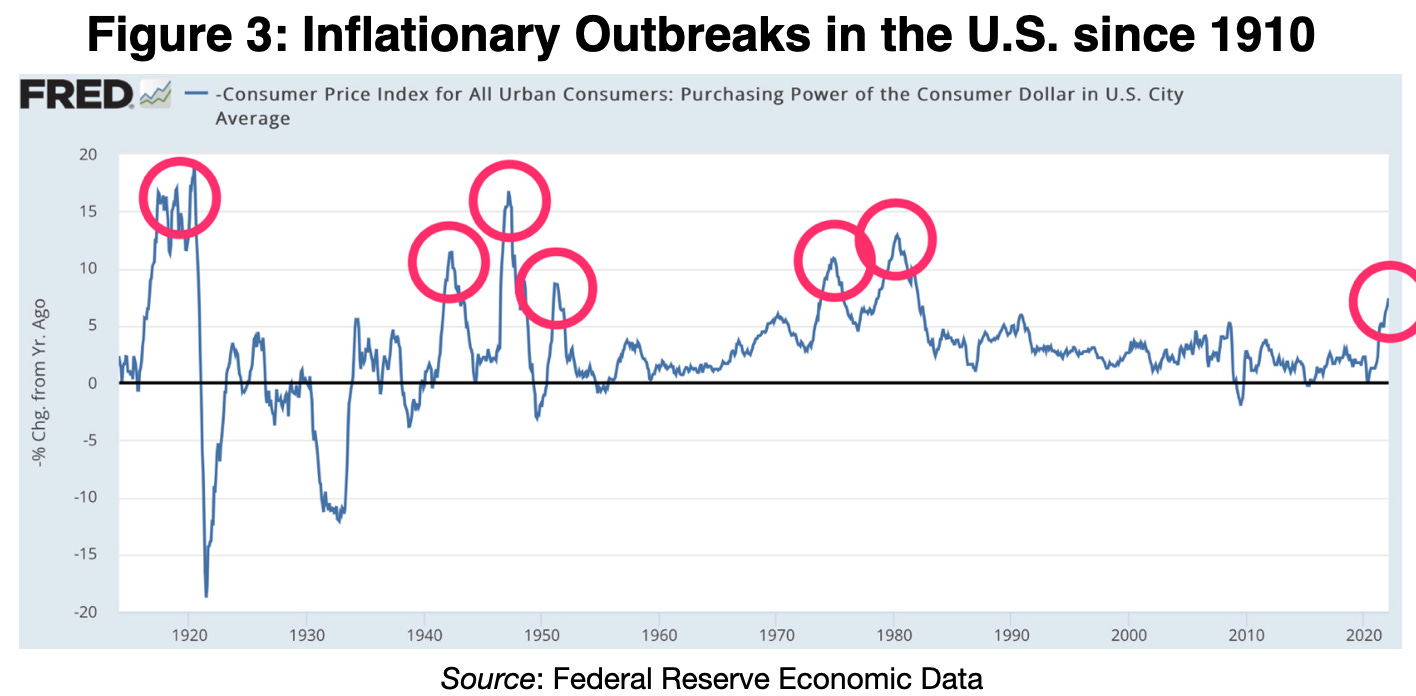

Abstract: Inflation in America after WWII It peaked at 19.7% in the twelve months to March 1947. America’s economy reoriented itself from its wartime to its post-war structural configuration. The Federal Reserve did nothing at all. Inflation went negative in 1949 with a minor recession came. The fourth episode came in 1951, and was in some ways a reverse of 1947—not a demobilization but a remobilization inflation. Again, the Federal Reserve did nothing. And, again, the inflation wave passed. And then came the long siege of moderate inflation that took place between 1966 and 1984, as the Federal Reserve dithered before the Volcker disinflation. What policy you think would have been and will be appropriate for the Biden administration and the Yellen-Powell Fed depends on which of these past historical episodes provides the best model and analogy for the state of the US economy today. The odds right now seem to me to be on the first two, rather than the third…

The Fed may need to call it a day and soon. The annualized rate of headline CPI inflation in Q4 of 2022 was about 3.1% and that of Core CPI inflation was about 4.4%. And as Christie Romer points out, we may not have started to see the lagged effects of the monetary tightening yet.

I see that for December, average weekly earnings are down from the previous month. Retail sales excluding gas and autos are down from the previous month. Freddie Mac's national house price index is down for its 5th straight month. Apartment Lists national rental price index has fallen for its 4th consecutive month. Core CPI is up 3.7% annualized from the previous month, but is negative if the highly imputed and lagged Shelter component is excluded.

And we're really considering raising interest rates because core services less housing inflation is too high? Q4 PCE data isn't out for a week, but Q4's CPI services less shelter is 0.9% annualized.

What am I missing? Is everyone else looking at Year over Year data?