Discover more from Brad DeLong's Grasping Reality

Inflation Debate Talking Points

For American Lyceum event wiþ Garett Jones, John Taylor, Tim Kane, & Brad DeLong :: recorded 2023-04-27 Th

American Lyceum: <https://theamericanlyceum.org/>

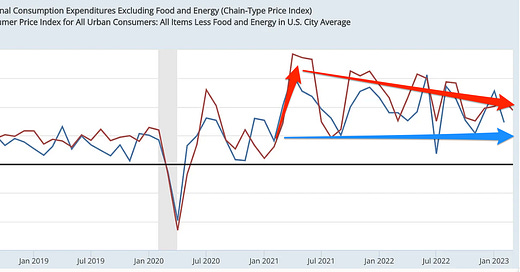

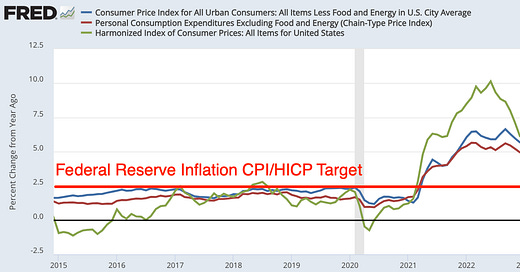

The general belief that the short-run Phillips Curve was flat meant that the sheer magnitude of the reopening inflation came as a substantial surprise to many:

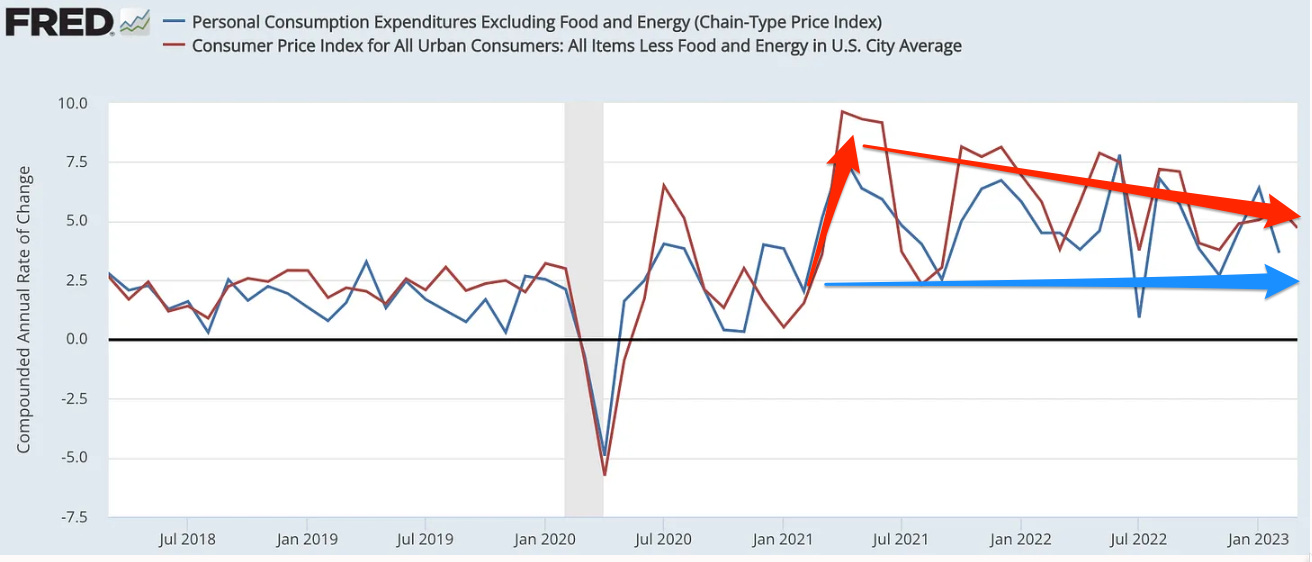

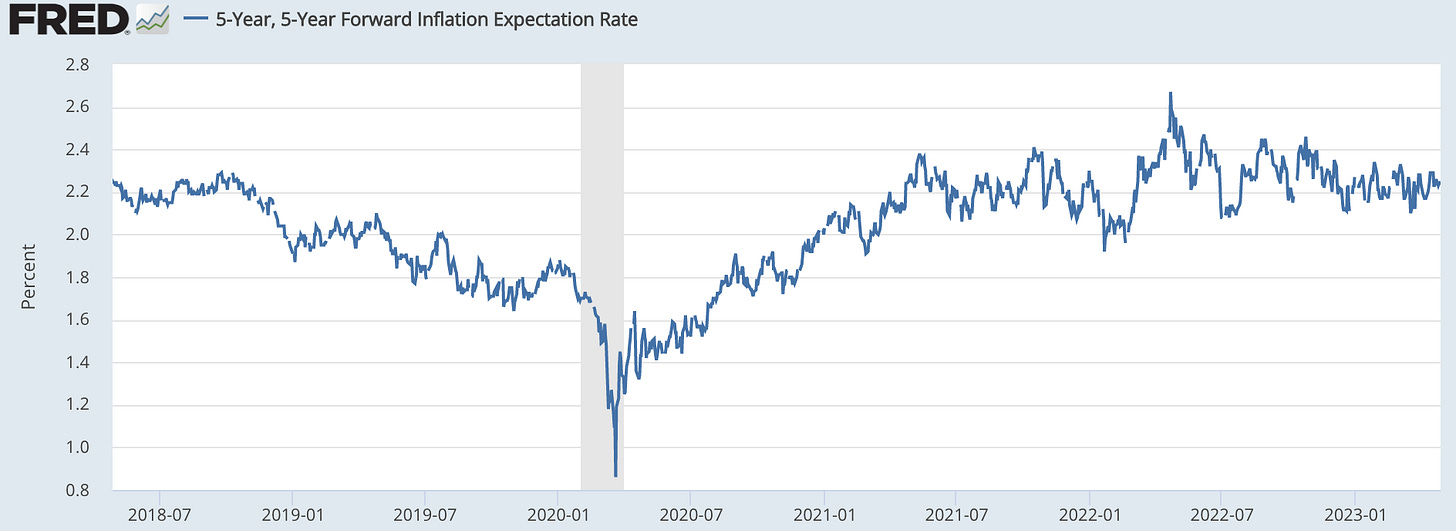

And yet throughout the inflation medium-term expectations of future inflation in the bond market remained nailed to where they need to be for the Fed to costlessly attain its 2%/year target well before 2030:

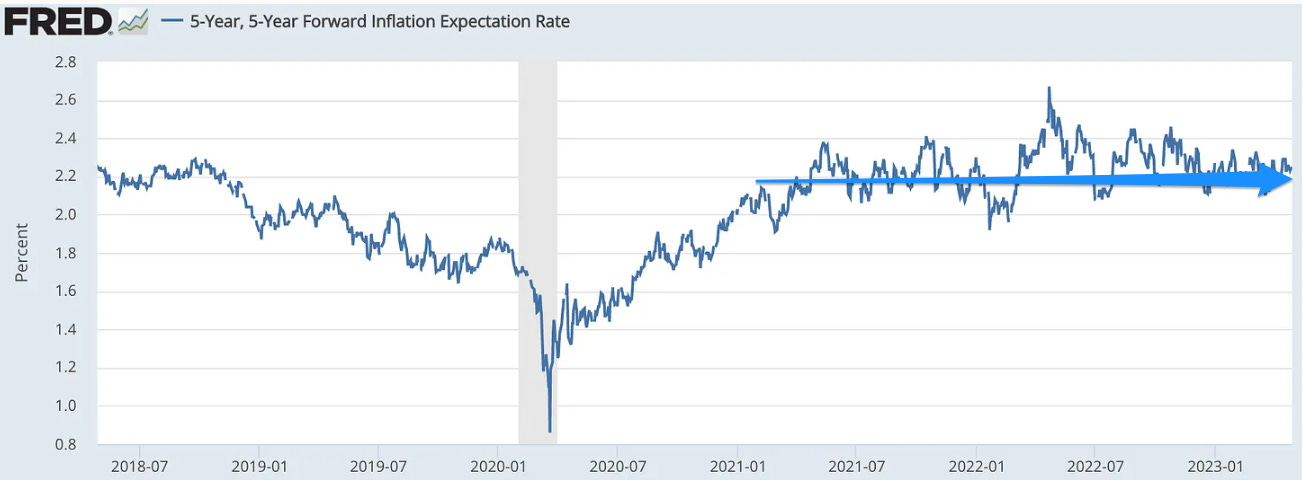

And so:

The Fed should keep doing what it has been doing:

I see the past two and a half years as having had a very surprising burst of inflation, much larger than the Federal Reserve or many other commentators were expecting, coming out of the economic depression caused by the plague.

However, throughout, medium-term inflation, expectations have been and continue to be nailed to what they need to be for the Fed to hit its medium-term inflation target without undue unemployment.

Had the Fed moved earlier, we would not have had as rapid and complete a recovery from the plague depression—America would be poorer, and the market's von Hayekian crowdsourcing would be much less effective at boosting economic growth.

I am profoundly disappointed—but not with the Fed:

Rather, I am profoundly disappointed with the congressional leadership:.

Schumer, McConnell, McCarthy and Jeffries should be providing much more backup.

Janet Yellen and Jay Powell need backup as they wrestle with financial stability issues.

The congressional leadership is not providing it.

The relative-price movements—the responses of wages to labor shortage, and of prices to bottlenecks—we have seen since the start of 2001 are strongly, strongly positive-sum:

They are necessary if the market economy is to do its von Hayekian crowdsourcing-solutions-to-resource-allocation job:

The supply shocks of Putin’s attack on Ukraine have deranged the global economy substantially.

The associated inflation that has accompanied those relative-price movements is zero-sum.

The associated inflation will remain zero-sum unless it feeds through to elevated expectations of medium-term inflation in the future.

Such elevated inflation expectations would bring with them a temporary rise the natural rate of unemployment, and so be a substantial loss.

Since there are no signs of any such shift in medium-term inflation expectations, there are no net downsides—and very powerful upsides—to the policy the Federal Reserve has followed.

So far, Jay Powell and company have got this.

Now you can argue that things might have worked out differently:

You can argue that the Federal Reserve has been lucky.

You can argue that the Fed’s moving to tighten “late” ran the risk of generating a temporary rise in the natural rate of unemployment via the medium-term expectations channel.

Possibly.

But the Fed’s moving to tighten “late” has not done so.

And for the Federal Reserve to have moved earlier would have incurred risks of generating another ænemic and grossly unsatisfactory recovery—like that under the Obama administration.

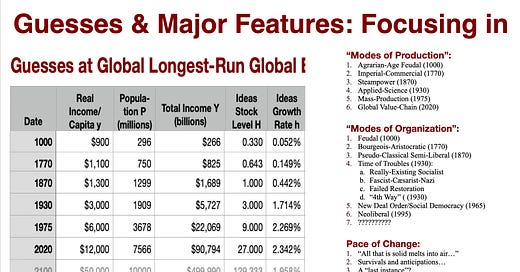

I do find myself running into lots of people these days who do not understand the von Hayekian microeconomic argument that the past three years’ inflation has been a beneficial outcome that the market commanded because we needed relative prices to respond quickly and substantially ifor the market to do its crowdsourcing resource-allocation, business-model experimentation, and productivity-generation job.

Yes, the logic of von Hayekian microeconomics contradicts the logic of von Hayekian macroeconomics—remember that von Hayek rejected what he called Irving Fisher’s “dogma of the stable price level” and wanted deflation at 4%/year so that the economy could hit a stable nominal GDP argument.

There are good reasons Milton Friedman called von Hayek “a true genius, but not in the fields of monetary theory and policy”.

A straightforward linear Taylor rule goes awry whenever the economy is in a state in which interest rates are near the zero lower bound:

Coming out of a depression with interest rates at the zero lower bound, if you move late you can move fast and catch up.

But if you move early and so send the Wicksellian neutral nominal rate back below zero, there is no way to repair the mistake.

One kind of mistake takes you over the cliff, while the other kind leaves you on solid ground.

This asymmetry adds an extra “optionality” term to the Taylor Rule for monetary policy.

That extra “optionality” term means that moving “late” and then fast is in fact optimal.

Was any damage done to the economy by the Fed’s moving late and fast?:

Yes: the destructive crypto-grift bubble of 2021-2022, which redistributed a lot of money to bad actors and consumed a huge amount of electricity was a real economic cost.

But on the other hand we got a much more rapid approach to full employment.

A full employment economy is:

a richer one, for more people are employed.

a faster-growth one, as more profits and poured into investment.

A faster-growth one, as more knowledge is gained via business-model experimentation.

A more efficient one, as the von Hayekian crowdsourcing-solutions-to-problems-of-production works much better when resources are taught than when they are slack.

The downside of rapid approach to full employment would be if that raised medium term inflation expectations, and thus temporarily raised the natural rate of unemployment.

That temporary increase in the natural rate of unemployment would mean that the period of fast employment growth would be followed by a period of sub-par high-unemployment stagflation.

But there are exactly zero signs that that channel is in operation.

There is no sign that rapid approach to full employment has done anything to reduce the Fed’s credibility, raise medium-term inflation expectations, or temporarily raise the natural rate of unemployment.

You have been prescient and consistently accurate questioning great influencers screaming the Fed was behind the curve. Getting to full employment from 14.7% in April 2020 is an extraordinary achievement and once again you are so appropriately asking why aren’t our senators applauding. This is after all about people and putting people first.

Bingo! on each point you've made, especially the one about the "optionality" in the Taylor Rule. (If I may say so, at my own expense, you have underpriced your blog!). Another thing, if I may, about the Taylor Rule. Unemployment can go up, say from 3.5% to 4.5%, in three ways. 1) Layoffs 2) Improved participation rate 3) Mix of (1) and (2). If you set aside the inflation segment of the Rule for the moment, it would recommend only one course of action for all. But the underlying economy is different in each scenario. An economy where unemployment is up due to mass layoffs is different from one in which unemployment is up because people are drawn into the labor force when jobs become easier to find. They are counted as unemployed during search.