HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: 70,000 Years of Human Economic Growth, Briefly

From January 22, 2022:

From January 22, 2022:

70,000 years ago, back in the Early Paleolithic Age, there were perhaps 100,000 of us—100,000 East African plains apes who looked like us, moved like us, acted like us, talked like us, and from whom the overwhelming proportion of all of our heredity is derived. Yes, we have small admixtures (5%?) from other groups and subspecies and maybe even species, but overwhelmingly we are those proto-hundred-thousand's children. Each of them who has living descendants today has a place—has an astronomical number of places—on each of our <http://ancestry.com> family trees. (No, I do not believe that the Khoisan are in any relevant sense “a separate creation”, diverging from those who became the rest of us 200,000 years ago—lots of back-and-forth gene flow over those 200,000 years.)

Back then we were culture-biology co-evolved herd animals. We gathered, we hunted (some), we protected ourselves, we made stone and wood tools, we understood our environment, we manipulated our environment, we communicated with each other, we cooperated and we fought, we talked, and we did the things that humans.

Flash-forward 20,000 years to 50,000 years ago, on the eve or possibly in the middle of our final radiation-migration out of the Horn of Africa and to the rest of Africa, and also across the Red Sea to the wider world. There were then, perhaps, one million of us. We had been very successful in amplifying our numbers, almost surely by crowding our near-cousins out of our common ecological niche in and around the Horn of Africa.

Our standard of living back then? If we had to slot it into emerging-markets standards of living in the world today, we might call it 3.50 dollars a day. Poverty, but not quite what the United Nations calls extreme poverty: natural resources were not scarce, our knowledge of our east African environment was profound, and we probably had to spend a little more than one-third of our waking hours collecting 2000 calories plus essential nutrients each day, plus enough shelter and fire and clothing that we were not unduly wet or cold. We were buff: life was strenuous. But we were short-lived: a life expectancy at birth of perhaps 25-30, for hauling around a family in our then-semi-nomadic lifestyle was dangerous: life was strenuous. And we were in rough ecological balance. The level of our technology? Normalized to our benchmark H(1870) = 1.0, that guessed standard of living and that guess at our then-numbers computes a level H(-48000) = 0.0256 back 50,000 years ago,

Flash-forward another 40,000 years, to 10,000 years ago, on the very eve of the invention/discovery of agriculture and of animal domestication. Things were much the same, save that there were then not one million of us in East Africa but rather perhaps two-and-a-half million of us, well, pretty much everywhere. Our living standards were much the same as they had been. We had better tools, but they were of stone and wood, plus fur and fiber, and not yet metal: it was still the Mesolithic Age. Our knowledge of our environment—or rather environments—was more profound, and so was our power to manipulate them. But in each environment we lived in we found ourselves in rough ecological balance. As of 8000 BC the index H of human technological capabilities stands at 𝐻(-8000) = 0.04.

Over the Paleolithic Era of stone and the Mesolithic Era of stone plus some pottery and textiles from 70 to 10 thousand years ago, the rate at which the stock of useful ideas about technology and organization was growing was 0.001% per year—and, with standards of living stagnant at an average of $3.5 dollars a day or so, the rate of growth of human populations was twice that: 0.002% per year, or 0.05% per generation: a typical generation would see, an average, 2000 people turn into 2001. What if growth over the generations had been much faster? Then, given the—very slow, 0.001% per year—rate of growth in useful ideas H, the population finds itself without sufficient resources to sustain itself and drops. What if growth over the generations had been much slower? The population would find itself better-nourished, with children's immune systems less compromised and women ovulating more regularly, and population growth would have accelerated. Malthusian equilibrium thus kept population growing along with useful ideas, and the rate of growth of useful ideas was very slow.

Then, at the end of the gatherer-hunter age, comes the upward leap (or was it an upward leap) of the neolithic—new stone—revolution. The proportional rate of growth of ideas jumped up, massively, eleven-fold to 0.011% per year, during the -8000 to -6000 Neolithic Revolution: herding and agriculture were really good ideas. 2000 years after -8000 we are (poor) agriculturalists and (unsophisticated) herders of barely domesticated animals, with a human population of perhaps 7 million, but a lower living standard of perhaps 2.50 dollars a day, with an index 𝐻(-6000) = 0.051.

Why a near-tripling of population in 2000 years or so? Because living was easier when you were sedentary or semi-sedentary: you no longer had to carry babies substantial distances, and you could accumulate more useful stuff than you could personally carry. Plus even early agriculture and herding were very productive relative to what had come before. Since life was easier, more babies survived to grow up and themselves reproduce.

Why a fall in the standard of living? Because population grew until humanity was once again in ecological balance, with population expanded to the environment's carrying capacity given technology and organization. But what keeps population from growing further? The fact that life has become harder again. But it became harder in a different way: agriculturalists are shorter—figure about three inches, 7.5 centimeters—malnourished, prone to endemic diseases, and vulnerable to plagues relative to gatherer-hunters. Biologically, it would seem much better to be a typical person in the gatherer-hunter than in the post-Neolithic Revolution agrarian age: your life expectancy is no less, your daily life presents you with more interesting and less boring cognitive problems, and you are much more buff and swole.

Jared Diamond believes—or at least provokes—that the invention of agriculture was, as the title says, a bad mistaker: humans would be better-off had we remained gatherer-hunters.

Technological progress—the discovery, invention, development, deployment, and diffusion of useful and valuable ideas about how to manipulate nature and organize humans—continued at 0.013% per year from -6000 to -3000, the end of the Stone and the start of the Literacy and Bronze Age.In the Bronze and then the Iron Age agriculture, craftwork, organization, literacy, and more advance civilization: from -3000 to -1000, and then from -1000 BC to the year 1, we see H rise at first 0.03% per year, and then 0.061% per year, with a year-1 human population of 170 million. St least half of that year-1 population was collected in three great empires—Roman, Parthian, and Han—enforcing imperial peace, and together spanning Eurasia from what is now Vladivostok to Cadiz and from Hainan to Scotland.

Then comes further development of agriculture, craftwork, organization, literacy, civilization: by year 1 the index 𝐻(1) = 0.25, but our standard of living was not significantly higher, for there were now 170 million of us on the globe.

This is still a Malthusian Equilibrium: vast improvements in technological and organizational capabilities, from 0.4 to 0.43; but all of that improvement going to support a 70-fold increase in human population; and with only 1/70 the potential natural resources at their disposal, the typical peasant or craftsman in 1500 was able to use that technology to eek out roughly the same standard of living as their predecessors 7.5 millennia before.

Now be careful: there is definitely a spurious precision here.

Even if we could gain universal assent as to technological capability in, say, ceramics and each of the other aspects of human productivity and creativity, squashing multi-dimensional objects down into a single one-dimensional index simply cannot be done. All we can say is that if there were an economy simple enough for such an index to be accurate, and if its levels of productivity corresponded to those we assign to the real history, then its index of human technological and organizational capabilities would be our H.

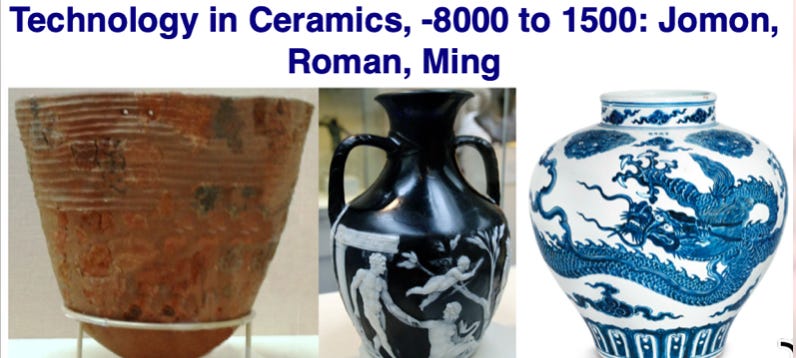

Nevertheless, I find such a framework very useful as a metaphor in organizing my thoughts. The numbers assigned to H do carry meaning. Look at pottery in -8000, in year 1, and in 1500:

John Maynard Keynes, however, would reject that the difference can be measured as quantitative. He said that the idea of doing so is a mistake: that any such quantitative measurement:

is a proposition of a similar character to the statement that Queen Victoria was a better queen but not a happier woman than Queen Elizabeth — a proposition not without meaning and not without interest, but unsuitable as material for the differential calculus. Our precision will be a mock precision if we try to use such partly vague and non-quantitative concepts as the basis of a quantitative analysis…

Mock or not, I find such quantitative estimates useful for organizing my thinking. Queen Victoria does not appear to have been a much better queen than Queen Elizabeth. But, from all historical accounts, Gloriana appears to have been perhaps four times as happy a woman as the Widow of Windsor.

Then from 1—or, rather, from 165 or so—to 800 it looks like we get a definite downshift: the Late-Antiquity Pause. We do not get a further acceleration to more than 0.06%/year of technology growth. We get a fall to a rate of 0.2%/year, a slower rate of technology growth than humanity had seen since before the start of the Bronze Age. Something goes wrong. There is the crisis of the Antonine Dynasty in the Roman Empire at one end, the collapse of the Han Empire at the other end, shortly followed by the collapse of the Parthian Empire and the Indo-Greek kingdoms under pressure a Sassanians, Kushans, Hephthalites, and others.

Instead of the near-tripling from the year 1 to the year 800 in population that the Axial Age of -1000 to 1 would have led us to expect, human population in 800 is less than 40% above population in the year 1. Ideas growth—and population growth—slowed drastically. From 1 to 1500, each person on the globe contributed only 1/6 as much to ideas growth. And it was still the case that essentially all improvements in technology flowed through to increasing population, with essentially none flowing through to higher labor efficiency, productivity, and living standards for the typical human.

The sources of the Late-Antiquity are a substantial mystery, surrounded by speculation, but with little in the way of solid knowledge.

But things then recover, somewhat: 800 to 1500 see technology growth recover to 0.05%/year. So progress in technological advance does, however, continue. By the year 1500 we have 𝐻(1500) = 0.43. But we also have 500 million humans, compared to the 170 million of year 1 or the 7 million of year -6000. Typical standards of living in 1500? They still seem much the same: still 2.5 dollars a day.

Thereafter come the really big changes. Thereafter comes the breakout:

a growth rate of useful ideas of 0.15% per year during the 1500-1770 Imperial-Commercial Revolution Age.

a growth rate of useful ideas of 0.44% per year during the 1770-1870 Industrial Revolution Age.

a growth rate of useful ideas of 2.06% per year during the post-1870 Modern Economic Growth Era.

a population explosion, and then a slowdown toward zero population growth as prosperity brings female education, female education brings greater female autonomy, and literate women with rights to own property find that there are other ways to gain and maintain social power than to try as hard as possible to become the mother of many sons and daughters.

In the speedup from 1500 to 1770 to 1870—over, first, the Imperial-Commercial Revolution and, second, the Industrial Revolution eras—our quantitative index H grows from 0.43 to 0.64 to 1.0. And this time there was some increase in typical standards of living: figure a world in 1870 with $3.50 a day per person, albeit much more unevenly distributed. But, still, the overwhelming bulk of improvements in human technology and organization went to supporting a larger population: the 500 million of 1500 had grown to 1.3 billion by 1870, as better living standards lowered death rates worldwide.

After 1870 came the explosion: from 1870 to 2010, in our era of Modern Economic Growth, our H has risen from 1.0 to 21.5. Our population has risen from 1.3 to 7.6 billion. And our resources from $3.5 to $32 a day: tenfold and more above what it was back in the Agrarian Age. If we have not—as we have not—used our remarkable technological power and wealth relative to all previous human societies to build a utopia, that is on us.

From this perspective, there are two big questions in post-Neolithic Revolution global economic history:

Why was there and what determined the pace of the triple accelerations in growth to 0.15% and then 0.44% and now 2.06% per year?

Why was there and what determined the—much, much, much slower—pace of growth of 0.03% per year (with a -1000 to 1 temporary and with a post-800 perhaps permanent jump up) from the -3000 invention of writing to 1500?

References:

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2022. Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Twentieth Century. New York: Basic Books. <http://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. London: Macmillan. <https://archive.org/details/generaltheoryofe00keyn>.