Japan's Economy: Present, Past, & Future

A DRAFT of a preface to the Japanese-language edition of "Slouching Towards Utopia"...

A DRAFT of a preface to the Japanese-language edition of "Slouching Towards Utopia"...

The great Simon Kuznets, winner of the Economics Nobel Prize in 1971, may or may not have been the first person to say: "There are four kinds of countries: rich countries, poor countries, Argentina, and Japan". Whoever said this was right: Japan's economic experience since the late 1800s is the most impressive and the most heartening thing in all the economic history of the 20th century. And the political history of Japan since 1870 has a very good middle and end as well, after a beginning it which it unfortunately catches the virus of modern imperialism from the European countries that break open Tokugawa-era isolationism. The future of Japan? That is large in the hands of my Japanese readers and their compatriots.

Japan is the prime example of one of the four patterns followed by 20th century economies. It is a remarkable example, a heartening story, and an impressive accomplishment.

It has spurred many others--South Korea, Taiwan island, Hong Kong, Singapore in the first wave; Malaysia and Thailand in the second; and now coastal China and Vietnam in the third--to successfully accomplish the very difficult task of becoming rich by deploying modern industrial and post-industrial technologies. So one would think that Japan would play a very prominent role in an economic history of the 20th century. And yet "Japan" appears on only 49 of 580 total pages--less than half of what one might think of as its appropriate share. For this I apologize: in spite of the attempts of Henry Rosovsky and others, I learned less and now know less about Japan than I should, and I found myself focusing in the writing on stories and episodes where I was overwhelmingly confident that my insights were accurate and worthwhile.

But this skimming lightly over Japan in this book is not a defect for a typical Japanese-language reader, who knows more about Japanese economy and history than I do and is likely to wince at my errors and misjudgments. The principal use of the book for the typical Japanese-language reader is as a baseline to use for understanding the remarkable story of Japanese economic history since the beginning of the Meiji Restoration.

And what an astonishing story it is!

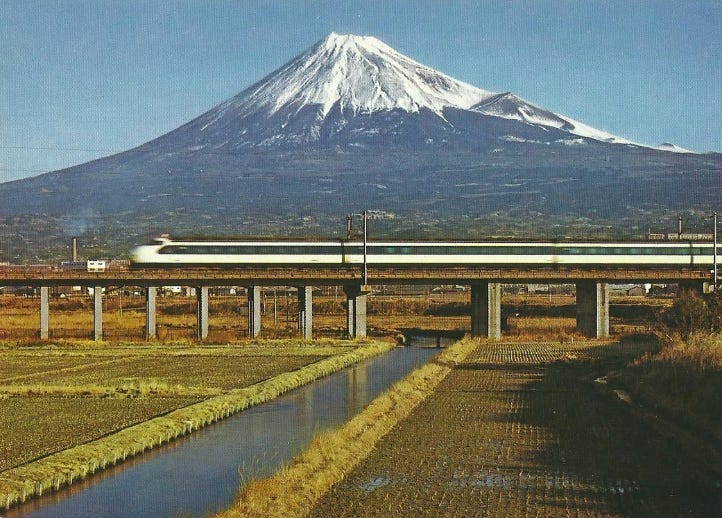

For Japan, the long 20th century began with the country establishing itself as an industrial force, a process that accelerated with its victory in the Russo-Japanese War. That conflict signaled Japan's arrival as a modern imperial power in East Asia, reshaping the geopolitical landscape, providing Japan with additional opportunities for economic growth and development, and focusing the attention of many on Japan as showing a way that countries could escape the role into which the North Atlantic was trying to cast them as poor hewers of wood and drawers of water. But as bright as the pre-WWII period was for the economic development of Japan in productivity, trade, and macroeconomic stability—Japan's successful avoidance of the Great Depression could have taught powerful lessons to the rest of the world, had that success been registered and studied—no other economy up until 1960 was able to even begin to follow in its footsteps.

After World War II Japan showed the world how great the potential for economic growth could be, and how that potential could be realized. The enormous death and devastation rained down on the entire Japanese population—military and, more so, non-military—by American strategic bombing the war gave way to a period of unprecedented economic growth that was the Japanese economic miracle. "Slouching Towards Utopia" situates this recovery and boom within the broader context of global economic trends, including the Cold War's influence on trade policies and technological exchange. For Japanese readers, this comparison not only highlights the unique aspects of Japan's economic policies but also integrates Japan's experience into the larger narrative of post-war recovery and growth experienced by other industrial nations.

And after 1960 the lessons of Japan's extraordinary economic success began to be learned outside. It is not overstatement to say that emulation of the Japanese model, allowing for local conditions, was the key link in making the sun of economic growth rise so conspicuously and shine so brightly along the whole Far East that is Asia's Pacific Rim. The combination of government intervention, private sector innovation, and stakeholder-centered management was a very sharp counterpoint to the more laissez-faire approaches that took hold in the North Atlantic, especially after the Neoliberal Turn of the 1970s. Japanese readers will recognize how distinctive and effective the Japanese approach of both guidance by an embedded-yet-autonomous state and immediate profit-driven decision-making by the market was at national economic management. And the contrast with the exaltation of more laissez-faire oriented policies under the Neoliberal Order in the North Atlantic will be clear.

But the changed global order after the Neoliberal Turn was not one in which Japan could continue to flourish economically as much as it had before. The book provides considerable insight into the turn in the 1970s away from the social-democratic New Deal Order to the Neoliberal Order, and the resulting disruptions of the global economy that did so much to impose substantial economic drags upon the Japan. The Nixon shock of 1971. The oil shocks of 1973 and 1979. The extra shock administered to the global economy by a U.S. Reagan administration that seemed out of its depth—the explosion of U.S. government deficits and the consequent rise of the dollar in the early 1980s and the failure of the U.S. to keep its deficit-reduction commitments made in the Plaza Accord in 1985.

These factors more than set the stage for the collapse of the Japanese real-estate market in 1991. The burst of Japan's asset bubble in the early 1990s and the subsequent "Lost Decade" are critical to understanding the vulnerabilities and resilience of the Japanese economy. The subsequent period of secular stagnation that substantially reduced Japan's rate of economic growth. Indeed, Japanese per-capita economic growth would remain profoundly unsatisfactory until well after the launch of Shinzo Abe's "three arrows" macroeconomic policy reforms in 2012.

In the most recent decades, the narrative of "Slouching Towards Utopia" explores the implications of globalization, the rise of the information economy, and the hyperfinancialization of global markets. For Japan, these phenomena have presented both challenges and opportunities. The book provides a background framework for examining how Japan's economic policies have adapted to the shifting paradigms of global finance and trade.

The trajectory of Japan's economy in the future is an issue of great importance and a subject of keen interest and speculation. Given Japan's aging population, its innovative approaches to technology and health care, and its strategic positioning within Asia, drawing the right lessons from the past century are invaluable. Japan's future economic path must involve navigating tensions between national policy priorities and global economic pressures, with potential leadership roles in technology, environmental sustainability, and multilateral trade agreements.

Japan was derailed in the 1980s from the possible future in which not California's Silicon Valley but Japan's Greater Tokyo was at the leading edge of the global economy. It took on an economic role in manufacturing much like that of Germany, as the world leaders in taking pains to produce commodities of extremely high quality and reliability if not able to produce the most innovative or to push the product innovation—as opposed to the process development—frontier out as far and as fast as possible. And outside of manufacturing the Japanese economy remains high-touch rather than unusually efficient.

But this can very easily be the springboard for much more than satisfactory economic growth over the next several generations, especially given the large numbers of talented and industrious people born elsewhere for whom the opportunity to work and live in the built environment of with the accumulated industrial capital stock of Japan would be of enormous value.

Remember: post-bubble Japan remains an amazingly productive economy in world context. It ranks significantly higher in most quality-of-life metrics than it does in income comparisons. Japan today has many lessons to teach the rest of the rich world on living wisely and well. The differential deadliness of the COVID plague in Japan and the United States should make all of us Americans think very hard about the societal choices that we have been making, and reconsider whether in fact Japan might not in fact be #1.

References:

DeLong, J. Bradford. 2022. Slouching Towards Utopia: The Economic History of the 20th Century. New York: Basic Books. <https://archive.org/details/slouching-towards-utopia>.

Haass, Richard. 2024. "Blocked Sun, Rising Sun." Home & Away. April 12. <https://richardhaass.substack.com/p/blocked-sun-rising-sun-april-12-2024>

Taylor, Alan. 2014. “The Argentina Paradox: Microexplanations and Macropuzzles”. NBER Working Paper No. 19924. February. <https://www.nber.org/papers/w19924>.

Yglesias, Matthew. 2012. "The four types of economies and the global imbalances." Slate, April. <https://web.archive.org/web/20230412215407/https://slate.com/business/2012/04/the-four-types-of-economies-and-the-global-imbalances.html>.

I believe there's a typo of some kind here:

The enormous death and devastation rained down on the entire Japanese population—military and, more so, non-military—by American strategic bombing the war gave way...

I think maybe that should be "strategic bombing DURING the war", or "IN the war"?