Guns, Germs, Steel, Coal, Slavery, Seaborne Empires, Peninsulas, Mountain Ranges, Rainfall, & Chance: Jared Diamond's "Guns, Germs, & Steel" After Twenty-Five Years

I am strongly positive on "Guns, Germs, & Steel"; David Kedrosky is even more positive; so let me, against þe grain, try to set out what can be said in critique of Diamond þt is not stupid...

I am strongly positive on "Guns, Germs, & Steel"; David Kedrosky is even more positive; so let me, against þe grain, try to set out what can be said in critique of Diamond þt is not stupid...

Young whippernapper Davis Kedrosky—who we at Berkeley are about to lose to Northwestern—has written a 15,000-word defense of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel <https://www.amazon.com/dp/0393061310> against Diamond’s critics: David Correia, James Blaut, Jason Antrosio, Ned Richardson-Little, Aaron Jakes, Jeffrey Ostler, Thomas Lecaque, and others:

Whenever I have dipped into these and others of Diamond’s critics, I have found myself quickly concluding that for the most part they:

are too lazy to read, or

never learned how to read, or

lack basic discourse ethics.

And often it is not an “or”: it is all three.

Plus there is what C. Northcote Parkinson was the first to label “injelitance”:

incompetence and jealousy… fuse, producing a new substance that we have termed “injelitance”… [an] individual who, having failed to make anything of his own department, tries constantly to interfere with other[s]… this particular mixture of failure and ambition…. He dare not say, "Mr. Asterisk is too able," so he says, "Asterisk? Clever perhaps—but is he sound? I incline to prefer Mr. Cypher." He dare not say, "Mr. Asterisk makes me feel small," so he says, "Mr. Cypher appears to me to have the better judgment."… So Mr. Cypher is promoted and Mr. Asterisk goes elsewhere…

Thus I find that I disagree with very little of what Davis says. It is indeed the case that lots of critics of Diamond, at least in my browsing around, sound, when they are polite, like Aaron Jakes:

Diamond is maligned by historians of colonialism and capitalism because he naturalizes global inequality by a clumsy sleight of hand. He introduces the project as a critique of racial determinism only to replace it with a deeply misleading environmental determinism…. Diamond confuses or conflates “how” questions (of capabilities, mostly of some people to kill others) with “why” questions, which would require something other than the barest conception of “human nature.”…

The book really falls apart at the end…. On the basis of Diamond’s arguments, one would be led to assume that Iraq and Egypt would be among the wealthiest and most powerful countries in the world…. He introduces… absurd speculations about bumpy coastlines…. Diamond can’t or won’t explain… why Europeans crossed the Atlantic in the first place and what they were doing once they arrived…

And I do think Davis Kedrosky does have Jakes’s number here:

Aaron Jakes… dismisses the first 410 pages—“a decent synthesis of existing literature on the historical conditions of differential immunity and technological endowments at the moment Europeans encountered the 'New World”—to focus on pages 409-417…. “Diamond’s arguments… [would] le[a]d [one] to assume that Iraq and Egypt would be among the wealthiest and most powerful countries in the world… absurd speculations about bumpy coastlines.”

[But] Diamond explains the ecological difficulties of the Near East without recourse to “speculations about bumpy coastlines”. Low rainfall meant that plant growth could not keep up with the rate of overgrazing and deforestation; this in turn led to erosion, the silting up of valleys, and salt accumulation. Forests and grasslands became deserts—thanks not to innate characteristics of Middle Eastern farmers, but a common tendency to deplete the environment interacted with a climate that was more sensitive to long-term exploitation (and got worse over time)…

But there are some things that Kedrosky does not say. So let me try to resuscitate the critique of Diamond, contra Kedrosky:

Davis does not include the thoughtful Tim Burke among his critics of Diamond. And Burke has lots to say that is smart:

It is a serious mistake to even imply that Diamond is racist, as Henry Farrell properly observes…. [But] he has a stubborn inclination to use racial terms when they don’t serve any empirical or descriptive purpose…. Diamond clings to the term “blacks” as racial category within which to place most pre-1500 sub-Saharan Africans except for Khoisan-speakers and “pygmies”, even as he explicitly acknowledges that it is an extremely poor categorical descriptor…. Why not call Bantu-speaking societies what they are?…

And:

Diamond has a tendency to… simply bypass… arguments and evidence that don’t fit his thesis…. The Bantu-speaking migration… no question that iron working and farming were very important… the central reason why… pastoralists and hunter-gatherers were either absorbed… or fled…. But Diamond takes it as a given that iron working and farming are sufficient explanation of the migration itself…. He doesn’t even bother to discuss segmentary kinship… and its possible role in pushing expansion. This is the key explanation that many Bantu-speaking societies offer…. When there was… strife or tension… a portion of a lineage would break off behind a charismatic lineage head and move on…

And:

Diamond’s materialism is so confidently asserted and at such a grand scale that he doesn’t even pause to defend it trenchantly the way someone like Marvin Harris does…. There is a tremendous weight of evidence that the general political traditions of the Chinese state plus the particular decisions of its political elite at key moments are much more powerfully explanatory of China’s failure to expand or dominate in the post-1500 era than the big-picture materialism that Diamond offers…

And:

He is a bit prone, like many sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists, to what I think of as “ethnographic tourism”…. You can get away with that when you are just describing a tendency, but the stronger your claims are couched in terms of universality and adaption, the harder it becomes. Diamond is by no means as egregious in this kind of cherrypicking as some evolutionary psychologists are, but the selectivity of his evidentiary citation grates a bit on anyone who knows the ethnographic literature…

Burke is right to note all this.

Diamond talks in an extremely confident and authoritative voice about issues that he does not know well or deeply, and that inevitably grates on the nerves of those who do know the issues well and deeply. This is, inevitably, a big hazard in writing big-think books. It is best guarded against by adopting a much more tentative intellectual stance. But that Diamond does not do. So he starts with one strike—or maybe, given the vanity of professors, two strikes against him.

In the end, one’s assessment of Diamond hinges on what do you think the purpose of the book is:

Suppose you think the purpose of the book is to explain why the Middle East was where most of the action was for most of history, and why Eurasian powers had an enormous techno-military advantage over Australasians, sub-Saharan Africans, and Americans in 1500. Then Diamond does superbly well.

Suppose you think the purpose of the book is to explain why today’s Dover-Circle-Plus societies—those that are in a 300 mile circle around the port of Dover, that have substantial parts of their population descended from migrants from the Dover Circle, or who have strained every nerve to emulate the societies that as of 1500 were found in the Dover Circle—are today so rich, with average annual real GDP per capita levels nine times those of the rest of the world (including the non-Dover-Circle-Plus portions of Eurasia) and 70 times those of the -6000 to 1500 human Agrarian Age Malthusian-poverty norm. Then Diamond has little to say, and does badly.

Pages 1-409 of Diamond are indeed about (1). Only 410-419 are about (2). (Thus the big problem with Jakes is that he focuses on (2) exclusively. Hence Kedrosky’s justified snark about his “just dismiss[ing] the first 410 pages—‘a decent synthesis of existing literature on the historical conditions of differential immunity and technological endowments at the moment Europeans encountered the 'New World’—to focus on pages 409-417”.)

But those remaining few pages are important, even though they are only a trivial part of the writing.

In my view, the big analytical flaw in Diamond is that he does not see that the issues of (2) iares terribly problematic or in need of explanation, given (1). Diamong sees the evolution of global prosperity and inequality after 1500 largely baked in the cake, given the state of things in 1500, as a result of processes that to he who hath, more shall be given. In Diamond’s view, the 1500 technology edge snowballed through the concentration of technological advance in the places where it was easiest, and the technology edge produced massive theft and enslavement because of the human social practice of war, for nearly all humans are descended (in a part of the male line at least) from people who were, very unfortunately, simply too good at this social practice of war.

And in that judgment—and hence in his devoting pages 1-410 to (1) and only 410-419 to (2)—Diamond, I think, committed an error, and hence wrote a substantially suboptimal book.

Even if Diamond is right right in his belief that the gaps in technological prowess between Eurasia and the rest were bound to snowball after 1500 for lots of reasons, that still leaves a question. Why the Dover Circle Plus versus the rest of Eurasia? It is there that Diamond appeals to the “fractured-land hypothesis”—that rapid techno-military-economic advance is produced by a culture area of widespread exchange that is politically fragmented, but not too politically fragmented, like Europe after 1500.

What do we think of this hypothesis of the roots of Western-Eurasian exceptionalism vis-à-vis the rest of Eurasia?

Davis Kedrosky notes the very interesting and thoughtful recent Sng & al. (2022): The fractured land hypothesis: Why China is Unified but Europe is not, which argues that we would expect Western Eurasian political fragmentation (and Chinese and Indian subcontinent unity) from raw geography alone:

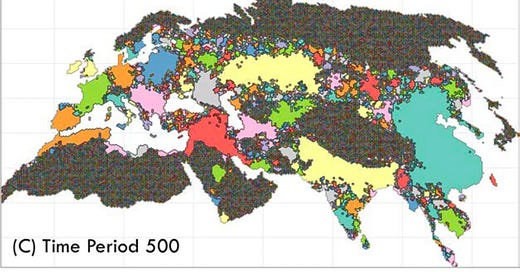

But this figure from their paper strikes me as just too good—we see, recognizably, Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Muscovy, the Habsburg Empire, and the (much earlier period) Neo-Assyrian Empire, as well as China, the Mughal Empire, and the Khanate of the Golden Horde. I smell a specification search, perhaps.

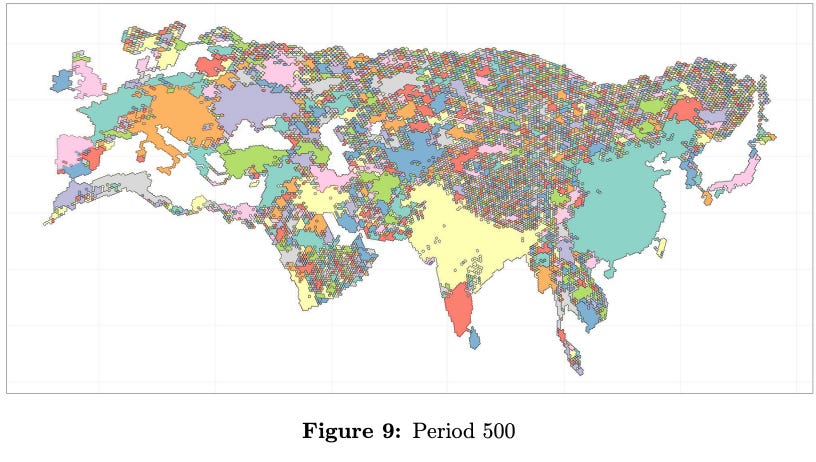

Perhaps a more realistic summary of the strength of their argument can be found in an earlier version than the one published in the QJE, Fernández-Villaverde & al. (2020): The fractured land hypothesis, That earlier version has a different figure:

The lesson I draw from this is: yes, plausible geography-driven (agricultural resources, water communications, and topographical roughness) processes were highly likely to produce Han and Mughal states; yes, the Pyrenees, the Alps, and the English Channel were substantial barriers to political unification; but you cannot really say much more than that.

And, anyway, if cultural unity-political fragmentation is such a boost, why was Europe such a basket case before 1400? As Patricia Crone wrote, very wisely:

Medieval Europe fits the common pattern… a far-flung ruling elite… a cosmopolitan high culture… a myriad of peasant communities… backward in comparison with medieval China, India or the Islamic world, but it was not visibly different in kind…. Post-Reformation Europe fits the pattern too… the only difference being that by now the backwardness had disappeared.

To a historian specializing in the non-European world there is something puzzling about the excitement with which European historians hail the arrival of cities, trade, regular taxation, standing armies, legal codes, bureaucracies, absolutist kings and other commonplace appurtenances of civilized societies as if they were unique and self-evident stepping stones to modernity: to the non-European historian they simply indicate that Europe had finally joined the club…

The Dover-Circle-Plus’s acquisition of a techno-military-political-economic edge is, in one sense, remarkably fast. In 1450 the Dover-Circle-Plus is nothing special. By 1550 its Iberian neighbors have conquered the Americas, have established maritime preeminence over the oceans, and what one might as well call “mercantile capitalism” appears to provide Dover-Circle-Plus societies and their neighbors with an extra degree of societal flexibility for resource mobilization—but are not, outside the Americas, projecting power on land. It is only after 1750 that Dover-Circle-Plus societies have any sort of edge on land in the ultima ratio regum, and can begin to acquire colonial empires in Eurasia and Africa that are more than tolerated fortress-port footholds.

If there was a “fragmentation” edge, where were its effects between 450—when serious fragmentation begins—and 1450?

No. I am not a Diamondian. (And neither is Davis Kedrosky). From 1450 to 1850 I think it is colonies, coal, and cognition that are most important.

Colonies: as Kedrosky writes:

Europe got that ecological relief—horizontally in the form of the New World's land endowment, and vertically, via England's easily-accessible coal reserves…. Europe used slavery and could thus choose the crop mix… but the colonizers would never have been able to deploy slavery without the prior conquest of the Americas…. Following Barbara Solow, Pomeranz argues that free labor was too expensive and Europeans were too poor to pay their own way, so Africans had to be coerced to take their place...

Add to that coal, so that you can build a profitable early steam engine. And add to that a cognition current focused on what is helpful for manipulating nature rather than what buttresses the position of the élite, and you are off and running with the British Industrial Revolution.

But without coal, colonies, and cognition, I think it at least plausible that, as Cosma Shalizi once said, the Malthus-fettered gunpowder empire may have been the climax ecological state of the East African Plains Ape.

And after 1850? Why the post-1850 Great Divergence? As I wrote in my Slouching Towards Utopia:

Robert Allen thinks the dominant factor was imperialism: colonial governments were uninterested in adopting a “standard package”—ports, railroads, schools, banks, plus “infant industry” tariffs in sectors just beyond currently profitable export industries—of policy measures that would have enabled industrialization. Arthur Lewis thought that the most im- portant issue was migration and global commodity trade: indus-trialization required a prosperous domestic middle class to buy the products of the factories, and tropical economies could not develop one…. Joel Mokyr thinks that it was the habits of thought and intellectual exchange developed during the European Enlightenment that laid the groundwork for the communities of engineering practice upon which the North Atlantic core’s industrial power was based. And development economist Raul Prebisch thought that what mattered most were the landlord aristocracies (in Latin America notionally descended from Castilian conquistadores), who thought their dominance over society could best be maintained if the factories that produced the luxuries they craved were kept oceans away. I do not know enough to judge…

And about those questions Diamond has nothing at all to say that is useful.

It's striking how many of the people that criticize Jared Diamond are big fans of David Graeber, which makes you wonder if the debate is really about historical accuracy at all.

Guns, Germs & Steel struck me as an old fashioned geography book, perhaps one from the 1920s or 1950s. These were treatises on geographical reasoning, so they dealt with things like transportation costs and resource availability. The more adventurous of those books would discuss out how geography could shape commerce and society but stayed away from ideas about racial characteristics. A modern critique of these books seems to be that they ignore such racial characteristics as the intrinsic war-like, exploitative nature of Western Europeans. Go figure.

One of the things Diamond did with Guns, Germs & Steel was to get people thinking about geography at a higher level. That's what physicists and chemists do with conservation laws. The energy or atoms have to come from somewhere and go somewhere. You can analyze a black box based on its inputs and outputs, and any imbalance has to be accounted for by a change in state. It can be deeply unsatisfying if you want to understand the details of the mechanism, but you can get useful answers. If you push this in on the top, then that comes out on the side. You can predict the force and velocity, but have no idea of how the black box changes the direction. As I said, this can be deeply unsatisfying, but it is incredibly important and useful. Noether wasn't wasting her time with her theorem.

The Dover Circle empire has its historical precedents, expanding empires driven by technological and institutional change. The Mongol Empire was built on horse based warfare and effective foraging. As with our more modern empire, it had limits, but it conquered a good chunk of Asia. You can look back at the Iron Age empires in the Mediterranean with Alexander as the precursor followed by a more logistically and socially sophisticated Rome. The Incan empire was built on its organizational skills and its control of the highlands. I'm sure someone could find similar patterns in the unification of China. There's more to those stories of standardizing the writing system than imperial whim.

I though Guns, Germs & Steel did a good job of what it set out to do. No, it doesn't even try to explain how the black box turns a downward force into a sideways one, but that was never its point.