HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: BioCultural Human Evolution & Its Implications for History & Society

If I do write my "Enlarging the Bounds of the Human Empire..." history-of-economic-growth, I think it will have to have somewhat more human biology than I had thought, or that I am comfortable with...

If I do write my "Enlarging the Bounds of the Human Empire..." history-of-economic-growth, I think it will have to have somewhat more human biology than I had thought, or that I am comfortable with. Will someone either help me down from this ledge, or make me comfortable with the high-wire act that any venture into “sociobiology” requires?

When Melissa Dell teaches the original from which I have appropriated my history of economic growth course, she starts with human evolution. She starts 5 million years ago or so, with the divergence of our lineage from the chimpanzee-bonobo lineage. But I am pretty sure that we do not know enough for it to be worth spending a full week or even half a week on human evolution.

Nevertheless, her reading for that introduction can be read with enormous profit:

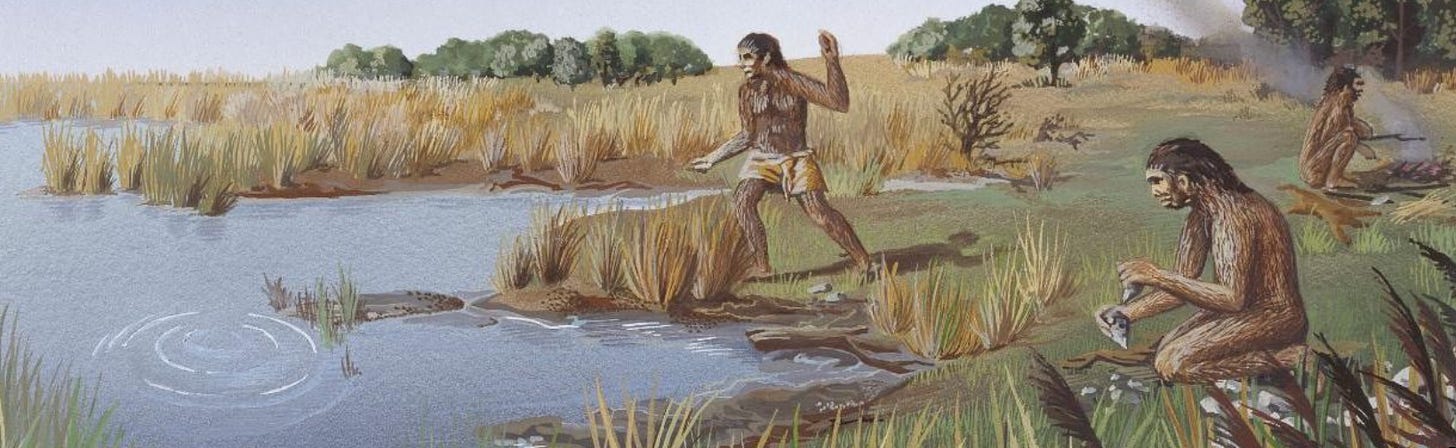

Joseph Henrich (2016): The Secret of Our Success: How Culture Is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter (Princeton: Princeton University Press): Gesher Benot Ya'aqov… 750,000 years ago…. Stone-tool manufacturing… food processing… controlled fire… hand axes, cleavers, blades, knives, awls, scrapers, and choppers… from flint, basalt, and limestone, tool manufacture was done on-site, often from giant slabs carried in from a distant quarry…. Freshwater crabs, turtles, reptiles, and at least nine types of fish… [plus] seeds, acorns, olives, grapes, nuts, water chestnuts… the submerged prickly water lily….

In the next 300,000 years after the activities at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Homo erectus changed sufficiently, including a brain expansion to 1200 cm3, to justify a new species name, Homo heidelbergensis… projectile weapons… a variety of techniques for producing stone blades… consistent within sites or populations but… vary[ing] between populations. Distinct tool traditions and composite tools that exploited natural glues weren’t far behind.….

By 750,000 years ago at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, there’s little doubt that we are dealing with a cultural species who hunts large game, catches big fish, maintains hearths, cooks, manufactures complex tools, cooperates in moving giant slabs, and gathers and processes diverse plants. The bottom line: cumulative cultural evolution is old in our species’ lineage, dating back at least hundreds of thousands of years, but probably millions of years…

And:

Physically weak, slow… dependent on eating cooked food, though we don’t innately know how to make fire or cook…. Our colons are too short, stomachs too small, and teeth too petite. Our infants are born fat and dangerously premature… not so impressive when we go head-to-head in problem-solving tests against other apes….

We are a cultural species. Probably over a million years ago, members of our evolutionary lineage began learning from each other in such a way that culture became cumulative…. Our capacities for learning from others are themselves finely honed products of natural selection…. Cultural learning abilities gave rise to an interaction between an accumulating body of cultural information and genetic evolution that has shaped, and continues to shape, our anatomy, physiology, and psychology…

The history of human evolution is still extraordinarily blurred. Moreover, in my view, very, very, very little of “EvoPsych” results are going to durably replicate. Whatever I would teach about human evolution before 50,000 years or so would, I think, probably be wrong.

Nevertheless, it is very important. So let me set out 10 theses. These are all debatable and disputable. But I think they are worth keeping in mind as likely (ha!) results of our evolutionary history, and as important underpinnings of the economic history of the past 50,000 years:

We are all very very very close cousins. The overwhelming proportion of all of our ancestry comes from one roughly-1000 person or so group 70,000 years ago. Small admixtures from other human groups that were then roaming the world were then added to this mix.

We were human long before 70,000 years ago. People from 10 or 20 times further in the past would in all likelihood be able to fit into our society. Homo ergaster, homo erectus, homo heidelbergensis, homo neanderthalis, homo denisovo, the Red Deer Cave people, and us homo sapiens—and maybe homo floresiensis—are all, in a very real sense, us.

We are cultural-learning intelligences, coevolved biologically and culturally to build up a huge component of our nature-manipulation and group-organization toolkits from observing others of our species, and thus learning the accumulated cultural patterns of past ages.

We are, overwhelmingly, collectively an anthology intelligence: smart not because each of us is smart, but because we can and do learn from, teach, and communicate with others at a furious rate.

We are also a time-binding anthology intelligence: not just us around here who are now thinking, but also our predecessors thinking in the past. That is what gives us our smarts, and allows us to survive.

Since the invention of writing 5000 years ago, the time-binding-ness of our anthology-intelligence nature has been amped up by a full order of magnitude. Our knowledge from the past is not just embedded in present-day cultural patterns, but is also via direct communication from them to us, as we take durable squiggles and from them spin-up and run on our wetware sub-Turing instantiations of the human minds that made the squiggles.

Our intelligence on an individual level is quite limited. We find it very hard to think except in terms of narratives: those narratives usually taking the form of cause and effect, of journeys forward through space, and of sin and retribution, nemesis and hubris. Thoughts that do not fall into those patterns are very hard for us to have, and very very hard for us to communicate to others.

Thus we should not expect our anthology intelligence to get things right. It can get things right in an awesome and mindbending way. But large groups of people can also get things very very wrong and persist in error to a remarkable degree.

Given how incompetent most of us must be in most of the work that our culture has the knowledge to have somebody do, our prosperity—nay, our survival—depends on establishing a cooperative division of labor. We both divide labor and also induce ourselves to cooperate by being primed to form and reinforce social bonds based not on grooming each other to remove parasites (as other monkeys do), and not by mock-mounting each other in para-reproductive activity (as canids do), but rather via forming gift-exchange relationships.

With the invention of money, all of a sudden each of our individual social gift-exchange networks changes from having to be a long-term close-relationship network (limited only to our close kin, our immediate neighbors, and our good friends—and not all of those). All of a sudden our potential division of labor expands to encompass every single other human in the world. This has powerful consequences for us as an anthology intelligence devoted to organizing our selves and manipulating nature.

At some point I recommend reading "Baboon Metaphysics." I may have mentioned it before. It's well outside the range of what you need for your present purposes, or anything you would want to teach, but it is enlightening. Worth making it out of the "read some day" pile and into the "read in finite time" pile. I also enjoyed "Masters of the Planet," particularly the last chapter, but I suspect you've pretty much covered that in other reading, maybe in multiple iterations. The title is rather more triumphalist than the book.

One other thought about gift exchange. Money makes gift exchange possible on a much wider scope, and also violates the limit (about 150) of relationships that any individual can track. Which contributes, it seems to me, to atomization and alienation. The internet has depersonalized this even more. When a retailer doesn't look the customer in the eyes at the checkout, they seem to be a lot more willing to pull shenanigans.