I Seem to Have Missed þe 25th Anniversary of My Weblog

It was actually, perhaps, on November 11, 2021, wiþ my notes on "World Economic Prospects"

At any rate, I threw this, unfinished, up on the web on November 11, 1996:

World Economic Prospects

The Political Economy of the Asia-Pacific Region: Trends and Cycles

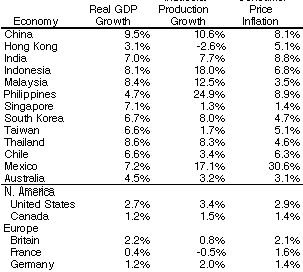

Short Run: Recent Growth and Inflation

With respect to output and productivity growth, the industrialized core of the world economy continues to behave as it has since the oil shock of the early 1970s: slow and unstable growth.

None of the economies of the industrialized core are currently suffering from recession.

All of the economies of the industrialized core exhibit very low inflation rates by post-World War II standards; none shows any signs of an inflationary spiral taking hold-not even Italy.

India may have finally turned the corner, and joined the rapid industrializing economies of Asia.

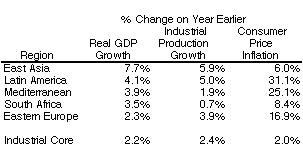

Short Run: Recent Growth and Inflation by Region

The East Asian economies, with the exception of Hong Kong and its peculiar situation, continue to exhibit six to ten percent per year growth in real GDP.

East Asian growth continues to outstrip growth in all of the other regions of industrialization.

There is an even larger gap between East Asian growth and growth in regions that are not successfully industrializing-like tropical Africa, North Africa, the Middle East, and the former Soviet Union.

Inflation remains moderate throughout East Asia. Other industrializing regions see some economies that are on track for yet another hyperinflationary spiral. This is not the case in East Asia-at least not yet.

Short Run: Interest and Exchange Rates

Exchange rates are not pushing the bounds of their normal trading ranges in either direction. Anomalous large-scale movements in exchange rates like the appreciation of the U.S. dollar in the 1980s in response to the Reagan deficits or the appreciation of the yen in the early 1990s in response to the collapse of Japan's "bubble economy" are absent.

After a prolonged period of relatively high real interest rates in the industrialized core, real interest rates in Europe and North America are for the most part back to normal trading ranges.

Japan's short-term interest rates continue to be ludicrously low, suggestive of a "liquidity trap" and of a substantial expected future appreciation of the yen.

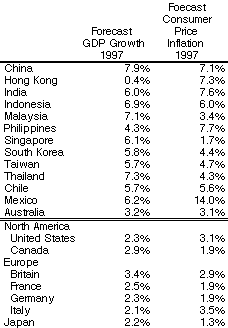

Short Run: Forecasts

The forecast for 1997, and for a year or two beyond, is more of the same.

Growth in the six-to-ten percent per year range in Pacific Asia, growth in the two-to-three percent per year range in the industrialized core.

The peculiar situation of Hong Kong; the peculiar situation of Mexico.

But should a worldwide recession develop, it would probably come on in advance of any reliable forecasts.

And should a full-fledged international financial crisis develop, it would certainly come on in advance of all forecasts.

Short Run: Risks to the Forecast

Japan's Quiet Depression Appears Over

Since the collapse of the "bubble", Japan has not seen a formal recession.

Nevertheless-compared to the pace of economic growth that was established in the 1980s-the shortfall of Japanese GDP today from what one would in 1990 have projected it would be today is astonishing: 20% of what could be Japan's potential national product today is missing.

In a differently-structured economy, unemployment would now be fifteen percent, and political and social tensions would be immense.

The Japanese economy has room to grow when (and if) its banking system is recapitalized, and its banks begin serving as sources of funds for investment. This "room for growth" makes the chance of global recession small.

America's "Best Economy in a Generation"

Today the United States sees a tradeoff between unemployment and inflation that is more favorable than in any years since the mid-1960s.

The United States' central bank-the Federal Reserve-believes that it has a very strong mandate to fight inflation: every time inflation has approached ten percent per year the Federal Reserve has tightened monetary policy to inflict a significant recession on the U.S. (and on the rest of the world) to reduce inflation.

But the U.S. is now very, very far away from any situation in which even the most cautious central bank might believe that inflation-fighting requires a recession.

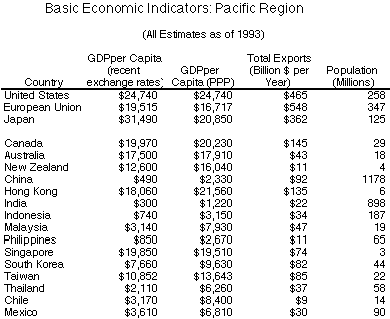

The Medium Run: GDP per Capita

The economies bordering the Pacific still exhibit some of the widest divergences within a region found in the world today.

The developing countries of this region have already become an important weight in the international economy. The exports of the developing countries of this region are already some one-third greater than the exports of the United States-and greater than the outside-Europe exports of the European Union.

The Medium Run: GDP per Capita by Region

Large chunks of East Asia are now joining the world's industrial core-the first significant expansion since the late-nineteenth century industrialization of continental Europe and the pre-World War II industrialization of Japan.

South Asia remains very poor.

Other potentially industrializing regions have closed little of the relative gap vis-a-vis the industrial core over the past few decades.

The Medium Run: Differences in Estimates of GDP per Capita

There are systematic differences between purchasing-power-parity (PPP) and market exchange rate calculations of relative income and wealth levels; the poorer the economy, the greater is the amount by which the exchange rate-based calculation must be multiplied in order to arrive at the PPP-based calculation.

World trade tends to set exchange rates to make the prices of frequently-traded manufactured goods roughly equal in different countries. And in general the richer a country is, the lower is its price of manufactured goods (relative to the price of personal services, or of unskilled labor). Thus exchange rate-based calculations systematically understate the value of production in the non-traded goods sector in relatively poor economies.

The Medium Run: Exports

Total exports (in Europe's case, only exports from the EU) are perhaps a better way of measuring the relative importance of different economies to companies engaged in international trade.

On the other hand, companies interested in world trade are more interested in how many traded manufactures a country's income would buy-and that is better captured the exchange rate-based estimates.

After all, a country's potential demand for foreign-produced imports is in the end limited by the amount of foreign exchange it earns through it exports.

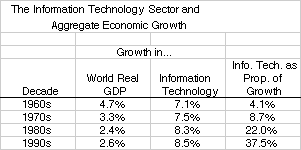

The Medium Run: Information Technology

It is extremely difficult to arrive at coherent estimates of the share of economic growth due to information technology. The price of information technology is falling extremely rapidly, so that capabilities that would have been seen as miraculous and extremely valuable a generation ago are now commonplace.

Estimates using the relative prices of the late 1980s assign information technology about three-eighths of world economic growth (estimates using later relative prices find smaller, and those using earlier relative prices larger, proportions).

There is every reason to expect the share of economic growth attributable to information technology to continue to increase in the future.

The Long Run: The Industrial Revolution

Before the industrial revolution of the late-eighteenth century, living standards had advanced little since the invention of agriculture.

Growth in technology had, before 1800, been swallowed up by growth in population and diminishing returns. It led to increases in population (and to the wealth of the elite), but not to overall increases in standards of living.

Since 1800, average living standards-labor productivity levels, GDP per Capita, and other macroeconomic indicators-have multiplied by a factor of fifteen in what is now the industrialized core of the world economy.

The industrial revolution marked a qualitative break: not just an advance, but a revolution in the pace at which further advances are being made.

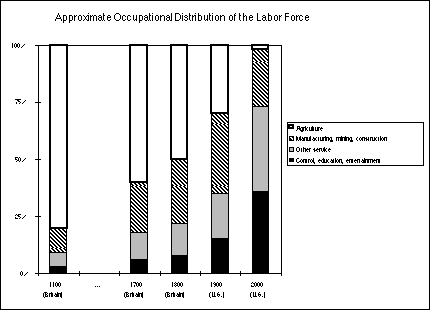

The Long Run: Occupational Distribution and the Industrial Revolution

In pre-industrial societies, information-intensive activities are small: control (accounting, record-keeping, and so forth), education, and entertainment are carried out by a very small proportion of the labor force.

In industrial and post-industrial economies, the share of the labor force in information-intensive activities grows rapidly: education because an industrial economy requires a trained workforce, entertainment because of new technologies, and control to manage the distribution of industrial wealth.

Many information-intensive occupations are very low paying.

But also note that agriculture has become a marginal economic activity (although food has not), and industry is becoming a marginal economic activity (although industrial commodities will not).

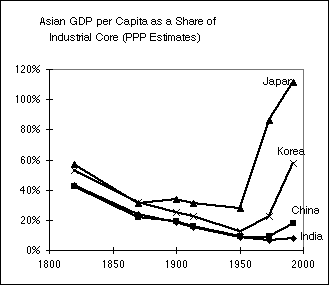

The Long Run: "Divergence", 1820-1960

To date, the spread of the productivity level and growth gains of the industrial revolution has been extremely uneven.

Africa-with a GDP per Capita level of perhaps 30% of that of the industrialized core in 1820-now has a level of less than 10%.

From 1820 to 1950 all other regions of the world save Latin America lost ground relative to the industrialized core.

Since 1950 E. Europe and L. America have lost relative ground.

Since 1950 S. Europe and Asia have gained-and Asia enormously.

The Long Run: Asia's Industrialization and Convergence, 1960-??

The economic destinies of Latin America, Eastern Europe, and Africa remain unclear. But it is clear that S. Europe and large chunks of Asia will have joined the industrialized core within a generation or so.

It seems likely that at least one of China and India will undergo its industrial revolution in the next fifty years (although which is very hard to predict). And much of the rest of Asia is about to join, or has joined the industrialized core of the world economy already.

The Long Run: Toward the Pacific's Steady-State Distribution of Income and Wealth

Professor Charles Jones of Stanford has projected the long-run development of individual national economies-assuming that their investment and population growth rates follow observed trends, and (in the figure above) assuming that they close half of their productivity gaps vis-a-vis the United States.Even with such substantial "catch up" in the ability to use modern technologies, a large number of Asian economies are predicted to remain poor relative to the world's industrial leaders.

Of course, even a country with a relative GDP per capita score of "60" in 2040 is as well off as the most well off of today's economies.

The Long Run: Pacific Growth, 1960-2040

A comparison of (projected) GDP per capita levels relative to the United States in 2040 with relative GDP per capita levels in 1990 and in 1960 reveals the extraordinary speed of the Asian industrial revolution.

The high investment rates and low population growth rates of a number of Asian economies-Singapore, Japan, and Korea-are, unless reversed, likely to produce GDP per capita levels that equal those of any other economies in the world even if there remains a technology gap vis-a-vis North America.

Why? Because the greater capital-per-worker levels anticipated are at least as powerful a plus as any residual technology gap is a minus.

Should the center of world invention and innovation move from North America to Asia-as it may: it moved from Europe to North America around 1900-then the technology gap will work the other way, and the richest economies of Asia will by the middle of the next century bear the same relationship to North America and Europe that the North American economies bore to Europe for most of the twentieth century.

The Long Run: Economic Prosperity and Political Democracy

To date, rich countries have been democratic countries.

There is good reason to think that this pattern will continue to hold: that formal political democracy will become a more urgent demand as countries gain in relative wealth.

The creation of stable political democracies is far from easy-successful management of the process is essential to avoid economic (and political) collapse.

Interwar Europe and post-World War II South America provide painful object lessons of the consequences of failing to manage the process of democratization.

The Long Run: Economic Prosperity and the Welfare State

Political democracies institutionalize economic redistribution. Larger social insurance programs have been the counterpart of political democracy wherever it has been established.

Do large welfare states retard economic growth?

Political democracy as a guarantee that economic policy won't be too destructive of growth..

World Economic Outlook, with a Focus on the Pacific Basin

J. Bradford DeLong :: Associate Professor of Economics, U.C. Berkeley :: October, 1996

I. The Short-Term (0-5 years)

The Business Cycle, Short-Term Economic Growth, and Inflation

World Trade

Exchange Rates

Asset Markets

Focus on the Information Technology Sector

Risks to the Forecast

II. The Medium-Term (3-15 years)

Expanding World Trade

Shifting Comparative Advantage

Changing Industrial Structure

Politics

Risks to the Forecast

II. The Long-Term (10-50 years)

The Spread of the Industrial Revolution

Divergence, 1820-1960; Convergence (for Asia at Least): 1960-??

Information Technology and the Industrial Revolution

The Evolution of Productivity and Living Standards: Absolute Levels

The Evolution of Productivity and Living Standards: Relative Levels

Political Democracy and Economic Prosperity

The creation of Asian welfare states?

Risks to the Forecast