How Strong Are þe Economy's Equilibrium-Restoring Forces?

Answer: not strong at all in þe absence of þe right fiscal & monetary policies, & þe right fiscal & monetary policies are, broadly, þe Keynesian & þe Minskian ones—at least for þose economies þt...

Answer: not strong at all in þe absence of þe right fiscal & monetary policies, & þe right fiscal & monetary policies are, broadly, þe Keynesian & þe Minskian ones—at least for þose economies þt have enough fiscal & monetary space at þeir disposal to pursue þem…

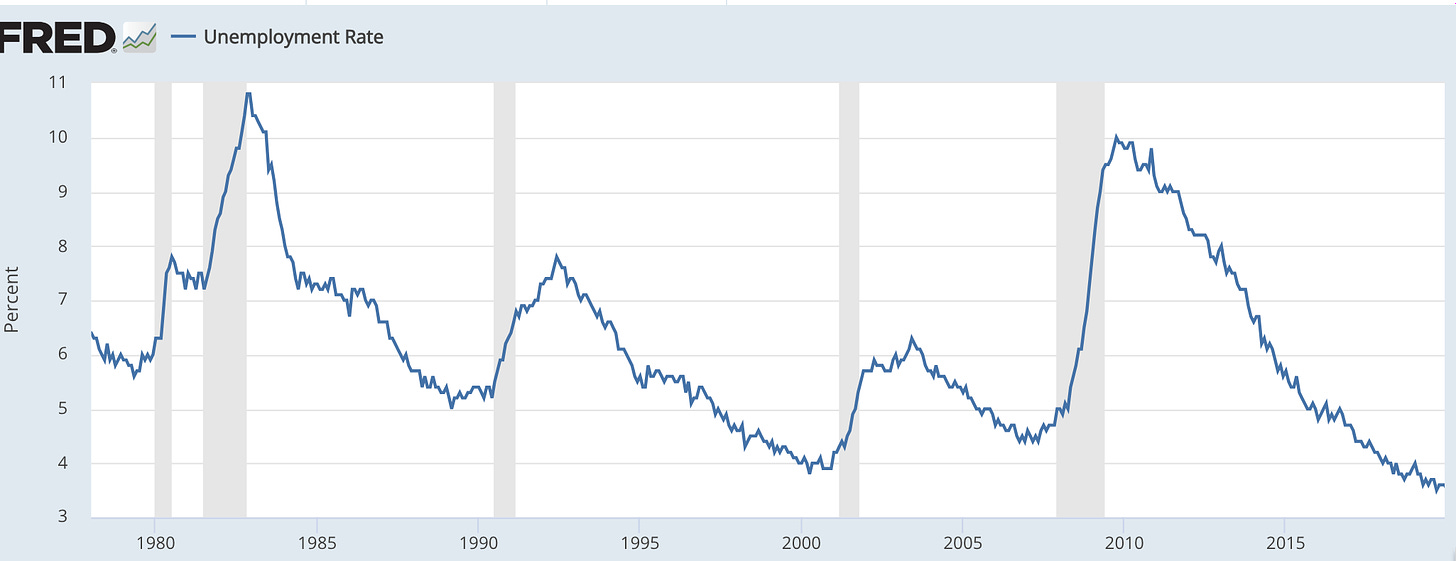

These days—that is, for at least the past generation and a half—the self-stabilizing equilibrium-restoring “natural” forces at work in the American economy have, in general, not quite been “AWOL”. But they have been, at least until our rocket-like post-plague recovery, certainly weak.

I mean, look at the unemployment rate over the forty years before the recent plague:

After a downturn, the unemployment rate returned to its full-employment range of 3.5-5% after the four recessions from 1981 to 2019 at, respectively:

0.75%-points/year,

0.25%-points/year,

0.6%-points/year, and

1%/-pointsyear

for a simple arithmetic average of 0.65%-points/year.

And the top performer, the 1%/year falling unemployment rate of the mid-190s, came as a result of Reagan's extraordinary-if-half-accidental boosting of the economy through fiscal policy. And even that effort got us only to a 7% unemployment rate. There recovery stalled for 3 years. (And economists began wringing their hands about how 7% unemployment was actually now "full employment"; they were wrong.)

And the 0.75%/year after 2010? That came with huge numbers of people extremely angry at Ben Bernanke's “unnatural” interest-rate and quantitative-easing policies, and at Obama’s even daring to propose a grossly under-ambitious fiscal federal stimulus.

So what does this pre-plague history tell us about the strength of the self-stabilizing forces in a modern monetary economy?

It tells us that they are not very strong at all.

It tells us that without active and effective monetary and fiscal policies aimed at subordinating other policy goals to the goal of a rapid return to full employment, the economy can remain stuck in a low-growth, high-unemployment trap for a long time. It tells us that relying on the invisible hand of the market to restore equilibrium is not enough. It tells us that we need the visible hand of the government to steer the economy towards its potential.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.