CONDITION: The Benefits of Central Heating!

I went to a Slouching Towards Utopia <bit.ly/3pP3Krk> panel at the SSHA Convention at the Palmer House in Chicago. It was 15F outside. I had the best possible discussants. And the video should be up in a couple of weeks.

A brief preview, in still images and words:

2022-11-19 Sa 14:00 PM - 15:45 CST: Clark 3 (Floor 7); Palmer House, Chicago:

Simone Wegge: This is an exciting session. We're here to celebrate the birth of this book: Slouching Towards Utopia. We have the author here in person. We almost are without empty seats. This is fabulous. Our discussants today are Barry Eidlin from McGill, Emily Merchant from UC Davis, Jari Eloranta from the University of Helsinki, and myself. We’re going to each get a chance to say something about Brae’s book. But first we're going to ask Brad himself to tell us.

Brad DeLong: Thank you very much . One of the great things about having finally managed to get this book out has been to discover how many friends I have, and how many friends the book has, and how many friends economic history has, and how many people are interested in thinking and thinking hard about what we know about the long run shape of human economic history. What are the stories we should tell ourselves?

[AS PREPARED:]

And let me stop there.

Simone Wegge: If one looks at the NBER working paper series, one sees Brad writing one entitled: The Shape of 20th Century History—perhaps that was one of the precursors of this book. And around that time in the year 2000, Paul Krugman wrote an opinion piece in The New York Times in which refers to Brad's book in progress.

So for getting it done, congratulations.

I still have the question of how the title cannot even change.

Brad DeLong: I could not think of a better one. I tried and tried. But you're William Butler Yeats is the best.

Simone Wegge: Slouching Towards Utopia made the New York Times bestseller list for nonfiction books in September, and their bestseller lists for books in business in the month of October. And then if you go to Amazon, you can see that this week, it was fifth in macroeconomics books on Amazon, and 13th in economic history books,

Brad DeLong: Actually higher than fifth. The fifth rank includes three different versions of Ray Dalio…

Simone Wegge: Amazon also tells us that the reading age is 13 years old, and grade 11 and up.

I beg to differ.

I made use of the audio version. And there were many times when I had to rewind to make sure I had gotten Brad's point.

Let me describe the subject matter and the breadth of the book a little bit more. The breath of economic and political events it covers is wide ranging. The geographic range is also very wide—he goes all over the world. It's very accessible to a very wide audience. There are no equations providing some complicated economic model. There's no tedious econometrics, nothing about instrumental variables, identification strategies, diff-in-diff estimation, etc, etc. cetera, et cetera, et cetera, which would bore the non economists of the world. The writing engages the reader. Brad has striking stories to tell you. Every other page, he comes up with some fact of describe some interesting socio-economic relationship, or uses a turn of phrase that is clever, and adroit. And this all keeps the reader reading on and eager to get to the next page…

FOCUS: In Which I Quibble wiþ Paul Krugman:

He has a very good case here. But I do not think it is as strong as he presents it, for there are huge things going on with safety premia as well. Thus there is much more going on, even in the long run, than fluctuations in real investment demand and in aggregate savings supply:

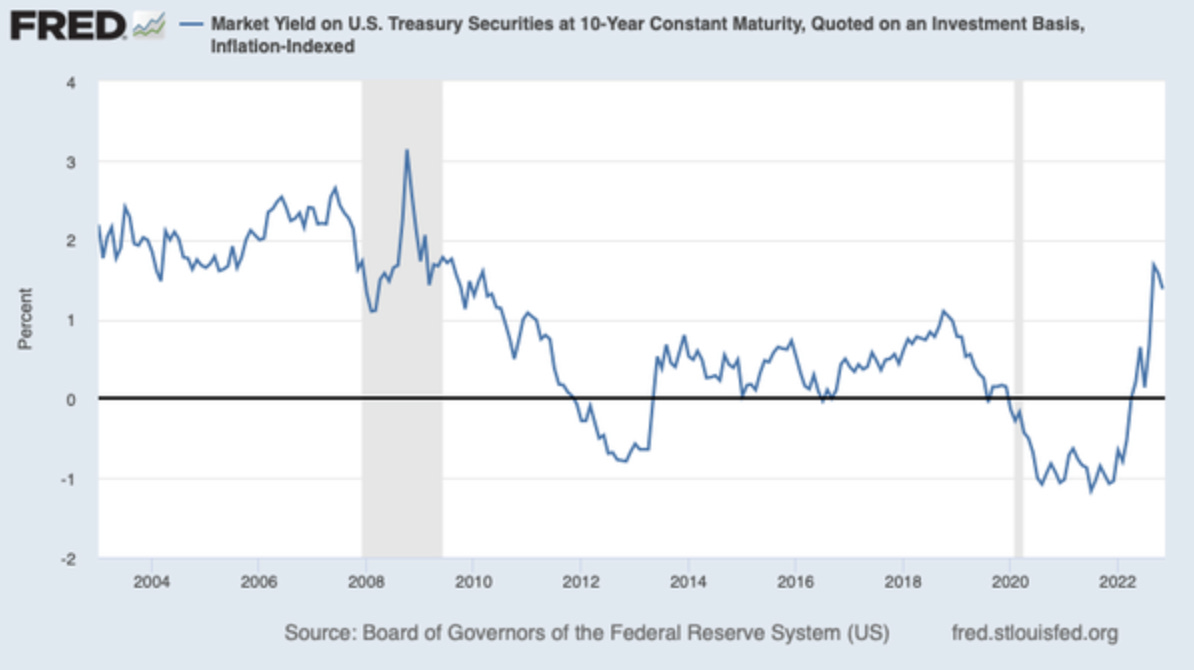

Paul Krugman: Why interest rates (probably) won’t stay high: ‘Here’s the interest rate on 10-year indexed bonds — bonds that are protected against inflation — since the 2000s:

After a long period in which money was almost free (at least if you were the government), we’re back up to rates close to those that prevailed before the 2008 financial crisis. But is the era of cheap money over?… Eventually, the boost to the economy from pandemic aid will fade away. And once that happens, we’ll probably be back where we were before the pandemic, with weak private investment demand holding interest rates down. Why will investment demand be weak?… The accelerator effect…. Investment spending will only remain high if we expect rapid economic growth. And what we know now doesn’t support that expectation…. Why the slowdown? Demography indeed plays a role…. Another important factor is that aforementioned midlife crisis in technology…. What all this suggests to me is that the era of cheap money is not, in fact, over. A few years from now, we’ll probably be back to a situation in which too much saving is chasing too few investment opportunities...

Our 10-year inflation-protected Treasury, security, the TIPS—which is market traders’ putting-their-money-where-their-mouth-is expectations of inflation—does not go back into the past millennium. But we can construct a very crude proxy for real Treasury long interest rates by subtracting the past year’s core inflation from the nominal 10-year Treasury rate. The two track each other well since 2004, save for the period immediately after the nadir of the Great Recession, when bond traders wrongly expected inflation to rise with recovery, and except for the past year, when the rebound supply-chain and now Russian attack inflation also has taken bond traders by surprise:

Looking further back into history, we see:

A period before 1965, when the ex ante 10-year expected Treasury rate was about 2.5%.

The post-1965 inflation, when the past year’s inflation is really not a good proxy for what ex ante inflation expectations were, and it is hard to figure out what real long-term bond rates were.

The Volcker disinflation of highly elevated long-term real interest rates from 1981-1985.

The post-Volcker “Great Moderation” period, in which the ex ante 10-year expected Treasury rate was about 3.5%.

The post-2001 period of increasingly despressed real interest rates—either the global savings glut, secular stagnation, or the global safe asset shortage, depending on your theoretical model.

The return toward pre-2001 normalcy that we see right now.

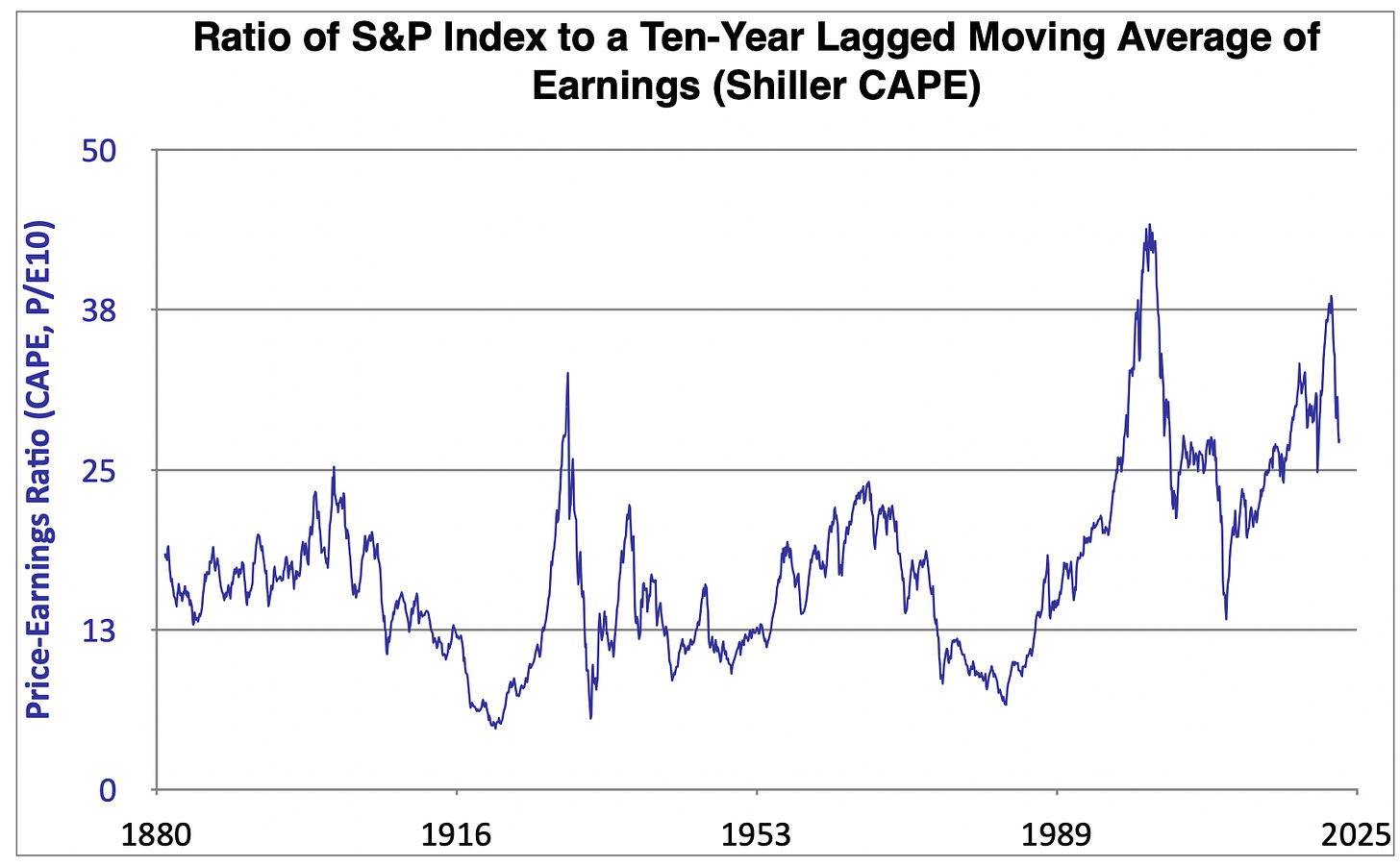

But what if we want to look not at nominal-safe assets—those that are useful as collateral and as safety anchors—but at profit rates, at real rates of return on risky assets? The best long-term measure we have is the earnings yield on Robert Shiller’s spliced-together Cowles-S&P Composite stock index series, which is the inverse of the profit rate:

In the 1990s, this Shiller CAPE index fluctuated between 14 and 44, with an average near 20, corresponding to a 5% real profit rate. Since the year-2000 collapse of the dot-com bubble, this Shiller CAPE index has fluctuated between 14 (at the nadir of the 2008-9 financial crisis) and 38 (at the recent market peak), with an average of 27 during the secular-stagnation era and 30 in the decade after the Great Recession:

For the part of the decade of the 2000s before the Great Recession, the ratio corresponds to a risky-profit rate average of 3.9%/year, compared to a 10-year real TIPS rate of 2.3%, and a short-term Treasury-bill real rate of 0.5%/year.

For the decade after the Great Recession, the ratio corresponds to a risky profit rate average of 3.3%/year, compared to a 10-year real TIPS rate of 0, and a short-term Treasury-bill real rate of -1.5%/year.

The post-2010 risky-real profit rate averaging 3.3% is indeed sustantially elevated below the 1990s average risky profit rate of 5%. But I find it very interesting that the profit rate held up so well: long nominal-safe real rates fall from 3.8% in the 1990s to 0% in the 2010s, while the fall in the risky-profit rate is only 2/5 as large in percentage point terms.

There are important things going on that are not just real investment demand and savings supply.

MUST-READ: Enlightened Economist Prize:

Diane Coyle: Enlightened Economist Prize 2022—The Winner: ‘It’s always much harder to select a winner than to decide on the 10 (occasionally 12) books on the longlist, and somehow harder than usual this year. For I’ve decided there are two that have the combination of interest, distinctiveness and excellent writing I’m looking for. So, with the usual caveat that this is an entirely personal decision based on what I happen to have read, my own interests, (and no doubt my mood at the time), I’m offering a free lunch to both Brad DeLong for Slouching Towards Utopia and James Bessen for The New Goliaths. Congratulations to both!

Oþer Things Þt Went Whizzing by…

Very Briefly Noted:

Tom Ferguson: From Normalcy to New Deal: Industrial Structure, Party Competition, and American Public Policy in the Great Depression: ‘International Organization Vol. 38, No. 1 (Winter, 1984), pp. 41-94 (54 pages)…

Cosmo Rodewald: Money in the age of Tiberius…

Noah Smith: Are the UK, Japan, and Italy "undeveloping countries”?: ‘The danger of real economic decline…

Gary Clyde Hufbauer & Megan Hogan: CHIPS Act will spur US production but not foreclose China: ‘More US semiconductor fabrication plants… R&D will be accelerated… advanced chips and chip-making machines will be denied to… adversaries….. The Act will not make a material difference to US chip supplies in the next two or three years.... US self-sufficiency is an illusion.... Continuing to prioritize advanced chip production… is the most efficient course of action...

Rebecca Choong Wilkins: China’s Xi Sends Joe Biden an Olive Branch…

Andrew Gelman & Cosma Rohilla Shalizi: Philosophy & the practice of Bayesian statistics: ‘The most successful forms of Bayesian statistics… accord… with sophisticated forms of hypothetico-deductivism. We examine the actual role played by prior distributions in Bayesian models, and the crucial aspects of model checking and model revision, which fall outside the scope of Bayesian confirmation theory…. Clarity about these matters should benefit not just philosophy of science, but also statistical practice…

Nathan Baschez: Writing with Machines: ‘How AI will—and won’t—change writing…. My goal right now is to try and identify the ways that AI can most fundamentally transform the writing process. The more different and valuable it is, the better. If we’re just like Google Docs with a bit of commodity AI slapped on, it’s not going to be very interesting…

Matthew Yglesias: Getting back on track with the Latino vote: ‘You were trying to get to a diner… but you’re actually at a pizzeria, because you made a mistake several steps ago…. Now you… can eat some pizza or you can break out your map and make your way to the diner. But… don’t… pretend… stroll into the pizzeria, and order pancakes. This is what Democrats seem to me to be doing with the Hispanic vote…

¶s:

Rana Faroohar: Crypto: new asset, old problem: ‘The demise of FTX mirrors any number of traditional financial meltdowns in the past: ‘This time still isn’t different when it comes to the financial sector and risk…. The details… mirro… the 2008 financial crisis, and other periods of financial speculation…. It was an internal trading operation, Alameda Research, making opaque deals that set the collapse in motion. Plain vanilla lending or market making becomes boring; the temptation for greater profit and risk via trading looms large…. Alameda was able to make its crypto trades on the FTX platform…. This sort of conflict of interest came to the fore several years ago during the Goldman Sachs aluminium hoarding scandal of 2013. It is also omnipresent in the tech platform arena…. But it is even more problematic in the fintech space, which blends all the risk of complex financial transactions with… algorithmic opacity…. Once it became clear that the company was in trouble, there was a classic run...

Sam Hammond: Why I'm not (exactly) an Effective Altruist: ‘Coase & Ostrom >> Bentham & Pigou: My own contribution to this debate is to argue that, contra the growth-equity trade-off, robust social insurance programs are both a condition and accelerant of sustainable economic growth. Yet the normative logic of social insurance is Paretian, reflecting the contractarian imperative to efficiently compensate the potential “losers” from creative-destruction, and thus isn’t merely instrumental to growth. The preference-neutrality and positive-sum logic of a Pareto improvement makes it easily confused with utilitarianism, but the two have quite different implications. Utilitarianism is top-down…. Paretians, in contrast, start with the bottom-up process of exchange and transaction…. This is at the heart of bargaining theory and how de jure property rights emerged in the first place…

Eric Levitz: Is Effective Altruism to Blame for Sam Bankman-Fried?: ‘Caroline Ellison, an SBF associate and CEO of Alameda Research, put the point more accessibly in a now-deleted Tumblr post. “Is it infinitely good to do double-or-nothing coin flips forever? Well, sort of, because your upside is unbounded and your downside is bounded at your entire net worth. But most people don’t do this, because … they really don’t want to lose all of their money. (Of course those people are lame and not EAs; this blog endorses double-or-nothing coin flips and high leverage.)” In other words, according to their own public statements, Bankman-Fried and Ellison both believed that they had a moral obligation to make “double-or-nothing” financial bets over and over again—even though this would almost certainly lead to financial ruin eventually—because there was a small chance that they would just keep winning such bets, and thereby save humanity. And some of the world’s most reputable investors handed them billions of dollars anyway…

Michael Pettis: ‘The easiest way to convince someone else of a lie is to believe it yourself: Because I've been devouring books and papers on financial history for over 30 years, I thought understood from fairly early on how risky the crypto space was and how likely to be filled with scammers and pyramid schemes. The emerging picture of what went wrong suggests the crypto empire was a mess almost from the start, with few boundaries, financial or personal. And yet I still find all these article about SBF fascinating because they add a lot to the historical accounts. For example I had always assumed there was a sharper difference between the scammers that took advantage and the unsophisticated victims they exploited. But from these accounts it occurs to me that the self-delusion was so deep that it drove the scammers as much as it drove the victims…

I think people have it backwards on effective altruism. People choose their religion and belief system because it lets them do what they want to do. If your kink is guilt tripping other people for enjoying sex, then you choose a sexually repressive religion. If your fun is killing or torturing people for [Insert Reason Here], you have a broad choice of religions and philosophies that you can adopt that will encourage you in your proclivity and grant you suitable approbation. If your wish is to accrue massive wealth, take on big risks and ignore the problems of the present, you can choose effective altruism and both indulge yourself and feel good about it.

Rolling double or nothing indefinitely only works if you are immortal and have infinite resources. Taking on huge risks makes sense for people with a family trust, a good supply of f--k you money or a sexy bod admired by venture capital bros you can fall back on. Ignoring the problems of the present can work within one's individual life span, for example, Louis XV died on his throne well loved.

Unless Krugman want to go into the financial advice business, why try to predict future real rates?

Why do macroeconomic policy makers need it.? Now for fiscal policy, yes becasue we don't want the Government investing in things with negative NPV.