First Republic Falls, & What Happens to Banking Next

Not a big crisis, but also not a terribly well-handled one—and that is worrisome; not well-handled because there are no great options, or because people are not walking down the garden of forking p...

There is the Bob Rubin question: What will we wish in the future that we had done at this meeting? I do not think regulators have been asking that question with as much urgency as they should this spring. Walking down the garden of forking paths one month, three months, one year, five years, and twenty years, and then looking back—that is what you need to do.

At the end of April the market value of First Republic’s equity was $2 billion. Now it is gone.

Now JP Morgan Chase has paid the FDIC $10 billion for First Republic in return for a number of guarantees and support mechanisms. JPMC has gotten a $10 billion market valuation pop from this transaction. Simple Modigliani-Miller—the assets minus the liabilities are the assets minus the liabilities no matter who holds them, or how the cash flows from them are carved up—would suggest that, had the Treasury, the Fed, and the FDIC offered the old First Republic management and shareholders the same support it offered JPMC, First Republic would now look like a healthy bank, with a share price not at the end-of-April $3.50 a share but rather $35 a share.

And had the Treasury, the Fed, and the FDIC done that:

JPMC would now be slightly less dominant,

banking-sector concentration and consolidation would be slightly lower,

a regional bank with at least some socially valuable knowledge and network capital would still be around,

other regional banks would be able to raise equity capital, which now they cannot do out of fear that if the bank comes close to hitting the wall they will be zeroed out,

confidence in the banking system—confidence that your banking relationship is not going to be upended some weekend and you will wind up dealing with a different group of people—would be greater, and

the fear that the FDIC, Fed, and Treasury might have limits in the support they will provide to keep everything having to do with accounts used for operational payments from hiccuping—that fear would be further away.

On the other side, if the government had provided support to keep First Republic in business as a going concern:

No bankers would have been obviously and publicly punished,

The rescue might not have stuck—our banking system has multiple expectational equilibria in the absence of full deposit insurance and full confidence in the system, and First Republic’s deposits might have taken another downward lurch, and

Jim Millstein and company believed that keeping First Republic in business was “inconsistent with the spirit of Dodd-Frank”:

Brooke Masters & al.: JPMorgan: the bank that never lets a crisis go to waste: ’The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, advised by… Jim Millstein… believed… financial engineering [to preserve an independent First Republic] would have required government assistance… inconsistent with the spirit of the Dodd-Frank…. Under a 1992 law, the FDIC must choose the solution that imposes the “least cost” on the deposit insurance fund…

To the last of these, my response is: “Huh?” Why was the deal offered to JPMC not also equally inconsistent with the spirit of Dodd-Frank? If someone could explicate this to me, I would be very grateful.

Now (1) and (2) may well be sufficient reasons for the FDIC, the Fed, and the Treasury to have chosen the path that they did. But it does mean that banks that have substantial mark-to-market duration-bet losses (notionally counterbalanced by the anticipated capital gain as they hold their bonds to maturity) cannot now raise the capital that they need to no longer be vulnerable to a social media-triggered deposit bank run. And it does mean that banks that have substantial commercial real-estate losses that are not yet fully public and have not yet been digested by the market also cannot now raise the capital that they need to no longer be vulnerable to a social media-triggered deposit bank run. So the banking crisis will roll forward, unless something stops it.

My hope for something to stop it was and is a letter—a letter from Chuck Schumer, Mitch McConnell, Hakeem Jeffries, and Kevin McCarthy stating that they understand that the increasing volatility of deposits has created a new vulnerability and problem for bank regulators, that they are fast-tracking legislation to provide a durable fix, and that in the meantime they are eager for regulators to do their job and keep the deposits of Americans safe. In other words, a letter to Jay, Janet, and Marty stating: “what these people have done was done by our will and for the good of the state”. But no such letter has appeared. And it does not seem likely that any such will appear.

So the slow-moving banking crisis will roll forward, as an industry that ought to be raising equity—its assets have taken a huge hit both from the Fed’s tilting of the intertemporal price structure via interest-rate increases and from losses in commercial real estate—is not able to do so.

Meanwhile, Jamie Dimon of J.P. Morgan Chase now bestrides Wall Street as a colossus greater relative to the market and the government than anyone since, well, since the original John Pierpont Morgan himself:

Jennifer Surane & Francine Lacqua: Jamie Dimon Says US Needs to ‘Finish’ the Bank Crisis: ‘Dimon has played a central role in the reaction to the industry’s worst period of tumult in more than a decade…. "We need to finish the bank crisis,’’ Dimon said. “Whatever the FDIC, the OCC, the Fed—whatever they need to do to make it better they should do.”… Banks should have been encouraged to look at a broader range of potential pitfalls, rather than one annual stress test that ran hundreds of thousands of pages, breeding a “false sense of security”…. Dimon said regulators need to get a better handle on smaller banks’ financial situations, to "not be surprised constantly…. I think there needs to be humility on the part of regulators. They should look at it and say, ‘OK, we were a little bit a part of the problem’ as opposed to just pointing fingers.‘’ Despite the upheaval, the regional-bank industry is “quite strong,” he said, and “hopefully we’re getting near the tail end” of the problem…

But why should we have such hope? As Matt Levine wrote on Tuesday the 9th about Silicon Valley Bank:

Matt Levine: It’s Never too Late for Banks to Hedge: ‘SVB thought that it was hedged… long-term bonds… fund[ed] with deposits….. Deposits are technically very short-term…. but it is traditional in banking to think… “deposit franchise” and… relationship between banker and customer would make customers unlikely to take their money out. If [SVB] had swapped the assets to short-term rates, and then rates fell, it would lose money…. SVB thought that was the bigger risk… got rid of… hedges… because it had become… worried that the hedges would hurt it if rates fell…. A mark-to-market, legalistic approach: A bank… [is] risky and fragile and particularly at risk from rising interest rates, which increase its cost of funding and decrease the value of its assets…. A traditional, relationship-driven approach: A bank has a “deposit franchise” of long-term loyal customers, which gives it long-term rate-insensitive funding to invest in long-term assets, and it is at risk from falling interest rates, which decrease the amount of net interest margin…. That’s the theory… but obviously things have not been working out…. The value of the deposit franchise evaporated overnight, leaving only a pile of financial assets that had lost value, funded by a bunch of short-term loans that came due…

And Matt also observes:

PacWest, Western Alliance Slide as Regional Bank Stocks Fall. Betting Against Banks Brings Reward and Backlash. Regional Banks Will Cut Bonuses While Big Firms Raise Incentive Pay. US lenders warned that commercial property is ‘next shoe to drop’…

Another member of the Matt Conspiracy, Matthew Klein, is somewhat flummoxed:

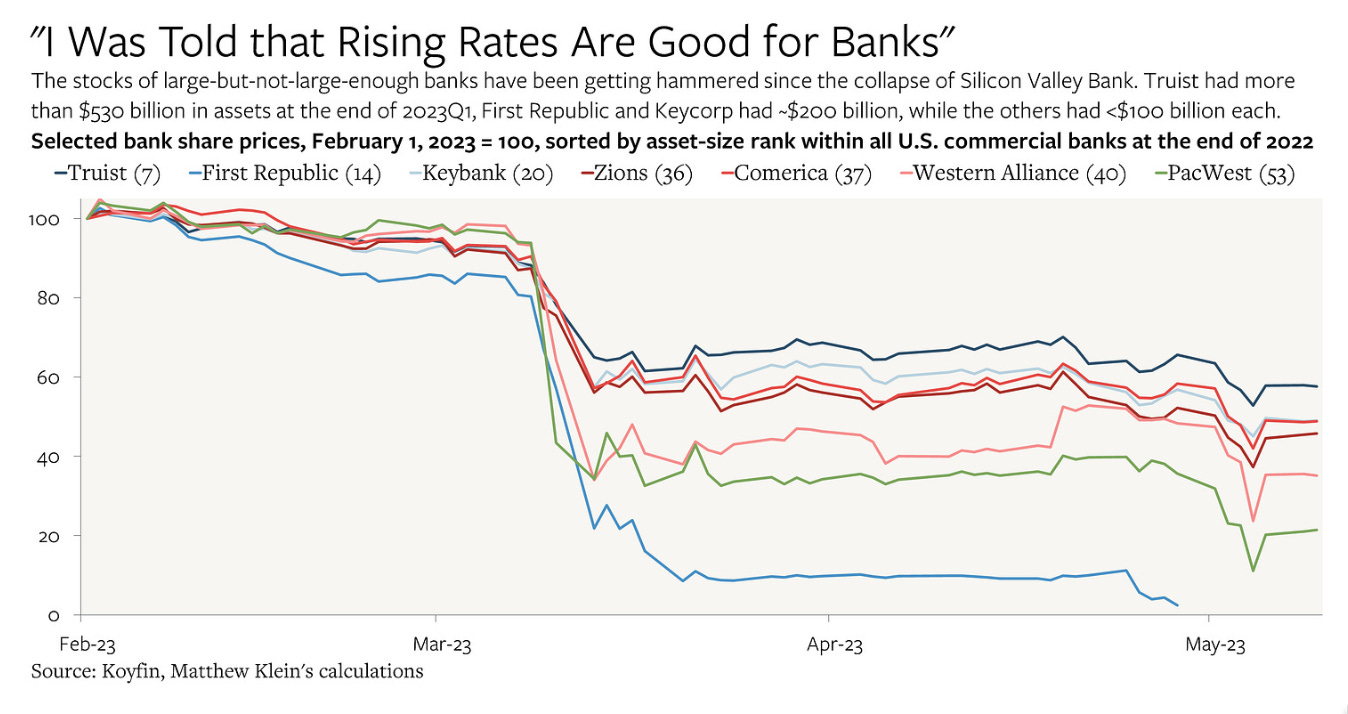

Matthew Klein: Banks Are Blowing Up While the Economy is Strong. Time to Worry?: ’My second child was born shortly after Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed.1Since then, First Republic Bank…. The share prices of other large-but-not-enormous banks, including Truist, Keycorp, Zions, Comerica, Western Alliance, and PacWest…. The survivors that remain under acute pressure include the 7th-largest U.S. commercial bank (Truist) and hold more than $1 trillion in assets among them…

And I am beginning to hear cries for “narrow banking”—for getting banks out of the business of accepting deposits to finance loans and into the business of accepting deposits to park them at the central bank. Who then finances loans? That is left hanging. Given that our financial system’s big problem, from my viewpoint, is that we do not mobilize enough of society’s risk-bearing capacity, eliminating banks’ ability to do idiosyncratic-risk elimination via the deposit-loans channel is potentially a major social loss. But many think otherwise. For example:

Martin Sandbu: : ’A new way to keep banking safe…. Paul Tucker… my colleague Laura Noonan’s interview… a new approach to preventing deposit runs…. Banks… should be required to pre-position collateral with central banks to cover 100 per cent of their demand deposits (the deposits that can be withdrawn without notice)…

I must say, these high deposit betas and inverse-Gamestop bank runs were not on my Bingo card for 2023 at all.

"our financial system’s big problem, from my viewpoint, is that we do not mobilize enough of society’s risk-bearing capacity, eliminating banks’ ability to do idiosyncratic-risk elimination via the deposit-loans channel is potentially a major social loss. But many think otherwise."

I wonder if that's quite right. My sense is that narrow banking advocates are aware of the social loss but are axiomatically committed to the position that market distortions are worse than any other harm; the social losses are like an unpleasant medicine that must be swallowed for the ultimate good of the patient. "Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate" etc.

I don't know whether narrow banking works out to a net gain in purely economic terms, but it occurs to me first, that there is such a thing as the theory of the second best, and second, that it is politically completely infeasible anyway. The modal American has no sense at all of the degree to which the American housing market is supported by socialist government intervention and doesn't want to learn. It's not just the mortgage interest deduction; the standard terms of an American mortgage - 30Y fixed rate term + refinance with no penalty - are surreal by international standards, and the reason for that is that they would never be offered by the private sector. So who is going to buy all that agency MBS if regional banks don't? The stated reason why narrow bankers don't care is that they think the mortgage market should be a purely private sector affair, but the real reason is that they don't have to bear the political consequences of this policy change. Which is to say that they should not be taken too seriously.

Open bank assistance is considered verboten since 1993, due to the requirement to not benefit shareholders. Agree that a new law could reverse that but SVB, Signature, and First Republic would always have been resolved under existing regulatory schema.