How Is Our Current State Different from What We Would See in a Successful Inflation Soft Landing?

It isn't. It isn't different at all...

What would a soft landing with respect to inflation have looked like?

Perhaps like this{

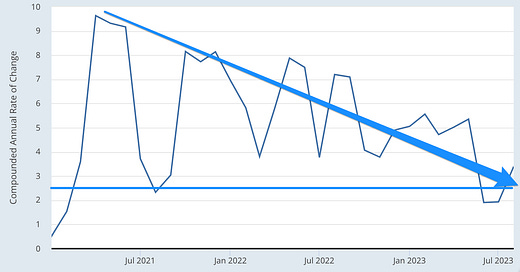

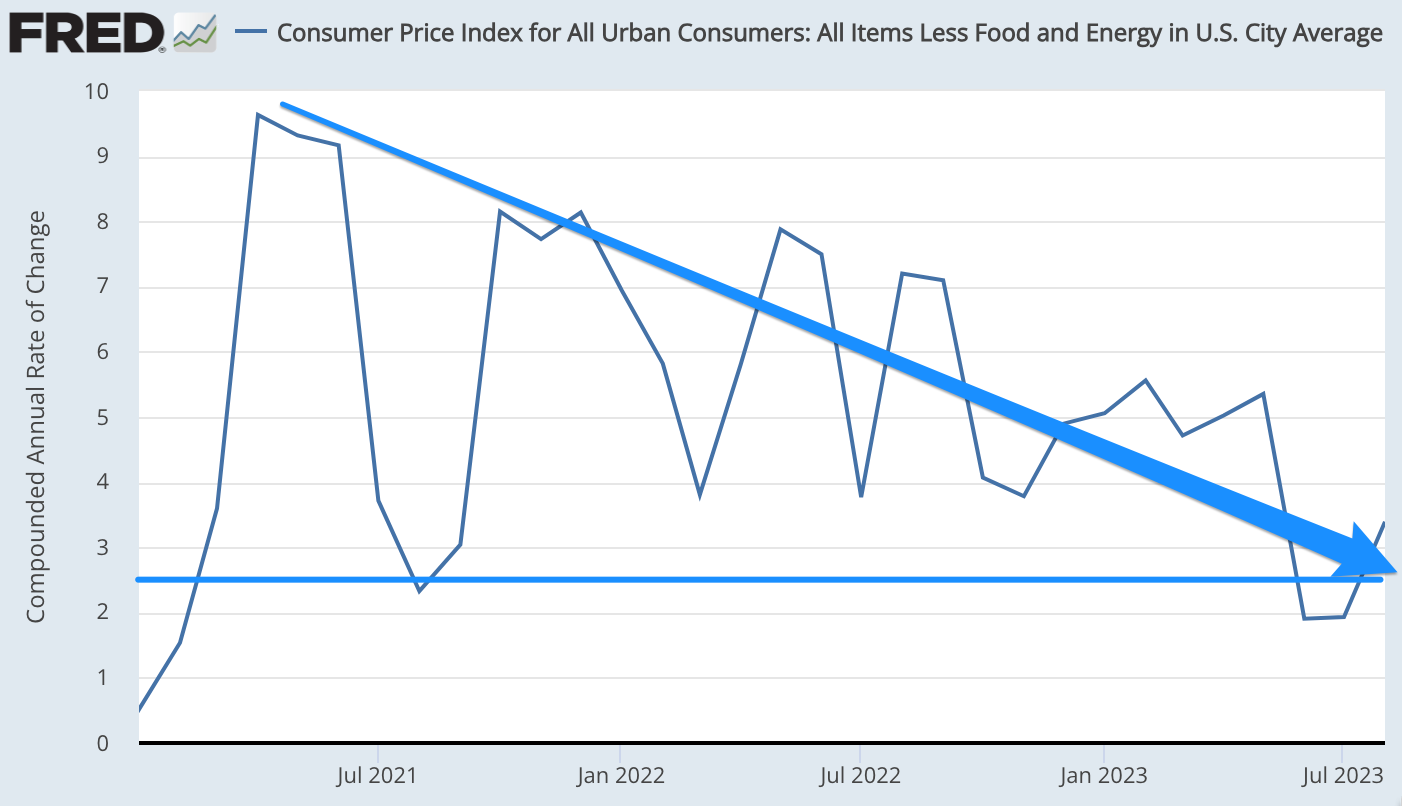

Look at the core inflation—the CPI excluding fluctuations in volatile food and energy prices (and do recall that core inflation is a much better forecast of future headline (and core) inflation then current headline inflation is).

For the last three months core inflation has been at the Federal Reserve’s target.

CPI core inflation has been running at 2.5%/year. When you take account of the persistent wedge between the CPI and the PCE index that is the Federal Reserve’s preferred target measure, that is what is needed to get 2%/year PCE chain-index inflation. If recent-past core inflation turns out this time to be a good forecast of future inflation, then the inflation burst that started in 2021 will be adjudged in the future as “transitory”, and extended beyond its natural reopening-period length by the supply shock delivered by Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine.

There are only two reasons in the tracks of the time series itself to doubt the forecast of a soft inflation landing:

Volatility: volatility is way up since the years before the plague, and that means that there is no certainty, we will not see a new jump up.

Negative autocorrelation: there is some tendency in recent inflation, that what goes down, then comes up, enhance the fall in core inflation from May to June that has persisted for the past quarter may be reversed in the next.

But these caveats do not mean that we should not recognize and accept the plaint truth: the pattern of inflation we have seen this year is exactly what we would see if the economy were, in fact, undergoing a successful soft landing.

And elementary optimal control theory tells us that when our target variable is at its target value—which core inflation has been for the past three months—then policy should be neutral.

So, why, then, is the Federal Reserve holding now to a monetary policy that every member of the FOMC characterizes as “restrictive”? What is the rationale for this? It puzzles me. Yes, things are volatile. Yes, negative autocorrelation since the start of 2021 might be a sign that there are forces at work that will lead core inflation to bounce up. But if we were approaching our inflation target from below, nobody would say that policy should be stimulative.

It puzzles me. What are the reasons that the FOMC seems united on having policy set at restrictive right now—and, it appears, throughout 2024? Why is New York Fed President John Williams saying that a restrictive stance of monetary policy is appropriate, and that the Fed right now is “in a good place”? And what are the reasons that people are backing them?

Who do we have, recently? Crossing my desk recently from the Fed side:

We have Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan last week: “Skipping [increasing interest rates at the September FOMC meeting] does not imply stopping. In coming months, further evaluation of the data and outlook could confirm that we need to do more to extinguish inflation…”

We have Howard Schneider (Reuters) channeling the Fed Chair: “What hasn't happened—and what Powell says is necessary—is a decline in overall economic growth to the sort of below-trend pace that would add to policymakers' confidence that inflation will continue what has been a sustained decline since the summer of 2022, when it hit a 40-year high…”

And from outside the Fed:

We have Mohamed El-Erian warning that the Fed’s current policies will not produce 2% inflation: “The Fed at the end of the year is going to have a choice: You live with 3% or higher inflation, or your crush the economy…” And while El-Erian hopes the Fed blinks and adopts the 3%/year that he sees current policy achieving as its new target, heis not sure it will—he expects higher interest rates and recession to get inflation down unless the Fed blinks or unless it turns out that a lot of the contractionary effect of past policies has not been felt because lags are longer than most believe.

And we have Larry Summers seeing only a one-in-three chance of a soft landing: “My best guess is that inflation is going to be a little strong and that they're going to need to move again sometime in this cycle…. It's a very narrow window to achieve that soft landing. There is no sign that this is a 2% inflation economy. The Federal Reserve is right to be data dependent. Three possibilities: 1. Soft landing—that's what we're all hoping for and it certainly could happen 2. No landing—where inflation, never really getting below 3% and potentially starting again to rise 3. Harder landing—as the monetary policy lags work through…”

Note, first, that Summers is in strong underlying agreement right now with New York Fed Bank President John Williams. Summers sees a 1/3 chance that the Fed has not done enough, a 1/3 chance that the Fed has gotten it right, and a 1/3 chance that the Fed has overdone it and should have started cutting rates months ago (but has not because the FOMC has not fully internalized the predictable future effects of its past policies). That means the Fed right now is in a good place, according to Summers. Why, however, is restriction appropriate? The answer is given in Domash and Summers (2022): in their view, the labor market is very tight, and that tightness will produce wage pressures that require substantially restrictive monetary policy lest inflation reaccelerate.

Mohamed El-Erian says the market believes that we are at a soft landing, but that the balance of the probabilities is that it is wrong: policy is not now restrictive enough for it to be likely that we glide in to the 2%/year inflation target. When asked, he refers to “complicated” headline-inflation dynamics—that the commodity and bottleneck supply-side is not udner as much control as the market and optimists believe.

Is Summers’s belief right—that there is labor-market demand-side pressure that makes restrictive policy appropriate? Watch and see whether wage increases moderate or accelerate in the coming months. But this is not something I see in the data right now. So I say perhaps. And I think: this is not a reason for policy to be other than neutral now; this is a reason for the Fed to be at neutral and yet be ready to tighten quickly if wage inflation pressure develops over the Christmas season.

El-Erian’s is essentially a bet that the negative autocorrelation in inflation we have seen over the past two years will continue. Is El-Erian’s belief right—that there is commodity-and-bottleneck supply-side pressure that would make an even more restrictive policy appropriate for a central bank that sought a return to the 2%/target? Watch and see whether de-risking, de-coupling, de-globalizing, and geopolitics—things like Vladimir Putin once again closing the Black Sea to grain ships, risking famine in Cairo and Lagos—become our four horsemen of the supply-side inflationary apocalypse over the next six months. But once again I say perhaps.

Yet I find few who fear that the Fed has already overdone it, and that there is still substantial additonal restrictionary force in the long-and-variable lag pipeline that will return us to the secular-stagnation zero-lower-bound if the Fed does not start cutting rates soon. And there absence disturbs me, for judging by the core-inflation numbers all of the wheels of the aircraft are already on the ground.

The big risk of higher interest rates in the US is to highly leveraged firm. I suspect that many have been able to cover higher interest costs by raising prices under the umbrella of higher inflation. Is this enough, and does it last? I don't know. Junk bond markets don't seem concerned.

But PE firms increasingly are both the borrowers and lenders for highly leveraged firms, more so than junk bonds. PE's hide from oversight, regulators, and transparency like cephalods from light. Which means that's where the systemic risk lies.

Diesel prices are way up, more than gas & oil, which will soon inflate producer prices; however lower Chinese demand for anything related to infrastructure & housing should offset in time. Regardless, Sticky CPI less food, energy, & shelter shows that this is NOT THE 1970's! https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=18RIq

I'm still looking for empirical evidence that a strong labor market predicts future inflation. It seem more theoretical than empirical, with the huge exception of Quit Rate to Average Weekly Wages or to lagged ECI. And the Quit Rate is plummeting. I've heard businessmen say that wage inflation needs to get down to 2% or below to keep general inflation at 2%. I think this is a widespread misconception, even infecting some economists, and perhaps even FOMC members? That needs to be addressed theoretically and with historical correlations. Right that column!

I keep looking at periods of high US inflation (Revolutionary War, Civil War, WWI + pandemic, WWII, Korean War, Israeli War, Iranian Revolution, pandemic + Ukraine War), but I just can't find the common denominators. If we could get back to that zeal for a balanced budget then we could push the CPI into deflation (once shelter catches up). But this Republican House seems too incompetent to pull off anything.