Fed Overreacting?, & þe Post-1870 Speed of Transformation & Its Consequences, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-07-07 Th

I greatly enjoy and am, in fact, driven to write Grasping Reality—but its long-term viability and quality do depend on voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. I am incredibly grateful that the great bulk of it goes out for free to what is now well over ten-thousand subscribers around the world. But if you are enjoying the newsletter enough to wish to join the group of supporters, please press the button below:

CONDITION: Fed Overreacting Watch

Ms. Market thinks the Fed has overdone it, and will be cutting, and trying to find the nerve to cut more, after February 2023.

Note that it is not Democrats who are making these financial market bets. This is what Republicans with money who are placing it on the line are thinking:

Bryce Elder: A Fed Funds Rate Dislocation: ‘Deutsche Bank strategist Jim Reid…. investors are buying into the short-sharp-shock thesis. Futures are pricing in that US interest rates will peak at 3.39 percent at the February 2023 FOMC meeting, then come back by 0.7 percentage points over the following 12 months… <https://www.ft.com/content/29b568b6-83c5-4c52-a288-78894448386c>

Paul Krugman: Taking the ‘Flation’ Out of Stagflation: ‘Powell acknowledged that this was a preliminary number that might be revised. Sure enough, the number was revised down…. The big story right now seems to be a quite sharp decline in market expectations of inflation over the medium term… supply chain problems… have gone into reverse… evidence that the economy is weakening… it seems reasonable to suggest that inflation will also fall fast. That, at any rate, is what the markets seem to be anticipating… <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/01/opinion/inflation-fed-stagflation-recession.html>

FIRST: The Speed of Transformation Post-1870, & Its Consequences:

Which of the ancien régimes with capitals in Europe managed to avoid revolution and civil war in the transition to “modernity”? 1848 saw only Norway, Sweden, Belgium, Holland, and Great Britain see little unrest. Piedmont—the Kingdom of Sardinia—avoided domestic insurrection by having its ancient régime put itself at the head of the Italian nationalist movement. The Russian Empire escaped radical or nationalist revolution in 1848—Poland had already tried to rebel in 1830. But that there would be a Russian Revolution of some form—more than a series of demonstrations followed by reform or by a coup—seemed very much in the cards. Nobody with a capital outside Europe’s far northwest corner seemed likely to escape.

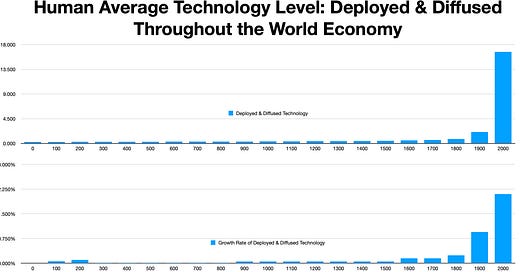

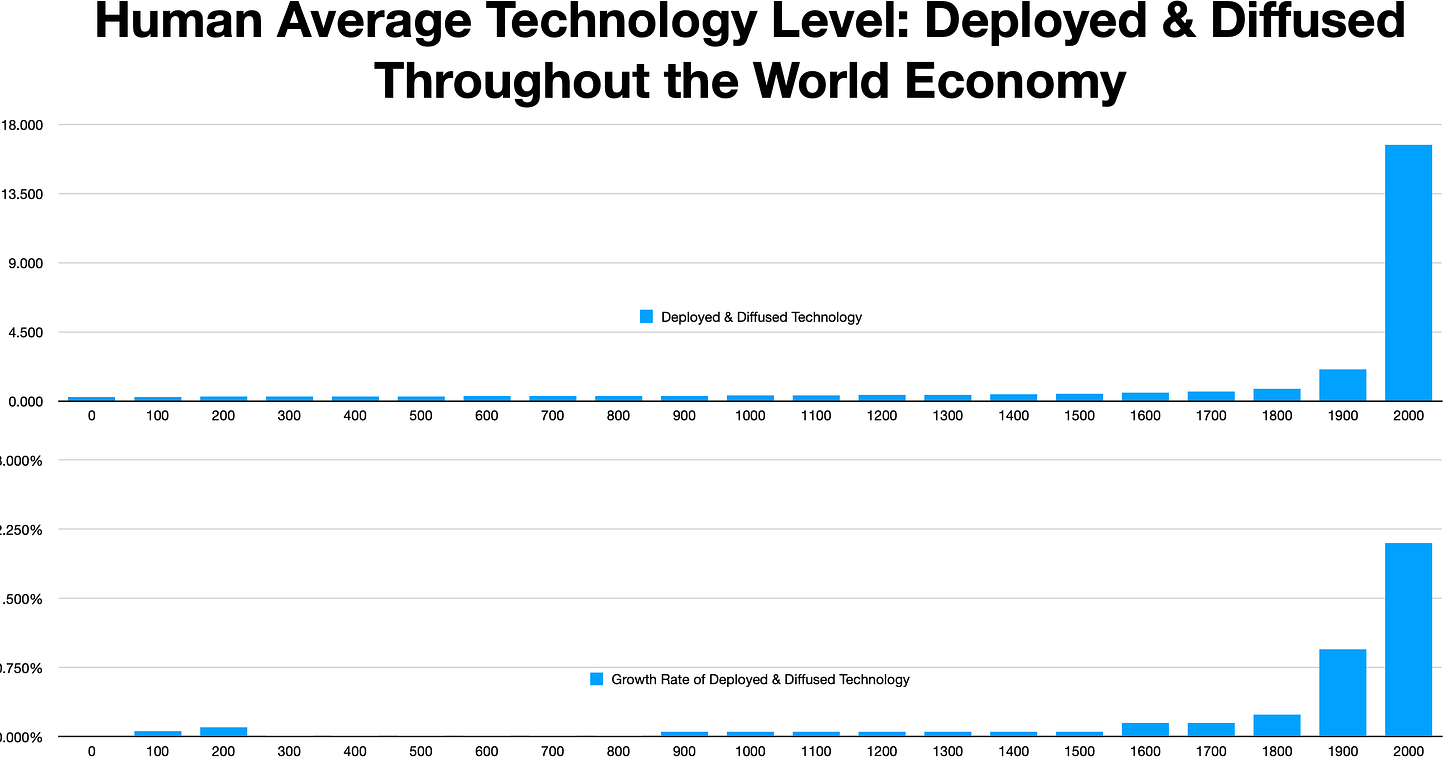

Why? Because even in 1848 the underlying pace of socio-economic change was too great for an ancien régime to maintain its precarious perch. And the pace of global socio-economic change—in the average global technological underpinnings of society—was going to be amped-up by a factor of 4.5 as the world moved from the already extraordinary Industrial Revolution century of 1770-1870 to the post-1870 Modern Economic Growth era. Let’s give the mic to the very sharp Dominic Lieven:

Dominic Lieven: The End of Tsarist Russia: The March to World War I & Revolution: ‘Although the Russian case is unique, in this respect too international comparisons are nevertheless very important. In the two generations before 1914, European society as a whole had been transformed more fundamentally than in centuries of earlier history. It was hard for anyone to keep his balance amid dramatic economic, social, and cultural change; predictions as to where change might lead in the future could inspire even greater giddiness…

LINK: <https://archive.org/details/endoftsaristruss0000liev>

Thus the post-1500 political-socio-economic history of the long 20th century was indeed, as Eric Hobsbawm says of his short 1914-1991 century, the history of an Age of Extremes. But the sheer magnitude of the wealth generated by technology those extremes more extreme on the high than on the low side: much more marvelous than terrible. But the terrible parts were very terrible indeed.

But why did it have to be terrible at all? Why couldn’t increasing wealth simply be semi-equitably distributed, and social and political systems adapt peacefully and gradually to underlying changing patterns of production and exchange and the relationships of social power that those patterns produced? Before 1870 the economy was changing only slowly, too slowly for people's lives at the end of a century to be that materially different from how they had been at the beginning. The economy was thus the painted-scene backdrop behind the stage, rather than the action on the stage.

From 1770-1870 there did indeed come an Industrial Revolution. But at its end, in 1870, in every country the bulk of people were still peasants, craftsmen, and servants working much as their ancestors a century before had done—even though the railroad, the steamship, the telegraph, the automated factory, the furnace, and the steam engine dominated the wealth-creation process. You could hang on.

British politics and governance in 1870 was different from how it had been in 1770, but not as different as the British economy was. French politics and governance had been utterly transformed. But for the other great powers—for their heads Regent Francisco Serrano Domínguez Cuenca y Pérez de Vargas, King Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia, Emperor Franz Joseph Karl von Habsburg, Emperor Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig von Hohenzollern, Sultan Abdülaziz of the House of Osman, and Czar Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich Romanov, and for all their ministers, industrialization and its consequences were one of the major factors they had to deal with, but not major enough to totally transform how they tried to rule.

Then in 1870 we got the final institutional pieces needed to support global economic growth: the industrial research laboratory, the modern corporation, and full globalization. One gathered communities of engineering practice to supercharge economic growth. The other organized communities of competence to deploy the fruits of invention. With globalization, cheap ocean and rail transport that destroyed distance as a cost factor and allowed humans in enormous numbers to seek better lives, along with communications links that allowed us to talk across the world in real time. The coming of all three of these more or less at once was a truly mighty change, rationalizing and routinizing the discovery and development and the development and deployment and not just the local but the global deployment and diffusion of technological advances.

To put it another way, the industrial research lab fused science to technological innovation and technology to enterprise: a scientist could science, an inventor could invent, and a technologist could technologize without one person having to be all three—plus financier, manager, chief pitchman, human resource department, and so forth. Division of labor. And the bureaucratic corporation allowed the visible hand of management to scale a successful workshop and store nationwide, or worldwide. And then there was diffusion: what one bureaucratic corporation could do, another could duplicate. And duplicate worldwide, with globalization. Discovery, development, deployment, and diffusion—the rationalization and routinization of those are what more than quadrupled the proportional rate of technological progress in the years around 1870.

The coming of all these three more than quadrupled the pace at which humanity’s technological empire was increasing. And that post-1870 step-up in the growth rate lasted. Thereafter it has been, for all politicians, hang on for dear life—and desperately try to rebuild working institutions on the fly as the socio-economic underpinnings of society are revolutionized and then re-revolutionized every single generation.

Stepping back and looking at the big picture, the post-1870 acceleration in growth and the more than twenty-fold amplification of human technological prowess in the years since 180 is a REALLY BIG F---ING DEAL. Briefly and very very roughly, what twenty workers were needed to do in 1870 with their eyes, fingers, thighs, brains, mouths, and ears, 1 worker was able to do in 2010. To get an equivalent proportional jump in the other direction, you have to go back from 1870 to the Bronze Age—to the year -2000 or so. We are, proportionately, as separate in technology from the railroad's Golden Spike and the first transoceanic cables of 1880 as those were from the earliest chariots and the sculptor of the dancing girl of Mohenjo-Daro:

Moreover, the overwhelming bulk of the potential benefits for humans from that twenty-fold -6000 to 1870 upward creep of technological knowledge had been eaten up by growing resource scarcity: the land and other natural resources available to support 1 person in -6000 had to support 200 by 1870. Thus better technology did not lead to as much changes in the life of the average peasant, craftsman, or servant as one would think. And so the problems of and techniques for ruling Russia faced by Czar Aleksándr II Nikoláyevich Romanov in the year 1870 still bore a family resemblance to those faced by Ensi Gilgamesh, son of Lugulbanda, in Uruk in the year -3000.

Few people know or consider the extent to which, back even in 1870, for the working classes of even the richest countries in the world, sheer calories were a considerable constraint on your daily activities. You could work and do stuff until you had drained your energy budget and so were tired. Then you more or less had to stop. That the work or other stuff you could do was tightly constrained because you simply could not afford the calories that you needed to do it—that is not a thing in the global north today. Yet that was an important part of the experience of humanity back before 1870.

But thereafter much was different. As much economic change and creative destruction as had taken place over 1720-1870 took place every 33 years after 1870. And the pace of change over 1720-1870 had already been more than fast enough to shake societies and polities to pieces. "All that is solid melts into air", Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx had written in 1848: all established hierarchies and orders are steamed away. But even they had no real idea what was coming after 1870. For Freddie from Barmen and Charlie from Trier mistook dawn for high noon. Yes, the business class—the French term bourgeoisie was the word they ultimately settled on (they had, earlier, followed Heinrich Heine is using the unfortunate terms “Jews and the Jew-like”)—had done revolutionary things in the century before 1848. But polities and societies had, for the most part, creaked and groaned, but had not (yet) shattered.

The post-1870 faster-pace repeated economic creative destruction upended societies, and in addition to opportunities posed two problems for governments: How were they to deal with the "destructive" part of creative destruction as it upended the lives of their people? And how were they to deal with neighboring governments that decided to use enhanced technological powers for evil for destruction and oppression? At the sharp end, a government gone horribly wrong was a genocide-scale problem for the people under its boot, and for the people who were that government's neighbors. And so the long 20th century saw the worst tyrannies ever.

I think the best way into understanding the problems thus created by economic creative-destruction at the post-1870 is the path blazed by Karl Polanyi, who denounced this technological-advance market-economic project, in which humanity is made rich as a byproduct of profit-motivated economic agents responding to the price signals sent by the rich as a:

stark utopia… [that] could not exist for any length of time without annihilating the human and natural substance of society…. Society took measures to protect itself, but whatever measures it took impaired the self-regulation of the market, disorganized industrial life, and thus endangered society in yet another way. It was this dilemma which forced the development of the market system into a definite groove and finally disrupted the social organization based upon it…

Think of it: Your community and its associated land-use and sociability patterns ("land"), your occupations and its remuneration on a scale appropriate to your status and to your desert resulting from your applying yourself ("labor"), and the very stability of and your ability to be paid for performing your job at all (“finance”)—all of these melt into air if they do not satisfy some maximum-profitability-use-of-resources test (“fictitious commodities”) imposed by some rootless cosmopolite thousands of miles away. Furthermore, it is a maximum-profitability test that is applied, not a societal-wellbeing test The (competitive, externality-free, in-equilbrium) market system definitely and certainly maximizes something. But what it maximizes is not any idea of the well-being of society, but rather the wealth-weighted satisfaction of the rich.

No:’ ‘The market giveth, the market taketh away; blessed be the name of the market' was not a stable principle around which a government could organize society and political economy. The only stable principle had to be some version of 'The market was made for man, not man for the market'.

So society responded: people believe that they have other rights rather than property rights (which are valuable only if your particular piece of property is useful for producing things for which the rich have a serious jones). And so they strove to organize society to vindicate those other Polanyian rights. And so society did so by attacking the market, and by attacking all of those it saw as its internal and external enemies that the global market system was empowering to oppress them. And those enemies included their government, that was trying and failing to manage the process to everyone’s satisfaction. Upheaval was inevitable. Revolution nearly so.

In addition, there was nationalism. For nationalism, let me give the mic to the very sharp Cosma Shalizi, channeling the even sharper Ernest Gellner:

Cosma Shalizi: Ernest Gellner, Nations & Nationalism: ‘The inhabitants of… “Agraria” were economically static and internally culturally diverse…. Because industrial economies continually make and put into practice technical and organizational innovations… their occupational structures change significantly in a generation…. No one can expect to follow in the family profession…. Training must be much more explicit, be couched in a far more universal idiom, and emphasize understanding and manipulating nearly context-free symbols…. It must in short take on the characteristics formerly associated with the literate High Cultures of Agraria…. States become the protectors of High Cultures, of “idioms”; nationalism is the demand that each state succor and contain one and only one nation, one idiom…. Faced with a difference between one’s own idiom and that needed for success, people either acquire the latter, or see that their children do (assimilation); force their own idiom into prominence (successful nationalism); or fester....

To recap: industrialism demands a homogeneous High Culture; a homogeneous High Culture demands an educational system; an educational system demands a state which protects it; and the demand for such a state is nationalism. The theory is coherent, simple, widely applicable, convincing, and empirically testable (which tests, to all appearances, it passes).….

It is hard to decide whether nationalists or anti-nationalists will find Nations and Nationalism more disturbing; rootless cosmopolitan though I am, it changed my mind on a great many subjects. This is already a rare enough achievement for a philosopher or social scientist…. Unfortunately for those of us not enamoured of nationalism, he wasn’t talking rubbish at all…

Thus it is very comprehensible the pseudo-classical semi-liberal order governments tried to build on the fly in the mid- and late-1800s, in what was retrospectively called the Belle Époque, fell apart into so many different catastrophes. Governments and élites failed to manage economic creative-destruction at the fever-heat pace at which it lurched forward after 1870, This failure-to-manage led to many, many societal reactions against the ongoing rush of claims that all was OK, and turned Europe into a hellhole and an abattoir until 1945.

One Metaverse Resource:

Pompeii: <https://digitalmapsoftheancientworld.com/digital-maps/roman-cities/pompeii/>

One Image:

Very Briefly Noted:

Martha J. Bailey <http://www.econ.ucla.edu/bailey/CV_Bailey.pdf>

Friedrich Engels: On Free Trade <https://www.panarchy.org/engels/freetrade.html>

Tressie McMillan Cottom: What the Reversal of Roe Means for Women’s Work <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/28/opinion/citizens-no-more.html>

Noah Gray & Zachary Cohen: Accounts of Trump Angrily Demanding to Go to Capitol on January 6 Circulated in Secret Service Over Past Year <https://www.cnn.com/2022/07/01/politics/secret-service-lunging-incident/index.html>

Wikipedia: Brenner Debate: ‘Agrarian Class Structure & Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe" <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brenner_debate>

Katie Paul: Exclusive: Meta Slashes Hiring Plans, Girds for ‘Fierce’ Headwinds <https://www.reuters.com/technology/exclusive-meta-girds-fierce-headwinds-slower-growth-second-half-memo-2022-06-30/>

Frances Coppola: Coppola Comment <https://www.coppolacomment.com/>

Michael Kimmelman: How Houston Moved 25,000 People From the Streets Into Homes of Their Own <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/14/headway/houston-homeless-people.html>

Annie Lowrey: Adam Tooze, Crisis Historian, Has Some Bad News for Us

Friedrich Engels (1888): On the Question of Free Trade <https://www.panarchy.org/engels/freetrade.html>

Ellora Derenoncourt & al.: The US Racial Wealth Gap, 1860–2020 <https://voxeu.org/article/us-racial-wealth-gap-1860-2020>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

Noah Millman: Legislative Dereliction of Duty: ‘The Court cannot force the legislature…. It can only say “no.” And in saying “no” it is rebuking another branch—the Executive—for doing precisely what they themselves are doing: innovating in response to the dereliction of duty by the legislature…

Eoin Higgins: Come On, Man: ‘During the 2020 Democratic primary, Joe Biden told voters that as president, he’d get Republicans in line. A year-and-a-half out from his inauguration, it’s clear that hasn’t happened. He’s not up to the challenge…

Matthew C. Klein: Most Americans Are Doing Well. For Now

Director’s Cut PAID SUBSCRIBER ONLY Content Below:

Paragraphs:

Again: the economic-policy problems we have are SOOOOOOO much smaller than if we were doing a repeat of the post-2010 ænemic recovery from the Great Recession:

Matthew C. Klein: Most Americans Are Doing Well. For Now: ‘The typical U.S. household earned more than ever as of May—even after accounting for inflation. And their finances were secure, with consumer spending rising at a steady clip even as their saving rate remained elevated. This is being obscured by the misfortunes of America’s investors…. The disconnect between the wellbeing of the vast majority and the discomfort of the few makes it challenging to interpret the aggregate data…. The virus knocked things off course, and there was good reason to fear that the damage would be permanent, as is often the case. Remarkably, that’s not what happened this time. By March 2021, real consumer spending had largely returned to the pre-pandemic trend. Americans haven’t yet made up for the ~$1 trillion in spending that they missed out on, but they are doing far better than they did after the global financial crisis…

LINK:

Yes, yes, yes. Ten thousand times yes!:

Michael Kimmelman: How Houston Moved 25,000 People From the Streets Into Homes of Their Own: ‘They’ve gone all in on “housing first,” a practice, supported by decades of research, that moves the most vulnerable people straight from the streets into apartments, not into shelters, and without first requiring them to wean themselves off drugs or complete a 12-step program or find God or a job. There are addiction recovery and religious conversion programs that succeed in getting people off the street. But housing first involves a different logic: When you’re drowning, it doesn’t help if your rescuer insists you learn to swim before returning you to shore. You can address your issues once you’re on land. Or not. Either way, you join the wider population of people battling demons behind closed doors…

LINK: <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/14/headway/houston-homeless-people.html>

Truly nice to see Adam getting more public-intellectual mindshare:

Annie Lowrey: Adam Tooze, Crisis Historian, Has Some Bad News for Us: ‘War, raising the specter of nuclear conflict. Climate change, threatening famine, flood, and fire. Inflation, forcing central banks to crush consumer demand. The pandemic, closing factories and overloading hospitals…. Not too long ago, Tooze was an obscure academic. Now he’s among the world’s most influential financial commentators, with loyal readerships in Washington, London, Paris, and Brussels, as well as on Wall Street… books, opinion pieces, and a podcast. But his greatest reach might come through his Substack newsletter, Chartbook, which comes across as a bloggy, ivory-tower version of the research notes that investment-bank analysts send to clients….

He writes for people who like reading material that “hits a bit heavier”: more technical than what you might read in the Financial Times, more intellectual than reports put out by Goldman Sachs. But it’s revelatory for many, including young lefties (described memorably in New York magazine as “Tooze Boys”), denizens of #econtwitter, history buffs, and money managers, many of whom trade on the data he digs up…. As Tooze sees it, the forces of central-bank tightening, war, inflation, and climate change are reinforcing one another. He is offering no reassurance about where that might head—only the hope that perhaps this polycrisis might be knowable to us…

Freddie from Barmen on the proper place of industrial policy. I do wonder what he would have done, and whether progress in neoclassical economic science would have been materially greater, had he been engaging with Walras, Jevons, and company rather than serving as the flame-keeper for the works of his old friend:

Friedrich Engels (1888): On the Question of Free Trade: ‘He gave me examples as to how much the Americans taxed themselves in order to enrich a few greedy ironmasters. “Well,” I replied, "I think there is another side to the question. You know that in coal, waterpower, iron, and other ores, cheap food, homegrown cotton, and other raw materials, America has resources and advantages unequalled by any European country; and that these resources cannot be fully developed except by America becoming a manufacturing country. You will admit, too, that nowadays a, great nation like the Americans’ cannot exist on agriculture alone; that would be tantamount to a condemnation to permanent barbarism and inferiority; no great nation can live, in our age, without manufactures of her own. Well, then, if America must become a manufacturing country, and if she has every chance of not only succeeding but even outstripping her rivals, there are two ways open to her: either to carry on for, let us say, 50 years under Free Trade an extremely expensive competitive war against English manufactures that have got nearly a hundred years start; or else to shut out, by protective duties, English manufactures for, say, 25 years, with the almost absolute certainty that at the end of the 25 years she will be able to hold her own in the open market of the world. Which of the two will be the cheapest and the shortest? That is the question. If you want to go from Glasgow to London, you take the parliamentary train at a penny a mile and travel at the rate of 12 miles an hour. But you do not; your time is too valuable, you take the express, pay twopence a mile and do 40 miles an hour. Very well, the Americans prefer to pay express fare and to go express speed.”

Really, really important. And really, really depressing:

Ellora Derenoncourt & al.: The US Racial Wealth Gap, 1860–2020: ‘A new long-run time series of the per capita wealth gap, from before the Civil War to 2020. A key finding is that severe racial differences in initial conditions after Emancipation have contributed greatly to today’s stalled progress…. Starting from a ratio of nearly 60 to 1 on the eve of the Civil War, the racial wealth gap has evolved in a ‘hockey-stick’ pattern, to a ratio of 10 to 1 by 1920 and 7 to 1 during the 1950s, where it has hovered since…. Three distinct channels of wealth convergence: (i) initial conditions right after the Civil War, (ii) savings-induced wealth accumulation, and (iii) capital gains…. Under equal conditions for wealth accumulation after slavery… the racial wealth gap should be around 3.1 today…. [But] saving rates (s) and capital gains (q) have been consistently lower for Black Americans…. Starting from the 1980s… racial income convergence has completely stalled… [and] capital gains on assets owned by white Americans have increased much more than those owned by Black Americans…

LINK: <https://voxeu.org/article/us-racial-wealth-gap-1860-2020>

Fed Overreaction: I'd suggest that Powell wonder aloud if further interest rate increases will be necessary in light of the success (his word) the Fed has had in bringing down expectations and a bemused puzzlement that the Treasury does not provide finer-grained instruments for gauging market sentiment.

Ancient Regime: I have ben impressed at how hard Louis worked to loose his head, how easily he could have accommodated the Generally Assembly. And he had the example of Charles II 'pour encourager les autres.'