READING: Fernand Braudel: "Efflorescences" in West Eurasia since -100

From "Civilization & Capitalism, 1500-1800: The Perspective of the World"

ernand Braudel: Civilization & Capitalism, 1500–1800: The Perspective of the World: “Efflorescences” in West Eurasia since –100: ’Alexandrian Egypt: My first example, an ancient but intriguing one, is Ptolemaic Egypt. Perhaps this looks too like chapter one in a school textbook - but steam had actually made its appearance in Alexandria between 100 and so BC, eighteen or nineteen-hundred years before Denis Papin or James Watt. Should one dismiss as of no account the invention by the ‘engineer’ Hero, of the aeolipile, a sort of steam-powered turbine - a mere toy, but one which nevertheless operated a mechanism capable of opening and shutting a heavy temple door some distance away?

This discovery followed in the wake of several others - the suction pump, the force pump, some early versions of the thermometer and the theodolite, various engines of war - more theoretical than practical admittedly - which depended on compressed or expelled air, or massive springs. In those distant days, Alexandria was a throbbing powerhouse of invention. Several revolutions had already taken place there during the preceding century or two - cultural, commercial and scientific: this was the age of Euclid, Ptolemy the astronomer and Eratosthenes; Dicaearchus, who seems to have lived in the city early in the third century BC, was the first geographer ‘to draw a line of latitude across a map, the line running from the Straits of Gibraltar along the Taurus and the Himalayas to the Pacific Ocean’.

A detailed study of the long Alexandrian episode would of course take us too far, through the extraordinary Hellenistic world resulting from Alexander’s conquests, in which territorial states like Egypt and Syria replaced the earlier model, the Greek city-state. It was a transformation which in some ways brings to mind the early development of modern Europe. And it tells us something we shall find frequently repeated: that inventions tend to come in clusters, groups or series, as if they all drew strength from each other, or rather as if certain societies provided simultaneous impetus for them all.

Brilliant though it was, the Alexandrian era eventually came to an end without its inventions giving rise to a revolution in industrial production (despite their being specifically directed towards technical application: Alexandria even had a school of engineering in the third century). No doubt the explanation lies largely in the existence of slavery, which provided the ancient world with the easily-exploited workforce it required. Thus in the East, the horizontal water-wheel remained a rudimentary mechanism adapted only to the heavy tasks of grinding grain, an everyday chore, while steam was used merely to operate ingenious toys, since, as a historian of technology has written, ‘no need was felt for a more powerful [source of energy] than those already known’, Hellenistic society remained indifferent to the inventions of its ‘engineers’

It might also be argued that the Roman conquest, coming as it did shortly after this age of invention, bears some responsibility. The economy and society of the Greeks had been open to the rest of the world for several centuries. Rome by contrast enclosed herself within the Mediterranean world; and by destroying Carthage, and subjugating Greece, Egypt and the East, Rome shut three doors leading to wider horizons. Would the history of the world (as Pascal suspected) have been different if Anthony and Cleopatra had won the battle of Actium in 31 BC? In other words, is an industrial revolution possible only at the heart of an open world-economy?

The earliest industrial revolution in Europe: horses and mills, from the eleventh to the thirteenth century: In the first volume of this book, I dwelt at some length on the changes of this period - in the use of horses, the horse-collar (an invention from eastern Europe which increased the animal’s traction power); oats (which Edward Fox has argued brought the centre of gravity of Europe back to the great rainswept cereal-growing plains of the north, in the days of Charlemagne and heavy cavalry); and triennial crop rotation, which was quite an agricultural revolution in itself.

I also referred to water-mills and windmills, the latter new inventions, the former a revival. I can therefore afford to be brief on this subject, about which information is now increasingly available, especially since many studies of this ‘first’ industrial revolution have been written, including Jean Gimpel’s lively and intelligent book, Guy Bois’s vigorous and provocative study, and M. Carus-Wilson’s classic 1941 article, which revived, and gave wide currency to the term “the first industrial revolution” to describe the widespread adoption in England of fulling-mills (about 190 between the twelfth and the thirteenth centuries) and sawmills, paper-mills, grinding-mills, etc. “The mechanising of fulling in the Middle Ages’, E.M. Carus-Wilson writes, ”was as decisive an event as the mechanisation of spinning and weaving in the eighteenth century."

The large wooden paddles turned by a water-wheel and introduced to the major industry of the time - woollen cloth - to replace the feet of the fulling-workers, proved to be the instruments of a revolutionary upheaval. Most water courses near the towns, which were generally in the lowlands, did not have the motive force of the upland streams and waterfalls. Fulling-mills therefore tended to be sited in less populated areas, to which they attracted their merchant clientèle. The hitherto jealously guarded craft monopoly of the towns was thus by-passed. The towns inevitably tried to defend themselves by forbidding weavers working within the walls to have their cloth fulled outside. The authorities in Bristol in I346 forbade "any man to take outside this city for fulling any kind of the cloth known as raicloth on pain of losing xi d. per cloth‘. That did not prevent the "mill revolution’ from taking its course, both in England and throughout the continent of Europe which certainly did not lag behind on this occasion.

But the point is that this revolution took place alongside a number of other revolutions: a significant agricultural revolution which pitted large numbers of peasants against forest, marsh, seashore and river, and encouraged the adoption of triennial rotation; and a simultaneous urban revolution prompted by demographic expansion - never before had towns sprung up so thickly within such easy reach of one another. A clear distinction of functions, a ‘division of labour’ between town and countryside, sometimes brutally felt, became the norm. The towns took over industrial activity, became the motors of accumulation and growth, and re-invented money. Trade and traffic increased. With the Champagne fairs, the new economic order of western Europe became first discernible then clearly visible. In the Mediterranean, shipping and overland routes, especially to the east were gradually reconquered by the Italian cities. The whole economic area was undergoing the expansion without which no growth would be possible.

The word growth, in the sense of overall development is indeed unhesitatingly used in this context by Frederic C. Lane. In his view, we can undoubtedly talk of a period of ‘sustained growth’ in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries in, say, Florence or Venice. How could it be otherwise at a time when Italy was the very centre of the world-economy? Wilhelm Abel even maintains that the whole of western Europe was caught up in a wave of general development from the tenth to the fourteenth century, citing as evidence the fact that wages rose faster than cereal prices.

The thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries [he writes] witnessed the first industrialization of Europe. At this time, the towns with all their commercial and craft activities were undergoing vigorous development, less perhaps because of the technical advances of the age (though these were not negligible) than as a result of the generalization of the division of labour, thanks to which work yields were increased, and it was probably this higher productivity which made it possible not only to resolve the difficult problem of providing a growing population with its essential food supplies, but even to feed it better than ever before. The only analogous occasion was during the ‘second indus- trialization’ in the nineteenth century - admittedly on a very different scale.

In other words, the eleventh century saw the beginning of what was effectively a period of ‘sustained growth’ on the modern pattern, one which would not recur before the English industrial revolution. It is hardly surprising that the ‘global development’ theory seems the logical explanation. A whole series of inter-related advances were taking place in production and productivity, in agriculture, industry and commerce, as the market expanded. During this first serious awakening of Europe, there was even expansion in the ‘tertiary’ sector (another sign of development) with a rise in the number of lawyers, notaries, doctors and university professors.

We actually have some statistics about the notaries: in Milan in 1288, there were 1500 for a population of about 60,000; in Bologna, 1059 for a population of 50,000; in Verona in 1268 there were 495 for 40,000; in Florence in 1338, there were 500 for a population of 90,000 (but Florence was a special case: business was so well organized there that bookkeeping methods often rendered the services of a notary unnecessary). And predictably, with the fourteenth-century recession, the number of notaries declined comparatively; although it climbed again in the eighteenth century it never again reached the heights attained in the thirteenth - no doubt because the abnormal rise in the number of notaries in medieval days was created both by the increase in economic activity and by the need for the services of clerks when the vast majority of people were illiterate.

Europe’s great leap forward ended in the monster recession of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (roughly from 1350–1450) following the Black Death which may have been as much consequence as cause - the slowing-down of the economy, dating from the cereal crisis and famine of 13I5–17, preceded the epidemic and may have rendered its sinister work easier. So plague was not the only grim reaper of the prosperity of a previous age: this was already slowing down if not at a standstill by the time the disaster struck.

How then is one to explain Europe’s greatest triumph and greatest disaster before the eighteenth century? Most probably by the dimensions of a demographic explosion with which agricultural production found it impossible to keep pace. Falling yields are the mark of any agriculture pushed beyond the bounds of its productive capacity, when it does not possess the methods or techniques which might compensate for the rapid exhaustion of the land.

Guy Bois’s study, based on the example of eastern Normandy, analyses the social aspects of this phenomenon: the underlying crisis of feudalism which broke up the old partnership between the landlord and the peasant farmer. This destructured society, shorn of its code and vulnerable to disorder and random warfare, was in search both of a new equilibrium and a new code - results not attained until the establishment of the territorial state which would be the salvation of the seigniorial regime.

Other explanations could be suggested - in particular the fragility of the countries most affected by the energy revolution represented by the new mills: northern Europe from the Seine to the Zuyder Zee, from the Low Countries to the Thames valley. New territorial states like France and England, although by now strong political units, were not yet manageable economic units: they were to be seriously affected by the crisis. What was more, in the early years of the century, with the decline of the Champagne fairs, France, having been for a brief moment the centre of European trade now found herself excluded from the circuit of profitable trading links and the first capitalist successes. The cities of the Mediterranean were soon to take over from the new northern states, and this would mark the end, for the time being, of that supreme confidence visible in Roger Bacon’s extraordinary glorification of the machine:

Machines may be made by which the largest ships, with only one man steering them, will be moved faster than if they were filled with rowers; wagons may be built which will move with incredible speed and without the aid of beasts; flying machines can be constructed in which man may… beat the air with wings like a bird…. Machines will make it possible to go to the bottom of seas and rivers.

The age of Agricola and Leonardo da Vinci: a revolution in embryo: When after this long and painful crisis Europe began to revive again, a wave of renewed trade and vigorous growth ran along the axis linking the Netherlands and Italy, through the middle of Germany. And it was Germany, a secondary zone for trade, which led the way in industrial development: possibly because this was one way of breaking into international exchange, situated as Germany was between the two dominant poles, to the north and south.

But it was above all because of the development of mining. The early revival of the German economy in the 1470s, ahead of the rest of Europe, was not the only result. The extraction of metallic ores - gold, silver, copper, tin, cobalt and iron - stimulated a whole series of innovations (the use of lead to separate out silver from copper ore for instance) as well as the creation of machinery, on a gigantic scale for the time, to pump out water from the mines and to bring up the ore. The engravings in Agricola’s book provide an impressive picture of the sophisticated technology developed at this time.

It is tempting to see these achievements, which were imitated in England, as the real forerunners of the industrial revolution. The expansion of mining did indeed have repercussions in every sector of the German economy of the time in fustians, wool, the leather trade, various kinds of metallurgy, tin, wire, paper, the new arms industry and so on. Trade stimulated large-scale credit networks and big international firms like the Magna Societas were established. The urban crafts flourished: there were 42 craft guilds in Cologne in 1496; 50 in Lübeck; 28 in Frankfurt-am-Main. Transport was improved and modernized; large firms began to specialize in carrying goods. And Venice, the queen of the Levant trade, established close trading relations with High Germany, since she needed silver.

The German cities unquestionably offered for over half a century the spectacle of a rapidly-expanding economy in virtually every sector. But everything began to slow down or stop in the years around 1535 when, as John Nef’s work has shown, silver from America started to compete with the output of the German mines; at about the same time, 1550, Antwerp’s commercial supremacy was also being challenged. Was it not a source of inferiority for the German economy to be dependent on external powers, to have been manufactured to meet the needs of the two real centres of the European economy, Venice and Antwerp? The age of the Fuggers, when all is said and done, was the age of Antwerp.

Even more outstanding success was achieved in Italy, at about the time when Francesco Sforza came to power in Milan in I450. It was outstanding, partly because it had been preceded by a series of exemplary revolutions. The first of these was a demographic revolution which continued until mid-sixteenth century. The second was the appearance in the early fifteenth century of the first territorial states, still small in size, but already modern in structure: it even seemed for a brief moment that Italian unity was in the air. And lastly, an agricultural revolution along capitalist lines was taking place among the canals of the great Lombardy plains. All this in a climate of scientific and technical discovery: this was the age when hundreds of Italians, sharing the enthusiasm of Leonardo da Vinci, were filling their notebooks with designs for extraordinary machines.

Milan now entered upon a singular phase in its history. Having been spared during the terrible crisis of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (precisely because of its agricultural productivity, according to Zangheri), the city witnessed a remarkable spurt of manufacturing activity. Woollens, cloth of gold and silver, and armour began to take the place of the fustians which had been Milan’s staple industry in the early fourteenth century. The Lombard capital was caught up in a huge wave of commercial activity linking it to the fairs of Geneva and Chalon-sur-Saône, to cities like Dijon and Paris, and to the Netherlands.

At about the same time, the Milanese capitalists were completing their takeover of the countryside, with the reorganization of properties into large estates, the development of irrigated meadows and livestock farming, the digging of canals both for irrigation and transport, the introduction of rice as a new crop, and even in many cases the disappearance of fallow land, with continuous rotation of cereals and forage crops. It was in fact in Lombardy that ‘high farming’ - later to be developed in the Netherlands and transferred with celebrated results to England, first saw the light.

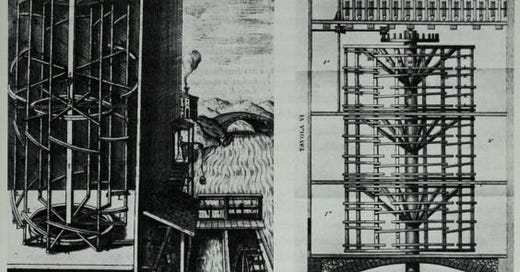

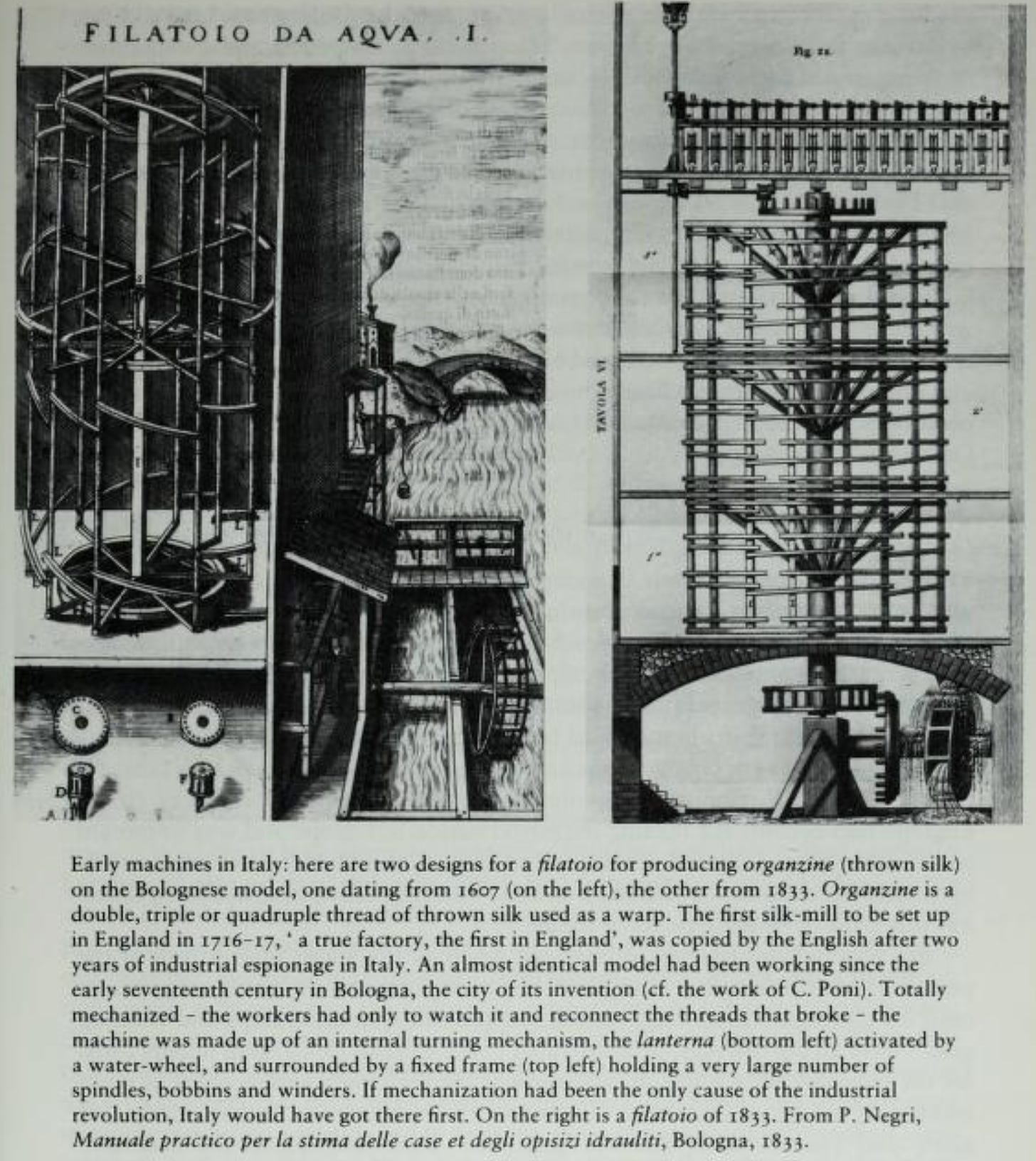

Hence the question put by our informant and guide Renato Zangheri: why did this substantial transformation of both the industry and the countryside of Milan and Lombardy come to nothing? Why did it not lead to an industrial revolution? Neither the infant technology of the time nor the lack of energy supplies seems an adequate explanation. "The English industrial revolution was not based on any scientific or technical progress not already available in the sixteenth century.: Carlo Poni was astonished to discover the sophistication of the hydraulic machines used in Italy to throw, spin and mill silk, with several mechanical processes and rows of spindles all turned by a single water-wheeel.

Lynn White has argued that even before Leonardo da Vinci, Europe had already invented the whole range of mechanical devices which would actually be developed during the next four hundred years, that is until electrical energy, as and when the need was felt for them.** As he puts it: ‘a new device merely opens a door; it does not compel anyone to enter’. Quite so. But why did the exceptional conditions which were combined in fifteenth-century Milan fail to create any such need or demand? Why did the Milanese revolution crumble instead of thrive?

The available historical data does not really provide enough evidence to answer this question. We are reduced to conjecture. In the first place, Milan did not have access to any large national market. And the profits from land did not outlast the first wave of speculation. The prosperity of the first industrial entrepreneurs, if we are to believe Gino Barbieri and Gemma Miani, was only on a small scale, creating a sort of modest capitalist class.

But how strong an argument is that? After all, the first cotton magnates often had very humble beginnings. Was it not rather Milan’s misfortune to be so close to Venice, yet so far from sharing Venice’s dominant position? And not to be a port, with access to the Mediterranean and the international export trade, free to experiment and take risks? Is the failure of Milan’s ‘industrial revolution’ perhaps proof that an industrial revolution, as a total phenomenon, cannot be built up entirely from within, simply by the harmonious development of the various sectors of the economy; that it must also be based on command of external markets - the sine qua non of success? In the fifteenth century, as we have seen, this commanding position was occupied by Venice, and to some extent (for Spanish trade) by Genoa.

John U. Nef and the first British industrial revolution, 1560–1640: The industrial expansion which took place in England between 1540 and 1640 was much more clear-cut and thorough-going than the early experiences either of Italy or Germany. In mid-sixteenth century, the British Isles were still, industrially speaking, far behind Italy, Spain and the Netherlands, Germany and France. A hundred years later, the situation had been miraculously reversed and the speed of the transformation had been so fast that there is no parallel before the equivalent wave of change in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, in other words, the industrial revolution.

By the eve of the Civil War (1642) England had become the leading industrial nation in Europe and was to remain so. It is this ‘first industrial revolution’ to which John U. Nef drew attention in his article which caused a sensation when it was originally published in 1934 and has lost none of its analytic force today.

But why did this happen in England, when all the major innovations of the period - I am thinking for example of the blast furnaces, the various apparatus used for underground mining: tunnels, ventilation systems, pumps and winding gear - were all borrowings, demonstrated to the English by German miners hired for the purpose? Why England, when it was the craftsmen and workers of more technically advanced countries - Germany, the Netherlands, but also Italy (for glass) and France (wool and silk textiles) - who contributed the necessary techniques and skills for the establishment of a series of industries quite new to Britain - paper-mills, powder-mills, glass, mirrors, cannon-founding, alum and copperas (green vitriol), sugar refining, saltpetre, and so on? The remarkable thing is that when these industries did arrive, England should have developed them on a scale hitherto unknown: the growing size of firms, the dimensions of the buildings, the rising numbers of workers, soon running into tens or even hundreds, the comparatively high level of investment which was reaching thousands of pounds, whereas the annual wage of a worker was only about £5 - all these were completely new and indicate how extraordinary was the expansion of English industry in this period.

On the other hand, the decisive feature of this revolution - a completely home-grown one so to speak - was the increasing dependence on coal, which had become a major element in the English economy. Not as it happened by deliberate choice, but in order to meet a visible deficiency. Wood had become increasingly scarce in England and was costing high prices by mid-sixteenth century; scarcity and expense dictated the move to coal. Similarly, the sluggish flow of most English rivers, which had to be raised by dams and diverted by canals to work overshot wheels, made hydraulic energy much more expensive here than in continental Europe and would eventually provide an incentive to research into the power of steam, or so John Nef suggests.

So England, unlike France or the Netherlands, went in for coal-mining on a grand scale, beginning with the Newcastle coalfields and the many local seams. Mines which had previously been worked open-cast by a part-time rural labour force now began to operate continuously; pits were dug up to 40 or 100 metres deep. From about 35,000 tons in 1560, output had risen to 200,000 tons by the beginning of the seventeenth century. Wagons running on rails carried the coal from the pithead to the docks: specialized ships, in ever-increasing numbers were taking it all over England and even to Europe, by the end of the century. Coal was already being regarded as a form of national wealth:

England’s a perfect world, hath Indies too,

Correct your maps, Newcastle is Peru

as an English poet put it in 1650. The replacement of charcoal by coal not only made it possible to heat domestic interiors - bringing a sinister pall of smoke to London; it also affected industry which had however to learn to adapt to the new fuel and devise new expedients, in particular to protect the matter being processed from the sulphurous fumes of the burning coals. One way and another, coal was introduced to glassmaking, to breweries, brick-works, alum manufacture, sugar refineries and the industrial evaporation of sea-salt. In every case, this meant a concentration of the workforce and inevitably of capital. Manufacturing industry was born; with it came the great workshops and their alarming din which sometimes proceeded uninterrupted day and night, and their throngs of workers who, in a world used to artisans, were remarkable both for their large numbers and as a rule for their lack of skill.

One of the farmers of the ‘alum houses’ built during the reign of James I on the Yorkshire coast and each employing about sixty workers, explained in 1619 that the manufacture of alum was a ‘distracted worke in severall places, and of sundry partes not possible to bee performed by anie one man nor by a fewe. But by a multitude of the baser sort of whom the most part are idle, careless and false in their labour’.

Technically then, with larger factories and the widespread use of coal, England was certainly innovating in the industrial sector. But what really gave the impetus to industry and probably to innovation as well, was the substantial enlargement of the domestic market, for two complementary reasons. The first was rapid population growth - estimated at 60% in the course of the sixteenth century. At the same time there was a large rise in agricultural incomes, which turned many peasants into consumers of industrial products. To meet demand from the growing population and especially from the visibly-expanding towns, agricultural output was increased in several ways - by the reclamation of land, by enclosures at the expense of commons and grazing, by crop specialization but without any truly revolutionary measures to increase productivity or the fertility of the soil. These would only begin to appear after 1640 and then only very gradually until 1690.

Agricultural output thus began to lag somewhat behind demographic expansion as is proved by an agricultural price rise much greater overall than the industrial price rise. The result was a visible increase in prosperity in the countryside. This was the age of the ‘great rebuilding’ as rural dwellings were restored, improved and enlarged, as upper storeys replaced attics, windows were glazed, chimneys were built for burning domestic coal. Inventories compiled after death tell us of a new-found affluence reflected in furniture, linen, hangings, pewter vessels. This domestic demand undoubtedly stimulated industry, trade and imports.

Promising though it appeared, this lively burst of industrialization did not carry all before it. Some important sectors continued to lag behind. In metallurgy for instance, the blast furnace on the modern German model, a heavy user of fuel, by no means ousted all the bloomeries, old-fashioned furnaces some of which were still in operation in 1650 - and in any case even the blast furnaces continued to burn charcoal. Only in 1709 did the first coke-fuelled blast furnace appear - and this remained unique of its kind for another forty years.

Several explanations have been suggested for this by T. S. Ashton and others, but Charles Hyde’s conclusion in his recent book seems to me to be irrefutable: if coke only replaced charcoal in about 1750, it was simply because until then production costs favoured the latter. What was more, even after the adoption of coke, English metallurgy long remained inferior, both in quality and quantity to that of Russia, Sweden or France. And while light metal industries (cutlery, nail-making, tools, etc.) grew steadily from mid-sixteenth century, they were using imported Swedish steel.

Another backward sector was the cloth industry, now faced with a long crisis in foreign demand which made it necessary to undergo some painful adjustments while output remained virtually stationary from 1560 to the end of the seven- tenth century. Still largely a rural cottage industry, cloth production was increasingly brought within the putting-out system. Whereas in the sixteenth century this industry alone had been responsible for 90% of English exports, and the figure was still 75% in 1660, by the end of the century it had fallen to only 50%.

But these problems cannot explain the stagnation that set in in England after the 1640s: while the economy did not decline, neither did it progress. The population had stopped rising, agriculture was producing more and better quality crops; it was investing for the future - but rural incomes had fallen with prices; industry was ticking over but no longer innovating, at least not until 1680 or so. If this standstill had been confined to England, one might perhaps have put it down to the effects of the Civil War which began in 1642 and brought considerable disruption; or one could point to the still inadequate nature of the national market, or England’s comparatively poor position in the European world-economy, in which Holland was still the dominant economic power. But England was by no means alone in this experience - one that was undoubtedly shared by all the north European countries which had been progressing alongside her and were now simultaneously retreating. The “seventeenth-century crisis” might strike at different times, but it left its mark everywhere.

To return to England however, John U. Nef’s own diagnosis is that while the industrial advance certainly slowed down there after 1642, it did not collapse; there was no slipping backward either. What may in fact have happened, and we shall return to this point apropos E. L. Jones’s analysis, was that the seventeenth-century crisis, like all periods of demographic slowdown, brought some increase in per capita incomes and a transformation of agriculture, which had repercussions on industry too. By taking Nef’s arguments further, we might say that the English industrial revolution of the eighteenth century had already begun in the sixteenth and was simply making progress by stages. It is an explanation from which some lessons may be drawn.

But could not the same be said of the whole of Europe, where since at least the eleventh century, a series of linked and in a sense cumulative transformations had been experienced? Every region in turn sooner or later underwent a burst of pre-industrial growth, with the accompanying features one could expect, particularly in agriculture. Industrialization was in a sense endemic throughout the continent. Outstanding and important as Britain’s role was in this story, Britain was by no means the sole initiator and inventor of the industrial revolution accomplished on her soil.

This explains why that revolution had scarcely appeared, let alone achieved its decisive successes, before it was spreading unopposed to nearby Europe, where it scored a series of comparatively easy triumphs, encountering none of the obstacles which so many under-developed countries have met in the twentieth century…

LINK: <https://archive.org/details/civilizationcapi03brau/page/557/mode/1up?view=theater>

Wow, that was great. I've always been fond of Braudel. I find his materialism refreshing.

One invention from the 13th century revolution not mentioned, the chimney fireplace with its ability to create a draft and produce hotter and more efficient fires. This benefited northern Europe in a lot of ways. Just being able to keep warm and cook with less wood is revolutionary. Even now one runs into articles on technologies to get third world people a better way to cook than using an open wood or dung fire.

If you've done work in industrial intelligence, you develop a sense that inventions are only meaningful in an ecology. Wheels are only useful if you have roads, a relatively gentle topography, draft animals and a need to travel places without good water routes. It's like a game of Tetris. It is nearly impossible to build a tall, skinny tower. One has to fill in the layers one by one. Our technology base is broad and deep. I once took a course where we discussed why the ancient Romans couldn't make integrated circuits circa 1971, so we didn't need to imagine Romans firing lasers at molten tin droplets. Still, we had a lot to discuss.

Edison's breakthrough wasn't the light bulb, it was the electrical utility and house wiring. Morse's breakthrough wasn't his code or the telegraph, but an insulated wire suitable for use outdoors. Tesla's breakthrough wasn't his electric car. It was his network of charging stations. He even gave early adopters free charging like Straus subsidizing pasteurized milk to encourage its adoption.

It's one thing to build a simple steam engine to open a heavy door. That's a one shot demo. If you wanted to adopt steam powered doors for ordinary use, you'd run into issues of energy efficiency, standby power, control and safety and architectural modifications. Then there's the why would one want such a thing. Mines in the ancient world rarely ran deep. It is only when one has developed deep rock mining technology that the issue of pumping water out of deep mines emerges. There has to be an ecology with push and pull.

O-Ring theory sounds interesting. It's not the only theory that deals with the benefits of concentrated skills. Didn't you point out a paper some time ago describing the innovative benefits of urbanization in that it allows skills to aggregate as cities encourage communication between skilled people? I wonder what O-Ring theory says about subcontracting important components of one's business to other companies since the corporate barrier prevents skill levels from concentrating.

Skill concentration seems to have pre-economic roots. There was recently an article in Science about how "Selective cultural processes generate adaptive heuristics" which looks at the way skills are transmitted. I love one particular line, re: Micronesian navigational skills, "Few aspirants, however, succeeded in being initiated as masters because some of the most important skills were nonintuitive, difficult to learn, and unforgiving of mediocrity ...."