The real thing will live at: <http://delongtoday.com>…

Today is an anti-economic history briefing.

Back 90 years ago, in another depressing time—one of depression, if not of depression and plague—John Maynard Keynes tried to cheer people up by talking about the bright “economic possibilities for our grandchildren”. And we are they. Or, rather, we are their great-grandchildren and great^2-grandchildren.

So let me attempt a similar exercise.

How should we understand, from the most Olympian perspective, from a super-Olympian perspective, not the past but the future of the process of economic growth that the human race has undergone over the past half-millennium?

So let us look at our great- and great^2-grandchildren and what are their economic possibilities in 2100, then our great^5-grandchildren in 2200, and then all the way out to the year 2525: our great^15-grandchildren.

That is not that far out. Yesterday Amazon drop-shipped me a book about one of my ancestors back in the 1500s: Thomas Wyatt the Younger, executed on Tower Hill on orders of Bloody Mary for being an unwise catspaw for nobles who wondered if they could persuade Parliament to take control over the Queen’s marriage, to prevent the accession of a Spanish King who would bring the Inquisition to England. The answer was no: they could not persuade Parliament to mobilize the military force to threaten convincingly. We are connected to him, and there are those in 2525 who stand in a similar connection to us…

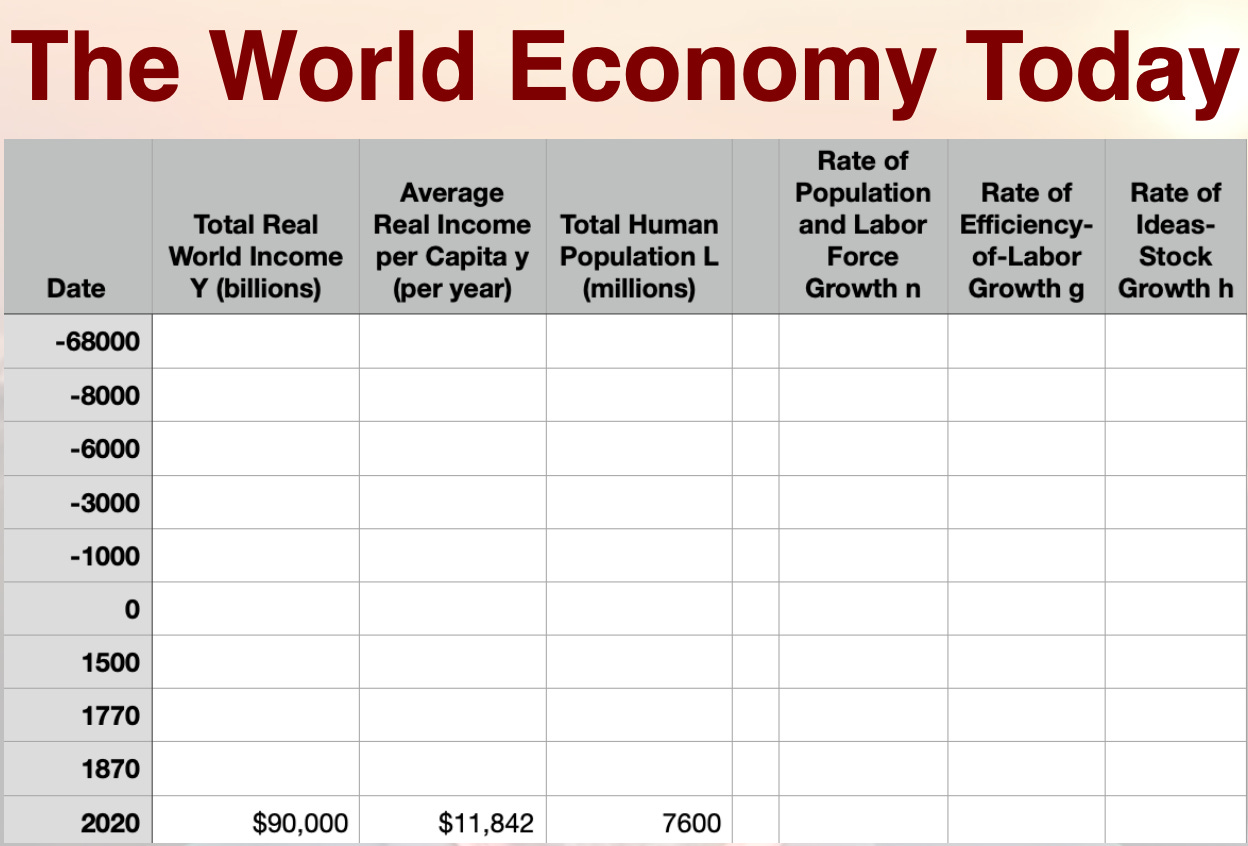

Let us start with the world economy today. 7.6 billion people. Average annual income per capita a hair under 12,000 international dollars a year. A $90 trillion a year world economy.

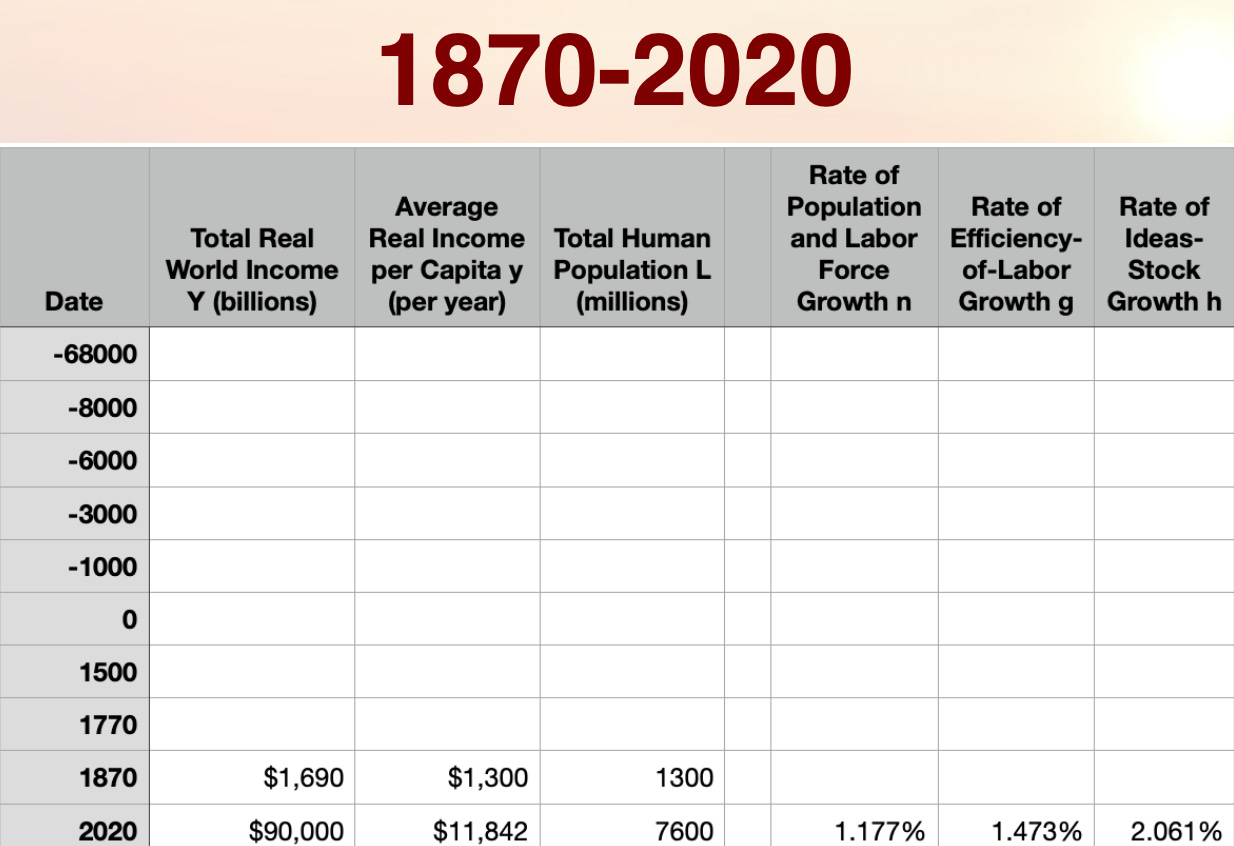

We have consensus estimates for how the world economy has evolved over the past 150 years. They tell us that 150 years ago, back in 1870, the world had a total global income of $1.7 trillion dollars, with 1/9 of our average income per capita: $1300 rather than a hair beneath $12000. Thus since 1870 human numbers have grown at 1.2%/year and human real incomes at 1.5%/year. Our higher population means that we have fewer resources available per worker as the world’s endowment has to be split more ways. This has put an approximately 0.6%/year drag on our rate of income growth. That means that the underlying driver of humanity’s economic growth—the discovery, development, and deployment of ideas about how to manipulate nature and organize humans—the value of the stock of humanity’s economically useful ideas has grown at 2.1%/year over the past century and a half.

Now there are deep conceptual problems with this statement. Economists call them “the index number problem”, but that implies that they are (a) boring and technical, and (b) solvable, at least for practical purposes. They are not. Let me try to make them real. Consider Nathan Mayer Rothschild, who died in 1836.

He was, then, the richest man in the world.

He died in his 50s, younger than I am now.

He died of an infected abscess in his butt. How much of his wealth would he have paid for the single dose of amoxicillin, with which our nurses’ aides would cure an infected abscess in each of our butts had we occasion? At his death Nathan Meyer Rothschild was worth $600 million 2020-dollars. (The richest man in the world and only $600 million, you say? Yes, the world of the past was much poorer than the world of the present. Nsthan Mayer Rothschild would have been willing to pay $600 million. There is a profound sense in which each and every one of us, by virtue of public health alone, is vastly richer than Nathan Meyer Rothschild was. On the Nathan Mayer Rothschild’s preferences scale, we are all centimillionaires, by virtue of our state of public health alone.

That is just one dimension. Let us consider another. If it happened to be 1610, and if you wanted to see a gory horror video entertainment about witches in your home, you had better be named James Stuart, you had better be King of England and Scotland, and your acting company—the King’s Men, led by William Shakespeare—had better have Macbeth currently in repertory.

Figure, with acting time, rehearsals and scenery construction, et cetera, that it would have required 400 person-hours of work to put on the play. I—and at least half the population of the United States—can do that and much, much more for $0.60 cents’ worth of broadband connectivity, plus perhaps another $0.90 of computer and TV amortization. Charging that cost at today’s typical $50/hour labor rate, we see that the real labor-time cost is not 400 hours but 1 minute: 24000 times cheaper. And I don’t have to watch MacBeth. I can watch something else—any of thousands of other things. And I can watch dozens of different performances of MacBeth, depending on my fancy of the moment.

No: to say that average income per capita was $900/year in 1600, $1300/year in 1870, and almost $12000/year today does not capture it, for we produce and use not just more of what they produced and used, but things close to the edge of if not beyond their imagination, powers and capabilities and experiences that they saw as reserved to godlike beings.

But let us run with the consensus estimates we have: the world in 1870 had a total global income of $1.7 trillion dollars, and 1/9 of our average income per capita. Since 1870 human numbers have grown at 1.2%/year and human real incomes at 1.5%/year, for a rate of ideas growth of 2.1%/year. That has brought us to our current world of 7.6 billion people and $90 trillion of world annual income, for an income per capita average level a hair under $12,000/year.

So what will the world be like in 2100?

The first thing to note is that humanity appears to be headed for zero population growth. The population explosion—from 1.3 to 7.6 billion people over the past 150 years—has been driven by inherited patterns of thought from the more distant past. Before the Industrial Revolution and Modern Economic Growth, you see, human populations grew glacially on average. Between the year 1 and 1500 the average population growth rate was 0.073%/year—2% per generation. Thus the average couple had 2.04 descendents who survive to themselves reproduce. The Poisson distribution then tells us that the typical reproducing couple had a 13% chance of themselves having no descendants who reproduce. And that is an important number. For to be in that 13% was, potentially, disastrous.

Have no surviving descendants in the pre-Social Security age, you see, means that you have no social power when—if—you reach old age. Yes, you have property, but you cannot work it, and who will care enough to protest if somebody takes it away from you? Thus people back in the old days sought to have enough children that they could be confident that at least one would survive to provide them with at least some social power, should they be lucky enough to have a long old age. And 13% of couples failed.

Thus when humanity became richer and public health improved, it took several generations for human habits to catch up, and for people to realize that they were not under strong pressure from necessity to try to have large families. And it seems that, in a world of low infant mortality and Social Security, the typical couple worldwide really does not wish to have more than two children. Therefore figure that the world population will stabilize around 9 billion sometime over the next century. It certainly will not grow from 7.6 to 30 billion, which it would if we were to continue the past 150 years’ trend. It may shrink.

Up until 2100, continued growth of the value of the deployed stock of useful economic ideas at the 2.1%/year of the past 150 years is highly likely. Indeed, it is all but baked into the cake. The overwhelming bulk will simply be from the spread to the global south of productive ideas already deployed and in use in the global north.

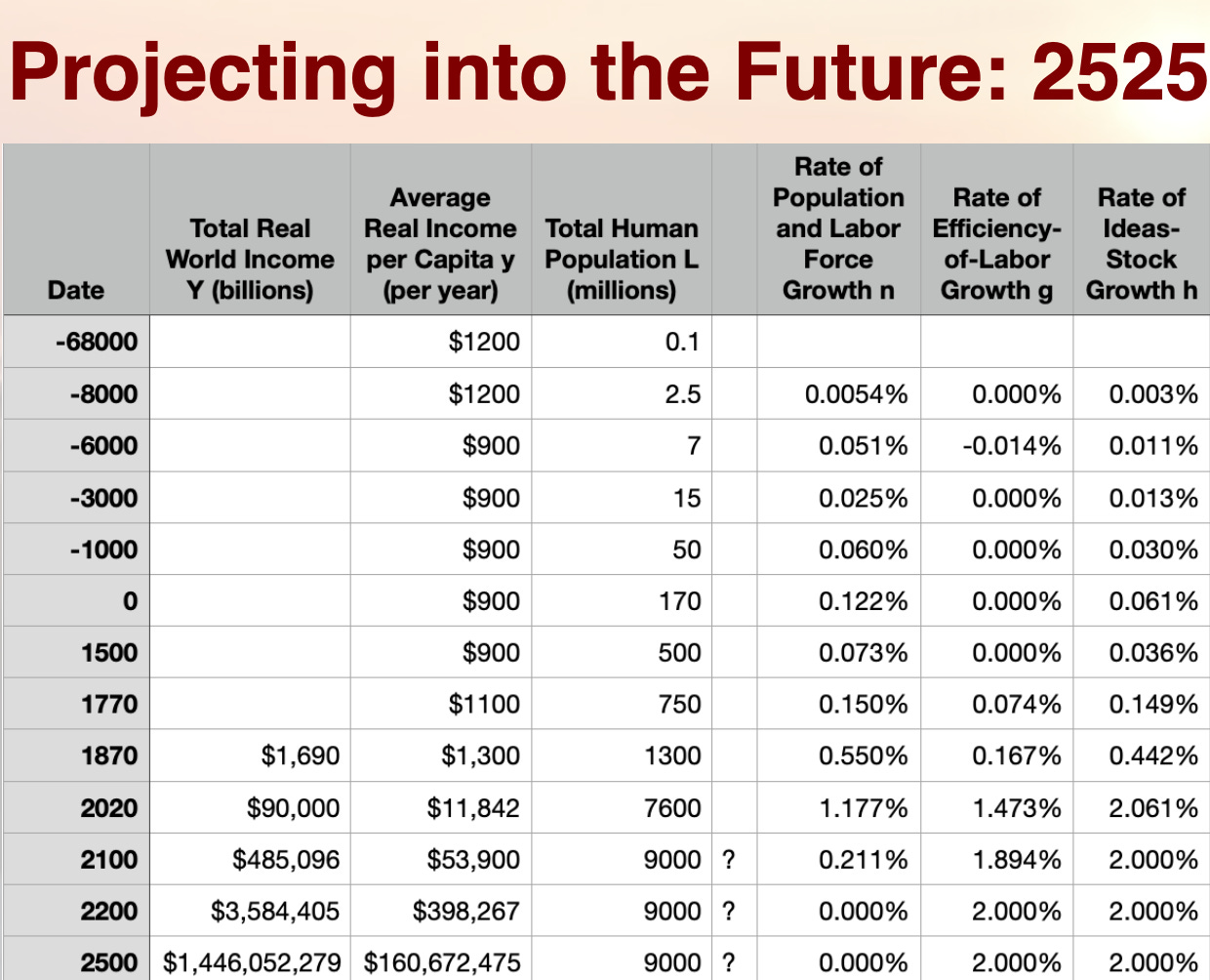

With a population of 9 billion, and a deployed-ideas stock in 2100 that is, a 2.1%/year growth rate tells us, 5 times its current worldwide value, we can thus look forward to a world in 2100 where 9 billion people have a typical income of $55,000/year for a global world income level in 2100 of $500 trillion. The human then with an income that is the world average will live like an inhabitant of the global north with an income that is the global north average lives today. That would be, from our perspective, not yet a truly human world—but one in which such a truly human world might be within sight, if not yet at hand.

And suppose we manage to maintain the 2.1%/year rate of ideas growth that modern science, modern engineering, and the capitalist market world economy has delivered for us since 1870 for a further century, to 2200? What might the world be like then?

Well, assume continued population stability, and confront the terrifying power of compound interest: a quantity growing at 2.1%/year multiplies itself eightfold over a century. Eight times the ideas stock in 2200 than 2100 would give us a world with global annual income of $3600 trillion, with the average share then being $400,000/year. The person with an average share would then live as well—but in different ways, to be sure, that we cannot well imagine—as one of America’s top 1% lives today.

The story of modern human economic society, of economic growth and the escape from Malthusian stagnation and its poverty, want, and famine, really starts in 1500, 500 years ago, with the Commercial-Imperial Revolution. If we invoke the principle of mediocrity—that we are not special, being neither at the beginning nor at the end—we then find it appropriate to suppose that we are only halfway through this process of modern economic growth.

If it continues at its 2.1%/year rate to a point 500 years from now, we then imagine a world in 2525—if man is still alive, if woman can survive, we may find…

What we then find is a world in which global annual income is $1,446,052,279,000,000,000—that is, $1.5 sextillion. The person receiving the average share of that income in 2500 would then have $160 million to spend. We are now talking large jetliners and private islands as the personal possessions of a typical human, come 2500, if the principal of mediocrity applies, if we are only halfway through the process, if modern economic growth continues to that day.

And if we are only a third of the way through the process? Something that multiplies eightfold in a century multiplies 30,000 fold in a half-millennium. That would give the typical human in 3000 $5 trillion—5% of this year’s total world income—to spend on his or her personal projects each and every year.

The world of 2100 with a $50,000/year average income is easy to imagine. That future for the world is, largely, here today in the global north. It is a future built by large-scale deployment elsewhere of technologies already tested and in use, with further developments, plus advances many of which we can see: clean technologies, mRNA and other biotechnologies, further advances in semiconductor hardware production and in algorithms to deploy computer power, perhaps quantum computing, perhaps room-temperature semiconductors. The world of 2200 is much harder to imagine, but it can be done: it merely needs robots and other new technologies to take a further 7/8 of the work we now do off of our and into their hands, so that we spend one hour directing and then they accomplish what would today take a typical worker in the global north an entire day.

But the world of 2500? We today have, by our consensus estimates, 15 times the income of 1500. The global north has 60 times the income of 1500. The top 1% in the U.S. has 120 times the average income of 1500. But the simple-extrapolation world of 2500 has an average income level 400 times that of the U.S. top 1% today. The technologies that would provide that level of power over nature for everyone really are beyond our imagining. They require that nature have deep secrets, either at the fundamental or at the matter-organization level, of which we are now completely ignorant.

You might reply: People back in 1500 were equally ignorant of the deep secrets of nature that we have uncovered and that drive our technologies. And that is true. Moving outward from my eyes we have (a) air heated by a natural gas furnace (instead of a wood fireplace with a chimney), a cotton shirt spun and woven by machine, the arm of a wooden couch varnished with sophisticated petrochemical products, (d) a machine-made ceramic mug with a “Batman” logo, (e) tea rewarmed by a microwave oven, (f) a ceramic coaster, (g) a printed book, (h) a leather couch cushion stuffed with machine-made petrochemical-derived artificial fibers (not wool), (i) an Apple watch, (j) a gold wedding ring, (k) an Apple MacBookPro, (l) an LED ring light. We see technologies people in 1500 knew—or at least had heard of—plus textile and ceramics machinery, carbon energy, organic petrochemistry, plus making electrons get up and dance as a power source—for lighting and heating—plus making electrons in semiconductors get up and dance in patterns for information and communications technology. But the alchemists of 1500 knew that they did not understand chemistry at all, and had no idea of electrons—and nobody had any idea they could be induced to dance at all until Jean-Antoine Nollet in 1740.

But the difficulty today is that we do not see any empty, unknown spaces on our maps of science out of which new technologies useful at human scale might emerge. Some things unknown appear to happen at too high energies at too small length scales. Other things unknown appear to happen at cosmic distances ever eons. Both seem forever remote from human experience.

No. I have to conclude that the odds are overwhelming that the 2.1%/year ideas growth rate of modern economic growth will come to an end, and well before 2500. I have to conclude that we are not in the middle but, rather, closer to the end of the adventure that began in 1500. Exponential growth is rarely the rule, after all. Exponential growth in early stages followed by some sort of near-exponential convergence to a steady-state of some sort seems much more the rule.

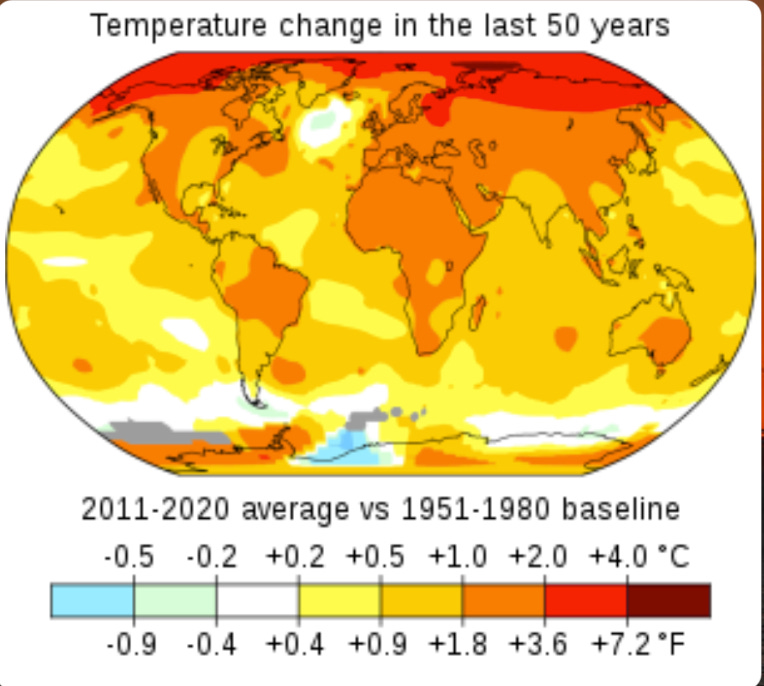

Is this all not grossly overoptimistic? Won’t global warming come to kill us all?

I now think the answer to that is: no. Our clean-energy technologies are improving at a mighty pace. Yes, we should have provided mighty incentives to develop clean energy, to deploy clean energy, and to penalize carbon pollution at least 30 years ago. Yes, scorn and shame and—I think—prison time would be a just reward to all those who have worked so hard to block the world’s proper response. Yes, global warming is going to be catastrophic and deadly for tens of millions and millions. Yes, we will wind up with a very different world 5F or—though I really hope not—10F warmer. But I expect carbon-powered power-plant construction to stop now, carbon-powered vehicle production to stop in 10 years, and for the retirement of carbon-emitting capacity to take place over no more than one more generation. And I expect this to happen, overwhelmingly, for technological and cost reasons rather than for regulatory and penalty ones—although a powerful driver of the technological shift is that governments will allow people to profit from inventing green energy and conservation technologies, but not to profit from inventing carbon-emitting ones.

There are, however, two big reasons to be relatively pessimistic about the future of human civilization—to not see the human future as one in which our descendants several centuries hence are comprised of a stable world population of 9 billion, each with the standard of living of the U.S. 1%-ers today.

The first is that, while we are more peaceful than most of our close relatives, we are not that peaceful.

Males, especially, are irrational creatures who fall into fits of emotional rage and do not properly calculate the costs of blowback from choosing violence. And technology has given us weapons which may someday kill us all. We could even destroy our civilization without using nuclear weapons: drones are cheap and hard to spot, and are getting cheaper and harder to spot. And nitrogen bonds have enough energy in them to do all the blowing-up and killing anyone could ever wish, and more.

The second is Enrico Fermi’s question: Where are all the aliens?

If we were outside the solar system, looking in, by now we would see a strange bump in the solar system’s electromagnetic signature in the radio frequencies. If aliens outside looked closer, they could see us. But when we look out at the universe, we do not see them. Where are the aliens? As best as we can tellm the number N, the number of visible civilizations made up of intelligent, communicating beings in our galaxy is equal to one: us.

Now the number of civilizations we should see…. Each year roughly one star is formed in our galaxy. We now know that pretty much every star has planets, and that pretty much every star with planets has a planet where water is liquid and so our kind of organic chemistry works. Suppose that every such potentially-habitable planet developed life, and every biosphere developed one species of intelligent life, and every form of intelligent life developed a civilization visible across intersteller distances, and every intelligent species’s civilization lasted for 10 million years—only an eyeblink in the life of a planet. Then we should look out at the stars of our galaxy, and we should see the 10 million civilizations of all of our cousins in the sky.

The argument generalizes: if f(l), the fraction of potentially-habitable planets that develop life, f(i), the fraction that then develop intelligence, and f(c), the fraction that then develop a civilization visible across interstellar distances are all roughly one, then in order for us to see only one civilization the typical civilization has to be visible for only one year before it bombs or plagues or biosphere-upsets itself back to the stone age. If f(i) = 1% and f(c) = 1%—if intelligent life and industrial civilization are both longshots—then the galaxy should see a new visible civilization emerge every 10000 years, and that we see zero besides ourselves tells us that they do not last long in terms of planetary or even species lifetimes. Unless we have already passed through a “Great Filter”—unless the chances are astronomically against life developing or structures like our brains, mouths, and ears developing or industrial civilization developing—the odds are then that our civilization does not have long before a fatal accident befalls, at least if “long” is taken in the perspective of a time scale like that of the time since our divergence from the chimpanzees.

Now it might be a good thing that we do not see other civilizations: if we did, we might have seen them in the form of the Borg or of the Fascist Aprahant Butterfly Terror come to assimilate us. But that we did not see them should give us pause, should spur us to thought about what we can and should do to guard against civilization-scale threats.

This is the DeLongTODAY Bradcast Briefing. I’m Brad DeLong. Thank you very much for watching.

3471 words

I'm not naturally optimistic, but I think you are too pessimistic on the technology front. We have just entered the golden age of materials science and just getting glimpses of what is possible with nano-structures, bio-mimetics, non-traditional metallurgy, meta-materials and in a host of other areas. We can actually do more with a lot less. For example, spin, as opposed to charge, based electronics is much faster and uses much less power. New classes of reflective and transmissive materials could change the way we heat and cool spaces.

One thing to consider is how much of that 2.1% technological growth has changed the commons. Rothschild couldn't have bought a modern antibiotic, and neither can you. You can only "buy" amoxicillin because we have a medical-pharmacological-health insurance-research complex. Even today, in many countries, individuals do not buy things like amoxicillin. Civilizations do. Rothschild couldn't have bought a highway to Berlin, let alone a high speed train system or whatever may come next. Those require an advanced commons. If you look to the future, it pays to think about what the commons can deliver, rather than individual components of it.

Let me make some possibly correct predictions on this basis.

In 2525, people will not get cancer let alone die from it. How much does Gleevec or the like cost per month of additional life? People will be able to travel from point to point on the planet in less than fifteen minutes. You'll notice nothing about the means of such transportation or the necessary scheduling logistics and societal changes necessary to deal with potential bottlenecks. People will only buy travel in the way one buys a book or movie ticket.

Energy use per-capita will be lower than today, but heating, cooling, transportation and manufacturing will be more productive. Manufacturing will increasingly be as-needed to reduce inventory and waste and to track trends more closely. Food will be produced similarly, and I will not predict the end of meat eating as some food production will remain an art form and food production will have very low business entry costs thanks to a broad commons of plant, culture and animal frameworks.

In some ways, society advances one patent expiration at a time.

P.S. The Fermi Paradox is based on a rather naive understanding of probability and of technology. The Drake Equation, for example, simply multiplies probabilities which is not how range estimates are combined. The Fermi Paradox and Project SETI assume that advanced civilizations have nothing better to do than pump EM radiation out in all directions. I, for the life of me, cannot imagine why they would do that. The age of 50KW radio stations is long past.

It seems to me that, with the exception of a few things already mentioned like de-salinization and room temperature superconductors, the areas of scientific progress are likely to be biological rather than engineering/physics. As Graydon keeps pointing out, climate change is likely to have a much more severe effect on food production. That makes it likely that we'll see efforts at genetic modification to account for the new environments.