DRAFT: Why Have Superhigh Long-Run Stock Returns in America Persisted?

For my August Project Syndicate column...

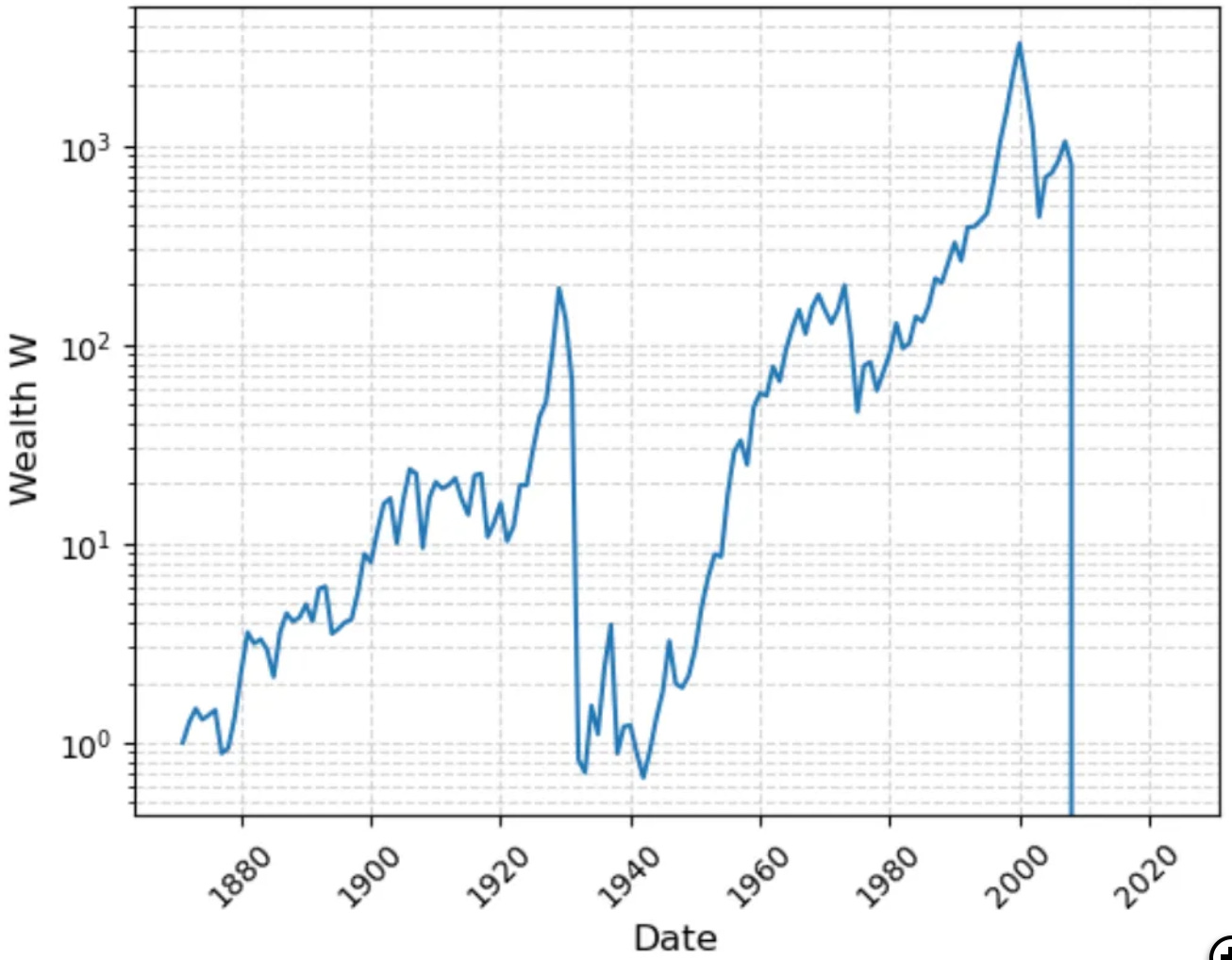

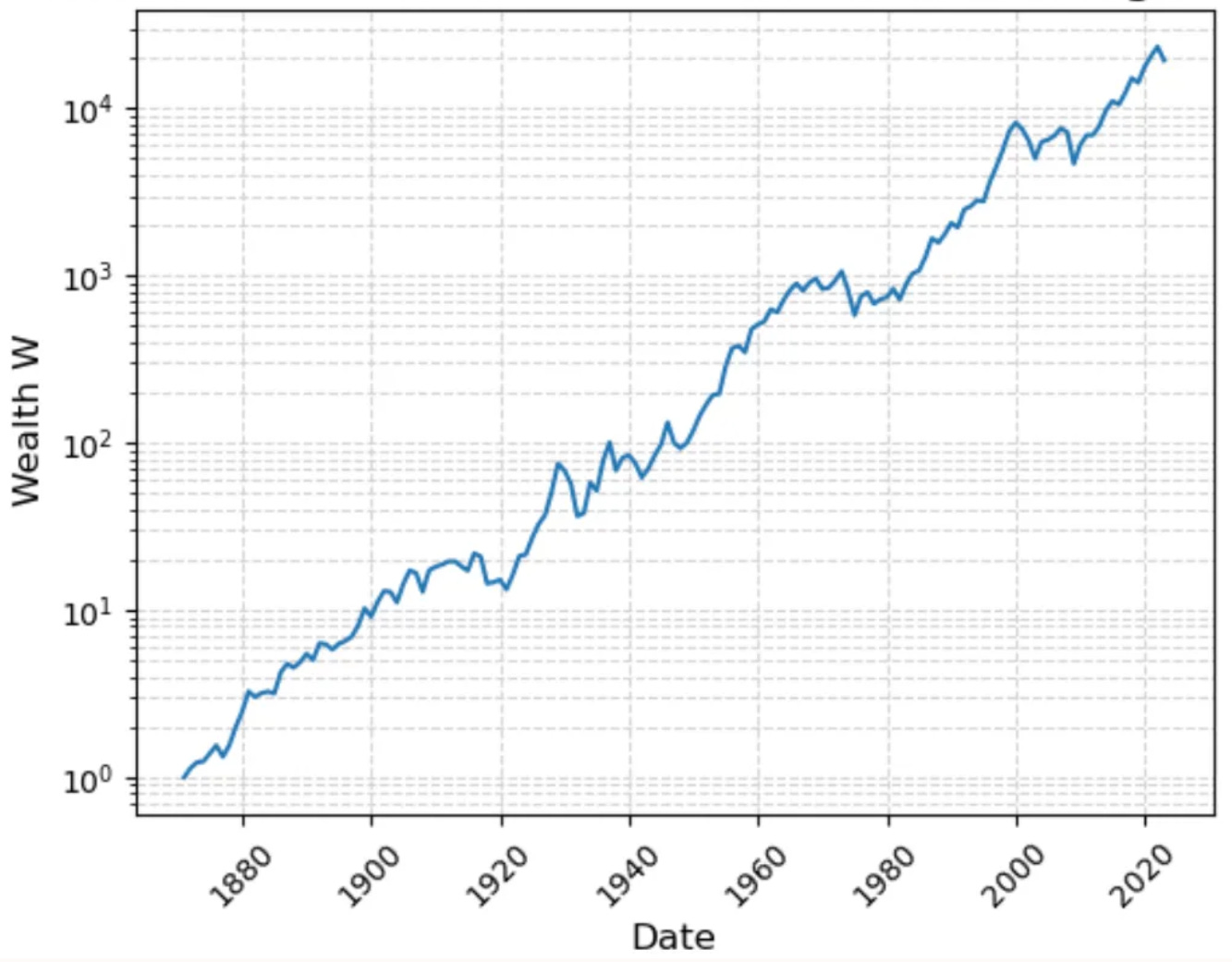

Suppose that you had started in January 1871 and had invested your wealth in the stock market—in a broadly diversified set of common stocks. Suppose that, as dividends rolled in, you had reinvested them in your portfolio. Suppose that every January you had rebalanced—sold winners and bought losers so as to maintain your diversification. Suppose that you had paid no taxes, and had incurred no transaction costs. Then, for Robert Shiller's version of a diversified stock portfolio, and adjusted for inflation, as of last January you would have 65,004 times your initial wealth investment. By contrast, if you had performed the same portfolio investment experiment, but with long-term U.S. Treasury bonds, you would have 41 times your initial wealth. 65004 to 41. An average geometric real return for stocks of 7.3% per year, and for long bonds of 2.5% per year: an average gap of 4.8%-points per year. This is the "equity premium puzzle" of Rajneesh Mehta and Edward Prescott.

Now, in real life, nobody could actually execute either of these strategies. The commissions you must pay and the price pressure, your sales and purchases exert when you sell winners and buy losers to keep your portfolio rebalanced take a haircut. Taxes take a bigger haircut: they are levied on your interest income from bonds, on your realized capital gains from stocks, and—back in the day when share repurchases were highly disfavored—significant taxes were always owed on the dividends that were companies' way of getting money out of the corporation and to shareholders. These factors took a haircut of perhaps 1/3 of your real return from diligently following either strategy. So figure a real return gap of 3.2%-point per year.

But an average real return gap of 3.2% points per year means that an investor in stocks doubles their money relative to an investor in bonds in, on average, 69 ÷ 3.2 = 22 years.

Before the mid-1920s, when Edgar L Smith wrote his "Common Stocks as Long-Term Investments" this fact about stock and bond investors was not widely known. People had focused on the returns to individual stocks, and on the high likelihood that any single corporation would fail to maintain its position in the marketplace over any extended period of time, and hence lose its investors' money. stocks were highly "speculative". They were for gamblers, for insiders with special information, for those who really believed they had special insight into the business cycle and so could time the market—and for those afflicted with Dunning-Krueger syndrome who thought they were much smarter than they were, and whose losses powered the gains of the successful professional equity traders.

But what was true of one stock was not true of a large and properly diversified basket. To a large degree, risk spread across companies was risk eliminated. And long-term diversified stock market investments had other risk-reducing advantages that those who focused on short-term individual company stock performance did not see. To a substantial degree, the workings of the semi-regular business cycle meant that low cash flows from a company this year would be offset by higher cash flows three, five or ten years from now. And, to an overwhelming degree, changes in valuation ratios—in how much of a multiple of average expected future earnings and dividends the market would be willing to pay—would reverse themselves in the future, and so a truly long-term diversified investor would be wise to ignore market fluctuations and transitory blips to earnings, and simply trust in the long-term profitability of the business.

Moreover, were bonds ever in any real sense safer than stocks? Bonds are extraordinarily vulnerable to inflation, and most of the things one can think of that do substantial permanent damage to business profitability derange government finance to a much greater degree—and are almost invariably followed not by a small inflation like 2021-2023 or a moderate inflation like 1968-1983, but a bond-wealth destroying inflation.

And yet the return gap persisted across the generations. A stock investor ending their 40-year career in 1910 would have, pre-tax and -transaction costs, 3 times the wealth accumulation multiple of a bond investor. One ending their career in 1950 would have the same. Ending in 1990? Twelve times forty years earlier. And over 1990-2023? Four times.

Past performance is never any guarantee of future results. But it remains the case that in a typical year, business earnings, or at least 4% of stock, market equity value, well bond returns are lucky to be 2% above inflation. There is this a very strong sense in which it is much harder to raise money on the stock market then it should be, and that American business is hobbled thereby.

But if stocks are such a good deal for the long run, why are our investors in the stock market not richer? Well, to a substantial degree they are: remember the 65004-to-41 wealth gap since 1870 from the thought experiment at the beginning. Or look at the career of Warren Buffett and his Berkshire-Hathaway.

But there is a reason why they are not even richer. It takes time for the law of averages to work itself out. And "average" is only "typical" if you have that time. If you lose your stake and cannot continue to play, you do not have that time. Mathematically, your strategy may have had a high expected return. But the typical investor who undertakes that strategy never sees that expectation. Investors in the stock market holding their portfolio from January to January who extended themselves too far and who, say, borrowed $1.50 on each $1 they had and invested it in the market—they have gone spectacularly bankrupt twice since 1870: in 1931, and in 2009.

Past performance paragraph needs work.

Firstly, what exactly is Shiller's diversified stock portfolio. It certainly seems to have a lot more growth in the early years than say the S&P500, so is that growth due to high dividend payouts? The 1929 crash is hardly noticeable in his portfolio, yet huge in index prices. [Should those stockbrokers not have jumped?]

If your portfolio had stocks that went bankrupt or were merged in the year of holding, how do you buy them to rebalance the portfolio? A merger has already extracted that value for the "winners". An index just replaces that stock with a new "up and comer".

We do know that stocks are riskier than treasuries, and that junk bonds are riskier than treasuries. What exactly is the acceptable risk premium? Is it just a judgement of the participants, or some sort of pareto value for the slope of the risk premium?

Not everyone has the same investment goals. Pension funds need as much predictability as possible, so bonds are the preferred vehicle. That reduces bond returns if there is competition for the bonds. Historically defined pension plans were a major buyer of such investments. That has changed since those plans have largely disappeared except for government employees.

Bottom line is that I am not confident that the claimed "excess risk premium" is real and may be an artifact of index construction and other factors. Shiller is in effect claiming the market is inefficient. I don't believe it. If it was, there would be a lot more equity investors making out like bandits on the quiet.