HOISTED FROM THE ARCHIVES: Why you should be happy about inflation and worried about something else, top economist Brad DeLong says

Tristan Bove's "Fortune" article from 2022-09-17

How could high inflation possibly be good?

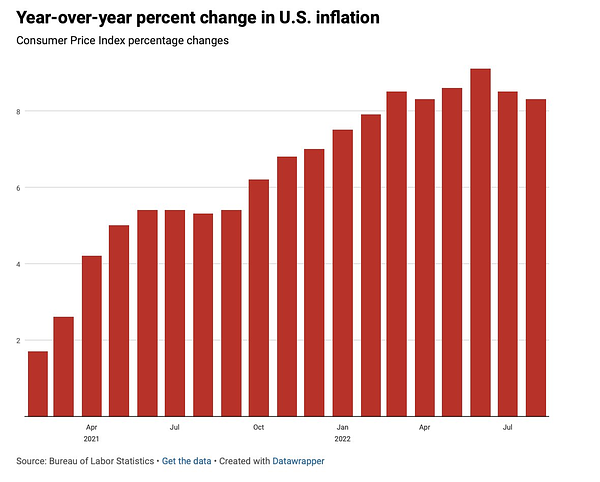

Not only are you paying more for stuff than a year ago, but the consistently higher-than-expected readings in the Consumer Price Index continue to devastate the stock market, sending the S&P 500 down over 1,000 points on Tuesday, its worst day since June 2020.One of America’s top financial historians says this moment calls for a lesson in economics.

“The reopening inflation we’ve had has so far been a very good thing,” Brad DeLong, a professor at UC Berkeley, told Fortune. His comments contradict the more hawkish stance on inflation famously championed by Harvard economist Larry Summers, who worked alongside DeLong in the Department of the Treasury during the Clinton administration.

DeLong argues that there is a major economic shift taking place that people should welcome. It all has to do with our strange but kind of wonderful post-pandemic economy.

The new economy, DeLong says, is one with more time spent online, fewer jobs requiring in-person interactions, and a substantially higher rate of goods production.

It’s like we have zoomed decades into the future in just a few years.

“A couple of decades,” DeLong said when asked about how many years of economic change have been crunched into just over two: “A couple of decades of structural change and social and economic learning about how to be online as a permanent thing.”

“Fewer in-person workers in retail establishments, a lot more delivery orders, substantially more goods production, and also substantially more information entertainment and production as well,” is how DeLong described his vision for the new economy during a separate interview with Fortune last week covering his new book, Slouching towards Utopia. The meeting took place over Zoom, DeLong noted, proving his point.

Inflation in the U.S. is currently serving two functions that could help the economy in the long run, according to DeLong: helping expand new economic sectors poised for big growth, and uncovering and optimizing supply chain snags that have been with us since the beginning of the pandemic.

Unemployment is now at its lowest point since before the pandemic, but the full employment we are returning to is not the same as the one we left behind in 2020, DeLong said.

“We want to get back to a full employment economy quickly. But it’s a very different full employment economy when we get back there,” DeLong said.

Moving workers away from industries like retail and hospitality and into expanding sectors needs to come with incentives in the form of higher wages, according to DeLong, which means inflation.

“If you want to create economic incentives for people to move into the expanding sectors where we actually need more workers, their wages have to go up,” he said.

“When you’re coming out of a big recession, the natural rate of inflation has got to be above the normal 2%,” he added. “The rate of inflation that the market really wants to see in order to get production and distribution and transportation into an efficient allocation has to be more than 2%.”

In addition to helping bring the economy into the new era, DeLong sees another benefit of inflation today: it could help resolve crippling supply chain bottlenecks, resorting to the economic adage that high prices are often the best cure for high prices.

With supply chain issues contributing to high prices and making people less likely to buy, it could be the impetus behind a revitalization and ultimately a strengthening of industry, according to DeLong, who says inflation is involving more people with figuring out either how to produce more of what we need, or less of what we don’t.

“That's the absolutely glorious thing about the market,” he said. “That when prices are aligned with social values, it means that you don't just have one brain or a few brains working on the problem. Everyone's brain is working on the problem. And everybody does what they can to solve it in their immediate circumstance.”

But as always, there’s a catch.

The positive outlook for inflation does come with a caveat, DeLong and other economists admit. Expectations that inflation will become entrenched in the economy and stick around might become a self-fulfilling prophecy, which would lead to something even worse for the economy.

The word for that is stagflation: the worst-case scenario of slow economic growth combined with high inflation. DeLong says it is still very possible.

“Worst of all is you get stuck in the stagflation of the 1970s,” he said. “If inflation gets entrenched in expectations, it will be a very bad thing.”

The ideal situation, DeLong says, would be a repeat of the recessions that hit the U.S. in the late 1940s and early 1950s, both of which were relatively short before inflation subsided.

But a worst-case scenario of stagflation also remains possible, DeLong warned, especially if expectations of inflation become entrenched in the economy.

“Entrenched” has been a bogey word for the Fed this year, and a situation it desperately wants to avoid. Entrenched inflation refers to people expecting prices to keep going up, which can lead to inflation staying around much longer than it would otherwise.

Should inflation become entrenched during a recession, it would be a “very bad thing” for the economy, DeLong said. Whether this will happen will likely depend on the direction gasoline and energy prices take, which have been highly unpredictable so far this year.

“Whether or not expectations get entrenched and we get a 1970s problem really depends on the trajectory of energy prices,” he said. “Inflation expectations are always driven by what people see at the pump.”

Top economists and bankers—including Allianz and Gramercy’s chief economic adviser Mohamed El-Erian and Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon—have warned that inflation is already becoming entrenched and persistent around the world. And the World Bank has issued multiple warnings this year that persistent inflation combined with slow economic growth is leading to a very real risk of stagflation in multiple countries around the world.

Also, not every economist shares DeLong’s view that there is much good at all about the current inflation, with many saying it is a much more pressing issue that the government is failing to adequately control.

Steve Hanke, an economist at Johns Hopkins University, recently criticized the Fed for “incompetence and mismanagement” that has led to inflation, and predicted that the Fed letting the U.S. money supply run short could lead to a “whopper” of a recession next year.

DeLong’s old boss Larry Summers has been singing a dire tune on inflation for over a year, warning last year that the Federal Reserve was being too passive about rising prices. At the release of this week’s CPI report, Summers wrote that the Fed was faced with a “serious inflation problem,” and cautioned that unemployment will likely have to start ticking upward before inflation recedes significantly.

Many economists fear that today’s high levels of inflation, and the Fed’s commitment to containing it, could trigger a recession as early as next year, although the jury is still out on whether this would constitute a deep or shallow downturn.

In a blog post last year, when inflation was already becoming a source of concern, DeLong compared the recovering U.S. economy to a driver suddenly accelerating away. The skid marks left on the asphalt represented inflation—a blemish and a nuisance to be sure—but worth it to get the economy back on track.

A year later, inflation can still just represent a temporary skidmark on the road to recovery, he says. But between the war in Ukraine and uncertain energy markets for the foreseeable future, DeLong admits the outlook is much cloudier now.

“We have energy price inflation and food price inflation springing from Russia and its attack on Ukraine. That is greatly complicating the picture and making the situation much more fraught,” he said.

COMMENT: As I said, my argument here is at its base a strongly right-wing market-fundamentalist argument: people complaining about the inflation that the market has given us need to learn that the market has its logic that we need to respect.

And so I am not surprised but amused that this triggered my first right-wing twitter mob, with 1030 almost-invariably hostile replies:

This is, of course, a very low-wattage right-wing twitter mob in all respects: 1000 angry comments is small beer in these matters, so not much power; there is no there there, in that I have not yet run across a reply in this thread (no, I have not and will not read them all) that gives any evidence of having actually read the Fortune article, so not much attention; and a more-or-less complete forgetting that whining about market outcomes is not a right-wing position in America today, so low IQ.

But it does reinforce my beliefs that Twitter needs to be changed fundamentally. If I were running it, I would give real people one free tweet and ‘bots zero free tweets a day—and make them pay to tweet more. Otherwise, we would be better off without it, and it does need to die.

And I did, at the time, have some comments on Tristan Bove’s story:

The policy discussion surrounding appropriate monetary policy has been greatly hobbled by a lack of attention on the natural rate of inflation—”the level that would be ground out by the Walrasian system of general equilib- rium equations… [accounting for] structural characteristics… including market imperfections, stochastic variability… cost of gathering information… [and] of mobility, and so on…” <https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/58.1.1-17.pdf>. Chief, among these structural characteristics is downward nominal wage stickiness: the extreme inadvisability for worker-morale and hence effort-elicitation reasons of a business attempting to continue to employee a worker at a lower nominal wage.

The first-order implication of this is that the natural rate of inflation will almost always be positive—that, contrary to Milton, Friedman, the long-run Phillips curve is NOT vertical, but, rather that downward nominal wage stickiness requires that the economy have a positive average rate of inflation, in order to grease the wheels of commerce and achieve anything close to an efficient allocation <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2000/01/2000a_bpea_akerlof.pdf>.

The second-order implication of this is that the natural rate of inflation will be higher in times when there is a good deal of reallocation to be done—at times when the economy is not in a stable configuration with respect to sectors and industries, but is instead hunting for a new and different cross-sector and cross-industry relative allocation of effort.

At times like now.

So I ran through the qualitative considerations that impact what the natural rate of inflation is likely to be right now for Tristan Bove of Fortune. And he wrote it up as a very nice little article.

This argument of mine is a very von Hayekian argument: Prices exist to serve as traffic signals so that we can crowdsource the solution to the problem of efficient production. In order to serve as proper traffic, signals, prices need to move to the values that are needed—and we all need to gold and swallow the distributional consequences, or we will empowerish ourselves, relatively, at least. Moreover, one market failure—downward-sticky nominal wages for psychological reasons—does not interfere with the market’s ability to do its job of guiding the crowdsourcing as long as we do not pile on top of that a second market failure: the worship of a stable price level.

One might, indeed, see this as a strongly right-wing market-fundamentalist argument: people complaining about the inflation that the market has given us need to learneth the lesson: “the market giveth; the market taketh away: blessed be the name of the market”, for the market has its logic that we need to respect.

And leet me stress this: given that we have downward-sticky nominal wages in the economy, requiring that the Federal Reserve hit its 2% inflation target year-by-year gravely damages the market economies ability to do its proper job in a time of substantial sectoral activity reallocation.

This is, as I say, obvious. Rapidly returning to a different full-employment configuration after the plague is like rejoining the highway at speed. Inflation is thus like leaving skidmarks—rubber on the road. To complain about leaving skidmarks and also demand that we rejoin the highway at speed is simply silly.

And there is, of course, a big danger: that the interaction of the energy and grain price shocks stemming from Muscovy's invasion of Ukraine with the reopening-shock inflation will cause us to lose inflation’s expectational anchor, and leave us with a big problem. When I point out to Larry Summers that the bond market still thinks that the Federal Reserve has got this, Larry replies: “Yeah. But that is because the bond market expects the Federal Reserve to deliver a big recession to our door.” I think that it is 50%-50% whether that is right—the expectational interest rate path implicit in the term structure does not seem to me to be sending that message. But Larry is not dumb, and his “worry about this issue” positions have greatly risen in their market value over the past twenty-one months.

"And let me stress this: given that we have downward-sticky nominal wages in the economy, requiring that the Federal Reserve hit its 2% inflation target year-by-year gravely damages the market economies ability to do its proper job in a time of substantial sectoral activity reallocation."

That's why the Fed in principle has a FLEXIBLE (forward looking) Average inflation target, my fear is they were too flexible in September 2021 and not flexible enough circa September 2023.

Having complained about newspaper pundits not explaining optimal inflation properly, I should say neither has the Fed. Bad Fed, bad!

And even if it is true that wages, a hugely heterogeneous group of prices (for which we have no proper price indexes; bad BLS, bad!) are the most important place for downward inflexibility, I think for expositional purposes it is less prone to misunderstanding if Fed and pundits stuck to talking about downwardly inflexible "prices" and not spotlight wages. It's likely to spook people like Arthur Burns.

At publication, by my reckoning was just about the time when the Fed should have been starting to pull back. 5- and 10-year TIPS expectations were just going over target

Admittedly the situation is not an easy thing to explain. The "public" still probable think that the optimal rate of inflation is always and everywhere zero and John Cochrane thinks that 2% is just pandering to frailty of central bankers who lack the intestinal fortitude to regard unemployment with a cold Olympian eye (and if it happens during the Administration of a Democrat, so much the better).

Your explanation does get to why why inflation is needed to allow relative prices to adjust to the large, discrete, shock of a change in sectoral demand. It would be better if people understood that this is just the discrete extraordinary version of why some inflation (why not 2%?) is needed to facilitate the gazillion micro shocks of ordinary economic events that require changes in relative prices.

Understanding this however does not mean that more than the minimum amount of inflation to allow relative prices to adjust in not bad. Inflation is bad because

a) There are also prices that are upwardly inflexible,

b) [I assert] trying to make forward-looking decisions which implies guessing future relative prices is more difficult and people are less will do less of it a with worse outcomes,

c) for political economy reasons -- when my wage or price of what I sell goes up I am responding to market demand as a good market participating citizen should; when the price of what I buy goes up it's somebody's fault, the Democrat in the White House or greedy capitalists (but never the Fed) -- and people just HATE it. and even the economists' old favorite,

d) behavior can change to make relative prices less flexible (entrenched expectations).

This means that there is a constantly shifting optimal (balancing costs and benefits) rate of inflation and it's the Fed's job to hit the nail on the head every time the the FOMC meets to set monetary policy instruments (not just ST interest rates) even though the effects of their actions are not immediate. It is an impossible job, but a man's reach should exceed his grasp lest what's there a Heaven for?

Ideally, the public, or at least newspaper pundits would understand what the Fed ought to be reaching for.