Discover more from Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality

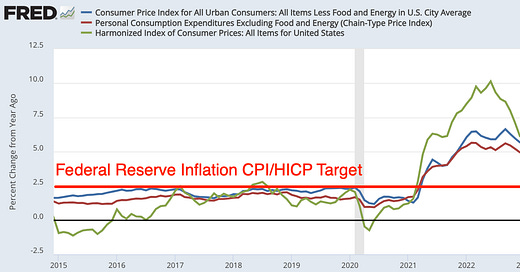

First: Six Episodes of U.S. Inflation Above 5%/Year in þe 1900s, &

BRIEFLY NOTED: For 2022-03-19 Sa

First: Six Episodes of U.S. Inflation Above 5%/Year in the 1900s

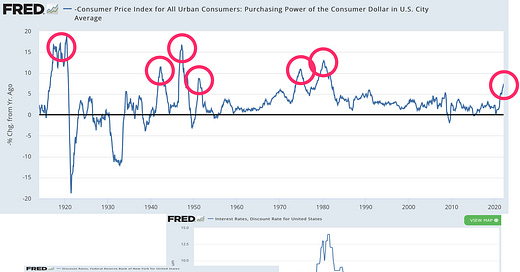

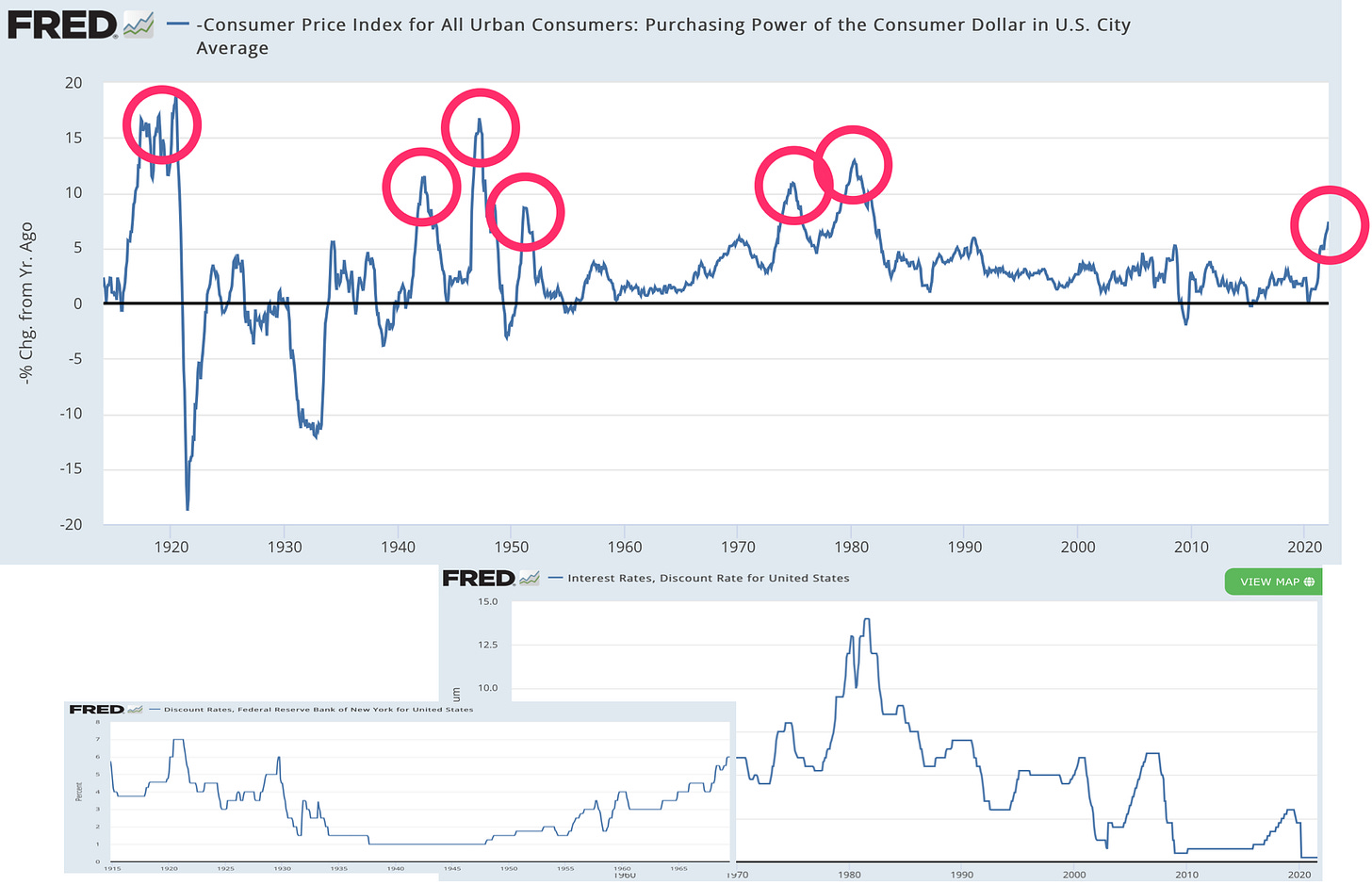

The top graph is the CPI inflation rate; the bottom graphs are overlapping graphs of the Federal Reserve’s discount rate—the rate at which it lends to banks on reasonable collateral.

Counting 1974 and 1979 as two episodes, there were six times in the twentieth century during which the annual inflation rate got above 5%. One was the World War II inflation—cut off by price controls. Then came the post-WWII structural-rebalancing-and-pent up demand inflation, and then the Korean War structural-rebalancing inflation as the U.S. government wheeled its economy to fight the Cold War. During both the Fed sat by—it was then still focused on keeping the prices of Treasury bonds high. The inflations soon passed away.

Before those came the World War I episode. That episode of inflation was cut off by an increase in the discount rate from 3.75%/year to 7%/year, which not only ended the inflation but enforced deflation: a 20% decline in the price level from its peak. (This decline, I should ask, made the task of restoring the gold standard at anything like pre-World War I nominal parities much more difficult, hence much more pointless.) Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz judged that the rise was “not only too late but also too much” <https://archive.org/details/monetaryhistoryo0000frie/page/230/>: the Fed should have moved earlier to prevent excessive bank discounts from inappropriately boosting high-powered money, and at the moment the Fed did move the structure of credit was sufficiently based on a continuation of Fed policy that the Fed’s move generated “one of the most rapid declines [in economic activity] on record”.

If the Federal Reserve had not moved to raise discount rates after World War I, what would have happened? Friedman and Schwartz’s judgment is that an earlier increase of, say, 125 basis points to remove the incentive for banks to engage in excessive discounts would have brought the excessive growth of the high-powered money stock to an end, and stopped the inflation.

Then came the 1970s: The Fed raised interest rates after the Yom Kippur War oil shock to control inflation; then, after inflation peaked, it lowered them to try to restore full employment; then came the year when, as the late Charlie Schultze said, “our forecasts of nominal income growth were dead on, but inflation came in 2%-points high and real growth 2%-points low”; and then came the Volcker disinflation, reversed in September 1982 when they realized that they had bankrupted Mexico, and not resumed as the Fed decided to declare a fall in inflation to the 4-5%/year range as complete victory. That 4-5% target lasted for a decade, followed by the opportunistic disinflation down to and Alan Greenspan’s declaration of the 2%/year inflation target—a declaration that it is very hard today to argue was appropriate, given the extraordinary amount of time global north economies have spent with interest rates at their zero lower bound since.

What does macroeconomic theory tell us that the Federal Reserve should do now, in the spring of 2022?

Olivier Blanchard writes:

In early 1975, core inflation was running at 12 percent and the real policy rate was equal to about −6 percent, a gap of about 17 percent. Today, core inflation is running at 6 percent and the real policy rate is equal to −6 percent, a gap of 12 percent—smaller than in 1975, but still strikingly large…. It then took 8 years, from 1975 to 1983, to reduce inflation to 4 percent, with an increase in the real rate from bottom to peak of close to 1,300 basis points, and a peak increase in the unemployment rate of 600 basis points from the early 1970s. Today is obviously different in many ways…. [But even so,] it reasonable to think that a 200-basis-point increase in the policy rate, so only 1/6 of the rate increase from 1975 to 1981, will do the job this time when the gap between core inflation and the policy rate is 2/3 of what it was in 1975? And that unemployment will barely budge? I wish I could believe it… <https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/why-i-worry-about-inflation-interest-rates-and-unemployment>

The suggestion seems to be that we have today 2/3 of the problem we had in 1975, and so the solution would be to do 2/3 as much—to raise interest rates by 800 basis points, 8% points—but then to apply some haircut to that 800 basis-point interest-rate rise because “today is obviously different in many ways”.

But why does he pick 1975-1983, rather than 1951 or 1948 or 1920? Does economic theory tell him to do so?

Truth be told, there is no economic theory. There is only history, and its events, and analogies we make based on judgments concerning complicated emergent processes we do not understand very well that come out of the millions of interactions that are the economy. Sometimes, it is true, we distill and crystallize the history into something we call theory where little squiggles that look like ɣ, δ, β, σ, and so on; we then mainline the crystallized product. After mainlining it we can think we know something. But after mainlining crystal meth we experience increased energy, elevated mood, extraordinary confidence, racing thoughts, muscle twitches, and rapid breathing, among other things.

Move cautiously. Be data-dependent. Wait for it to become clearer which, if any, historical analogies are relevant to our situation. And always, always, always remember that in an economy that is near and that we have a good reason to fear will long remain in danger of hitting the zero lower bound on nominal interest rates, premature and excessively aggressive moves that raise interest rates cannot easily be corrected.

One Video:

Paul Krugman: The Economics of Russia’s Ukraine Invasion <https://www.krugmantoday.com/today>

One Picture:

Very Briefly Noted:

Sarah Toy: Ivermectin Didn’t Reduce Covid–19 Hospitalizations in Largest Trial to Date: ‘Patients who got the antiparasitic drug didn’t fare better than those who received a placebo… <https://www.wsj.com/articles/ivermectin-didnt-reduce-covid-19-hospitalizations-in-largest-trial-to-date-11647601200>

Ben Steverman: Baby Bonds Eyed as Way to Close U.S. Racial Wealth Gap: ‘Pundits and politicians frequently talked of a “culture of poverty” or a “pathology” in Black “ghettos.” That didn’t compute for [Darrick] Hamilton… <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2022-03-17/baby-bonds-eyed-as-way-to-close-u-s-racial-wealth-gap?cmpid%3D=socialflow-twitter-economics>

Stephen Broadberry & Mark Harrison,: The Economics of the Second World War: Seventy-Five Years on<https://voxeu.org/content/new-ebook-economics-second-world-war-seventy-five-years>

Josh Rovner: Ukraine’s Lessons for Taiwan: ‘Taiwan could best prepare… by ensuring the right kind of defense strategy and capabilities… “systems that are short-range and defensive, able to survive an initial bombardment from a larger adversary, and suitable for deployment close to home in defense of the island… <https://warontherocks.com/2022/03/ukraines-lessons-for-taiwan/>

Fritz Fischer: Germany’s Aims in the First World War <https://archive.org/details/germanysaimsinfi0000fisc/page/482/mode/2up?view=theater>

Daniel Waldenström: Wealth & History: A Reappraisal: ‘Wealth… once held by the elite, it is now widely held in the form of housing and pension[s]… account[ing] for the redistribution of wealth over the last century and the fact that its concentration has remained relatively low… <https://voxeu.org/article/wealth-and-history-reappraisal>

Wojciech Kopczyk & /Eric Zwick: Business Incomes at the Top <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.34.4.27>

Heidi Blake: From Russia With Blood: 14 Suspected Hits On British Soil That The Government Ignored: ‘British fixer Scot Young[’s]… gruesome death is one of 14 that US spy agencies have linked to Russia–but the UK police shut down every last case… <https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/heidiblake/from-russia-with-blood-14-suspected-hits-on-british-soil>

Twitter & ‘Stack:

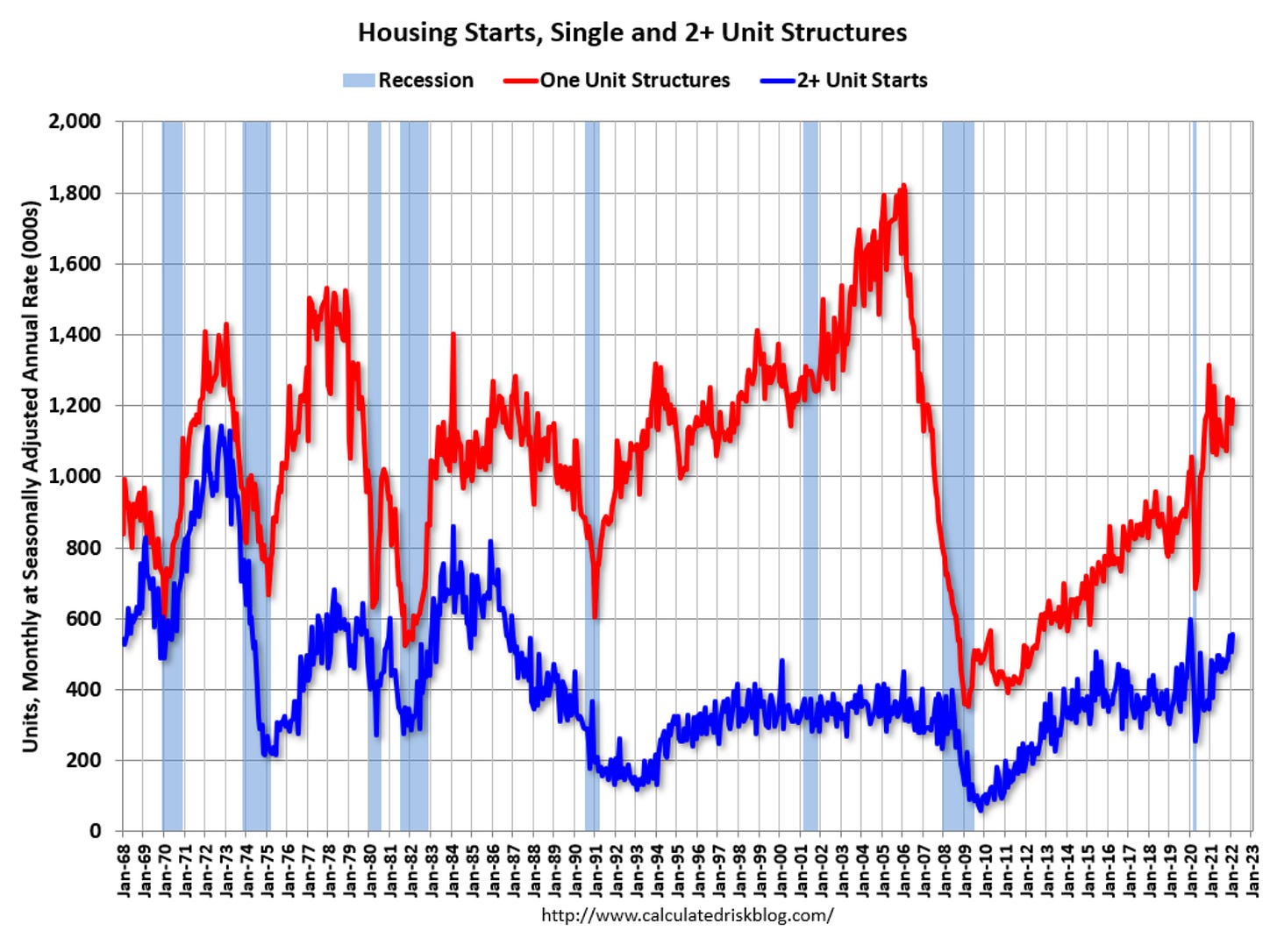

Bill McBride: February Housing Starts: Most Housing Units Under Construction Since 1973: ‘Housing Starts Increased to 1.769 million Annual Rate in February… <

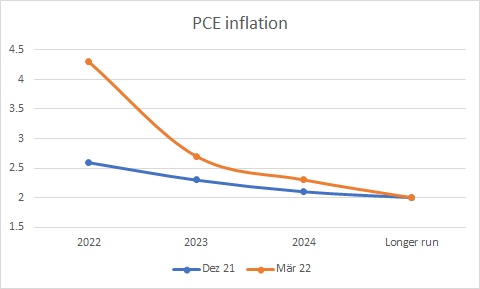

Stefan Gerlach: ’The FOMC’s projections… while the Fed no longer refers to “transitory inflation,” FOMC members think it will be back close 2% already next year…

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez: ’Imagine living in the US today, where the #1 source of domestic terrorism is far-right groups(per FBI!), books about slavery are getting banned, parents are criminalized for trans kids, yet asserting the 1st amendment is about protecting bigots from feeling embarrassed in public. I’m on team “embarrassing racists is our first amendment right, not their first amendment violation” thanks…

Adam Tooze: China Under Pressure: ‘A changing of the guard…. Li Keqiang is retiring…. Liu He cannot be far behind…. [China’s] future depends on facing domestic challenges both in the medium and the short-term. If Beijing suffers a devastating Omicron outbreak in the next few months the entire narrative of the period since 2020 will have to be rewritten…

Matthew Yglesias: Taking Putin’s Ideas Seriously (& I Guess Literally, too): ‘Lenin… worldwide… revolution… Russian Soviet Federal Republic and Ukrainian Soviet Federal Republic… soon be joined by Hungarian and Polish and German and French SFRs…. So rather than… Russification… Lenin instituted… Korenizatsiya (nativization)…. All.. analyses… can’t argue people out of the[ir]… distinct national and ethnic identity. None of these things are “real” anyway…

PAID SUBSCRIBER ONLY Content Below: Paragraphs &

Paragraphs:

Darrick Hamilton is finally getting some of the public-sphere mindshare he deserves! It is very nice to see:

Ben Steverman: Baby Bonds Eyed as Way to Close U.S. Racial Wealth Gap: ‘Pundits and politicians frequently talked of a “culture of poverty” or a “pathology” in Black “ghettos.” That didn’t compute for [Darrick] Hamilton. “I could see the vivid inequality,” he says, but “I could see fundamentally people were not different.” The neighbor he played football with who was later incarcerated for robbing an armored car didn’t seem essentially different from the classmate who might be an investment banker today…. One of his cornerstone ideas, to give “baby bonds” to each child, is being embraced and implemented by governments across the U.S. He insists, though, that this success shouldn’t be celebrated as a triumph over adversity. He despises the way classic rags-to-riches stories can be used to cast blame on those who can’t climb out of poverty. Such narratives ignore the economic stratification that can make success possible only with extraordinary luck or inhuman levels of personal sacrifice…

It has been hard to understand the attitude of many Republicans towards Donald Trump and company without the idea that, at some level, they are for some reason personally frightened. It has, I think, been a major failure of the British government that it has allowed Putin’s FSB to extend its tentacles the way it looks as though it has:

Heidi Blake: From Russia With Blood: 14 Suspected Hits On British Soil That The Government Ignored: ‘Lavish London mansions. A hand-painted Rolls-Royce. And eight dead friends. For the British fixer Scot Young, working for Vladimir Putin’s most vocal critic meant a life of incredible luxury–but also constant danger. His gruesome death is one of 14 that US spy agencies have linked to Russia–but the UK police shut down every last case. A bombshell cache of documents today reveals the full story of a ring of death on British soil that the government has ignored…

This raises the huge question that I wish not this book but another book would deal with: what will the social practice of war look like in the 21st century? It is all about getting the local police officer on the ground to follow your and not somebody else’s instructions. How will that be accomplished?:

Stephen Broadberry & Mark Harrison: The Economics of the Second World War: Seventy-Five Years on: ‘Inaugurated by a transport innovation… railways to concentrate and deploy a mass army of a hundred thousand men in… 1859…. Thereafter, railways dominated the logistics of the great land offensives of the two World Wars. The era ended in the 1970s, Onorato et al. maintain… [as] innovation… took away the point of mass armies by converting them from instruments to sitting targets…

LINK: <https://voxeu.org/content/new-ebook-economics-second-world-war-seventy-five-years>

Would you rather have America’s or China’s hand to play over the next fifty years? Or, rather, who would you have to be to rather have America’s hand? And who would you have to be to rather have China’s hand?

Adam Tooze: China Under Pressure: ‘A changing of the guard…. Premier Li Keqiang is retiring and Vice Premier Liu He cannot be far behind. Once they were Xi’s point men on the economy. They leave the main stage amongst considerable turmoil. Ukraine has thrown Xi’s geopolitics off balance and rallied the United States and its allies. The dramatic transition in China’s domestic economic policy is continuing to cause a major shakeout. Last year China was dealing with an energy crunch. Now growth has slumped in Q4 2021 to 4 percent…. Ultimately, what matters most is that China sustain its position as the leading driver of global economic growth…. How far “common prosperity” is really a comprehensive new formula and new vision of growth remains to be seen…. If Beijing suffers a devastating Omicron outbreak in the next few months the entire narrative of the period since 2020 will have to be rewritten…

LINK:

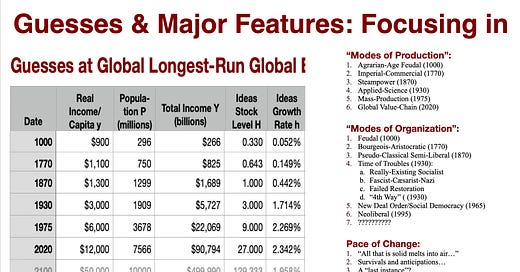

Subject: My “Behind the Iron Curtain” Lecture for “History of Economic Growth”

It now looks as though, given all the slides I have and everything I have written down in the lecture notes, it would be six hours long. It can only be 1 1/2—I have too many other things I need to cover.

Here is a chunk from it:

6.1.3. The Marxist Faith

6.1.3.1. Lenin’s Faith: The relatively small group of socialist agitators that had gathered under Lenin’s banner before the revolution and cut their teeth during the years of civil war began their task with a faith-based expectation of help. Because the Marxist-Engelsian sciences of dialectical and historical materialism had told them so, Lenin and his comrades confidently expected their revolution in Russia to be followed by other, similar communist revolutions in the more advanced, industrial countries of Western Europe. Once they were communist, they believed, these countries would provide aid to poor, agrarian Russia, and so make it possible for Lenin to stay in power as he guided his country to a stage of industrial development where socialism might function the way Marx had promised it would. Lenin pinned his hopes on the most industrialized country in Europe, with the largest and most active socialist political party: Germany. A communist republic briefly held power in Hungary. Another one briefly held power in Bavaria, in southern Germany. But, in the end, the Russian Revolution was the only one that stuck.

Thus the story of building an alternative to market-capitalist society—building really-existing socialism—in one and only one very poor and non-industrialized country began.

6.1.3.2. The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”: Really-existing socialism—distantly descended from the idea of Marx, Engels, and company—was the interpretation of a dream, implemented via something called the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” That first word, “dictatorship,” meant, for the phrase’s coiner, Joseph Wedemeyer—as it meant for Marx and Engels—the temporary suspension of checks and balances, procedural impediments, and established powers, so the government could make the needed changes and actually govern—violently, when necessary, to overcome reactionary opposition. Originally it meant the same non-permanent thing for Lenin.

But in whose interest would it govern?

In Lenin’s mind, that concentrated power would be administered for the proletariat. Why not just have a dictatorship of the people—a democracy? Because, Lenin believed, all society’s non-proletariat classes had selfish interests. To allow them any political power during the initial post-revolutionary dictatorship would only retard the inevitable progress of history. Which was toward utopia. Which was true socialism.

6.1.3.3. Fixing the 20th Century Meaning of “Socialism”: I trust I give little away when I tell you, really-existing socialism was, in the hands of its disciples, to become the most murderous of the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century. Admitting this now can, and should, help focus our attention.

Until it really existed, “socialism” could mean many things—things other than the system Lenin created and Stalin solidified. In Western Europe and North America during the World War I era, most who called themselves any flavor of “socialist” held that in a good society there ought to be enormous scope for individual initiative, for diversity, for the decentralization of decision-making, for liberal values, and even for non-commanding-heights private property. True freedom was, after all, the point. Eliminating the unequal distribution of income under capitalism that kept the bulk of the formerly free imprisoned in the same life of drudgery and imprisonment was the goal.

In price regulation and in public ownership, the question was an empirical one: private where private belongs, public where it was needed. And most people trusted representative democracy and rational argument to settle things case by case. But others took a more radical view, pushing for something beyond even a reformed, well-managed, and gentler market economy. It wasn’t until Lenin began to exercise power that people began to discover the tradeoffs that would be involved in a really-existing socialism focused on destroying the power of the market.

6.1.3.3. Marx’s Optimism About History: Lenin, his followers, and his successors began with a general article of faith: Karl Marx was right. In everything. If properly interpreted.

Marx had mocked the sober businessmen of his time. They claimed to view revolution with horror. Yet, Marx asserted, they were themselves, in a sense, the most ruthless revolutionaries the world had ever seen. The business class—what Marx called the bourgeoisie—was responsible for the (up to then) greatest of all revolutions, and that revolution had changed the human condition. For the better. After all, it was the business class of entrepreneurs and investors, together with the market economy that pitted them against one another, that was responsible for bringing an end to the scarcity, want, and oppression that had been human destiny heretofore.

6.1.3.4. Marx’s Pessimism About Capitalism: But Marx also saw an inescapable danger: the economic system that the bourgeoisie had created would inevitably become the main obstacle to human happiness. It could, Marx thought, create wealth, but it could not distribute wealth evenly. Alongside prosperity would inevitably come increasing disparities of wealth. The rich would become richer. The poor would become poorer, and they would be kept in a poverty made all the more unbearable for being needless. The only solution was to utterly destroy the power of the market system to boss people around.

My use of “inescapable” and “inevitable” is not for dramatic effect. Inevitability was for Marx and the inheritors of his ideas the fix to a fatal flaw. Marx spent his entire life trying to make his argument simple, comprehensible, and watertight. He failed. He failed because he was wrong. It is simply not the case that market economies necessarily produce ever-rising inequality and ever-increasing immiseration in the company of ever-increasing wealth. Sometimes they do. Sometimes they do not. And whether they do or do not is within the control of the government, which has sufficiently powerful tools to narrow and widen the income and wealth distribution to fit its purposes.

Marx, however, decided to prove that the existing system guaranteed dystopia:

The more productive capital grows, the more the division of labor and the application of machinery expands. The more the division of labor and the application of machinery expands, the more competition among the workers expands and the more their wages contract. The forest of uplifted arms demanding work becomes thicker and thicker, while the arms themselves become thinner and thinner…

Marx was also certain that his dystopian vision of late capitalism would not be the end state of human history. For this bleak capitalist system was to be overthrown by one that nationalized and socialized the means of production. The rule of the business class, after creating a truly prosperous society, would “produce . . . above all . . . its own gravediggers.”

6.1.3.5. Marx’s Vagueness About Utopia: What would society be like after the revolution? Instead of private property, there would be “individual property based on . . . cooperation and the possession in common of the land and of the means of production.” And this would happen easily, for socialist revolution would simply require “the expropriation of a few usurpers by the mass of the people,” who would then democratically decide upon a common plan for “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally.” Voilà, utopia.

6.1.4. Building Really-Existing Socialism in One Country

6.1.4.1. The Causal Thinness of the Bolshevik Revolution: Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Joseph Stalin, and a few others—rounding out the Soviet Union’s first Politburo were Lev Kamenev and Nikolai Krestinsky—were a small enough group that it is plausible to wonder what would have happened if different people with differing characters and different views had shaken out on top. They didn’t, and perhaps it was because these men were not just scholars and journalists, not just the inept and hopeful, but also sufficiently capable, timely, and ruthless.

6.1.4.2. What Lenin & Company Made: Lenin and his successors, all the way down to 1990, took the doctrines of Marx the prophet seriously. And they tried to make them real. But they were not gods. While they said, “Let there be true socialism,” what they made was, instead, really-existing socialism. It was socialism in that it claimed to have gotten as close to the hopes of Marx and other socialists as could be realized—but it was also enacted in reality, on the ground, in regimes that at their peak ruled perhaps one-third of the world’s population. It was not an intellectual utopian fantasy, but a necessary compromise with the messiness of this world. Really-existing socialism was, its propagandists and apparatchiks claimed, as close to utopia as it was possible to get.

6.1.4.3. Marx’s Probable Attitude to RES: Throughout most of really-existing socialism’s career, Marx would probably have regarded it with dismay and perhaps disdain—a frequent fate of prophets. To really exist, socialism had to depart in significant ways from the predictions (and the instructions) of the prophet. For, it turns out, not only do you have to break eggs to make an omelet, but the omelet you end up making—indeed, whether what you make can be called an omelet at all—depends a good bit on the eggs you have at hand. This matters, because Russia in the early twentieth century was not where any of the early theorists of what became really-existing socialism ever thought socialism would first really exist. And for good reason.

6.1.4.4. Régime Imperative: Survival: The first imperative Lenin’s regime faced was survival. But the first imperative the regime thought it faced was the elimination of capitalism by way of nationalizing private property and removing business owners from management. How, though, do you run industry and economic life in the absence of business owners—in the absence of people whose incomes and social standing depend directly on the prosperity of individual enterprises, and who have the incentives and the power to try to make and keep individual pieces of the economy productive and functioning? Lenin’s answer was that you organize the economy like an army: top down, planned, hierarchical, with under managers promoted, fired, or shot depending on how well they attained the missions that the high economic command assigned them.

6.1.4.5. The New Economic Policy of the 1920s: Initially, however, the building of really-existing socialism required stepping back from war communism and into the “New Economic Policy” of the 1920, which required letting prices rise and fall, letting people buy and sell and get richer, letting managers of government factories make profits (or be sacked), and letting a class of merchants and middlemen grow, as what Keynes called “tolerated outlaws.” It was an expediency. Capitalism, but subject to state control; socialized state enterprises, but run on a profit basis. And while the leash was rarely tugged, it remained.

6.1.5. Really-Existing Socialist Economies

6.1.5.1. How a “Command Economy” Has to Work: Part of the expedience was due to the fact that the centralized Soviet government had limited grasp. Even by the mid-1930s, the planners could only track material balances for about one hundred commodities. The movements of these were indeed centrally planned. Nationwide, producers of these commodities who did not fulfill their goals according to the plan were sanctioned. Otherwise, commodities were exchanged between businesses and shipped out to users either through standard market cash-on-the-barrelhead transactions or via blat: connections. Who you knew mattered.

When blat, market exchange, or central planning failed to obtain the raw materials an enterprise needed, there was another option: the tolkachi, or barter agents. Tolkachi would find out who had the goods you needed, what they were valued, and what goods you might be able to acquire given what you had to barter with.

6.1.5.2. Command vs. Market?: If this sounds degrees familiar, it should.

One hidden secret of capitalist business is that most companies’ internal organizations are a lot like the crude material balance calculations of the Soviet planners. Inside the firm, commodities and time are not allocated through any kind of market access process. Individuals want to accomplish the mission of the organization, please their bosses so they get promoted, or at least so they don’t get fired, and assist others. They swap favors, formally or informally. They note that particular goals and benchmarks are high priorities, and that the top bosses will be displeased if they are not accomplished. They use social engineering and arm-twisting skills. They ask for permission to outsource, or dig into their own pockets for incidentals. Market, barter, blat, and plan, this last understood as the organization’s primary purposes and people’s allegiance to it, always rule, albeit in different proportions.

The key difference, perhaps, is that a standard business firm is embedded in a much larger market economy, and so is always facing the make-or-buy decision: Can this resource be acquired most efficiently from elsewhere within the firm, via social engineering or arm-twisting or blat, or is it better to seek budgetary authority to purchase it from outside? That make-or-buy decision is a powerful factor keeping businesses in capitalist market economies on their toes, and more efficient. And in capitalist market economies, factory-owning firms are surrounded by clouds of middlemen. In the Soviet Union, the broad market interfaces of individual factories and the clouds of middlemen were absent. As a consequence, its economy was grossly wasteful.

Though wasteful, material balance control is an expedient that pretty much all societies adopt during wartime. Then hitting a small number of specific targets for production becomes thexf highest priority. In times of total mobilization, command-and-control seems the best we can do. But do we wish a society in which all times are times of total mobilization?

6.1.5.3. The State of the USSR in the Late 1920s: Let’s pause briefly to consider the state of the Soviet Union in the late 1920s. By 1927, the Soviet Union had recovered to where it had been in 1914—in terms of life expectancy, population, industrial production, and standards of living. The imperative of survival had been met. And there was no longer the deadweight of the czarist aristocracy consuming resources and thinking and behaving feudally. As long as Lenin’s successors could avoid destroying the country through their own mistakes, and as long as they could keep encouraging people to judge their management of things against a baseline of war and chaos, it would be hard for them to fall out of favor.

The recovered Soviet Union remained subject to existential threats, to be sure. Those in the upper echelons of Soviet government greatly feared that the capitalist powers of the industrial core would decide to overthrow their regime. Someday soon, their thinking went, the really-existing socialist regime might have to fight yet another war to survive. They remembered that they had already fought two: a civil war, in which Britain and Japan had at least thought about making a serious effort to support their enemies; and a war against Poland to the west. They were desperately aware of the Soviet Union’s economic and political weaknesses. To meet external threats, the Soviet leaders had ideology, a small cadre of ruthless adherents, and a bureaucracy that sort of ran an economy recovered to its 1914 level. What they didn’t have was time.

They were not wrong.

On June 22, 1941, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. Its aims were twofold: first, to exterminate Jewish Bolshevism as an idea, a political movement, and a regime; and second, to herd onto reservations, enslave, or exterminate the bulk of the inhabitants of the Soviet Union. The land they occupied was needed to provide larger farms for German farmers and more “living space”—Lebensraum—for the German nation.

6.1.5.4. “Primitive Accumulation” in the USSR: The Bolsheviks thought they were viewed by the non-socialist powers as an existential threat. And all the Bolsheviks agreed that to survive, Russia needed to industrialize rapidly. But how were they to persuade the peasants to boost agricultural production if they had no factory-made consumer goods to trade for their grain?

Marx had interpreted the economic history of Britain as one of “primitive accumulation.” Landlords had used the political system to steal land from the peasantry and squeeze their standard of living. This forced some of the peasantry to migrate to the cities, where they became a penniless urban working class. There, manufacturers and owners of means of production used the political system to force them to build and work in factories.

For Marx, this awful outcome was one of the things that made capitalism an obstacle to human development and flourishing. The Bolsheviks took Marx’s critique of British modernization and made it their business model. Not just Stalin, but Trotsky, Yevgeni Preobrazhensky, and others among the elite had concluded that rapid industrialization was possible only if the ruling communists first waged economic war against Russia’s peasants. They would squeeze their standard of living as much as possible in order to feed and populate the growing industrial cities. They would keep urban wages high enough to provide a steady stream of migrants to city jobs, but no higher.

6.1.5.5. The “Scissors Crisis”: This strategy was the first of what would ultimately become a series of Five-Year Plans.

The “goods famine” this policy generated shifted urban production from consumer goods to capital goods, and from light industry to heavy industry—ultimately bringing about a “grain famine.” The result was a “scissors crisis”: As the price of industrial goods manufactured in cities continued to rise to meet the government’s investment targets, the price of farm goods fell, and on the graph, the widening gap looked like a pair of scissors. Peasants unable to buy manufactures (and increasingly uninterested in doing so) were also unable to sell farm goods. The cities struggled to be fed, threatening the Five-Year Plan and Russia’s ability to industrialize, which Bolsheviks believed would determine its ability to survive.

It seems we are currently dealing with two misapplied analogies: in inflation fighting it is always 1975, and in international relations it is always Munich 1938.

Naively, it looks like inflation comes before a baby boom. The early 20th century rise seems to have been driven by immigrants who arrived in the late 19th century and started families around and after The Great War. The mid-20th century rise seems to have been driven by their children, including many World War II veterans, who started families in the late 1940s and into the 1960s. The late 20th century rise seems to have been driven by that group's children, mainly baby boomers, who started families in the late 1980s and into the 1990s.

Inflation rises when they are young adults looking for careers, buying homes, entertaining, attracting sexual partners and establishing themselves in the world. Then inflation abates as they get down to the business of raising children. In other words, naively, it looks like a demographically driven cycle, and that our current bout with inflation presages a rise in family formation and child raising starting in about five to ten years, let's say 2027-2032.

Was there a similar cycle in the 1870s, after the Civil War? I wouldn't be surprised, though the I'd expect the economic indicators to look a bit different as so much has changed in the economy since then. (There was generational nostalgia for the Gay 90s which fits the pattern for people of that generation idealizing their salad days.)

Again, I'm being deliberately naive here.