Lecture Highlights: Why Are People Watching Me (Try to) Program in Python?

Plus MOAR, as I provide (some of) this week's lecture highlights: How do we shift education to cope with technology? This has been a problem since the year -3000, if not before. Are there useful...

Plus MOAR, as I provide (some of) this week's lecture highlights: How do we shift education to cope with technology? This has been a problem since the year -3000, if not before. Are there useful parallels between medieval education and modern programming skills? What were the disastrous unintended consequences of agriculture on human health? How much of our economy is devoted to hacking our hunter-gatherer brains?…

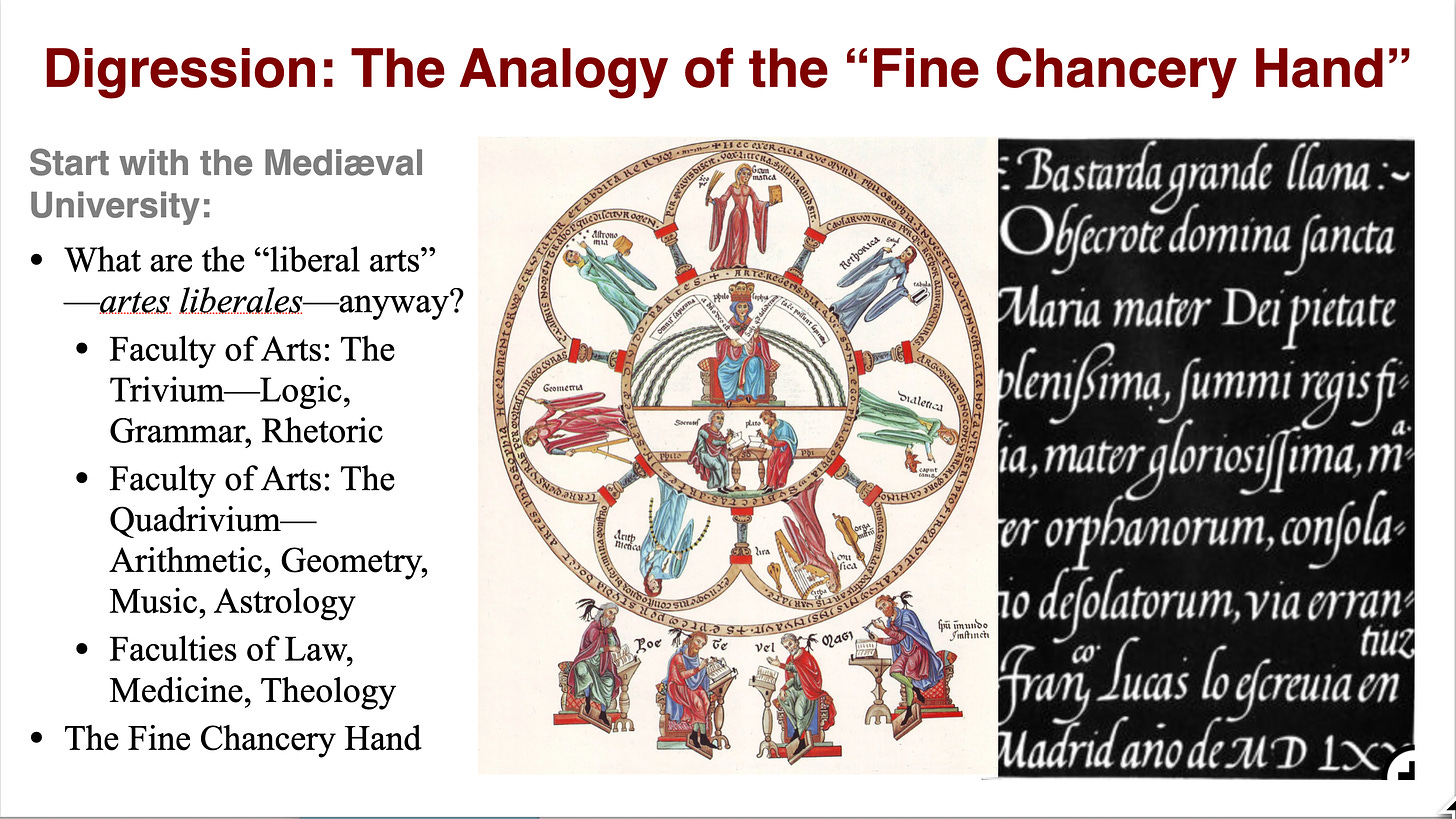

Basic Programming Today as a “Hidden Curriculum” Analogous to the Mediæval Fine Chancery Hand:

Me: In the Middle Ages, people were taught the liberal arts--the artes liberales—which consisted of a verbal side: logic, grammar, and rhetoric--how to think, write, and argue. The four STEM disciplines of the day were arithmetic, which included algebra; geometry, which included surveying and land demarcation; music, which included the very beginnings of trigonometry as well as music theory; and astrology because it was important to learn how to cast horoscopes. (A weird selection of STEM disciplines, but it was the Middle Ages, after all.) After getting the foundation in those, you'd go off and do your professional education--law, medicine, or theology.

The point of this curriculum was not to create a well-educated, well-rounded person who was properly and fully human. In a Middle Ages in which almost everyone else was a peasant, craftsman, merchant, soldier, or boss, university education was highly pre-professional. University students were people who did not think they had a good place as a craftsman or merchant, or were not any good as potential soldiers. They went to the university because they were a person who was free--both in the sense that nobody was their boss and in the sense that they had no connections in society feeding them every day. They had to live by their wits. Hence they needed to learn the skills—to learn the "arts" in the sense of "the art of war"—so that they could persuade other people to pay them for what they did.

And if you could write, persuade, make logical arguments, calculate, survey, lead musical events, and cast horoscopes to forecast the future, you could probably convince a local thug with a spear that you'd be a good accountant, propagandist, or bureaucrat.

So: “liberal arts” really means “skills that are useful for a free person—one who does not have a place in the hierarchy of domination, submission, provision, and exploitation—who has to figure out how to live by their wits in a mediæval society”.

But there was another skill people learned, a "hidden curriculum" . It was to write with a fine chancery hand--to be able to write something with a goose feather and bad slow-drying, blotting, and spattering ink that was easy to read.

For the duration of your careers, I think there's going to be a similar skill--learning how to do quick and dirty programs with a computer. Just as half the point of the medieval university was learning to write so people could read what you had written: training the hand muscles was a key point. And so, analogously, we suspect that training your programming muscles is likely to be key for you all.

You can work on your machine or on Berkeley's datahub, which has the advantage that lots of people are supposed to keep it up and running, but the disadvantage that it's underfunded..

MOAR Highlights:

Recommended Course: Sex, Death, & Data:

Me: So, what was the best class any of you have been to so far this semester?

Student: It's similar to this one—Sociology C126: Sex, Death, and Data. We talk a lot about mortality rates and inequality—very interesting alongside this course.

Recommended Course: Financial Accounting:

Me: How about the most surprisingly good course that any of you have been to so far? The class where you weren't expecting much because it's a requirement, but it turned out to be surprisingly good.

Student: Financial Accounting. UGBA 102A.

Me: Tha tcan be absolutely fascinating—people trying to exercise some kind of control over what is actually going on in a large bureaucratic organization with limited abilities to clue themselves in to what is really going on.Trying to establish management systems so that, as long as the numbers are okay, we can leave the subsystems alone. But if the numbers are not okay, something very much needs to be done, and someone needs to rapidly figure out what.

The “Homework Apocalypes”, MAMLMs, & the Needed Next Transformation of the University:

Me: Tangentially relevant to but not part of this course, I flagged a piece that crossed my screen this week by Wharton professor Ethan Mollick. He has been attempting to grapple with what the coming of MAMLMs—GPT LLMs, or what people are calling "AI"--will mean for the university.

First, I insist that it is not “AI”. While it's certainly artificial, it definitely is not “intelligence” as we know it. The word "intelligence" is marketing-speak, aimed at clouding the minds of investors and customers. It is MAMLMs: Modern Advanced Machine-Learning Models.

What surprised me in Mollick’s piece was not that it said that doing the homework is good—because it is; it does effectively train your brain for certain kinds of conceptual tasks. What surprised me in Mollick’s piece was not that the coming of MAMLMs in the form of GPT LLMs—General-Purpose Transformer Large-Language Models—was having a bad effect on getting people to do the work.

What surprised me in Mollick’s piece was that this “homework apocalypse’ already happened ten years ago.

Over the course from 2008 up to the present, the fraction of people doing assignments at Rutgers by simply looking up the answer on the internet, copying and pasting, and hoping they get things right went from around 10 percent to around 75 percent. This had appalling consequences for how people were able to do on exams.

Now, exams are not real life. Maybe students, plus their machines and internet access, were more effective at doing relevant real-world cognitive tasks in 2022 than they had been in 2008. Maybe were just not as effective at the artificial and unrealistic exercise or writing in-class exams without access to any books, machines, or networks. While people have been taking closed-book in-class exams since the University of Paris started in the 1000s, that is not how one typically does cognitive work today. That is how one did cognitive work in the 1300s if one was a clerk in a provincial bishop’s or a judge’s office back then. But that as long ago and far away.

In the modern context, in-class exams are not a kind of cognitive task you will ever perform again in your lives. So perhaps it doesn't mean much.

But perhaps the fall-off in exam performance does mean something. I think it probably does mean something. Thus I think we on this side of the podium to be making a much better effort to get you all to do the work.

Mollick believes that universities are not coping because of two illusions:

The "detection illusion"—teachers believe they can judge whether things are AI-created or not

The “look-up illusion”—students think knowing how to look something up is good enough. But knowing how to look it up is the first step. Asessing it, changing it, revising it, reworking it, and using it as an input for your cognitive processes rather than an output—that's the way to actually turn you and your tools into something much more productive.

We need to reimagine how we teach and learn. But we have done this before. We did it in the year -3000 when we figured out how to write things down, and your thinking went from just what was in your memory to memory plus the reminder nudges given by weird symbols carved into clay. We did this around -800 when we went from having mere accounting records to having stories, descriptions, and narratives. Then came printing. Other technological revolutions since. We have figured out how to adapt.

“Lecture” originally meant that I would be up here, nose down in a book, dronily reading it aloud to you, as it made much better use of the very scarce resource that was a very expensive book for you all to listen to it being read aloud at 100 words per minute than for all 75 of you to read the single existing copy in succession at between 200 and 500 words per minute. And the idea of making 75 copies at a cost of 20 person-years of work so you each could have a copy—inconceivable.

That is not what we do here. Think about that—how it is still called a "lecture", but is a very different animal.

The Invention of Agriculture as World-Historical Mistake:

Me: What do you remember from last time?

Student: Femur sizes over time.

Me: Yes. We estimate adult heights from the length of femers in graves—the long bone in the leg, the one most likely to survive. And what specifically about femurs over time?

Student: What it tells us about agrarian-age standards of nutrition.

Me: Yes. The idea that typical agrarian-age peasants and craftsmen were 3.5 inches shorter than we are is a huge deal. The 2-inch difference between agrarian-age working and upper classes is also something I find astonishing every time I look at it. Post-agriculture agrarian-age societies as very poor, at least in a biological fitness sense, and very vicious in their structure as societies of domination. This leads UCLA's Jared Diamond to cnclude that agriculture was a mistake—the biggest mistake in the history of the human race, he says.

It was not a mistake for the first few generations to farm, however. They saw a huge increase in food abundance and a decrease in required work. The first few generations were better nourished, had more energy, and their children were better fed, so more children survived—both because of better nutrition, and because the gatherer-hunter lifestyle requires carrying neonates and toddlers around for long distances, hard on the mother hard on the child.

But because, initially, agrarian-age life was easier and more babies survived, the population grew, and so the agricultural niche filled up. Population kept growing until living standards were back down to what they had been during the hunter-gatherer age. But because life was easier as a farmer than it had been as a hunter-gatherer, the population kept growing beyond that point. And so, with resource scarcity, living standards declined below gatherer-hunter norms. Children became were so malnourished that they were killed by the common cold. Potential mothers became so skinny that ovulation became hit-or-miss. You were a lot less fit as a peasant or craftsman than your ancestors had been as hunter-gatherers, in a biological sense, because life was easier.

The balance sheet, indeed, is probably negative. You would probably rather be a typical hunter-gatherer than a typical peasant or a low-level craftsman in human society anytime from -8000 until maybe 1930.

Scary.

Scary especially in a course dedicated to economic growth, because it suggests that from -8000 up until 1930, well, on net, worldwide, there really wasn’t any.

How Much of Human Effort Today Is Used to Hack Our Brains to Our Detriment?

Me: Any other things that people are puzzled by, or want to get off their chest

Student: I'm still surprised by the real-wage hockey stick.

Me: Yes. The real wage hockey stick is also terrifying. We know there was a huge amount of technological advance between 8000 BC and 1870—culminating in the telegraph, the steam engine, and steel. Yet it looks like very little of the potential benefits of higher technology filtered down to improve the standard of living of the typical person, as opposed to the upper class.

Today, $17,273 is the average real income per capita level in international current dollars. (We hope it will be $56,000 for the world as a whole by 2075.) That $17,273 compares to typical income of $1,600 per person per year in 1870. And this calculation neglects the fact that we are not only able to produce and make a lot more than people were 150 years ago, but we also have an incredibly greater choice of commodities and types of commodities to make and use. This adds to the potential for human flourishing.

But there is an “on the other hand”.

My scale said this morning I am 244.6 pounds.

If I were a hunter-gatherer, I'd be 160—assuming I had the nutrition I had growing up.

The point at which doctors start lecturing me about how this is seriously healthy is 200.

Yet we have hunter-gatherer brains. Those brains are trained to think: if it's a fat or if it's a sweet, go for it now. High-density energy-nutrition for immediate use, and high-density nutritional storage reserves for potential times of future dearth—those are not common; thsoe are not lying on the ground everywhere, or growing on trees. So if you see such, gobble as much as you can down right now!

And we have a market economy that rewards people and organizations that figure out how to hack our brain by triggering that hunter-gatherer reflex. Hence, 245 pounds rather than 200.

To a large degree, the food industry as it exists today is not friend beyond a point that we reached long ago. How much of what we spend our time doing is similarly the result not of our choosing to live wisely and well, but of people hacking our brains for their financial benefit and not for our well-being?

That is a very big question. That—rather than thinking about production efficiency and distributional equity—may well be what we economists need to be thinking most about today and in the future.

References:

Clark, Gregory. 2005. "The Condition of the Working-Class in England, 1209-2004." Working Paper No. 05-39. University of California, Department of Economics. <https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/31405>.

Diamond, Jared. 1987. "The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race." Discover Magazine. (May): 64-66. <https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-worst-mistake-in-the-history-of-the-human-race>.

Mollick, Ethan. 2023. "The Homework Apocalypse: The Unintended Consequences of AI on Education." One Useful Thing. July 1. https://oneusefulthing.substack.com/p/the-homework-apocalypse.

Steckel, Richard H. 1995. "Stature and the Standard of Living." Journal of Economic Literature 33 (4): 1903-1940. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2729317>.

On the last point - this is why Ozempic and the other GLP-1s are so revolutionary. They correct for our natural inclination towards high calorie overeating. It seems to me like a no-brainer that most people will be using something like that over time.

Agriculture as "mistake". It may have made life rather tough for peasants, but the sendentary lifestyle made possible civilization and all that entailed. The problem today is trying to eliminate the negative effects of civilized life, while retaining the positive ones.