LECTURE NOTES: 5.1. Global Warming

Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth course unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": Global warming & its role in feeding the post-2010 world-economy & -polity & -society...

Rough but edited lecture transcript. Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth course unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": Global warming & its role in feeding the post-2010 world-economy & -polity & -society "polycrisis"...

Global warming is more than an environmental challenge—it's a reshaping force for economic and political systems. As the Neoliberal Order falters, the costs of dealing with global warming will divert resources that could otherwise be used to open new pathways for humanity. Analyzing what the implications of this will be is a very important piece of analyzing our modern global “polycrisis”…

5. After Neoliberalism Comes “Polycrisis”:

Global Warming

Neoliberalism & After

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Economics

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Culture, Politics, & War

The Renewed Fight Over Systems & Orders

5.1. Global Warming

After WWII, the Thirty Glorious Years—the Trente Glorieuses—were amazing. The combination of the Mass-Production Age in the economy and the social-democratic New Deal Order in political-economy provided a template for much of the world that produced stronger economic growth, richer societies, and more equal and harmonious distributions of income and wealth than had ever been seen anywhere, anywhen. Yet this model came to a crash as the 1970s ended. As the Mass-Production Age economy began to be replaced by the Globalized Value-Chain Age economy, so the social-democratic New Deal Order was replaced by what came to be called the “Neoliberal Order”.

Now the wheel has turned again. The Neoliberal Order is now widely seen as having failed. Nobody claims to like it as an approach to organizing society, either economically, politically, or socially. But what is the replacement? Potential alternatives to neoliberalism appear to be even less popular, and more dysfunctional. It is at this point that my friend Jeet Heer likes to quote pre-WWII Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci and analogize his situation with ours. He said: The Old Order is dying. The New Order appears possibly stillborn. Now it is a time of monsters.

How will humanity considered as an anthology intelligence organize itself over the next generation or two, socially, economically, and politically?

The consequences of ongoing global warming are, I believe, biggest difference between what is coming in the years after 2010 and what had come before over the years 1870 to 2010 of the Modern Economic Growth Era. During that period humanity's technological capabilities had doubled every generation, thus generating, repeatedly, enormous technological dividends. These dividends were wealth that could be used to manage the downsides of the constant and repeated episodes of Schumpeterian creative destruction that were inseparable from rapid technological progress and greatly increased human wealth. These dividends were sometimes used to compensate those who found themselves in the destructive bulls-eye of Schumpeterian creative destruction. These dividends were sometimes used to incentivize others to tell and then make potential and actual losers shut up and get back into their place. And so rapid organizational, political, and social change accompanying economic growth was managed—the very buggy human-organization, -distribution, and -cognition software code running on top of our also very buggy and rapidly changing techno-economic human-society hardware was rewritten on the fly, and done so well enough that it did not crash as often or as badly as it might have.

But this avenue of adjustment is unlikely to work nearly as well in our and in future days as it did over 1870 to 2010. Why not? Because of global warming.

5.1.1. Science!

The sun fuses hydrogen to helium in a three-step process. Along with each helium atom comes 27 MeV—million electron-volts—of extra energy from the binding energy of each four-component helium nucleus. That is only 4 x 10^-17 of the kind of calories your iPhone’s dieting program counts. But it adds up. The sun produces 9 x 10^37 newly fused helium nuclei every second. Do the math, and in every second the sun’s energy output is 9.6 x 10^19 times the daily nutritional energy requirements of the entire human race.

Between 360 and 300 million years ago sunlight falling on the earth fed the biosphere which ultimately turned the energy into rock: stored sunlight power in the form of underground coal.

Between 250 and 70 million years ago sunlight falling on the earth fed the biosphere which ultimately turned the energy into liquid and gas: stored sunlight power in the form of underground oil and natural gas reservoirs.

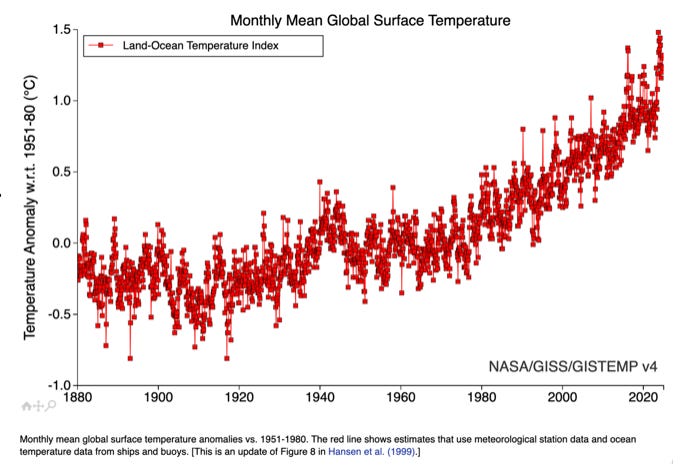

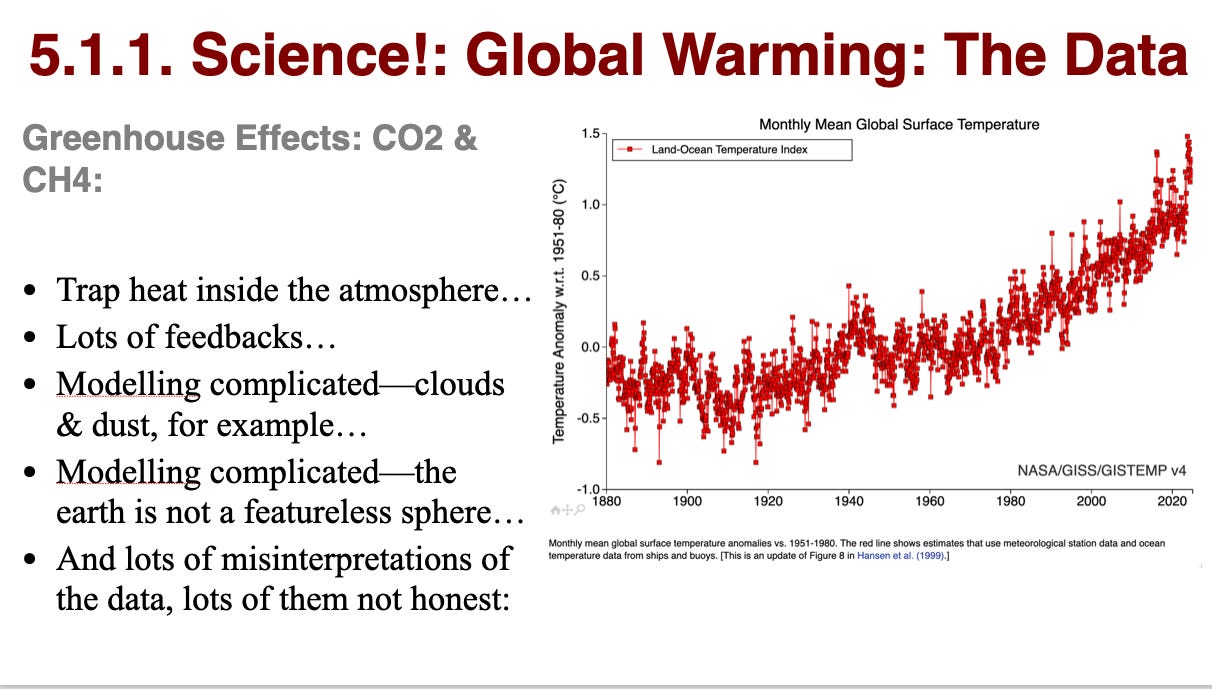

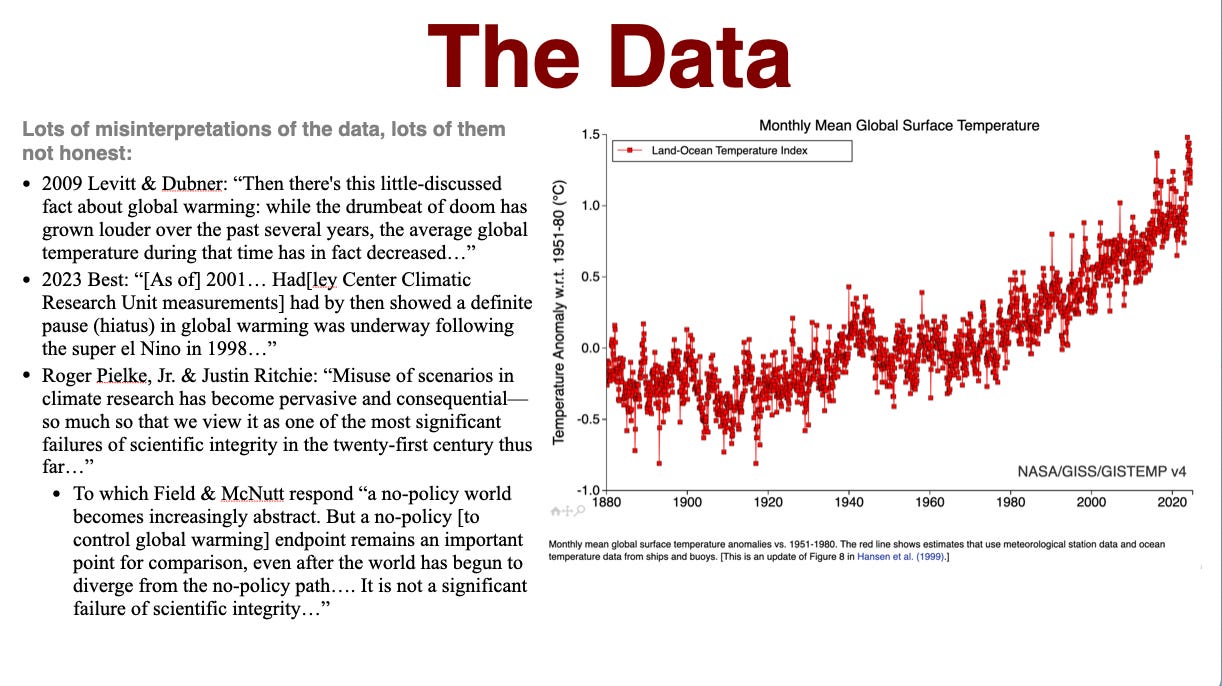

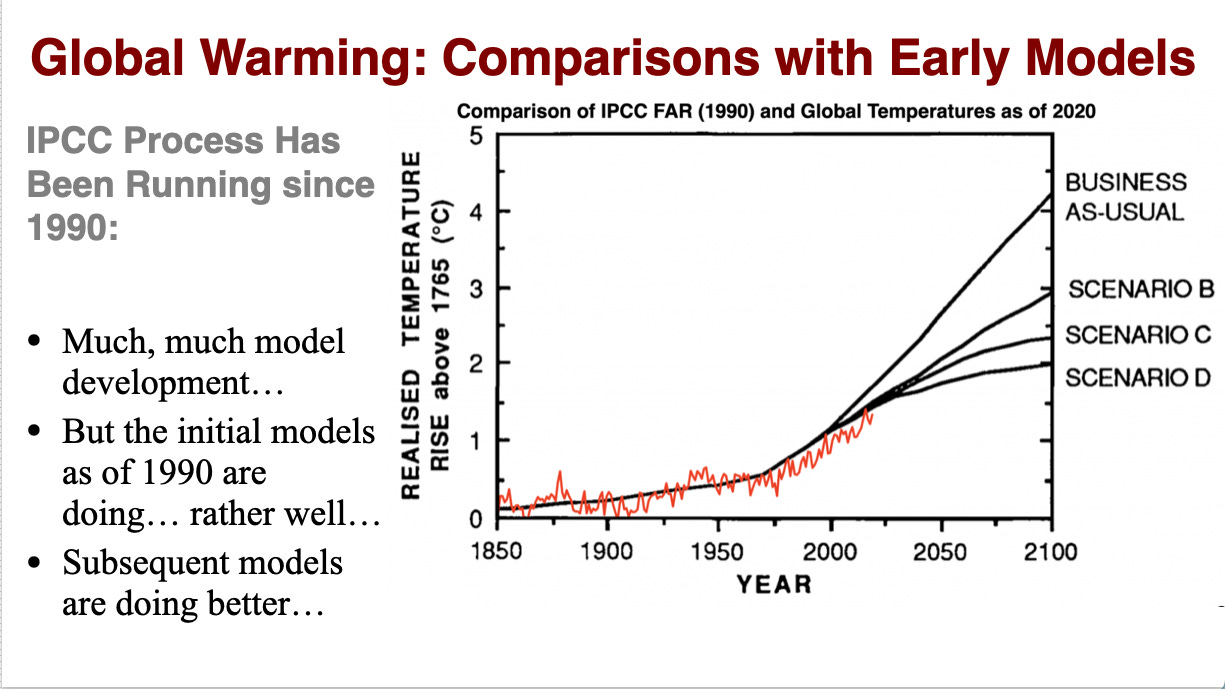

The easy accessibility of these stored solar energy sources, through extraction and combustion, has been tremendously beneficial for human civilization. But carbon dioxide released during combustion floats into the atmosphere traps infrared radiation emitted from the Earth's surface and causes the CO2 molecules to vibrate—heat energy then transferred back down to the Earth, making us warmer. Our using stored sunlight from 360 to 70 million years ago rather than current sunlight to power our civilization is strengthening this “greenhouse effect”. This is a challenge. And it is not hyperbole to say that addressing this challenge is crucial for the future of human civilization.

Here and now, and for the foreseeable future, global warming is driving the climate here in Terra’s northern hemisphere to shift northward at an average rate of 3 miles per year. This poses significant challenges:

The built environment and infrastructure are designed for a different, now-gone climate.

As the climate shifts, the terrestrial footprint of each climate zone we find useful will become smaller in area as it finds itself in higher latitudes.

In addition to the average northward shift, there will also be other changes that will vary from place to place—changes in rainfall, temperature, extreme weather events, droughts, and other things—that threaten very costly disruptions

An abrupt, catastrophic change could occur as global warming causes a sudden shutdown of the Gulf Stream, plunging western Europe into a much colder climate within years.

The melting of permafrost in northern latitudes could release large amounts of CH4 methane, a much more powerful greenhouse gas than CO2 carbon dioxide.

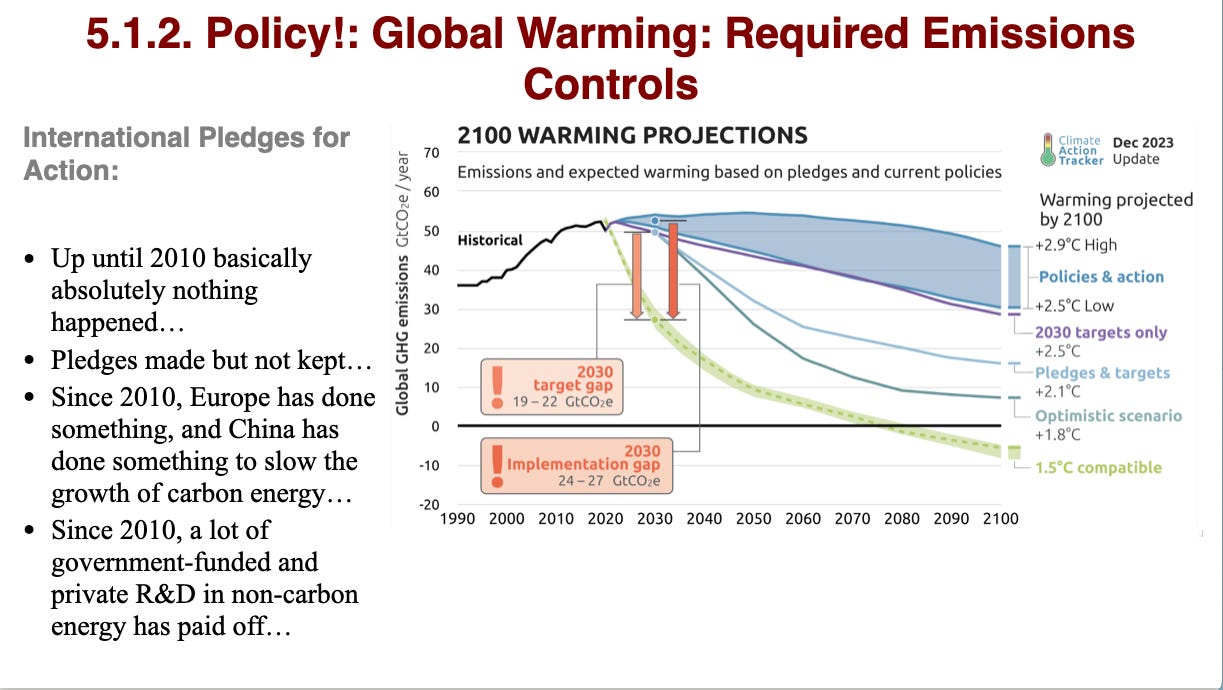

5.1.2. Policy!

Thus the current rapid march of climate zones away from the equator due to human-caused emissions poses serious risks and imposes significant costs.

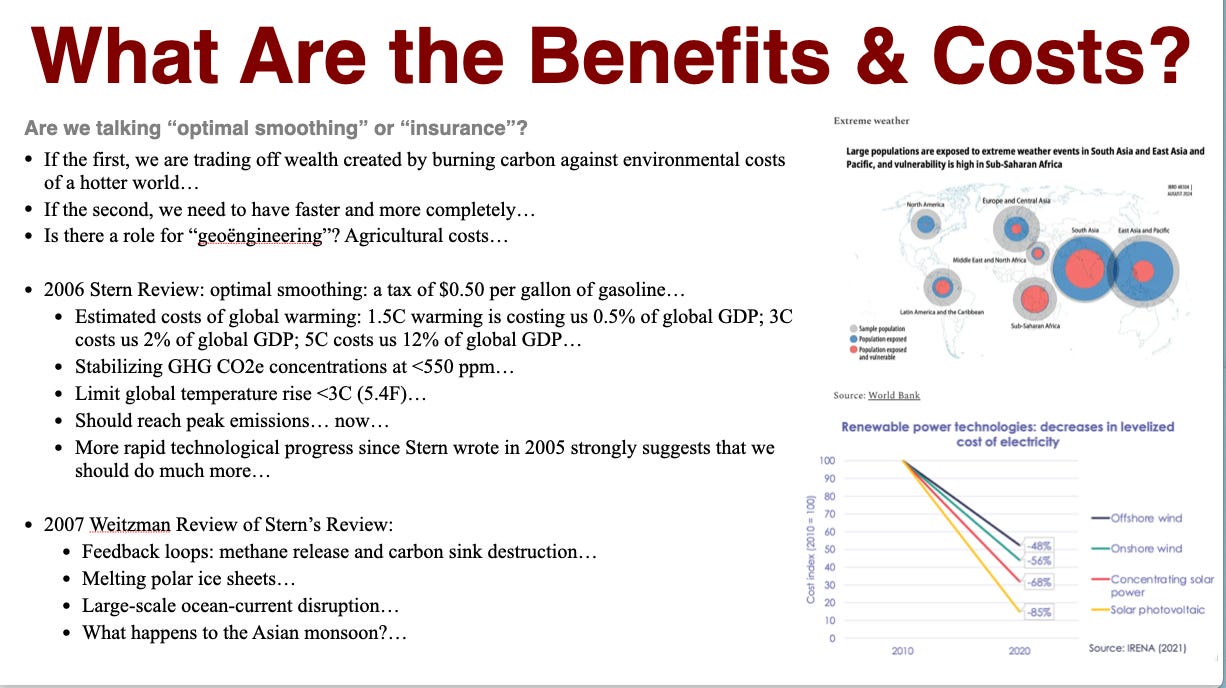

In 2006, the Stern Review led by Nicholas Stern, assessed the economic impacts of climate change. The Review guessed that 2.7°F of global warming would cost the global economy perhaps 0.5% of GDP to address. We are there now. Twice what we have seen so far—a 5.4°F increase—would cost, they guessed, 2% of GDP. And the guess was that a 9°F increase would cost 12% of GDP.

The Stern Review recommended:

stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations at less than 550 parts per million (compared to around 400 million today),

limiting the global temperature rise to less than 5.4°F,

reaching peak carbon emissions globally… now,.

imposing a carbon tax of $40 per ton (about) $0.50 per gallon of gasoline.

Since 2006, technological progress in solar power has been faster than the Stern Review anticipated. This shifts benefit-cost calculations. It entails the conclusion that our optimal actions should be more ambitious.

In 1993, then-Vice President Al Gore pushed the Clinton administration to take action, and the report was that its proposed BTU tax failed to become low by only one single vote in the Senate, as 51 senators (including all Republicans, about 15 of which spent their careers diligently burnishing their reputations as pro-environment), headed by David Boren (D-OK), refused to go along. We have never gotten back there and gotten that close since.

If you find someone who wants to talk to you about global warming, and they will not say that AlGore is a hero who we should have listened to thirty years ago (for it would have been much less costly to start dealing with global warming then than it is starting dealing with it now), then you should dismiss them as at best profoundly unserious, and perhaps deeply malevolent.

5.1.3. Implications!

But this is not a global warming course.

For us, the key question is not about global warming itself, but rather the consequences of global warming for the organization of human society. This includes more than the costs of dealing with global warming. Dealing with global warming will likely eat up much, if not all, of the technological growth dividend that would otherwise be available to help society adapt to ongoing economic disruption and change.

So how then will we grease adjustment to, compensate the losers from, assemble coalitions to manage the ongoing processes of Schumpeterian creative-destruction that will accompany ongoing technological revolution?

If you have ideas, please email them to me.

References:

Hänsel, Martin C., & Ottmar Edenhofer.. 2023. “A New Decade of Research on the Economics of Climate Change”. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 243:5 (October 3), pp. 471–476. <https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jbnst-2023-0070/html>.

Stern, Nicholas, Joseph E. Stiglitz, & Charlotte Taylor. 2022. “The Economics of Immense Risk, Urgent Action and Radical Change: Towards New Approaches to the Economics of Climate Change”. Journal of Economic Methodology 29:3 (February 24), pp. 181–216. <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1350178X.2022.2040740>.

Stern, Nicholas. 2021. “15 Years on from the Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change, Innovation, & Growth”. London: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. <https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Stern_Review_15th_anniversary26_Oct_2021.pdf>.

Stern, Nicholas, & al. 2007. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. <https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/economics-of-climate-change/A1E0BBF2F0ED8E2E4142A9C878052204>.

Weitzman, Martin L. 2007. “A Review of The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change”. Journal of Economic Literature, 45:3 (September), pp. 703–724. <https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.45.3.703>.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

I think you are very kind to the Rich Countries. Yes, they are unwilling to compensate the poor countries for altering their growth paths. But they are also not willing to alter their own growth paths were the adjustment is bumpy. They - we - do not set an inspiring example for poor countries.

The wording of "How _will_ we..." was a bit jarring, although perhaps by design [as Twelve described his strategy in a Doctor Who episode, pretend you have won and explain how you did it]; it's not at all a given from current trends. But it might be an absolutely necessary frame of mind to develop right now.

Doing the backwards-engineering exercise, then:

(1) Escaping the Climate Crisis was costly and required transfers due to built-in mismatches between cost and existing economic capability.

(2) Therefore, the likelihood and effectiveness of a solution was, in hindsight, a function of a larger-than expected global surplus and a renewed willingness for supra-national cooperation and wealth transfers on humanitarian and long-term strategic grounds.

(3) So we were very lucky that our increased investments on human resources [driven in part by population ageing pressures], infrastructure [justified ironically through an international competition framework], and applied science [a side effect of cheap post-bubble computational resources and extremely ambitious unsatisfied expectations], with a particularly large absolute impact in already comparatively productive rich economies, led to such large economic surpluses that it made global adaptation and energy shifts much cheaper in relative terms, while a rapidly increasing quality of life for the bottom 90% [which progressive political forces figured was the only way to buy support from a large majority of the population, and damn the donors; the development of off-platforms political messaging and coordination as the new playbook was key to this] lowered the political friction to do so.

Counterfactuals are always suspect, and no historian claims that the Climate Crisis is what made the Jackpot Prize possible (and most likely it made it harder to achieve) but the consensus is that it did wonders to concentrate a lot of minds.