Þe Music to þe Zombie Dance of Human Society Changes Its Key

Algorithm replacing global value-chain, which replaced mass-production, which replaced applied-science, which replaced imperial-commercial, which replaced Mediæval, which replaced classical-ancient...

A very interesting piece thinking about how we should think about understanding our changing and strange society, as we rapidly move into the Info-Biotech Age:

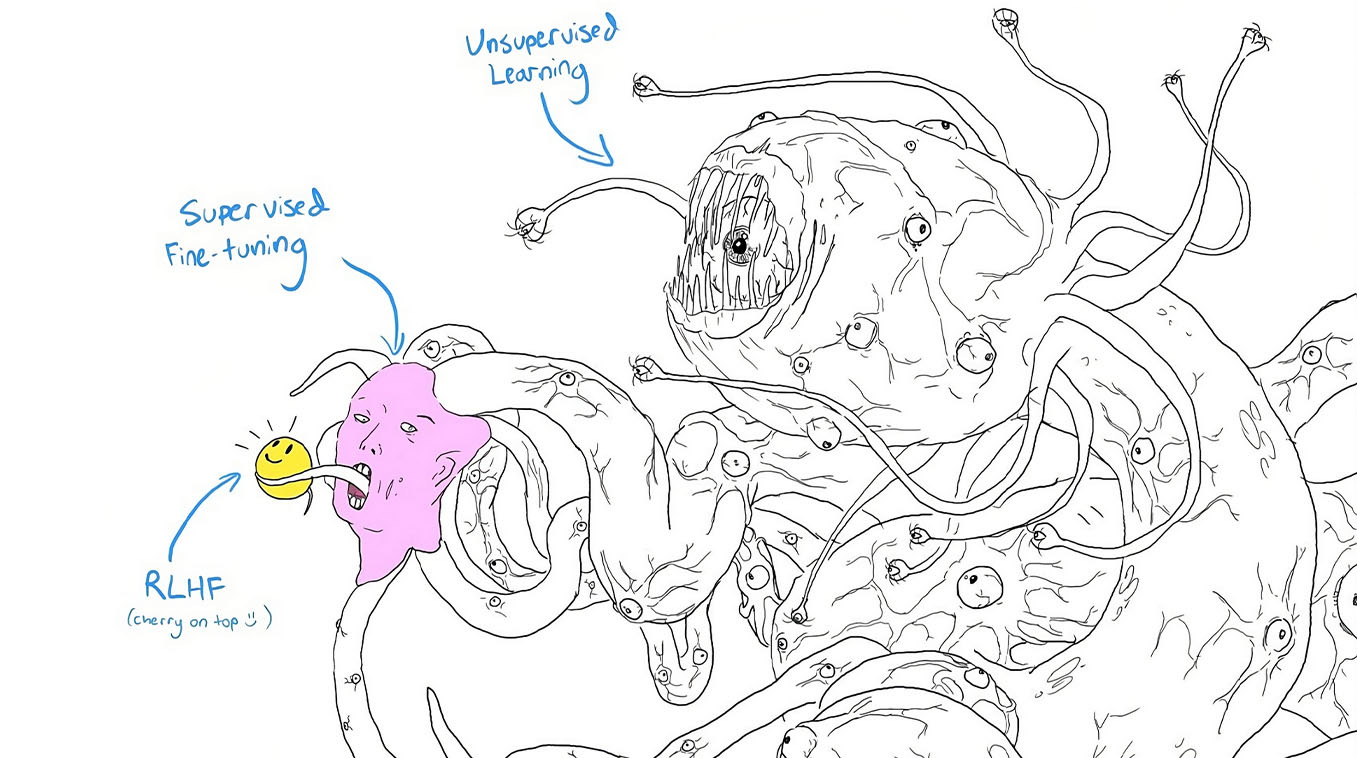

Henry Farrell & Cosma Shalizi: Artificial Intelligence Is a Familiar-Looking Monster: ‘"Shoggoth[im]"... artificial servants that rebelled against their creators.... We've lived among shoggoth[im] for centuries... "the market system", "bureaucracy" and even "electoral democracy".... Enormous, impersonal distributed systems of information-processing that transmute the seething chaos of our collective knowledge into useful simplifications....

[1] Hayek argued, any complex economy has to somehow make use of a terrifyingly large body of disorganised and informal "tacit knowledge" about supply and exchange.... The price mechanism... summarise[s] this knowledge and make[s] it actionable. A maker of car batteries doesn't need to understand the particulars of lithium-processing. They just need to know how much lithium costs, and what they can do with it.

[2] Likewise... Scott... bureaucracies are monsters of information... excreting a thin slurry of abstract categories that rulers use to "see" the world.... Markets and states... inimical to individuals who lose their jobs to economic change or get entangled in the suckered coils of bureaucratic decisions... incapable of caring if they crush the powerless or devour the virtuous....

[3] It is in this sense that LLMs are shoggoth[im]... [Gopnik] "cultural technologies" which reorganise and noisily transmit human knowledge... wear more human-seeming masks than markets and bureaucracies, but they are no more or less beyond our control. We would be better off figuring out what will happen... than weaving dark fantasies about how they will rise up against us....

Weitzman... planned economies might use... "separating hyperplanes" to adapt.... Machine learning can find such hyperplanes.... LLMs might give bureaucrats new tools for adjudicating complex situations... summarise complex regulations or provide recommendations about how to apply them to novel situations.... LLMs don't leave paper trails. But that might not stop their deployment.... Researchers talk about substituting LLMs for opinion polls.... You can interrogate LLMs more dynamically....

The modern world has been built by and within monsters, which crush individuals without remorse or hesitation, settling their bulk heavily on some groups, and feather-light on others. We eke out freedom by setting one against another, deploying bureaucracy to limit market excesses, democracy to hold bureaucrats accountable, and markets and bureaucracies to limit democracy's monstrous tendencies. How will the newest shoggoth change the balance, and which politics might best direct it to the good? We need to start finding out. …

What is my take on this—on how we are constrained, and thus alienated, by alien powers that we do not understand, cannot control, and that are cold and indifferent to us even though they are the products of our own minds and are, in fact, composed of our own individual human actions as they are patterned by our societal institutions and our cultural practices?

Let me take a step back, and take the long view of human history. Start 750,000 years ago:

Joseph Henrich: The Secret of Our Success: ‘Between the Golan Heights and the Galilee mountains… Gesher Benot Ya'aqov… 750,000 years ago…. Hearths and areas for both stone-tool manufacturing and food processing… fire and… hand axes, cleavers, blades, knives, awls, scrapers, and choppers… [of] flint, basalt, and limestone, [with] tool manufacture… done on-site, often from giant slabs carried in from a distant quarry by a team… [and] us[ing]… levers as part of the quarrying process. The basalt is of the highest quality and well quarried, suggesting that someone had a storehouse of know-how…. The inhabitants…also, somehow, obtained freshwater crabs, turtles, reptiles, and at least nine types of fish, including carp, sardines, and catfish…. There were seeds, acorns, olives, grapes, nuts, water chestnuts, and various other fruits… includ[ing] the submerged prickly water lily…. Cumulative cultural evolution is up and running at this point, generating more know-how than you, me, or our lost European Explorers could have ginned up in a lifetime…. In the next 300,000 years… Homo erectus changed sufficiently, including a brain expansion to 1200 cm3, to justify a new species name, Homo heidelbergensis… projectile weapons, including wooden throwing spears with stone points… a variety of techniques for producing stone blades… consistent within sites or populations but did vary between populations. Distinct tool traditions and composite tools that exploited natural glues weren’t far behind…

By 750,000 years ago the homo erectus version of the East African Plains Ape—that is, us—had become a limited time-binding anthology intelligence. As long as it could be transmitted through culture, what one person in the band of fifty or so knew, everyone else could learn. Moreover, what one ancestor had known or what one member of a neighboring band knew, if it were useful and if it could be incorporated into the culture, the entire band could learn. And in addition, there was the division of labor, so that every East African Plains Ape did not have to learn everything—which, of course, nobody could. We as an anthology intelligence were very smart and knowledgeable. We as individual East African Plains Apes were pretty dumb. We still are. Even today, with our brains of 1400 ml twice as large as those of homo erectus, we are lucky if we can remember in the morning where we had left our keys last night,

Time passed. Evolution—biological and cultural—continued. Language emerged, a truly powerful force multiplier raising the thought capabilities of the anthology intelligence that was a human group to an exponential degree. We spread out all over the world, and our population grew, and grew denser. And our means of communication and interaction to enable the anthology intelligence to think and to construct a productive division of labor became more complicated, and more varied.

More-or-less in order, we developed the productive (and unproductive) anthology intelligence-intensification communication technologies of:

Language

Writing

Printing

Mass media

Social media

Algorithmic feeds

And we developed the social-organization cultural technologies of:

Dominance

Prestige

Reciprocal gift-exchange

Redistribution

Propaganda

Charisma

Honor

Market economy (which is something much more than reciprocity)

Bureaucracy (which is something much more than redistribution)

Algorithmic classification

That is the latest stage of our cultural evolution, with modern Machine Learning being the current fullest flowering of the societal-organization cultural technology of the algorithm, for both information and communication—determining what each individual not-so-smart East African Plains Ape will see and hear—and for classification—determining what each individual not-so-smart East African Plains Ape will have in the way of resources and be constrained with respect to his or her potential actions.

How to make sense of this? One way would be to think in terms of modes: modes of communication, production, distribution, and, yes, domination, as human history proceeds:

Hunter-Gatherer (-10000)

Tribal-Agricultural (-5000)

Bronze Age (-3000)

Classical-Ancient (-500)

Mediæval (1000)

Imperial-Commercial (1600)

Steampower (1880)

Applied-Science (1915)

Mass-Production (1950)

Global Value-Chain (1990)

Info-Biotech (2025)

With each mode generating a different set of possibilities for the kinds of societies that can be built on top of it. And, moreover, things are massively complicated by the fact that different modes overlap—within countries and, much more, around the globe. America today, for example, is an overlapping mix of Info-Biotech, Global Value-Chain, and Mass Production modes. And in the world—well, there are still people, close to a billion of them, whose lives are underpinned by a combination of the modes all the way back to the mode that was characteristic of the Imperial-Commercial Age of around the year 1600.

Oh, this is the overarching framework into which I would put what Farrell and Shalizi (and Henrich, and Gopnik, and Scott, and von Hayek) were, and are, trying to do.

I do have one (and only one) substantial criticism of how Farrell and Shalizi are presenting the issues: they are pessimistic. They, mostly, fear our shoggothim that we have constructed, and that have escaped our control. They fear them as threats to our ability to be free through the constraints they impose on us, and as things that crush us in their unconcern. That is a third of the story. But there are another two-thirds. They massively empower us, individually and collectively, in that they make us collectively so productive. And they massively empower us, individually and collectively, in that they make us collectively so intelligent.

A decade ago both Farrell and Shalizi quoted Francis Spufford on the underlying problem and our vain dreams for a solution:

Marx had drawn a nightmare picture of what happened to human life under capitalism, when everything was produced only in order to be exchanged; when true qualities and uses dropped away, and the human power of making and doing itself became only an object to be traded. Then the makers and the things made turned alike into commodities, and the motion of society turned into a kind of zombie dance, a grim cavorting whirl in which objects and people blurred together till the objects were half alive and the people were half dead. Stock-market prices acted back upon the world as if they were independent powers, requiring factories to be opened or closed, real human beings to work or rest, hurry or dawdle; and they, having given the transfusion that made the stock prices come alive, felt their flesh go cold and impersonal on them, mere mechanisms for chunking out the man-hours. Living money and dying humans, metal as tender as skin and skin as hard as metal, taking hands, and dancing round, and round, and round, with no way ever of stopping; the quickened and the deadened, whirling on. … And what would be the alternative? The consciously arranged alternative? A dance of another nature, Emil presumed. A dance to the music of use, where every step fulfilled some real need, did some tangible good, and no matter how fast the dancers spun, they moved easily, because they moved to a human measure, intelligible to all, chosen by all…

And Cosma Shalizi noted:

Marx did not sufficiently appreciate [that] human beings confront all the structures which emerge from our massed interactions in this way. A bureaucracy… even a thoroughly democratic polity… can… be just as much of a cold monster…. We have no choice but to live among these alien powers which we create…. What we can do is try to find the specific ways in which these powers we have conjured up are hurting us, and use them to check each other, or deflect them into better paths.

Sometimes this will mean more use of market… sometimes… removing some… from market allocation… sometimes… expanding… democratic decision-making…. Sometimes… narrowing its scope (for instance, not allowing the demos to censor speech it finds objectionable)…. sometimes… leaving some tasks to experts… sometimes… recognizing claims of expertise to be mere assertions of authority… complex problems, full of messy compromises. Attaining even second best solutions is going to demand “bold, persistent experimentation”, coupled with a frank recognition that many experiments will just fail, and that even long-settled compromises can, with the passage of time, become confining obstacles…

This process Shalizi calls for is, as I wish I had said in my big book (which you all should buy), our process of Slouching Towards Utopia.

I think Cosma and I would say that we are - if not blithely optimistic - certainly in agreement that we can't do without these vast systems, even while we want to resist their encroachments. Really what we are doing here is trying to pivot the debate away from a fight between OMG AGI PAPERCLIPZ-BASILISK-HERE-WE-COME on the one hand, and SOFTWARE-WILL-EAT-THE-WORLD-AND-IT-IS AWESOME on the other to a more specific understanding of the consequences of this new form of representation. I'm guessing that some people will be far more optimistic than we are - others will think that we're not nearly pessimistic enough. But understanding how these work as social systems seems to us to be the first step towards actually getting a real debate going. Thanks for the quick and valuable response!