Good Headline, Disappointing Core Inflation Numbers Þis Morning

Þis is not quite a Goldilocks economy, but it is very, very close to being one.

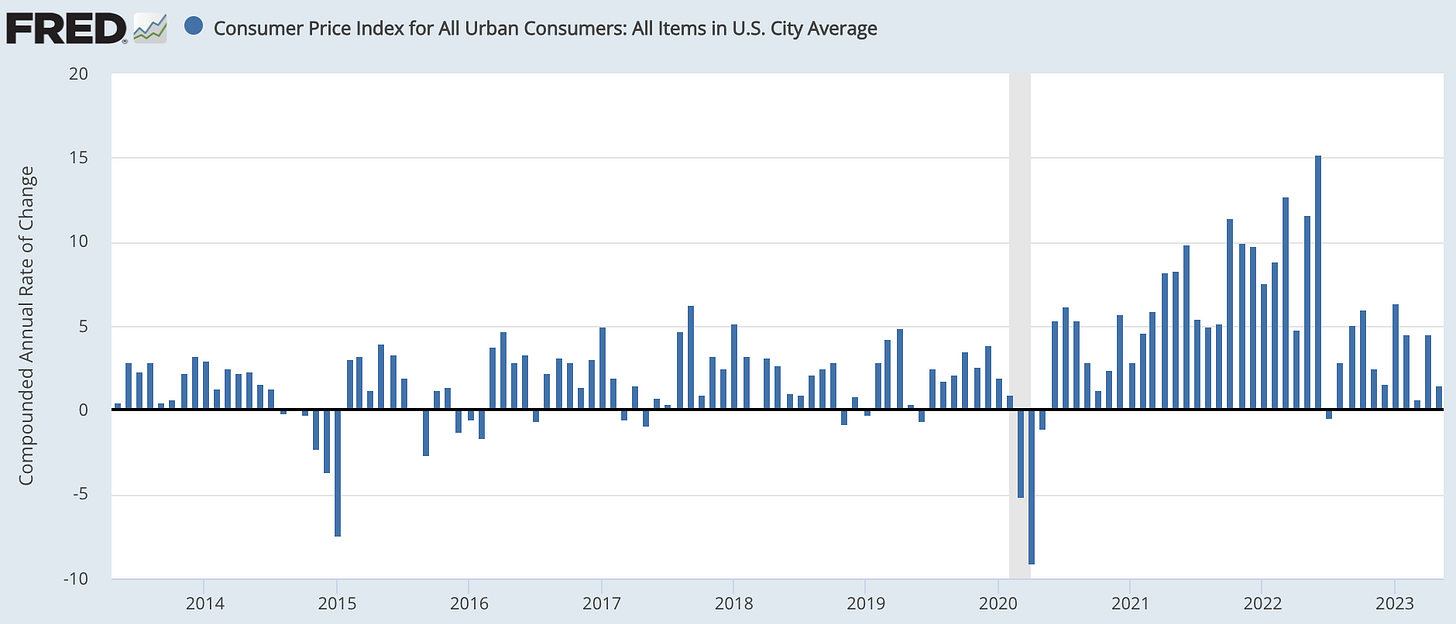

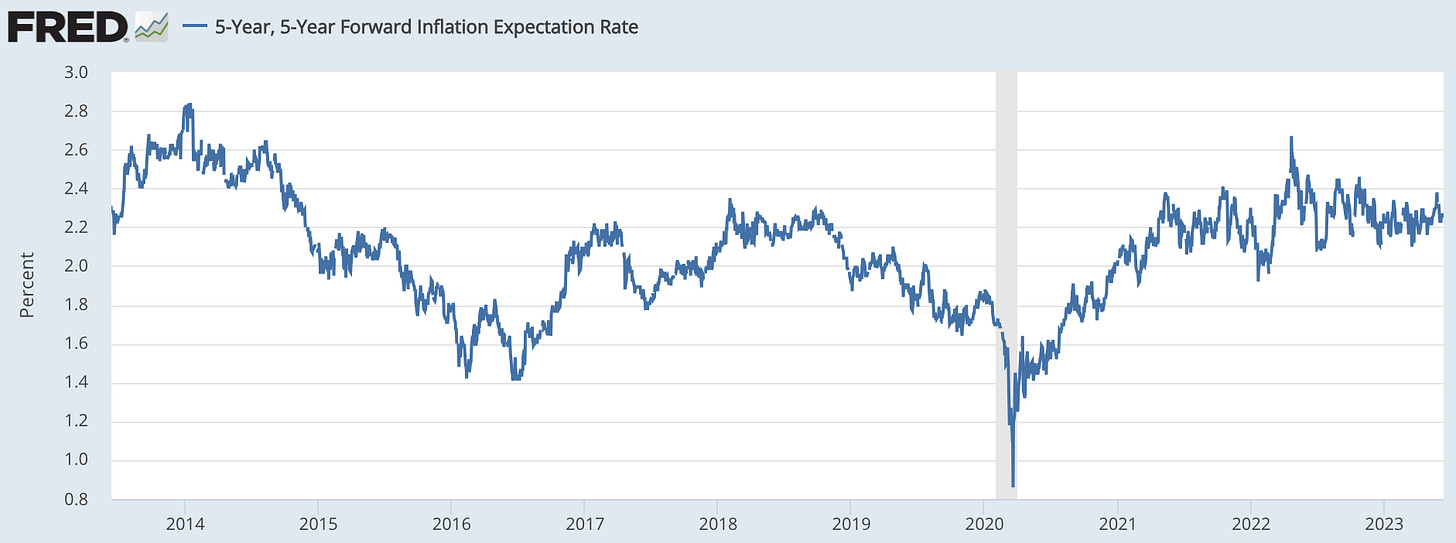

Inflation rates month-by-month for the past decade:

The most recent inflation numbers from the BLS came out this morning, with May CPI inflation depressed to a 1.2%/year rate—far below the Federal Reserve’s 2%/year target:

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics: Consumer Price Index Summary: The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) rose 0.1 percent in May on a seasonally adjusted basis, after increasing 0.4 percent in April, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. Over the last 12 months, the all-items index increased 4.0 percent…

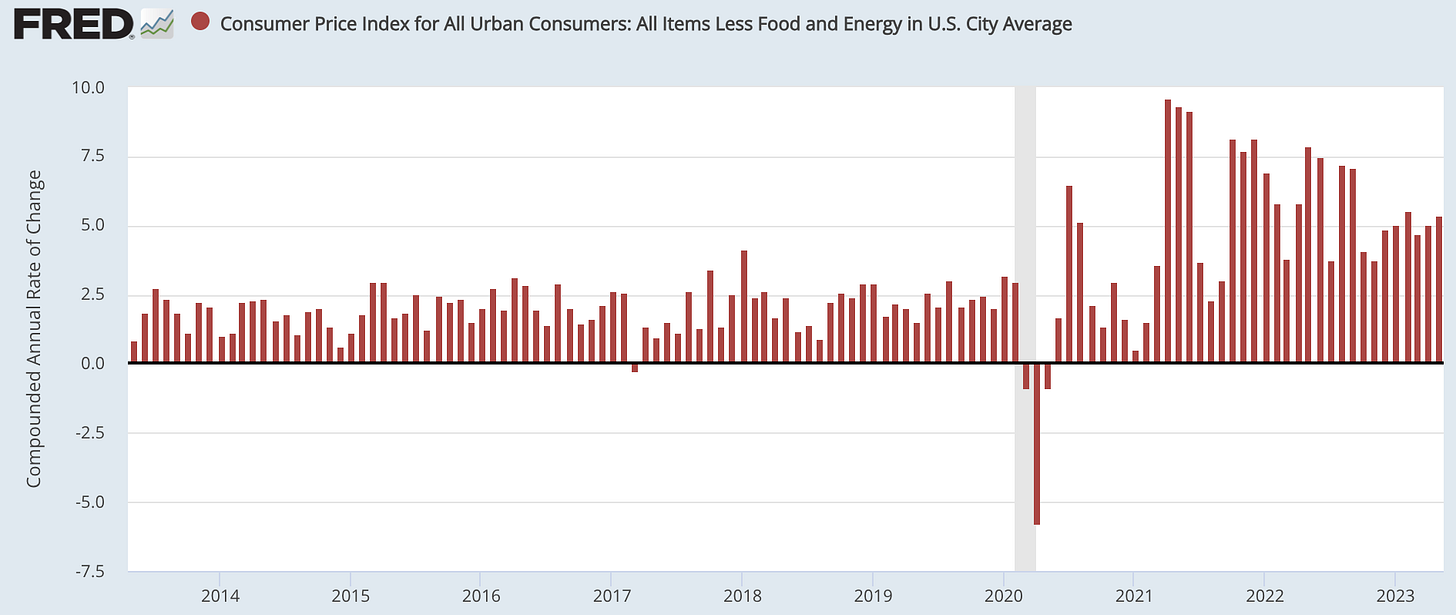

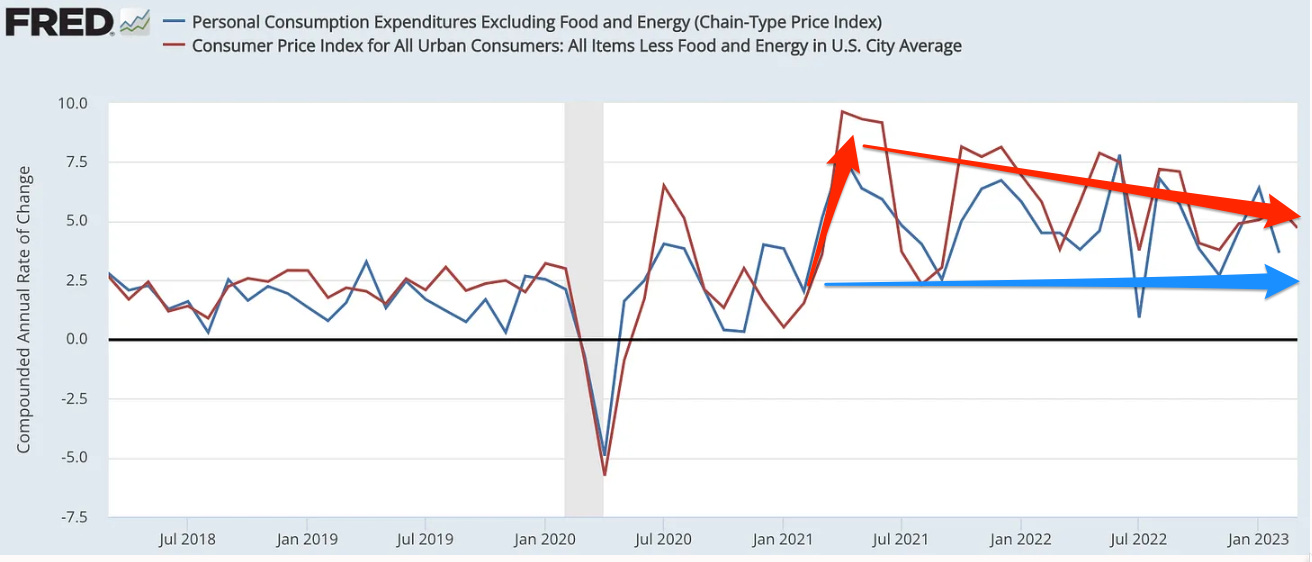

But excluding food-and-energy, standard core CPI inflation was flat: a 5.3%/year annual rate for the month, and 5.3% over the entire past year. Shelter, used cars, and motor-vehicle insurance were all elevated substantially.

If you believe that core inflation is highly inertial—that the best predictor of future core inflation is past core inflation—and that food-and-energy fluctuations return to core, then the economy is still running hot, and to get back to even near the Federal Reserve’s targets will require more slackening of demand to curb pricing power on the part of sellers of both commodities and labor. And you probably should believe that. The question is how much slackening of demand is still in the pipeline, reflecting past Federal Reserve actions and market actions and reactions that have not yet had their full effect on spending.

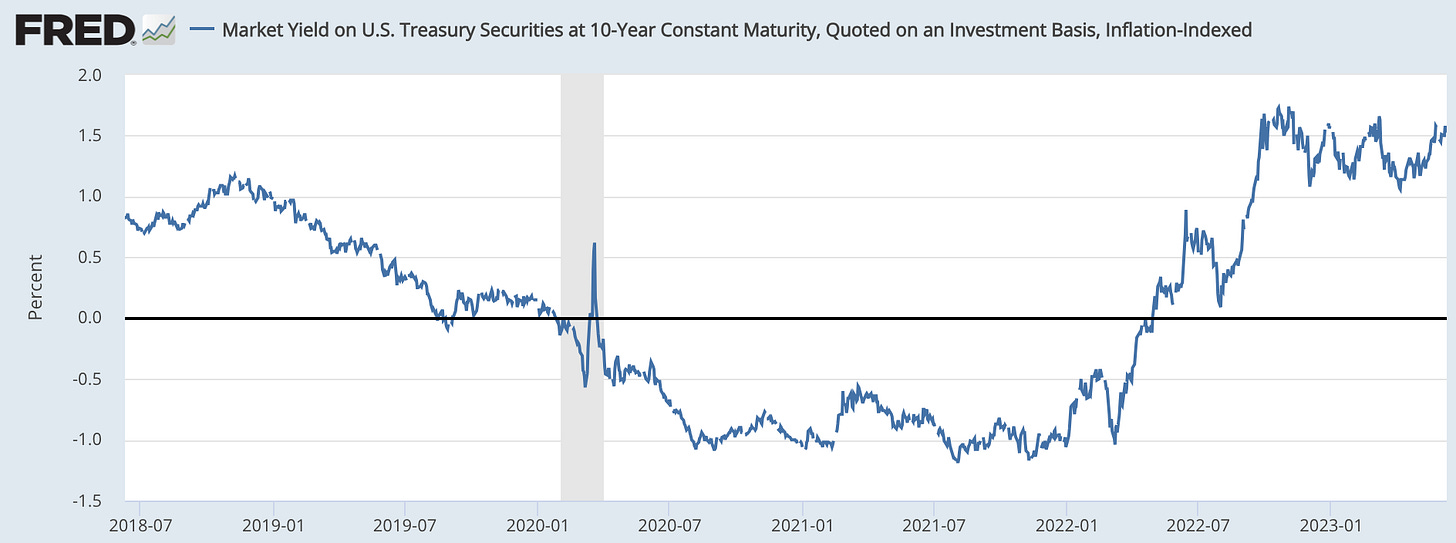

In my view, the best indicator of the real prices people are paying now for rights to cash flows in the future—the slope of the intertemporal price system and thus the incentives people have to invest for the long term and hence to spend money now building up productive capacity—is the US Treasury’s 10-year inflation-protected bond. The chart of its yield is this:

There was a substantial tightening discouraging interest-sensitive investment spending over March-June 2022 of 1.25%-points on an annual basis. There was, later, an additional substantial tightening over August-September 2022 of 1.00%-points on an annual basis. Since then there has been no effective change: the Federal Reserve has since September 2022 what the bond market money thought it was going to do, with expectations being met. The first of these tightenings has, by now, had time to move through the economy and curb spending. The second of these is probably hitting the economy starting now.

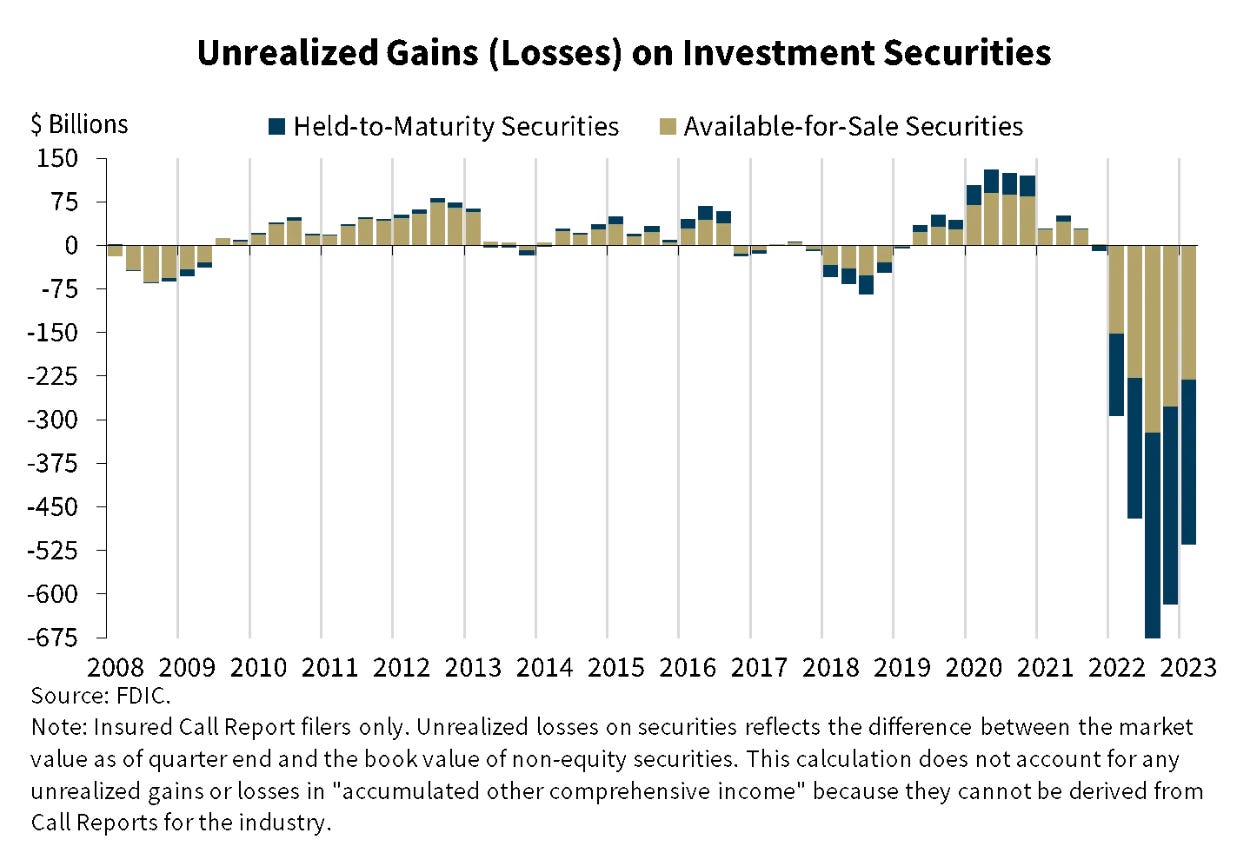

But the price of liquid Treasury bonds on the market does not capture the full state of the bond market. There is always the question of whether you can get a bank to lend to you at all. The spring upset—the failure of three very-large albeit not global-behemoth banks—has made it substantially more difficult to get someone to lend to you. Other banks are reflecting on how those three that failed were taken down by panic triggered by panic at their unrealized losses on investment securities inflicted by the Federal Reserve’s rapid interest-rate increases. Everyone had thought that depositors would be willing to take a long view, and understand that the unrealized losses were overwhelmingly transitory blips that would be reversed for certain for assets held-to-maturity, and would probably be substantially reversed for assets held-for-sale. But that was not the case.

Hence there is now an additional tightening of financial conditions working its way through the economy. How large is this tightening? Is it the equivalent of a rise in interest rates of 0.5%-points, 1.0%-point, or 1.5%-points? Nobody knows.

And the bond market, at least, appears absolutely certain that the Federal Reserve has got this. Its implicit expectation of what inflation will be from five to ten years from now are absolutely rock-solid at a level slightly below one consistent with the Federal Reserve’s target of 2%/year for the PCE (not the CPI!) inflation rate:

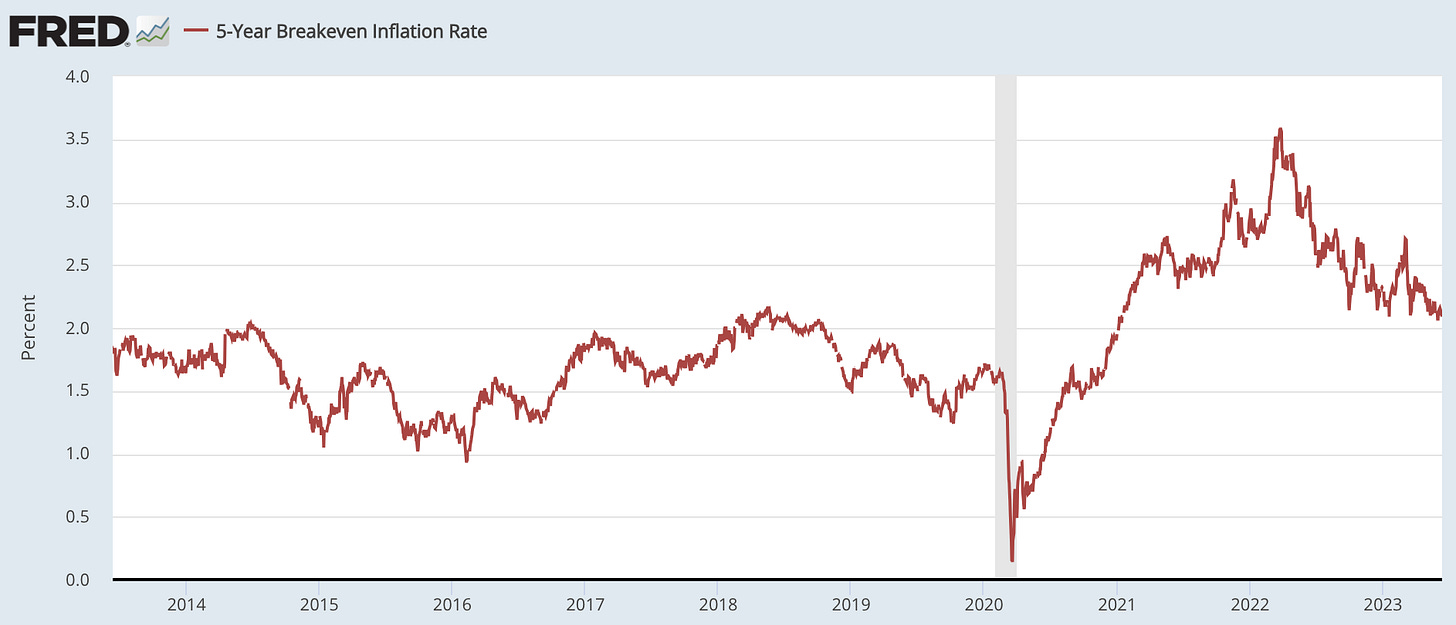

And the bond-market implicit expectation of what inflation will be over the next five years is the same: a hair under the level consistent with the Fed’s target:

All of this put me on Team Pause: The Federal Reserve should note that it has the confidence of the markets, and harvest the value from waiting to act until it has more information about just what the two tightening impetuses still in the pipeline are going to do to the economy. It can, after all, turn on a dime and move far and fast if news comes in that tells it that it is getting behind the curve—either in being caught too loose, or caught too tight, as far as monetary and financial conditions policy is concerned.

And, indeed, the Federal Reserve was strongly signalling that it was going to not “pause” but rather “skip” any interest-rate increase at it’s June 13-14 meeting. And the June 13 CPI Report was read by journalists and markets as reinforcing that semi-commitment:

Reade Pickert: US Inflation Slows, Giving Room for Fed to Pause Rate Hikes: Annual CPI decelerated to 4% in May, slowest since March 2021. Core inflation is still hot, highlighting lingering pressures…

The one downside from the June 13 CPI Report is that it is now a little bit harder to believe that there is an “immaculate disinflation”—a path to return to 2%/year inflation without any material rise in unemployment—than it was last weekend. It is now a little bit harder to believe that the second red arrow will continue:

But that is the only non-silver lining I see.

People like Stanford’s John Taylor see substantial costs to the Fed’s not tightening further now. I confess I do not understand their argument—and here I am not being coy, I seriously do not understand it.

I asked John Taylor about this:

Brad Delong: I agree the Fed moved late and fast, but I do think moving late and fast is optimal… given the asymmetry… imposed by the zero lower bound on interest rates…. I do not see any significant damage… done to the economy by moving late and fast. I see, rather, a benefit in terms of a more rapid reapproach to full employment and getting the von Hayekian crowdsourcing resource allocation… of the market back in gear in a serious way long before it would have happened otherwise…. What is the damage you see to the economy coming from the Fed’s moving late, given that medium and long-term inflation expectations seem to be nailed where they should be, at least according to bond market measures?

John Taylor: I think the main damage is the credibility. The Fed has maintained… two percent for a long time. They [then] let it get as high as 10%. They’re bringing it down… [but] not all the way back to two. That’s for sure.…We have a two percent inflation target. That’s where we should aim for…. The key is to stay with the policy. Maybe [the target] should be higher than two. I don’t think so…. Two is also [the] universal [target]…

I just do not see any damage to the Fed’s credibility.

And the whole point of working to build credibility is that it then gives you policy flexibility in the short run, because you are trusted to maintain effective price stability in the medium and long run. That policy-flexibility running room can then be used for the public good. There is no reason not to take account of it in planning your policy.

You, however, probably want me to give more of a clue as to what is likely to happen to the macroeconomy than I have. You don’t want me to just say: it is uncertain, and so the Fed should wait and see.

So what is likely to happen in the short and into the medium run to production, inflation, and unemployment?

There is the FT-Booth Survey of a panel of economists (which I am on). It came out last Saturday. Let me see if we can divine some wisdom-of-the-crowds from it:

Colby Smith & Sam Learner: Economists forecast at least two more US rate rises to quell inflation: ‘Experts polled by the FT say Fed will need to take tougher action than markets expect to cool economy…. After 10 consecutive increases since March 2022, the federal funds rate now hovers between 5 per cent and 5.25 per cent, the highest level since mid-2007….

Most economists expect the policy rate to peak between 5.5% and 6%…. More than half of the respondents said the peak rate will be achieved in or before the third quarter, while just over a third expect it to be reached in the final three months of the year. No cuts are expected until 2024….

Most of the economists thought the Fed would skip a June move…. Nearly 70 per cent said that doing so would be the right call… and that officials could also resume increases if necessary. “The economy turned out to be much more resilient than we originally thought and the question is: is that resilience temporary and the hikes in the pipeline are sufficient or does the Fed need even further hiking? The Fed is pausing to see if it can get a better read on which of those two is correct,” said Jonathan Parker… [who] is of the view that the Fed will deliver at least two more quarter-point rate rises…. Arvind Krishnamurthy… said… clearly a credit crunch is under way….

Roughly a third of the respondents said it was “somewhat” or “very” likely that core PCE would exceed 3 per cent [at the end of 2024]. More than 40 per cent said it was “about as likely as not”…. Most.. do not expect an imminent, material jump in… unemployment…. The median estimate for year-end stands at 4.1 per cent, slightly higher than its current 3.7 per cent level…

That seems to me to be about right.

My assessment: Things since Biden took office have gone amazingly well. The prime-age employment-population ratio has jumped from 76.4% to 80.7%—a level not seen since the boom of the Clinton-Gore years. There is great hope for a high-pressure economy, which would be optimal support for the market economy and fully enable it to accomplish its von Hayekian task of crowdsourcing solutions to problems of production, and thus making us a much richer country much faster. And even though ex post we might wish for less fiscal stimulus and more monetary restraint in 2021 and early 2022, the actual policy mix bought us valuable insurance against a repeat of the disappointing and inadequate ænemic recovery of the Obama years, and did so with no visible costs that I can see—save three big bank failures, the fallout from which appears to have been well-contained.

Thus in my view the Fed should keep doing what it has been doing. Yes, the past two and a half years have seen a burst of inflation of a magnitude that I found very surprising, much larger than I had expected to see as we came out of the economic depression caused by the plague. But inflation expectations have been and continue to be nailed to what they need to be for the Fed to hit its medium-term inflation target. The relative-price movements—the responses of wages to labor shortage, and of prices to bottlenecks—we have seen since the start of 2001 are strongly, strongly positive-sum. They are necessary if the market economy is to do its von Hayekian crowdsourcing-solutions-to-resource-allocation job. The associated inflation that has accompanied those relative-price movements is zero-sum: it has not been a net loss to the country in real-income terms.

The associated inflation will remain zero-sum unless it feeds through to elevated expectations of medium-term inflation in the future. Such elevated inflation expectations would bring with them a temporary rise the natural rate of unemployment, and so be a substantial loss. But there are no signs of any such shift in medium-term inflation expectations. Thus there are no net downsides—and very powerful upsides—to the policy the Federal Reserve (and the Biden Administration) has followed. So far, Jay Powell and company have got this.

And they have got this even though the supply shock of Putin’s attack on Ukraine have deranged the global economy substantially.

Were they smart or were they lucky?

They were smart insofar as they made a return to pre-pandemic unemployment a priority and repeatedly warned the world of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and unified almost all of Europe in the process against Russia with a combination of sanctions, military intelligence and arms and leadership (supporting the brilliant Zelenskiy) that thwarted to a great extent Russian energy hegemony on Europe. The $30 trillion bond market, the greatest bazaar of behavior and sentiment, reflected these strategic choices which DeLong and Krugman assessed accurately. John Taylor's response is incomprehensible when the bond market is the real time reality check and most legitimate reference of Fed confidence.

You are far kinder to people that keep banging the credibility drum than I would be in this situation.