Immigration & the American Psyche :: American Economic History

mmigration has always been at the heart of America’s story & self-definition. It has also one of the if not the major source of America’s power & prosperity. But anxiety about welcoming immigrants...

Immigration has always been at the heart of America’s story & self-definition. It has also one of the if not the major source of America’s power & prosperity. But anxiety about welcoming immigrants has also always been a constant. Romulus established an asylum when he founded ancient Rome—a place welcoming fugitives, exiles, criminals, runaway slaves, and other marginalized or displaced individuals from elsewhere & making them full Roman citizens. Pre-Severan Dynasty Rome thus joined America as the only other ethnicity that self-defined not as descendants of a (usually fictional) small group of ancestors bound by blood and to the soil, but rather as something you could join as long as you pledged yourself to its cultural-political project. Welcoming outsiders has driven economic growth, cultural exchange, and political upheaval here in America. Will today’s debates about immigration end in a sharp break from tradition—and a likely draining-away of American prosperity and power. Or will they end in a return to the centuries-old pattern?

First part of this year’s “Immigration” Lectures: To be followed by: “Immigration & the American Century”

Immigration in the United States: Patterns, Policies, and Impact

Immigration played a crucial role in shaping what the United States came to be.

Since the early 1600s century, waves of immigrants have arrived in the land that is now the United States of America. The population flow has been driven by economic opportunity, declining transportation costs, and established networks of previous migrants.

The history of immigration has been dominated by the nation's openness to newcomers. But that openness has fueled periodic backlashes driven by social and political anxieties.

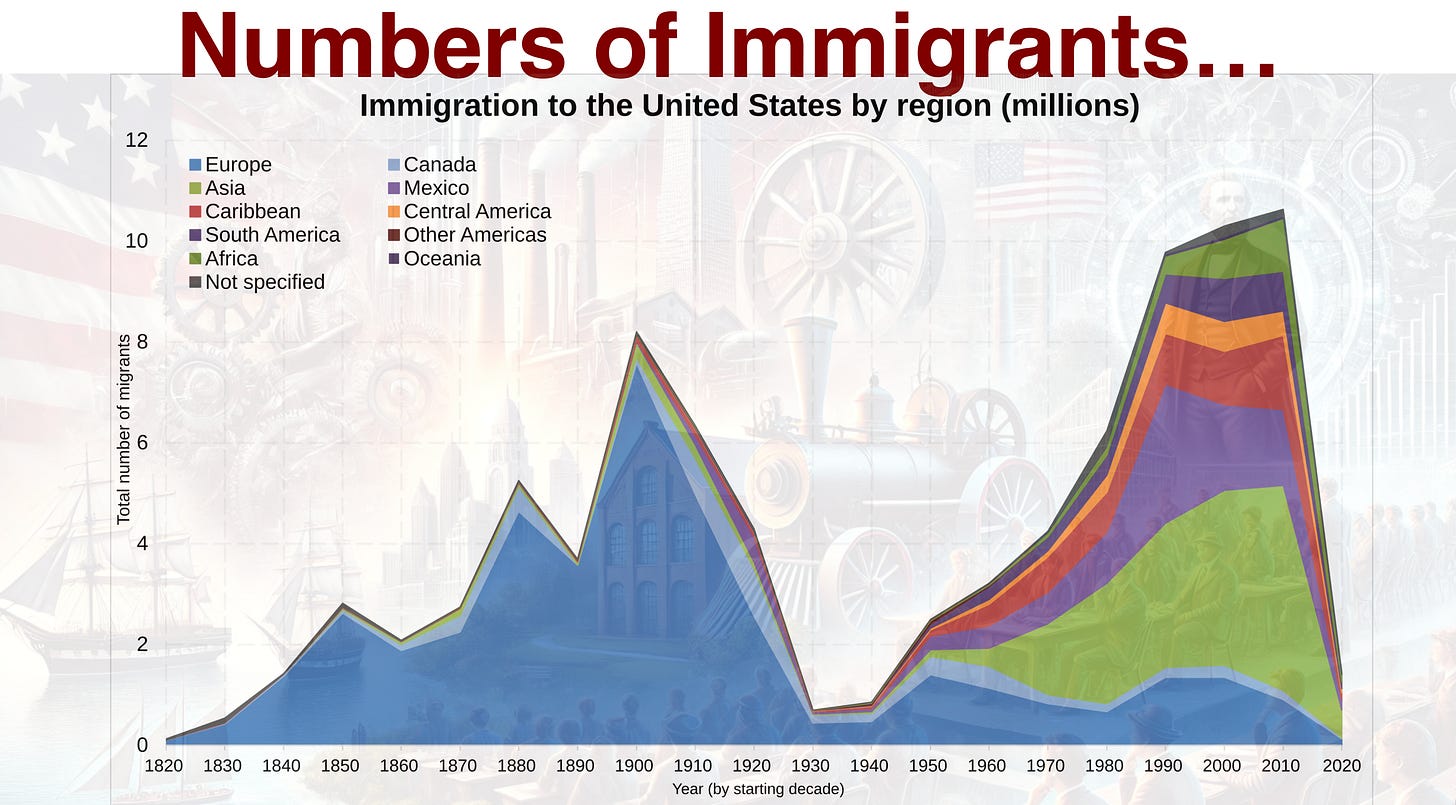

Immigration Trends from 1820 Onward

From the first European settlement through the early 20th century, immigration to the United States rose steadily. European immigrants dominated these waves, with England and Scotland coming first, Germany second, Ireland third, and other immigrants mostly from northern and western Europe coming alongside in smaller numbers. The pace of immigration fell off during the Civil War and the economic depressions of the 1890s. But the overall trend was clear, and ever upward. Transportation costs fell, the expanding settlement-conquest resource-grab society preserved America’s high wage differential vis-à-vis Europe, information about life in America spread, and migration networks expanded. Increasingly, communities across Europe had ties to family members or neighbors who had successfully established themselves in the United States, and would offer to give relatives or the friends of relatives a helping hand up.

Mass immigration from China was cut off in the 1880s. And the overall steady flow of immigration from Europe was severely disrupted after World War I. The 1920s in America saw a sharp majority political and cultural reaction against immigration, rooted in fears that newcomers were undermining American society. This culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924, which drastically restricted immigration by implementing national origin quotas, restricting immigrants from a country to a proportion of those immigrants who had already come. These quotas favored immigrants from Northern and Western Europe: their annual quotas were never filled. These quotas greatly limited arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as elsewhere.

As a result, immigration rates plummeted throughout the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. It wasn’t until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that these restrictions began to be gradually lifted, ushering in a new wave of migration.

By the late 20th century, immigration numbers (but not proportions) had risen to historic highs, with migrants arriving not only from Europe but also and more so from Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

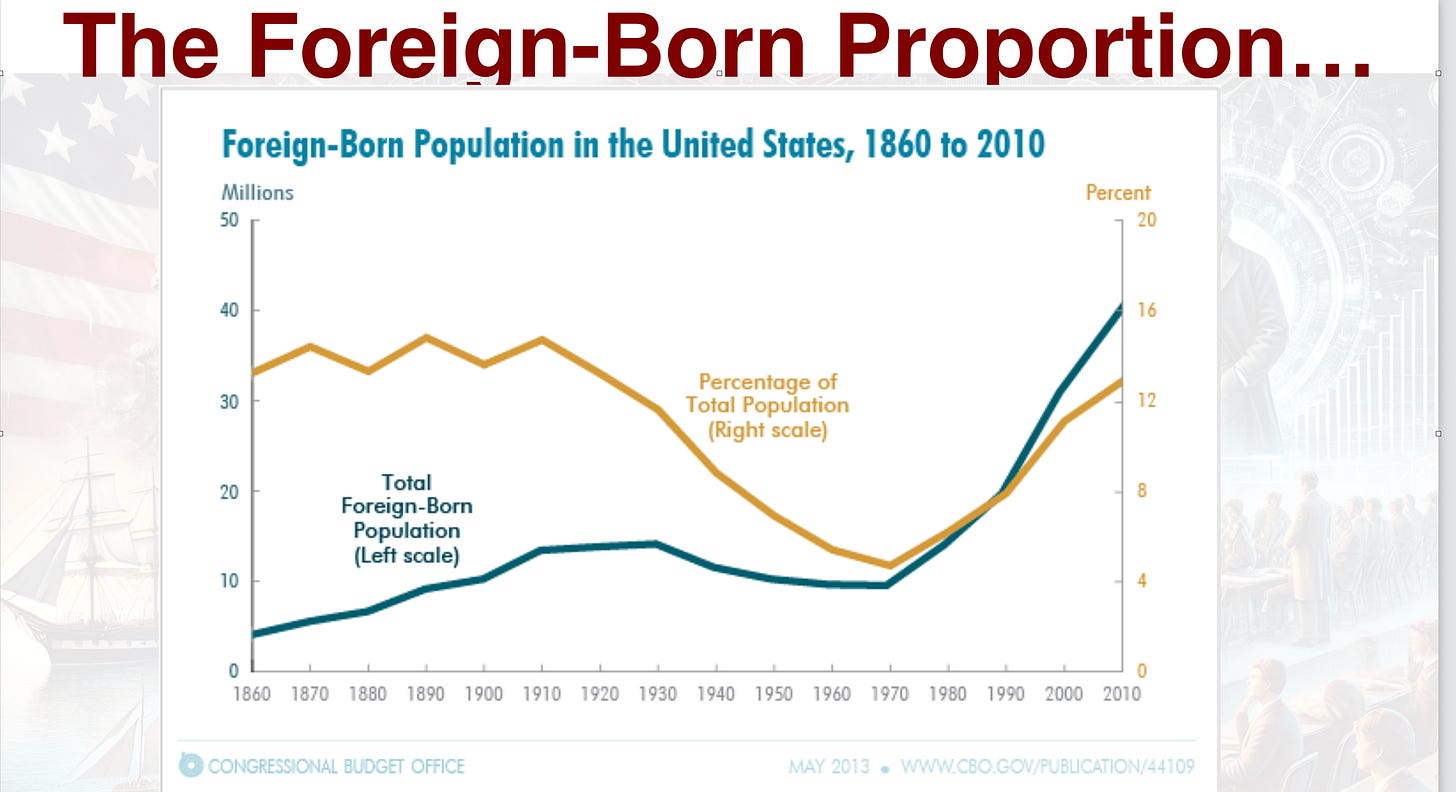

The Changing Proportion of Foreign-Born Americans

The proportion of the U.S. population that was foreign-born has fluctuated significantly over time. In the colonial period, the majority of all non-First Nations people were immigrants. As of 1800, immigrants made up more than 25% of the population. This percentage gradually declined to around 14% by the time of the Civil War, and their it stuck steady through the early 1900s until 1930.

Following the restrictive immigration policies of the 1920s, the share of immigrants in the population began to fall, reaching a low of about 5% by 1970. Since then, the proportion has risen steadily, returning to pre-1930 levels. Much of the anxiety about immigration in recent decades reflects a return to what was, historicallym normal for the United States—a diverse, immigrant-rich society, with the foreign-born amounting to one in seven residents, and with perhaps one in four being visibly culturally alien to the dominant WASP-based American culture by reason of their birth or their immediate descent from those born elsewhere.

Cultural & Political Impact: Panic

And so immigratiion has long sparked political debate in America. Historically, curiously—or perhaps not—concerns about newcomers have often been strongest in regions with the fewest immigrants, both absolutely and relatively.

Rural areas and smaller towns, where immigrants were scarce, tended to express greater anxiety about cultural change than major cities, which have always been immigrant hubs.

This tension has deep historical roots. Periodic fears that immigration is "polluting" American identity have existed since the early 20th century and have resurfaced in recent decades.

The question remains: Did the relatively low immigration levels from 1940 to 1980 fundamentally alter American self-perception? Has the United States shifted from a country that celebrates its immigrant roots to one that sees itself as a more closed, "blood-and-soil" nation? Or is America’s psyche today back to what it was for most of its history, as a place that gloried in its acceptance of immigrants, with nay-sayers confined to a minority.

But the nay-sayers have long been a powerful minority.

We have, writing in 1891, Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, and his “Lynch Law & Unrestricted Immigration” <https://www.jstor.org/stable/25102181>, expressing deep concerns about immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe. Unrestricted immigrationm, in his view, posed a significant threat to American society by introducing dangerous criminal organizations like the Mafia, the Molly Maguires, and the Secret Polish Avengers. Lodge believed that secret societies rooted in immigrant communities posed a unique danger to public order, as these groups not only facilitated criminal activity but also undermined social cohesion. He cited the lynching of 11 Italian immigrants in New Orleans as a grim example of societal backlash against such threats.

One of Lodge’s key accusations was that so-called "benevolent societies" elsewhere actively encouraged undesirable migrants—including criminals, ex-convicts, and impoverished individuals—echoes of “they’re eating the dogs! they’re eating the cats!… they’re emptying the asylums”—to leave their home countries and settle in the United States, and so sought to reduce their own nation's lumpenproletariat and the accordant social burdens by shifting them to America.

Plus Lodge—falsely—thought the new immigrants speaking languages outside the German branch of the Indo-Europen language tree as reluctant to assimilate. He claimed that these groups resisted adopting American social and political norms, instead reinforcing ethnic enclaves that hampered national unity. Lodge’s concerns extended beyond crime and social integration; he also linked immigration to radical political ideologies: socialism and anarchism.

Of course, an anti-immigrant senator from Massachusetts in any generation previous to Lodge would have denounced not just the Molly Maguires but all of the immigrants from Ireland. But in Henry Cabot Lodge’s day every politician in Massachusetts at least lumped the Irish—even Catholic Irish—into a single good-immigrant category, as people from the “British Isles”.

Lodge was far from alone in his socio-cultural panic. We find an even stronger such argument from future President Woodrow Wilson. The end of Wilson’s 1893 history textbook, Division and Reunion, 1829-1889 <https://archive.org/details/divisionreunion100wilsuoft>, identifies three threats to America: Mormons, spendthrift Republicans, and immigrants: New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. .

The other leading questions… the granting of pensions and the regulation of immigration. Congress had hastened from one lavish vote to another in providing pensions for the soldiers who had fought in the civil war, until at length generosity had passed into folly. President Cleveland for the time put a stop to the reckless process by a vigorous use of his veto power.

Immigration had long since become a threat instead of a source of increased wealth and material strength, bringing, as it did, the pauperized and the discontented and disheartened of all lands, instead of the hopeful and the sturdy classes of former days; and public opinion was becoming veryn restless about it. But Congress did little except act very harshly towards the immigrants from a single nation. By an Act of 1888 the entrance of Chinese into the country was absolutely cut off.

Congress undertook… to deal in summary fashion with polygamy among the Mormons of Utah. The charter of the Mormon church was declared forfeit, polygamy was made criminal, and all persons were excluded from the elective franchise in the Territory who would not take oath to obey the stringent provisions of the federal statutes… aimed at the principal domestic institution of the Mormon sect…

Before his hopeful conclusion:

The end of the first century of the Constitution had come… but twenty-four years since the close of the war between the States; but these twenty-four years of steam and electricity had done more than any previous century could have done to transform the nation into a new Union. The South… freed from the incubus of slavery, she had sprung into a new life… lost her old leisure and her old-time culture, but began very fast to build… material foundations…. The old alienation of feeling between the sections could not survive…. Days of inevitable strife and permanent difference came to seem strangely remote….

New troubles came, hot conflicts between capital and labor; but the new troubles bred new thinkers…. New problems quickened sober thought, disposed the nation to careful debate of its future. The century closed with a sense of preparation, a new seriousness, and a new hope…

And more than a century before Lodge and Wilson we had Benjamin Franklin, still then a loyalist focused on the transatlantic British identity, and not at his best:

A Nation well regulated… [if you] cut it in two… each deficient Part shall speedily grow out of the Part remaining. Thus [with]… Room and Subsistence… you may of one make ten Nations, equally populous and powerful; or rather, increase a Nation ten fold in Numbers and Strength…. Detachments of English [sent] from Britain… to America, will have their Places at Home so soon supply’d and increase so largely here.

[So] why should the Palatine [German] Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements, and by herding together establish their Language and Manners to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania… become a Colony of Aliens, who… Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion….

The Number of purely white People in the World is proportionably very small. All Africa is black or tawny. Asia chiefly tawny. America (exclusive of the new Comers) wholly so. And in Europe, the Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes, are generally of what we call a swarthy Complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only excepted, who with the English, make the principal Body of White People on the Face of the Earth.

I could wish… [White People’s] Numbers were increased…. While we are… clearing America of Woods, and so making this Side of our Globe reflect a brighter Light to the Eyes of Inhabitants in Mars or Venus, why should we in the Sight of Superior Beings, darken its People? Why increase the Sons of Africa, by Planting them in America, where we have so fair an Opportunity, by excluding all Blacks and Tawneys, of increasing the lovely White and Red?…

The only saving grace is Franklin’s “and Red”. For Franklin, America is for the Amerindians as well as for the British (and Saxon!) ethnicity.

Cultural & Political Impact: The Majority Pro-Immigrant American Self-Definition

But these nay-sayers were a definite minority. Not until 1924 did anything significant restricting truly open borders other than the Chinese Exclusion Act become law.

The majority has always been best expressed by the strongly pro-immigrant J. Hector St. John Crèvecœur and his 1782 Letters from an American Farmer <https://dn720206.ca.archive.org/0/items/bim_eighteenth-century_letters-from-an-american_st-john-de-crvecoeur-_1782_0/bim_eighteenth-century_letters-from-an-american_st-john-de-crvecoeur-_1782_0.pdf>:

What then is the American; this new man?… That strange mixture of blood, which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you a family whoſe grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch, whose son married a French woman, and whose preſent four sons have now four wives of different nations.

He is an American; who leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, recieves new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys, and the new rank he holds. He becomes an American being received in the broad lap of our great Alma Mater. Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity will one day cause great changes in the world. Americans are the western pilgrims, who are carrying along with them that great mass of arts, sciences, vigour, and industry which began long since in the east; they will finsſh the great circle. The Americans were once scattered. all over Europe; here they are incorporated into one of the finest systems of population which has ever appeared, and which will hereafter become diftinct by the power of the different climates they inhabit.

The American ought therefore to love this country much better than that wherein either he or his forefathers were born. Here the rewards of his industry follow with equal steps the progress of his labour; his labour is founded on the basis of mature self-interest; can it want a stronger allurement? Wives and children, who before in vain demanded of him a morsel of bread, now, fat and frolicksome, gladly help their father to clear those fields whence exuberant crops are to arise to feed and to clothe them all; without any part being claimed, either by a despotic prince, a rich abbot, or a mighty lord. Here religion demands but little of him; a small voluntary salary to the minister, and gratitude to God; can he reſuse these?

The American is a new man, who acts upon new principles; he must therefore entertain new ideas, and form new opinions. From involuntary idleness, servile dependance, penury, and useless labour, he has passed to toils of a very different nature, rewarded by ample subsistence;—This is an American…

Coming to the New World to build a society free from the grievous mistakes of the Old World, and showing the unlucky elsewhere what a truly good—a truly utopian—society could be. And all welcome just as long as they arrive and pledge themselves to the project of America.

In world history, it is unique. Or, rather, almost unique. Something similar took place in Rome. The founding myth was that when Romulus founded the city, one of the first things he did was establish the Asylum between the Arx, the citadel peak of the Capitoline Hill, and the other peak on which was built the Templus Iovis Optimus Maximus. Make it to the Asylum and pledge yourself to Rome, and you were a Roman citizen. No matter what you had been, people—whether fugitives, exiles, criminals, runaway slaves, or otherwise marginalized or displaced—were Romans, hardy and ambitious even though lacking in social refinement. Like being an American, being a Roman was an ethnicity you could decide to join. That lasted up until the year 200 or so, when the Roman citizen body began to be divided into honestores and humiliores.

In the Roman case, making Roman ethnicity a matter of election and adoption (provided you found a patron willing to sponsor you) shook western Eurasia and North Africa for more than a millennium. In the American case, making American ethnicity a matter of election and adoption has shaken the world for two centuries. But will it last? And for how much longer?

Economic and Demographic Consequences

Immigrants have been essential in building the modern United States. Without sustained immigration, America's population today would likely resemble that of Canada or Australia—perhaps only 60 million people rather than the 330 million we see today.

The idea that immigration drives growth is supported by the simple math of population expansion. Even with natural increases in birth rates, the absence of immigration would have severely limited America's workforce and economic potential. Immigrants have filled critical roles in industry, agriculture, and services, contributing to the country’s prosperity.

But Is America Today Out of Room?

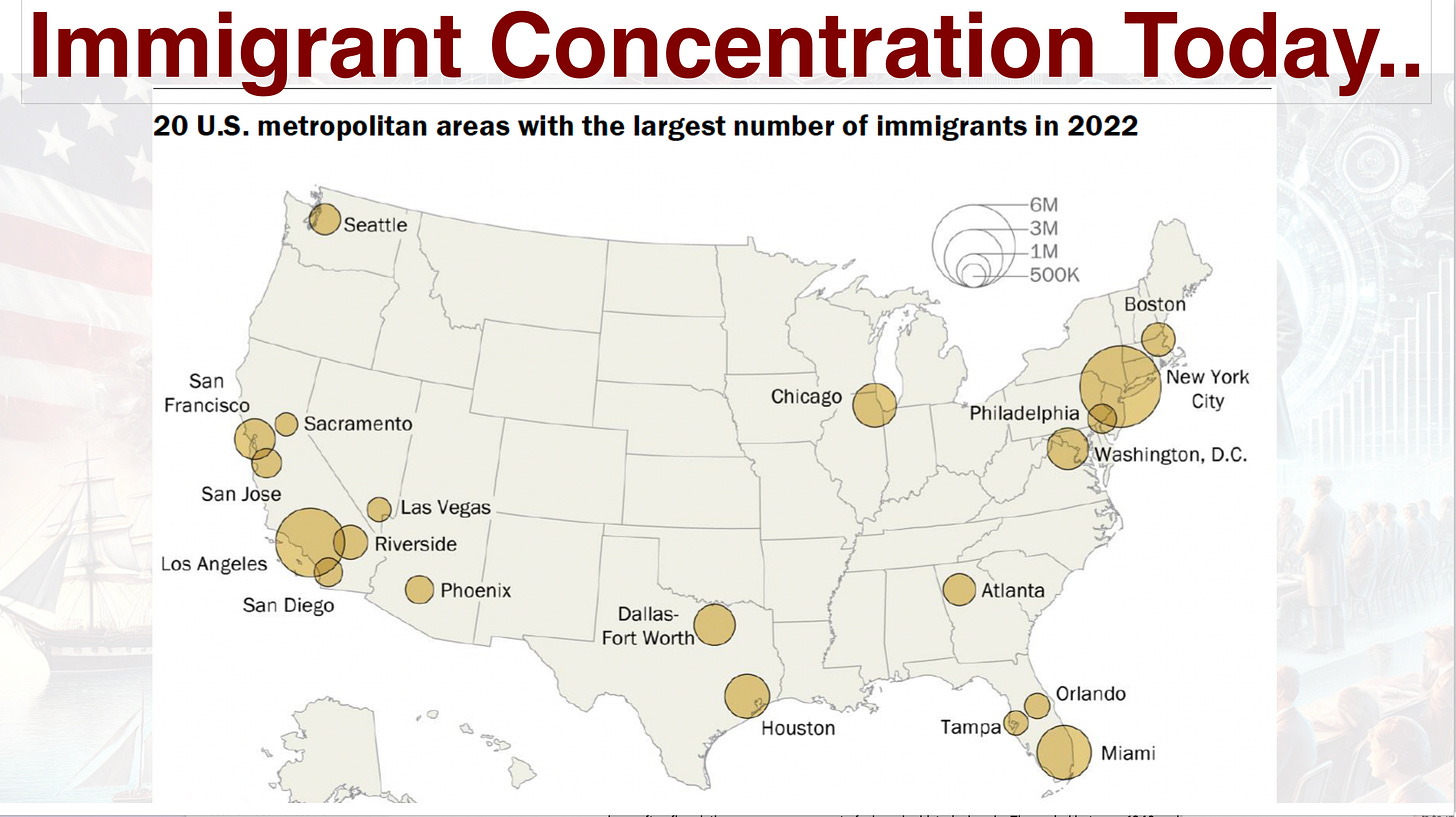

In short, no. The distribution of America’s population has followed patterns shaped by economic opportunity and geography. Major cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago have long served as magnets for immigrants due to job availability and established ethnic communities.

Yet America's population density, even in its most crowded regions, remains relatively low compared to other parts of the world. The so-called "megalopolis" from Washington, D.C., to Boston has a population density comparable to Britain or Germany—significant, but far from the density seen in regions such as the Pearl River Delta in China or the Tokyo metropolitan area in Japan.

Economic opportunity has played a major role in shaping migration patterns. Cities like Los Angeles grew rapidly due to the film industry, oil production, and wartime manufacturing. San Francisco and Sacramento developed as gateways to California's gold country, while Portland and Seattle emerged as commercial hubs for the Pacific Northwest. Meanwhile, cities like Houston and Oklahoma City thrived thanks to oil production and port access.

Some urban centers, such as Dallas, grew without an obvious geographic advantage. Instead, their success stemmed from aggressive promotion and development efforts, reflecting the broader American pattern of cities emerging where economic and social incentives align.

Conclusion

The United States has long defined itself a nation of immigrants, and the country’s demographic and economic growth has depended heavily on newcomers.

While political anxieties about immigration have often flared, so far these concerns have always been part of a broader historical cycle of ebb and flow.

The question for American politics today is whether optimistic rose-colored quasi-memories of America between 1940 and 1980—when immigration levels and the foreign-born population were unusually low—will turn out to have permanently shifted the American psyche and American identity away from the pattern of welcome established in 1620 that lasted until 1924, and resumed in 1965.

Readings:

Abramitzky, Ran, & Leah Boustan. 2017. “Immigration in American Economic History”. Journal of Economic Literature. 55(4) December: 1311-45. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Fjel.20151189>.

Abramitzky, Ran, Leah Boustan, & Katherine Eriksson. 2020. “Do Immigrants Assimilate More Slowly Today Than in the Past?” American Economic Review: Insights. 2(1) March: 125–41. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257%2Faeri.20190079>.

Crèvecœur, J. Hector St. John. 1782. Letters from an American Farmer. London: Printed for Thomas Davies and Lockyer Davis. <https://dn720206.ca.archive.org/0/items/bim_eighteenth-century_letters-from-an-american_st-john-de-crvecoeur-_1782_0/bim_eighteenth-century_letters-from-an-american_st-john-de-crvecoeur-_1782_0.pdf>.

Franklin, Benjamin. 1751. Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc. Philadelphia. <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-04-02-0107>

Lodge, Henry Cabot. 1891. “Lynch Law & Unrestricted Immigration”. The North American Review. 152(1) (May): 602-612. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/25102181>.

Wilson, Woodrow. 1893. Division and Reunion, 1829-1889. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. <https://archive.org/details/divisionreunion100wilsuoft>.

Back in teh 1970s, flying from England to Canada for the first time, I was amazed at how empty it seemed from the air, cities widely separated. Today, California from the air still looks rather empty compared to England and even most of Europe that I have visited. True, California appears water-limited, but that is because of the extensive, and rather primitive, use of water for farming. Reduce ag water demand and allow denser housing with better public transport, and California could increase its density several fold without problems, yet still maintain its attractive environment.

Love the "E pluribus unum" angle but, technically, isn't this CRT?