LECTURE NOTES: 5.3. Post-2010 "Polycrisis": Economics

Rough but edited lecture transcript. Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth Course Unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": The economic aspects of our polycrisis…

Rough but edited lecture transcript. Part of Econ 135: The History of Economic Growth course unit 5. After Neoliberalism Comes "Polycrisis": The economic aspects of our polycrisis…

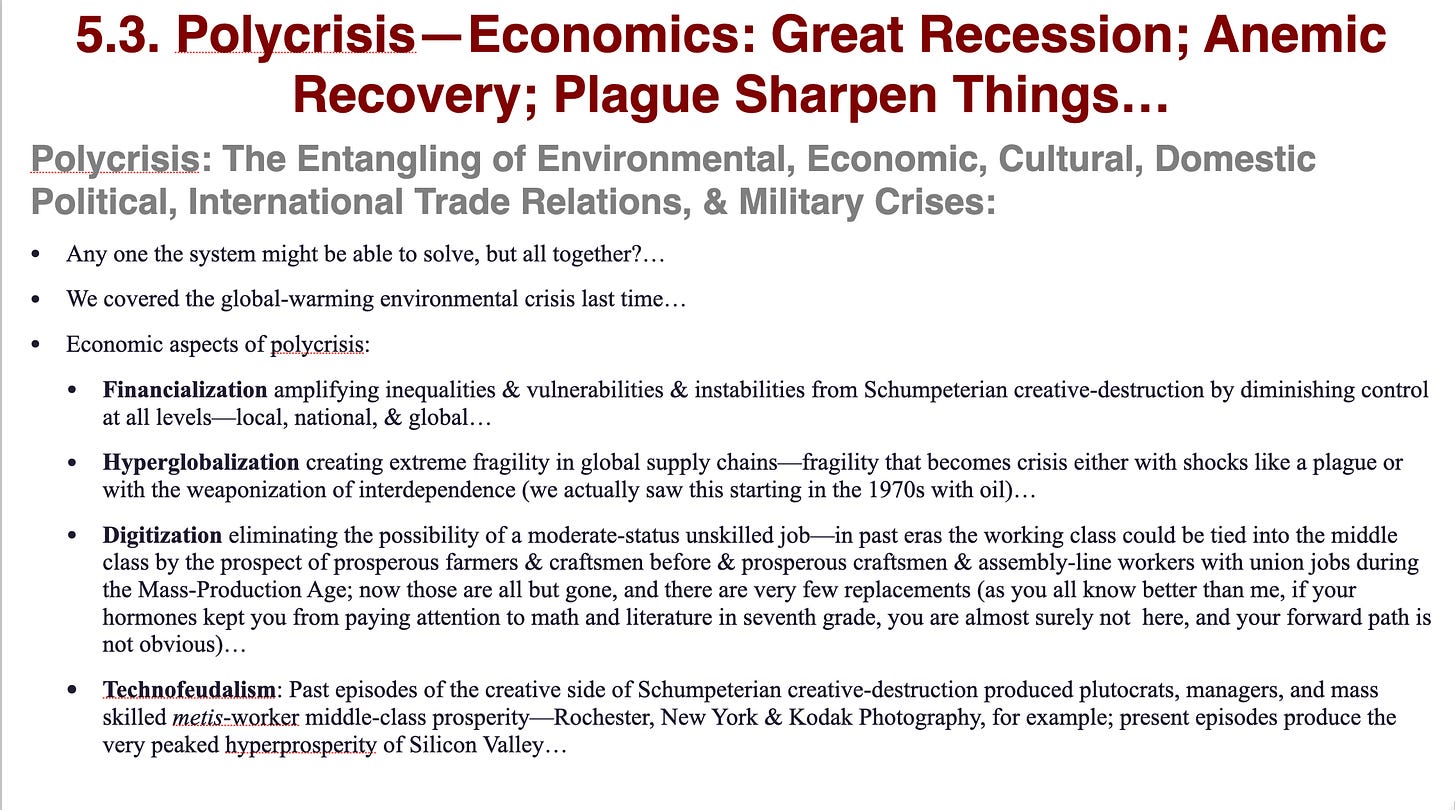

The economic side of “polycrisis” is more than a single business-cycle downturn—it’s the convergence of crises too complex to untangle: excessive financialization, digital disruption, fragile hyperglobalization, and brain-hacking to profit from enserfing our attention all combine in a Gordian Knot of trouble…

5. After Neoliberalism Comes “Polycrisis”:

Global Warming

Neoliberalism & After

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Economics

Post-2010 “Polycrisis”: Culture, Communications, Politics, & War

The Renewed Fight Over Systems & Orders

5.3. Post-2010 "Polycrisis": Economics

As best as I can tell, it was French complexity theorist Edgar Morin who coined the word “polycrisis” back in the 1970s. It describes a situation in which there are multiple crises that seem to be interconnected and mutually reinforcing. The system could surely handle one or two without great disruption. But there are simply too many balls in the air. And so the resolution may be very bad indeed.

Polycrisis is, I think, a very good word.

In 2016, Jean-Claude Juncker, then President of the European Commission, picked up the baton and used the term to describe the multiple challenges facing the Commission of the European Union—the Greek debt crisis, Russia's aggression against Ukraine, Brexit, the Syrian refugee crisis, and more. Since then it is Columbia’s Adam Tooze who has picked up the baton and run far and fast with it as an analytical category useful in tracking what is going on now in the post-2010 world, in what we believe is an interregnum following the collapse of the Neoliberal Order that had seemed to fit with our Globalized Value-Chain mode of production—a societal formation that may itself be on the cusp of being superseded by something that might be an Attention Info-Bio Tech Society, or might not.

Crises encompassing environmental, economic, cultural, domestic political, international trade, and military challenges. Any one of these individual issues the Neoliberal Order almost surely would have found manageable on its own. But all of them? All have arisen because, in one way or another, the Neoliberal Order no longer worked well enough.

Two sections ago we covered the Big Enchilada aspect of our polycrisis: Global Warming. Last section we reviewed what the Neoliberal Order was via a short potted intellectual biography of Milton and Rose Director Friedman; then we went on to note four aspects in which there has been strong rejection of the Neoliberal Order in favor of a demand for: (1) place-based support of communities, (2) explicit economic industrial policy, (3) strongman politics, and (4) rising and mostly imagined fears.

This section we move on and survey four areas of economic polycrisis that successful place-based community-support and industrial-development policies will have to address if they are going to be successful. The four are:

Excessive financialization.

Unstable hyperglobalization.

Digitization’s impact on opportunity and mobility.

What I do not want to call techno-feudalism, but am finding the word sufficiently intriguing and arresting that I put it there, at least here and now.

Excessive Financialization: Increasingly, the economy appears focused on money flows that sit on top of the actual flows of production and purchase of commodities and earning and distribution of income. More and more of economic life is not people trading money for things of use value, but rather people trading money for money in increasingly complex and opaque ways. The focus of attention thus shifts away from making and doing things, and away from the costs and benefits of making things. The focus of attention thus shifts toward what average opinion expects average opinion to be about some financial asset where some portion of the payoff is connected in some way with making and doing things and the costs and benefits thereof—or completely unconnected with making and doing things and the costs and benefits thereof: BitCoin, DogeCoin, GameStop. There are economists from Chicago who will tell you that none of this matters. But I do not think you should believe them. Burning people’s attention in an unproductive and unentertaining way cannot be a good thing.

Moreover, a lot of excessive financialization is a confidence game. There are, after all, two ways to make money in finance: first, to take the side of a transaction in which for some reason the risk is low relative to the reward; second, to find someone who does not understand the risks and induce them to take the side of the transaction in which risk is excessive relative to the reward.

Finance, after all, has four key useful roles in an economy:

First, it allows for economies of scale, enabling large-scale projects that a single person could not undertake alone. Second, it facilitates risk-sharing, allowing individuals to take on riskier but potentially more rewarding ventures by spreading the risk. Third, it enables the transfer of purchasing power across time, allowing those with current income to lend to those who need resources now but will have future income. Fourth, it can help align incentives, by giving stakeholders a vested interest in the success of a venture. Excessive financialization however, brings a growing concern that the financial system is not fulfilling these core functions as effectively as it should. Instead, it is encouraging people to make bets they do not fully understand, leading to regret when the risks materialize. The financial system should be serving the real economy, but there is a perception that it is increasingly serving its own interests at the expense of broader social welfare. And this perception was definitely true in the finance-generated smash-up of the global economy from 2007-2011. Nobody is happy with the world economy’s degree of financialization, except for those who believe they are big winners from it.

Hyperglobalization: The era of the Neoliberal Order was the era of the creation and growth of the Globalized Value-Chain mlde of production. And the development of highly productive global supply chains spanning continents and oceans has led to extreme fragility in these systems. This fragility has resulted in crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Furthermore, governments have increasingly weaponized economic interdependence to pursue their own strategic interests, rather than focusing solely on maximizing global prosperity. This trend is of long standing: we saw it with the oil crises of the 1970s. But it is more of a factor with hyperglobalization. Nobody is satisfied with so much of their prosperity being so fragile.

Digitization has eliminated many relatively high-pay but also relatively low-skill in the sense of lengthy formal training jobs. Those jobs used to allow the working class to align with the middle class. The better-paid members of the working class met the worse-paid members of the middle class on terms of social equality, and could communicate to discover what they shared in common. The better- and worse- paid members of the working class met on terms of occupational commonality, and could communicate to discover what they shared in common. The better- and worse- paid members of the working class met on terms of occupational commonality, and could communicate to discover what they shared in common. Thus there was a potential network of understanding and empathy that could bind society from the worse-paid members of the working class to the best-paid members of the middle class. This was, indeed, a powerful force that held together the societies of the New Deal Order, and created the impetus for the Great French Revolution by forming the belief that the non-royal non-noble non-clerical Third Estate was a very real thing. It also provided confidence that there was opportunity—that the system (possibly excepting the role of the rich) was not totally rigged

In the further-away past, earlier the set of prosperous farmers fortunate in their land and craftsmen fortunate in their apprenticeships made up the working-class component of this alliance of opportunity. In the New Deal Order past, it was craftsmen fortunate in their apprenticeships and assembly-line workers fortunate in their unions who made up this component, with concomitant avenues for upward mobility even for those without extensive education and training and reductions in income inequalities even for those without family advantages. However, these pathways are now much harder to come by. The educational system has become one of the few remaining channels for upward mobility in our global culture. That means that thoses who once struggle academically for whatever reason, even if equally capable, often find it extremely difficult to recover and get back on track. I do not need to tell you that your peers as smart as you are who got distracted by their hormones from paying attention to math and literature in seventh grade are not here with you at Berkeley now.

The disappearance of well-paid yet low-skill jobs has made it increasingly challenging for members of the working class to think that that they can have a measure of success, and thus a stake in society as currently ordered.

There is a fourth very troubling aspect to the economic side of our polycrisis. Call it techno-feudalism. I am finding the word sufficiently intriguing and arresting that I put it there, at least here and now, even though I fear that it may well cloud minds as much as illuminate them.

Does it matter that our current wave of Schumpeterian creative-destruction is destroying occupations and industries in which profit is made by making and selling commodities that directly provide for human utility, and creating experiences in which profit is made by capturing attention and then renting out the eyeballs of those whose attention has been captured to con artists wanting to sell them fake diabetes cures and crypto grifts? (As you see, I have put my thumb on the scale here.) Does it matter that the write-once run-everywhere massive economies of scale of the digital age means that ownership of the intellectual property that gives you control of key financial chokepoints is all, and individual skill and industriousness in actually doing cognitively demanding jobs is worth much less.

The Second Industrial Revolution and its aftermath provide quintessential examples of the classic Schumpeterian paradigm. Consider Rochester, New York, home to Eastman Kodak. The development of photographic technology exemplifies how technological advances transformed consumer goods into accessible commodities. Photography, once a luxury available only to the wealthy, became a ubiquitous medium of personal and professional expression. Kodak’s innovations—from film cameras to the democratization of photography—created a tightly integrated value chain in which technological know-how, capital investment, and skilled labor collaborated to produce tangible goods. These goods were not only profitable but also deeply valued by the public for their utility and cultural significance.

The link between production and consumer satisfaction was direct: people bought cameras and film because these products enriched their lives. The Rochester model created a large middle class of skilled workers who accrued experiential knowledge in manufacturing processes, contributing to a thick network of practical expertise. Second, Finally, the profits earned by firms like Kodak reinforced a virtuous cycle of reinvestment, fostering innovation while raising living standards.

In stark contrast, today’s Silicon Valley operates on a different axis of value creation, offering free services to users in exchange for their engagement, with their eyeballs then sold to advertisers. While these platforms often provide value—through entertainment, social connection, and information dissemination—their profit model does not depend on the direct utility of their services but rather on their capacity to keep users engaged. This economic structure has produced unprecedented wealth for a narrow group of technology founders and investors. Unlike the broad-based prosperity of the industrial era, digital hyperprosperity is highly concentrated.

The most profound shift in the digital economy lies in its product: attention. In earlier episodes of creative destruction, technological innovations produced goods that satisfied clear consumer needs. A camera, for instance, met the demand for preserving memories and creating art. By contrast, platforms monetize consumer engagement itself, often by exploiting cognitive and behavioral vulnerabilities. Attention, rather than physical or experiential goods, has become the commodity.

This transformation has ambiguous implications for human well-being. On one hand, platforms provide value by connecting people, democratizing access to information, and offering moments of entertainment and joy. On the other hand, the mechanisms of attention capture—endless scrolling, personalized algorithms, and behavioral nudges—can foster addiction, reduce productivity, and erode mental health. After spending hours on a social media platform, a user may feel entertained or informed—or they may feel drained, distracted, and regretful. The link between the profit-flow of these companies and consumer utility is more tenuous.

Are we creating an economy in which the most successful firms thrive by monetizing distraction rather than creating products that improve human lives?

The idea of eudaimonia—flourishing or living a life of deep fulfillment—may provide a useful lens here. Are our digital platforms working for us? Or our we working for them?

Even if it is true that we are getting very little or negative utility out of our digital lives while our techno-princes amass galaxy-scale fortunes from the money that the con artists pay them for harvesting our attention and making us their marks, techno-feudalism is hyperbole. But it does capture the ideas of the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few, with most exploited and without true autonomy, and some arranging things to benefit from the techno-princes’ largesse.

Excessive financialization, hyperglobalization, digitization, and techno-feudalism on the one hand, demand for place-based and explicit industrial-development policies, strongmen, and fear on the other—even on the economic side alone, our current polycrisis is a true Gordian Knot.

References:

Tooze, Adam. 2023. “This Is Why 'Polycrisis' Is a Useful Way of Looking at the World Right Now”. World Economic Forum. May 7. <https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/03/polycrisis-adam-tooze-historian-explains/>.

Polycrises are historically civilization ending (or so my historian wife reminds me when I get too techno-optrimistic about the future). I don't expect our global civilization to collapse, but it does sufggest a major realignment of the world order, and not in a good way. What might be a good path is to take the idea of reducing inequality seriously, while also taking the majority views serious about healthcare, reproductive health, and most important, global heating and actaully doing something to achieve those goals. I would hate to think we need a dictator to do this, (and the one the country selected is 180 degrees out of step with the majority), but US democracy as currently structured seems unable to do the job. As Lessig has long stated, money in politics is a real underlying problem and needs to be eliminated, rather than, as now, liberated to do as much damage as it demonstrably does.

Is it really clear that the era of neoliberalism is over? Yes, there are higher tariffs and an attempt to bring manufacturing back from overseas. But so far this seems more like a difference in degree than anything new. Neoliberalism may turn out to be like "late capitalism," the idea that capitalism is on its last legs. Note that this idea is over 100 year old. And yet capitalism is still around.