I always wish I had done something more with this...

Richard Evans (2000), Lying About Hitler: History, the Holocaust, and the David Irving Trial (New York: Basic Books: 0465021522).

Richard Evans (1997), In Defense of History (New York: Norton: 0393319598).

The Irving Case

For about a decade Richard Evans's (1987) book Death in Hamburg: Society and Politics in the Cholera Years 1830-1910 had been on my "read someday" list. But at the beginning of 2000 I ran across his name again. He was to be an expert witness for author Deborah Lipstadt in her defense against David Irving's charge that she had libeled him by calling him a "Holocaust denier."

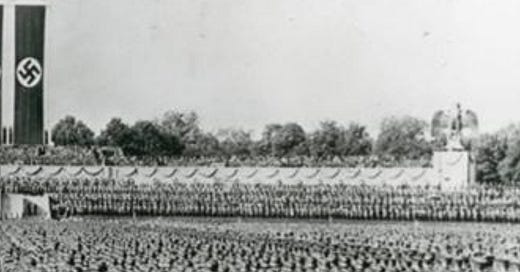

Irving had sued Lipstadt because her 1994 book Denying the Holocaust, had called him a "discredited" historian with "neofascist" connections, an ardent admirer of Hitler who "on some level... seems to conceive himself as carrying on Hitler's legacy," who skews documents and misquotes evidence to reach historically untenable conclusions in the interest of exonerating Hitler (see Evans (2000), p. 6). Irving demanded that Penguin Books, Lipstadt's publisher, withdraw her book from circulation. Penguin refused. And in the summer of 1996 David Irving sued.

Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books then had two choices: (a) withdraw the book and apologize to Nazi sympathizer David Irving, or (b) defend themselves. And, as Richard Evans explains, under British law a libel defense amounts to a no-holds-barred, fangs-bared, go-for-the-jugular attack on the reputation of the plaintiff. As he writes (Evans (2000), p. 193): "[A] successful libel defense... has to concentrate... on massively defaming the person and character of the plaintiff, the only restriction being that the defamation undertaken in court has to be along the same lines as the defamation that gave rise to the case in the first place, and that it has, of course, to be true." Thus the structure of the case: if she were to escape an adverse judgment, Deborah Lipstadt's attorneys had to demonstrate that David Irving was a Holocaust denier who skews documents and misquotes evidence. In short, they would have to demonstrate that he was "discredited": not a credible historian at all.

It was here that Evans was brought in as an expert to provide an assessment of Irving's work as a historian. He agreed to serve as an expert witness at least in part because he was deeply concerned with what makes a historian: Evans had recently (1997) published a book, In Defense of History, that had wrestled with the question of what historians did, and how they did it.

Irving and His Defenders

Irving argued that, even though his politics were unpopular and his historical researches had distressed the Jews and their allies, he was a reputable historian with a reputation to protect against slander and libel. And Irving did have his defenders. After Irving lost the trial, diplomatic historian Donald Cameron Watt believed that Irving's work had been subject to excessive scrutiny and held to an excessively high standard: "five historians with two research assistants... querying and checking every document cited in Irving's books." "Show me one historian," Watt demanded, "...who has not broken into a cold sweat at the thought of undergoing similar treatment." On the witness stand Watt asserted that "there are other senior historical figures... whose work would [not] stand up to this kind of examination" (see Evans, 2000, pp. 245-6).

Watt argued that the active shaping of one's views and interpretations of the past by one's present politics did not keep one from being a historian, and even a great historian: "Edward Gibbon's caricatures of early Christianity... A.J.P. Taylor," and others clearly "allowed their political agenda... to influence their professional practice," like Irving. Military historian John Keegan agreed: Irving had "many of the qualities of the most creative historians" and "has much that is interesting to tell us." In Watt's view, "only those who identify with the victims of the Holocaust disagree" with the proposition that Irving is a reputable historian. And, in Watt's view, Irving's critics are not primarily concerned with pointing out flaws in his historical writings but with stoning a heretic: "for them Irving's views are blasphemous and put him on the same level of sin as advocates of paedophilia" (Evans, 2000, pp. 244-6).

Keegan writes that Lipstadt is “dull as only the self-righteously politically correct can be”, that “few other historians had ever heard of her before this case”, and that “most”—definitely including Keegan—“will not want to hear from her again.” And Keegan clearly and strongly regrets that his testimony at the trial played a “part in [Irving’s] downfall”—in short, that it is a damned shame that Irving did not win his case, and that Deborah Lipstadt’s book was not pulped and she was not rendered bankrupt. And Donald Cameron Watt seems to want to convince his readers—and pretend to himself—that the case was not about Irving trying to get Lipstadt’s book pulped, but rather Penguin Press trying to get Irving’s book suppressed, and that that was bad because “history needs David Irvings”: “Penguin was certainly out for blood…. The worst outcome… could be to drive the Holocaust denial school back into the depths from which Irving ‘outed it’…. truth needs an Irving's challenges to keep it alive.”

Evans would not disagree that many historians throughout the ages had shown themselves to be biased and negligent, and had let their political agenda shape their history. Evans wrote (Evans, 2000, pp. 261-2) of visiting Washington D.C.'s Holocaust Museum and being:

"...struck by its marginalization of any other victims apart from Jews, to the extent that it presented photographs of dead bodies in camps such as Buchenwald or Dachau as dead Jewish bodies, when in fact relatively few Jewish prisoners were held there. Little attention was paid to the non-Jewish German victims of Naziism... the two hundred thousand mentally and physically handicapped... the thousands of Communists, Social Democrats, and others.... The German resistance received almost no mention at all apart from a brief panel on the student 'White Rose' movement during the war, so that the visitor almost inevitably emerged from the museum with a belief that all Germans were evil antisemites..."

What Do Historians Do?

Indeed, it is hard to see how anyone could write a history that was not informed by their current political agenda, or make leaps of interpretation or judgments about sources that would strike others as highly strained or worse. For nearly two centuries the touchstones of the historian's task have been those of Leopold von Ranke: to relate the past "wie es eigentlich gewesen"--how it essentially was (see Ranke, 1981); and not to cram the past into categories that make sense only in the present, for "every age must be regarded as immediate to God" (Ranke, quoted in Fritz Stern, Varieties of History). But we don't know how it essentially was: we weren't there. And it is not enough to simply present the documents and records we have: they only give us knowledge of the skeleton, not the whole animal. So a historian must recreate the past, must imagine it. As Evans (1997, pp. 21-22) summarizes George M. Trevelyan, history was "a mixture of the scientific (research), the imaginative or speculative (interpretation), and the literary (presentation).... The historian who would give the best interpretation of the Revolution was the one who, 'having... weighted all the important evidence... has the largest grasp of intellect, the warmest human sympathy, the highest imaginative power...'"

Thus in doing his or her job a historian must go beyond the bounds that his or her sources prescribe. Consider one of the first historians, Thucydides the Athenian, who wrote the history of the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta at the end of the fifth century B.C. With respect to the narrative of events, Thucydides says that he did not "...derive it from the first source that came to hand" or even "...trust my own impressions, but it rests partly on what I saw myself, partly on what others saw for me, the accuracy of the report being always tried by the most severe and detailed tests possible. My conclusions have cost me some labour from the want of coincidence between accounts of the same occurrences by different eye-witnesses, arising sometimes from imperfect memory, sometimes from undue partiality for one side or the other."

However, Thucydides relates not just the events but many of the speeches of commanders and politicians, "...some [of which] were delivered before the war began, others while it was going on; some I heard myself, others I got from various quarters..." In all cases it was "difficult to carry them word for word in one's memory." So in the History of the Peloponnesian War the speeches are, Thucydides says, "what was in my opinion demanded of them by the various occasions, of course adhering as closely as possible to the general sense of what they really said."

What, then, is the status of a passage from the Peloponnesian War like Pericles's "Funeral Oration"? It is a combination of what Thucydides and his other sources remember Pericles having said, mixed with what Thucydides thinks it would have been appropriate for Pericles to have said, all shaped by Thucydides's own view of what was important about Athens and its empire at the start of the war.

Or consider Ronald Syme's book, The Roman Revolution, which I at least think is the greatest of all historical accounts of the rise and reign of the Emperor Augustus. Written in the 1920s, it clothes the bones of the historical record with the flesh of... Mussolini. It tells the story of the rise of Augustus seen as a fascist dictator, exploiting his material and patronage resources, adding to them lies, propaganda, and a good dose of terror, and emerging as top dog surrounded by sycophantic admirers and conspiring would-be successors.

The Roman Revolution is not a book that could have been written before the 1920s. Until we had seen Mussolini, it was not possible to use the example of Mussolini's rise to and exercise of power to fill in the wide, wide gaps our sources leave in our knowledge of the creation of the Roman Empire. The Roman Revolution is not history as it essentially happened: Augustus in 30 B.C. was almost surely not as close a copy of Mussolini 1950 years later as Syme maintains. But The Roman Revolution is surely closer to history as it essentially happened than the depiction of Augustus as pater patriae and wise demigod presented by his sycophants, or the standard picture of Augustus as a wise nineteenth-century British gentleman, statesman, and empire builder. And it is a superb book.

Or consider the examples raised by Donald Cameron Watt: Edward Gibbon and A.J.P. Taylor. A.J.P. Taylor set out to write the Origins of the Second World War as if Hitler were an eighteenth-century king who aimed at reversing the (limited) results of the last (limited) war: a portrait of Hitler as, as John Lukacs phrase, like the Empress Maria Theresa maneuvering to recover the lost province of Silesia. All evidence that Hitler was something else is thrown overboard, or ignored completely.

Now Taylor's history is not history as it really happened. All you have to do is glance an inch beyond the frame of Taylor's picture--at Nazi domestic policy and the Night of Broken Glass, or at Hitler's conduct of World War II--and you find events grossly and totally inconsistent with Taylor's portrait of an opportunist looking for diplomatic victories on the cheap. Taylor's Hitler would never have widened the war by attacking the Soviet Union and declaring war on the United States, or weakened his own military resources by exterminating six million Jews, four million Russian prisoners of war, and millions of others rather than putting them to work in the factories making tanks and ammunition. Nevertheless, you can learn a lot from Origins...

Edward Gibbon set out to write the story of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire with two purposes: to tell a good story, and to provide a lesson for the future of the danger of barbarism and religious fanaticism. Donald Cameron Watt refers to Gibbon's "caricature of early Christianity" as history not as it really happened but instead molded by Gibbon's own--Enlightenment, tolerant--political agenda. It is not clear to me that Gibbon's picture of early Christian bishops and theologians is a caricature. The council of Nicaea seems to caricature itself quite well, for there the bishops and theologians proclaimed that anyone having trouble understanding the phrase "eternally begotten" could mean was condemned to hell. Such behavior seems profoundly... un-Christian. Gibbon focuses on theologians who played intellectual dominance games and on bishops who played power games rather than on saints or believers seeking to live holy and just lives. But there were such theologians and bishops (just as there were saints and believers).

So how can Evans draw a bright, distinguishing line between historians like Thucydides, Syme, Taylor, and Gibbon--more-than-reputable historians, great historians--all of whom go beyond the boundaries of their evidence in one way or another, and David Irving?

Irving and His Sources

But Evans has a response: that what makes Irving "discredited" is not the imaginative interpretations he builds on top of the historical evidence he has found, but instead his--mendacious--handling of the evidence itself. In his evidence before and at the trial, Evans focused on a very basic question: Does Irving tell the truth about what his source materials say, or does he lie about them? Evans's answer was that Irving did not tell the truth, that he did habitually lie, and so he was not a historian at all. Let me cite three of Evans's examples.

A first example, found on pp. 49-51 of Evans (2000), is Irving's claim that when the Nazis came to power many German Jews were criminals: "In 1930 Jews would be convicted in 42 of 210 known narcotics smuggling cases... 69 of the 272 known international narcotics dealers were Jewish... over 60 percent of... illegal gambling debts... 193 of the 411 pickpockets arrested..." But Irving's source turns out of be SS General Kurt Daluege, a Nazi party member since 1926 who had joined the SS in 1930. Irving had used, as Evans says, "antisemitic propsaganda by a fanatical Nazi... as a statistical source for the participation of German Jews in the Weimar Republic in criminal activities." These numbers are "utterly useless" and are radically inconsistent with the fact that only one percent of so of prison inmates were identified as Jewish.

Second, consider Irving's summary views of Adolf Hitler, quoted on pages 40-41 of Evans (2000):

"Adolf Hitler was a patriot--he tried from start to finish to restore the earlier unity, greatness, and splendour of Germany. After he had come to power in 1933... he restored faith in the central government; he rebuilt the German economy; he removed unemployment; he rebuilt the disarmed German armed forces, and then he used this newly-won strength to attain Germany's sovereignty once more, and he became involved in his adventure of winning living-space in the East. He has no kind of evil intentions against Britain and its Empire, quite the opposite.... Hitler's foreign policy was led by the wish for secure boundaries and the necessity of an extension to the east.... The forces which drove Germany into the war did not sit in Berlin."

This clearly will not do. The forces that drove Germany into the war did sit in Berlin: Hitler attacked Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Holland, Luxemburg, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Russia, after all. Britain might (but might not) have been able to stay out of the war had the British government not sought even at the risk of war to protect other peoples from Nazi rule and preserve the balance of power in Europe--but there would have been war in any event. Moreover, the phrases "necessity of an extension to the east" and "adventure of winning living-space" are deeply mendacious: they cover Hitler's plans for the large-scale ethnic cleansing of Poland and the Ukraine and the demographic replacement of their existing populations by ethnic Germans with a likely resulting civilian death toll of more than fifty million. In Hitler's plans the Holocaust as we know it was merely an appetizer. Had the Nazis won the war on the Russian Front we would have seen the main course.

A third example, found on pages 62-63 of Evans (2000), is Irving's handling of the documentary record surrounding the Nazi pogrom of "the Night of Glass" in 1938. The source is the diary of Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels. As Evans writes:

"Goebbels... reported on it in his diary on 11 November.... 'I report to the Fuehrer at the Osteria. He agrees with everything. His views are totally radical and aggressive. The action itself has taken place without any problems. 17 dead. But no German property damaged. The Fuehrer approves my decree concerning the ending of the actions, with small amendments. I announce it via the press and the radio. The Fuehrer wants to take very sharp measures against the Jews. They must themselves put their businesses in order again. The insurance companies will not pay them a thing. Then the Fuehrer wants a gradual expropriation of Jewish businesses.' This entry clearly suggested to me, as it would surely have done to any historian with an open mind, first, that Hitler approved of the pogrom, and second, that it was Hitler who devised some of the economic measures ordered against the Jews...."

But what does Irving do with this material? Evans provides three quotes from Irving, one from 1992: "according to [Goebbels's] diaries, Hitler was closely implicated with those outrages.... I have to revise my own opinion. But a historian should always be willing to revise his opinion"; one from 1993: "'[w]ait a minute, this is Dr. Goebbels writing this.' Dr. Goebbels who took all the blame for what was done. So did he have perhaps a motive for writing in his private diaries subsequently that Hitler endorsed what he had done? You can't entirely close that file"; and one from 1996, by which time "...Irving had... a total conviction that Goebbels was lying... not influenced by any further discoveries of new documentary material" (Evans, 2000, pages 62-63).

Indeed, Evans found that Irving's misinterpretations were remarkably obvious, and his embrace of Nazi rhetorical modes remarkably complete. Irving is a man who refers to Jews as "our traditional enemies." He speaks of "the Jewish ghettos of Great Britain." He attacks the "odd and ugly and perverse and greasy and slimy community of "anti-Fascists" that run the very real risk of making the world fascist respectable by their own appearance!" He has prophesied that American Jews' "moving in to the same positions of predominance and influence (media, banking, business, entertainment, and the more lucrative professions like law, medicine and dentistry) that they held in Weimar Germany" would lead to a rise of Nazism in America in twenty or thirty years (Evans, 2000, pp. 136-7).

And near the end of the trial he addressed the presiding judge as "Mein Fuehrer" (Evans, 2000, page 224).

Evans thus concluded that Irving was not just a bad historian whose mistakes were due to "negligence... random in its effects," but not a historian at all: "all the mistakes... in the same direction... deliberate manipulation and deception" (Evans, 2000, page 205). That was, for Evans, the touchstone. In Evans's mind historians should not be negligent, and they should not be biased: "...there have been too many cases in the past of historians selecting and suppressing evidence." But the one thing they could not do and remain historians was to deliberately lie about what the historical evidence said (Evans, 2000, p. 247). His overwhelming fascist sympathies and what he had done to try to get people to accept them meant that Irving's work simply could not be trusted: as Hugh Trevor-Roper put it politely, whenever Irving was most original he was least reliable.

Conclusion

So I believe that Richard Evans and the other witnesses called by the attorneys for Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin proved their case: the assertions about Irving made in Denying the Holocaust were substantially true. Her book would not be suppressed in Britain. According to Evans's categorization--with its stress on being a truthful voice of the documents and other primary evidence--Irving was not a historian at all, or not a very good historian. (Of course, it is hard to see how A.J.P. Taylor can maintain his reputation in Evans's eyes, given various passages sin Origins of the Second World War.)

In Evans's view, a historian is a member of and a participant in an ongoing discourse that grounds itself most firmly in the available primary sources. Arguments between historians are believable and effective to the extent that they are rooted in credible and genuine sources. The imaginative structure of interpretation--the flesh that clothes the primary-source bones--is important, but energy, ingenuity, and creativity in interpretation cannot offset a weak base in what the sources actually say.

But is this enough? Don't we actually demand more of a historian? Don't we demand not just that a historian accurately represent his or her primary sources, but that the primary sources he or she relies on be the most important or the most interesting or the most typical ones?

Moreover, doesn't the interpretive structure built on the primary sources have to be convincing, psychologically plausible, and accessible to the reader as well? Ronald Syme's Roman Revolution is a success not just because it uses (and uses well) the bulk of the (little) primary source information we have, and because we finish the book thinking that was how it well could have been. Thucydides... well, we really do not know how good a historian Thucydides was, because we cannot challenge his judgments and emphases. But we do know that he worried about the right questions of how to achieve as accurate an account as possible. Gibbon... we today read Gibbon as a work of literature, not of history. And A.J.P. Taylor's Origins of World War II is ultimately a failure because its psychological picture of Hitler's motivations and aims is inconsistent with what else we know about Hitler from primary sources outside the book.

So it seems to me that ultimately Evans's attempt to draw a bright line between Irving and the historians fails. When Watt worries that the forces unleashed by the Irving trial will impinge on the reputation of historians like Gibbon and Taylor who "allowed their political agenda... to influence their professional practice," and who used the available primary evidence selectively and tendentiously, he is right: it will. Misquotation and mistranslation are greater sins against Clio than merely averting one's eyes from pieces of evidence, or telling history to make a particular point rather rather than as it really happened. But they are not the only sins.

And how did Watt and Keegan react to the verdict of the trial? They seemed to react by lashing out. Watt wrote of how "[p]rofessional historians have been left uneasy by the whole business" (Evans, 2000, p. 246). Keegan denounced Lipstadt "as dull as only the self-righteously politically correct can be. Few other historians had ever heard of her before this case. Most will not want to hear from her again." They spoke as if they would have preferred it had Irving won his case.

Evans writes, "I had to pinch myself" in order to remember that it was Irving who "...had launched the case... was attempting to silence his critics... wanted a book withdrawn... and pulped... [demanded to be paid] damages and costs, and undertakings given that the criticisms... of his work should never be repeated" (Evans, 2000, p. 27).

Evans quotes Neal Ascherson, who asked why Watt and Keegan saw the trial's outcome--the failure of the judge to grant Irving's demand to suppress Lipstadt's book in Britain--"as a form of censorship, a clamp on the limits of historical enquiry." Ascherson observed that "both see Irving as still somehow 'one of us'--wrong but romantic. But Lipstadt is a respectable historian too, more honest in her use of documents than Irving, and the trial vindicated what she said about him. So why is she being slighted as somehow not quite one of us?" (Evans, 2000, p. 252). Evans observes that Ascherson, "perhaps wisely," did not answer his own "rather disconcerting question." Evans does not answer it either. But the answer seems obvious: Deborah Lipstadt is female, American, and Jewish. How could men like Watt and Keegan ever regard her as "one of us"?

Other references:

John Keegan (2000), "The Trial of David Irving--and My Part in His Downfall" http://abbc.com/aaargh/fran/polpen/dirving/dtjk000412.html

Leopold von Ranke (1981), The Secret of World History: Selected Writings on the Art and Science of History (ed. Roger Wines) (New York, 1981).

Fritz Stern (1973), Varieties of History (New York: Random House).

Also at: <https://github.com/braddelong/public-files/blob/master/review-evans-lying-about-hitler.pdf>

<https://braddelong.substack.com/p/reading-review-of-richard-evans-lying>

I know this is a year old, Brad, but I was glad to come across it as I was searching for Watt's comments. I vaguely remembered them from reading about the trial years ago, and I was sort of boggled by Watt's attitude. "C'mon, you guys, you can't expect our footnotes to actually support our arguments. That's not how history works." Ah! Well, good to know!

I was prompted to search by the current brouhaha over Claudine Gay's resignation. There seem to be a number of academics defending her failure to enclose various passages in quotation marks. I agree that some of her plagiarism is trivial, but some of it isn't. There have been a few rumblings that chime with Watt's, comments along the lines that if you subjected every academic to a plagiarism checker, *many* would fail. Is this a case of "saying the quiet part out loud", or is it simply a few bad actors projecting their own misdeeds onto academia as a whole? The sociology of academia is fascinating.