HOISTED FROM ÞE ARCHIVES: Lessons from þe New Deal (2009-03-31)

My testimony before Sen. Sherrod Brown's subcommittee...

Earlier today Eric Rauchway @rauchway wrote that people should take a look at my 2009-03-31 testimony that Sen Sherrod Brown (D-OH) invited me to give:

He is right: my 2009-03-31 testimony is damned good!

LESSONS FROM THE NEW DEAL: HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ECONOMIC POLICY OF THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS :: UNITED STATES SENATE :: ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS :: FIRST SESSION

ON:

WHAT LESSONS CAN CONGRESS LEARN FROM THE NEW DEAL THAT CAN HELP DRIVE OUR ECONOMY TODAY?

MARCH 31, 2009

Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

(Available at: <http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/senate/senate05sh.html>) U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 53–161 PDF WASHINGTON : 2009…

WRITTEN PREPARED STATEMENT OF J. BRADFORD DELONG

PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY

MARCH 31, 2009

Chairman Brown, Senator DeMint, other Members of the Committee: It is always an honor to be invited here to participate in a small part in our self-rule via representative government here in the oldest and strongest and most successful large Republic in the world. We today face an economic crisis, and a crisis that has few parallels. Thus we are driven back to historical analogies. It can be said that eco- nomic theory is always crystallized history, is always us drawing on lessons from the past. But usually enough of the past has gone into making the theory that we are happy with the crystallized version. For this crisis, however, there is only one even close past parallel: the Great Depression and the New Deal. And so this time it is, I think, best to drink the history raw.

Drawing lessons from the New Deal for the Great Depression requires, first, understanding what the New Deal was. Franklin Delano Roosevelt took everything that was on the kitchen shelf and threw it into the pot on March 4, 1933, and then began stirring—fishing things out that seemed nasty (and watching the Supreme Court fish a bunch of stuff out too), adding spices, adding new ingredients as they came along, all the while watching the thing cook and trying to turn it into some- thing tasty. Try everything—and then reinforce and extend the things that seem to be working well. Ellis Hawley’s The New Deal and the Problem of Monopoly remains the best account of this process. As Franklin Delano Roosevelt said on May 23, 1932:

The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions who are in want will not stand idly by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.

It is only after the fact that we can say what the New Deal was. And it is only after the fact that we can try to assess the parts of it that were worthwhile and the parts of it that were not. In the middle of it nobody was really sure what was going on.

I believe that in retrospect the New Deal is best divided into four components:

(a) income redistribution to level the gross inequalities and inequities that had grown so large in the Gilded Age;

(b) social insurance programs that diminished the risks that Americans would find themselves destitute and totally dependent on spotty and inadequate individual acts of charity;

(c) structural reforms of the economy; and

(d) what we now call macroeconomic policy—the government’s taking responsibility for and acting as the balance wheel on the aggregate flow of spending and thus production and employment.

Of these I believe (a) and (b), income redistribution and social insurance, surely made post-New Deal America a much better place but had little if any impact on recovery from the Great Depression. I also believe that (c), structural reforms of the economy, had little or no net impact on recovery as well. Some of the structural reforms appear to me to have been well thought- out—REA, NLRA, and Thurman Arnold’s drives for enforcement of the antitrust laws come to mind. Others appear to me to have been neutral or worse—the NIRA and the PUHCA come to mind.

Indeed, last month I reread John Maynard Keynes’s two substantial letters to Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s and found that my conclusions were the same as those of Keynes, who protested:

[A] great deal of what is alleged against the wickedness of [utility] holding companies is surely wide of the mark. . . . No one has suggested a proce- dure by which the eggs can be unscrambled. Why not . . . leave the exist- ing organizations undisturbed, so long as the voting power is so rearranged . . . that it cannot be controlled by . . . a minority . . . ? . . . Finally, the railroads. . . . Whether hereafter they are publicly owned or remain in pri- vate hands, it is a matter of national importance that they should be made solvent. Nationalise them if the time is ripe. If not, take pity . . . And here too let the dead bury their dead.1

and:

You are engaged on a double task, Recovery and Reform . . . For the first, speed and quick results are essential. The second may be urgent . . . but haste will be injurious, and wisdom of long-range purpose is more necessary than immediate achievement . . . [T]he order of urgency between measures of Recovery and measures of Reform has [not] been duly observed . . . In particular, I cannot detect any material aid to recovery in NIRA . . . The Act is on the Statute Book; a considerable amount has been done towards implementing it; but it might be better for the present to allow experience to accumulate . . . NIRA, which is essentially Reform and probably im- pedes Recovery, has been put across too hastily, in the false guise of being part of the technique of Recovery.2

This leaves the fourth aspect of the New Deal—the recovery-generating aspect— macroeconomic policy, which I also divide into four components:

(a) conventional monetary expansion,

(b) quantitative easing,

(c) banking-sector recapitalization and regulation, and

(d) fiscal policy expansion.

How effective was it? Let me pause to note that if this were 6 years ago in 2003 or 8 years ago in 2001 we would all be taking it for granted that the expansionary monetary and fiscal policies of the types tried during the New Deal were effective. Indeed, had Senator McCain won the presidential election last November the members of this and the previous panel would include one or more senior McCain economic advisors like Douglas Holtz Eakin, Kevin Hassett, or Mark Zandi—all of whom would be arguing that New Deal-like monetary and fiscal stimulus programs were effective as part of the process of arguing for the McCain fiscal stimulus program or the McCain banking recapitalization program that would, had recent history taken another branch, now be moving through the Congress.

Back at the start of the Great Depression none of the major industrial powers of the world pursued expansionary macroeconomic policies. Instead, they held that that government is best which governs least as far as economic policy was concerned and bound themselves with the golden fetters of the classical gold standard. A balanced budget was necessary to maintain confidence that a country would maintain its gold parity—hence no fiscal policy expansion. Under the gold standard the do- mestic money supply was determined by the ebb and flow of gold reserves—hence no, or rather little, conventional monetary policy or quantitative easing. And under the gold standard countries except for Great Britain had very limited powers to sup- port or recapitalize their own banks: when Austria tried in 1931 it found itself faced with an immediate choice of abandoning its banking policy or abandoning the gold standard.

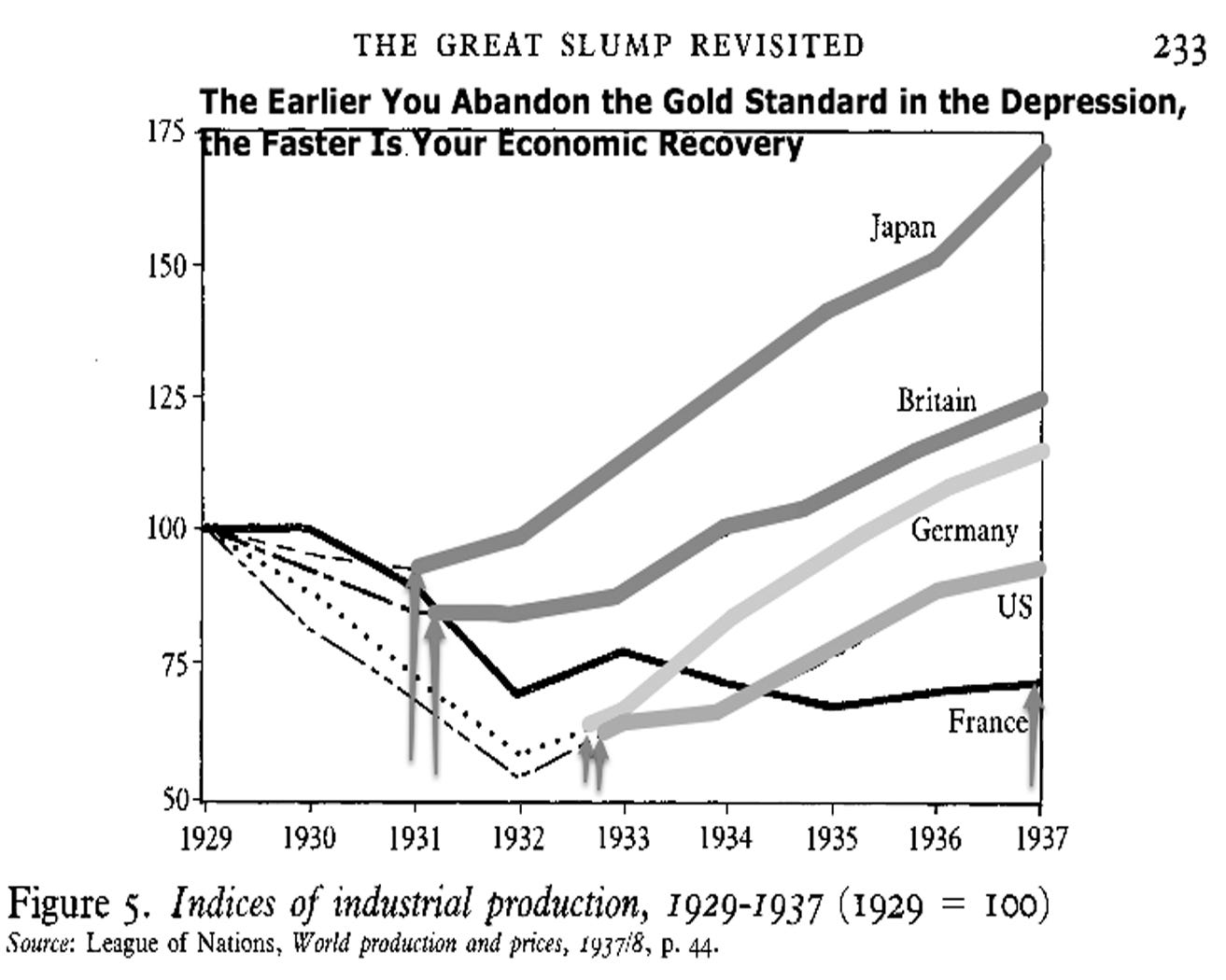

So a New Deal was simply not possible as long as countries remained on the gold standard during the Great Depression—only after the golden fetters were cast off could the government even try to use its monetary, fiscal, and banking policy tools to promote recovery. This constraint gives us as clear evidence as we want that the New Deal—or rather New Deals, for each major industrial country during the Great Depression had its own—mattered for recovery. We know when each of the five major industrial countries cast off the gold standard fetters and began its New Deal. We know how quickly each of them recovered from the Great Depression.

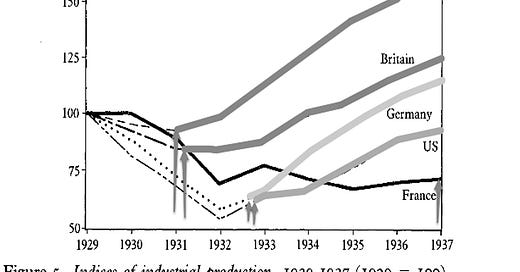

There is a strong rank correlation between how early a country abandoned gold and began its New Deal on the one hand and how rapid and complete its recovery was on the other, as this chart that I have reproduced from Eichengreen (1992) and then added to shows.3 Statisticians will tell you that if you thought before looking at the evidence summarized in this rank correlation that there was only a 50–50 chance that New Deals mattered for recovery, then after looking at this evidence you should rationally be 95.2 percent sure that New Deals mattered.

We economists are pretty sure that all four components of macroeconomic policy helped. It is very hard to write down a model of the economy in which some tools work and others do not. All four operate through boosting spending—conventional monetary policy and banking-recapitalization policy by lowering the interest rates that businesses seeking funding to spend on expanding capacity are charged, quan- titative easing by putting cash in people’s pockets that burns a hole through them if not spent, fiscal policy expansion by having the government spend directly. Any model of the economy in which increases in spending boost not just prices but pro- duction and employment will see all four be effective. Any model of the economy in which increases in spending just cause inflation but don’t boost employment and output will see none of them be effective—but we already know that the odds of such being the right model are only 4.8 percent at best.

Which of the four components of macroeconomic policy helped the most in the New Deals’ aiding of recovery? That is a much more difficult question. The Depres- sion itself provides little evidence of the balance of power between monetary, bank- ing, and fiscal policy.

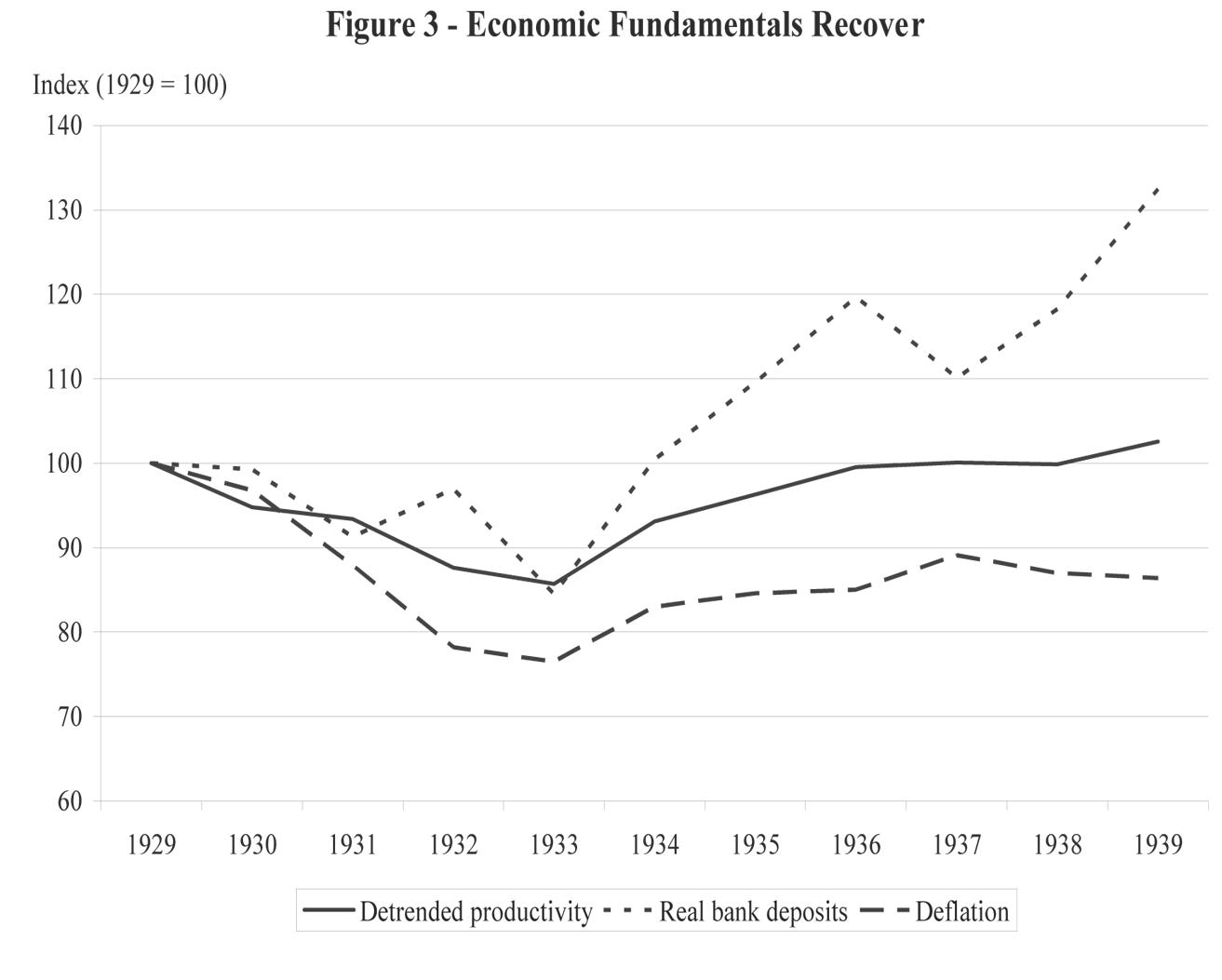

Christina Romer argues powerfully that quantitative easing was decisive—that ‘‘nearly all the observed recovery of the U.S. economy [starting in 1933] prior to [the beginning of World War II] in 1942 was due to monetary expansion,’4’ and this monetary expansion was entirely quantitative easing because conventional interest-rate open-market policy had been tapped out before the recovery began. 4 One thing that students of the Great Depression do agree on is that it is next to impossible to evaluate how powerful fiscal policy expansion was in the Great Depression because it simply was not tried on a sufficiently large scale. As Eichengreen (1992) wrote a decade and a half ago:

In the U.S., the most important fiscal change of the period, in 1932, was a tax increase, not a reduction, observed budget deficits were small. Cyclically-corrected deficits were smaller still. This is the conclusion of Brown . . . for the U.S.; Middleton . . . for Britain; and Jonung . . . for Sweden . . . In contrast, in countries like the U.S. (and to a lesser extent the U.K.) the [monetary] expansion of currency and bank deposits was enor- mous. The one significant interruption to monetary expansion in the U.S., in 1937, revealingly coincided with the one significant interruption to eco- nomic recovery . . . Even in Sweden, renowned for having developed Keynesian fiscal policy before Keynes, monetary policy did most of the work.

For evidence of the ability of fiscal policy to boost employment and production— if used on a sufficiently larges scale—we have to wait until World War II. Monetary policy contraction, banking-sector collapse, and the transformation of irrational exuberance into unwarranted pessimism carried the U.S. unemployment rate from 2.9 percent up to 22.9 percent from 1929 to 1932. Monetary expansion and banking re- form then drove the unemployment rate down to 9.5 percent by the start of large- scale mobilization in 1940. And wartime government expenditure and deficits drove the unemployment rate down to 1.2 percent by 1944.

Thus my belief is that the principal lessons of the Great Depression and the World War II eras for economic recovery are twofold:

The government should not sit on its hands. The French government sat on its hands, relying on its commitment to the gold standard and the equilibrium- restoring forces of the market to handle the Depression. As of 1937—eight years after the previous business-cycle peak—it was still waiting, like Japan in the 1990s, for the self-correcting forces of the marketplace to come to its res- cue.

All four macroeconomic policy tools are likely to have some power. A prudent policy will not rely on any of conventional monetary policy or quantitative eas- ing or fiscal expansion or banking policy alone, but will instead combine all four—and, like Roosevelt, seek to reinforce success.

The New Deal: Lessons for Today—Questions and Answers

Q: How much has Ben Bernanke’s reputation suffered as a result of his failure to stop the recession?

A: I don’t think Bernanke’s reputation as an economist has suffered at all. I think it is stronger than ever. Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History of the United States argued that the Federal Reserve all by itself could have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks—but did not. This thesis of The Monetary History of the United States has taken a profound hit over the last 2 years, for Ben Bernanke has—via open market operations and quantitative easing—done exactly what Friedman–Schwartz recommended and claimed would have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks. Yet we all now think that that is not enough—that we need banking policy and fiscal policy as well. And this is an intellectual loss for Friedman– Schwartz. But it is an intellectual victory for Bernanke–Keynes, who argued that all the conventional interest rate and quantitative easing monetary policy in the world might not be enough if the capitalization of the banking sector vanished and the credit channel got itself well and truly wedged. This is where we seem to be.

Paul Krugman wrote:

Has anyone else noticed that the current crisis sheds light on one of the great controversies of economic history? A central theme of Keynes’s Gen- eral Theory was the impotence of monetary policy in depression-type condi- tions. But Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in their magisterial mone- tary history of the United States, claimed that the Fed could have pre- vented the Great Depression . . . if the Fed had done more—if it had ex- panded the monetary base faster and done more to rescue banks in trouble. So here we are, facing a new crisis reminiscent of the1930s. And this time the Fed has been spectacularly aggressive about expanding the monetary base: And guess what—it doesn’t seem to be working well enough.

The Federal Reserve in the Great Depression

Q: Why do we need to do all this fiscal policy and banking policy stuff? Didn’t Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz prove that the Federal Reserve caused the Great Depression by inept and destructive policies?

A: I think you have to be careful here. Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History of the United States argued not that the Federal Reserve caused the Great Depression but that the Federal Reserve all by itself could have stopped the Great Depression—but did not.

This thesis of The Monetary History of the United States has taken a profound hit over the last 2 years, for Ben Bernanke has—via open market operations and quantitative easing—done exactly what Friedman–Schwartz recommended and claimed would have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks. Yet we all now think that that is not enough—that we need banking policy and fiscal policy as well.

Government Workers and Unemployment

Q: Amity Shlaes writes that the New Deal did not diminish unemployment much—that unemployment was 25 percent in 1933 and still 19 percent in 1938. Doesn’t this prove that the New Deal was ineffective?

A: Amity Shlaes is using the Lebergott unemployment series—and Christie Romer wrote the book, literally—it’s her dissertation—on what is wrong with the Lebergott series. The Romer series or the Weir series paints a very different picture: a fall in unemployment from 23 percent in 1932 to 9 percent in 1937, a jump back up to 12 percent in the recession of 1938, and then a fall to 11 percent in 1939.

As Bush Administration Commerce Undersecretary Michael Darby pointed out, the big difference between the series that matters here concerns their treatment of government relief workers: is someone working for the WPA or the CCC employed or unemployed? From the perspective of ‘‘how good a job is the private sector doing at generating jobs,’’ there is a case for counting them as unemployed. But if the question is ‘‘did the New Deal help?’’ then there is absolutely no case at all for using the Lebergott series because WPA and CCC workers had jobs and were very glad to have them. Shlaes has, I think, simply not read the footnotes to the edition of Historical Statistics of the United States that she got her numbers out of.

Herbert Hoover

Q: Wasn’t the Great Depression really the fault of that dangerous leftist Herbert Hoover with all of his interventionist meddlings in the economy?

A: Herbert Hoover is an interesting case. He wanted to meddle—he wanted to be an activist president—but his Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon persuaded him not too. Mellon persuaded him to raise taxes during the Great Depression to assure investors that the U.S. would stay on the gold standard and not fund government spending by printing money. Mellon persuaded him to avoid expansionary monetary policy of any kind. Herbert Hoover did call business leaders into the White House for conferences, and did plead with them not to fire workers or cut wages too much, but I have never been able to find any sign that this had an effect—no sign that industrialists called to the White House for meetings changed their business prac- tices in any way. Herbert Hoover did start the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, but funded it at a very low level. Because of Mellon’s blocking position in the admin- istration, the New Deal could not get under way until 1933.

Afterwards, Herbert Hoover was very angry at himself for taking Mellon’s counsel and at Mellon for giving it. Until George W. Bush unleashed his White House staff to slime Paul O’Neill, Herbert Hoover held the record for the most vicious attack by a President on his own Secretary of the Treasury, writing in his memoirs that he was very sorry about the influence exercised by:

[T]he ‘‘leave it alone liquidationists’’ headed by [my] Secretary of the Treas- ury Mellon, who felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: ‘‘Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate.’’ He insisted that, when the people get an inflation brainstorm, the only way to get it out of their blood is to let it collapse. He held that even a panic was not altogether a bad thing. He said: ‘‘It will purge the rottenness out of the sys- tem. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people’’

Fiscal Policy

Q: Many economists say that fiscal policy does not work—that Roosevelt’s deficit spending did not pull the U.S. out of the Great Depression.

A: They are wrong. Roosevelt’s deficit spending did pull the U.S. out of the Great Depression—but it did not do so until World War II, which was when the deficit spending really took place. The deficits of the New Deal era seemed large and shocking to people at the time, but they were small relative to the scale of the whole economy. Peak unemployment in the Great Depression hit 23 percent. To reduce that to 5 percent would have required deficits as large as 9 percent of GDP or more—which we did not have until World War II. Thus it is not surprising that unemployment stayed above 10 percent until the eve of World War II.

The NIRA and NLRA as Neutral

Q: Did structural reforms like the NIRA and the NLRA help recovery?

A: I think there is somewhat more than a grain of truth in the claim that much of the New Deal, especially its structural interventions in the economy, was ineffec- tive and neutral—as far as its impact on recovery from the Great Depression was concerned. And there is a grain of truth in the claim that some of it was counter- productive.

John Maynard Keynes told Roosevelt so in a letter of February 1, 1938. And Keynes went on to argue that the reason the U.S. recovery had stalled out in 1937– 1938 was that Roosevelt’s policies were not Keynesian enough—that ‘‘the present [renewed] slump could have been predicted with absolute certainty’’ by anybody knowing the year before how Roosevelt was going to try to reduce deficit spending and tighten money. But that the New Deal was not Keynesian enough does not mean that we should be even less Keynesian now than we are being. And the argument that Milton Friedman and John Maynard Keynes were both wrong when they blamed the renewed 1938 downturn on contractionary macroeconomic policies—well that is an argument that Ohanian is a very brave man indeed to make.

The NIRA and the NLRA as Harmful

Q: Wasn’t the New Deal harmful to recovery because it introduced blockages into labor and product markets?

A: I don’t think anyone has argued that the NIRA and the NLRA boosted aggre- gate demand and put more people to work. That said—output and employment were growing very rapidly in the period when the NIRA was in effect, so if it was doing harm it seems likely that other aspects of the New Deal—abandoning the gold standard, giving up the target of achieving immediate budget balance, quantitative easing—were doing good. The years during which the NRA was in effect saw the unemployment rate go from 22.9 percent down to14.4 percent.

And Milton Friedman was certain that the recession of 1937–38 was not due to the NLRA and to greater union power but rather to a bad mistake of monetary policy in raising reserve requirements. In early 1937 the Federal Reserve doubled required reserves out of fear of future inflation, and the economy fell off a cliff as a result. I don’t know anybody who hated strong unions more than Milton Friedman— yet he did not blame them for the recession of 1937–38.

To step back, the ‘‘impediments to market competition’’ that Ohanian blames for the persistence of the Great Depression were still around and were stronger than ever in the late 1940s and 1950s. If they did not produce high structural unemployment then, what reason is there to think that they produced high structural unemployment in the U.S. in the 1930s?

The NIRA: More

Q: What is your view of Roosevelt’s signature initiative of his first year in office—the National Recovery Administration, the National Industrial Recovery Act?

A: I believe that my view of the NRA is the same as John Maynard Keynes’s view: that it was a mistake. When I read John Maynard Keynes’s open letter to Franklin Delano Roosevelt of December 31, 1933, I can hear Keynes desperately trying not to be impolite while discouraging Roosevelt from any further policy moves along the lines of the NRA. Keynes wrote:

I cannot detect any material aid to recovery in NIRA . . . The Act is on the Statute Book; a considerable amount has been done towards imple- menting it; but it might be better for the present to allow experience to ac- cumulate . . . NIRA, which is essentially Reform and probably impedes Re- covery, has been put across too hastily, in the false guise of being part of the technique of Recovery.

I think the NIRA could have done significant damage to the economy had it not been negated by the Supreme Court. As things were, however, I don’t think it had a material effect. Output was too depressed and demand too low for the NRA codes to have materially depressed it further during the short time it was in operation.

The NLRA: More

Q: Some economists blame slow recovery from the Great Depression in the United States on the NLRA and the consequent rise to power of American labor unions— that they pushed up wages, and so priced workers out of the labor market.

A: The NLRA came too late to be blamed for the Great Depression. The most you can do is blame it for the 1937–38 recession. If you are going to blame strong unions for high unemployment in the late 1930s, you then have to come up with a reason for why even stronger unions in the 1950s did not produce high unemployment. And you have to explain why Milton Friedman disagrees withyou—why Milton Friedman does not see union power but rather the contraction of the money stock as the cause of the rise of unemployment in 1937–38.

Slow Recovery From The Depression

Q: Shouldn’t the economy have recovered completely from the Great Depression by 1936? Doesn’t the fact that the Great Depression continued through the 1930s suggest that the New Deal was harmful?

A: The same models that tell Professor Ohanian, starting in 1932, that the Great Depression should have been over by 1936 also tell him, if you start them in 1928, that the Great Depression did not happen at all.

The pattern across industrial economies is: the later you start your New Deal, the worse you do. That is a striking pattern.

Unemployment Lower Before Roosevelt

Q: If the New Deal was such a success why was unemployment lower before Roosevelt, as Professor Ohanian says?

A: This is true only for a very peculiar definition of ‘‘before Roosevelt’’—a normal person would think that ‘‘before Roosevelt’’ meant 1932 or perhaps the winter of 1932–33. But Cole and Ohanian mean, instead, an average of 1930–1932. Nineteen twenty-nine was a boom year of extremely high unemployment. Nineteen-thirty was an average year. Nineteen-thirty-one was a bad year. But it was only after the fi- nancial crises of late 1931, say Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, that the cratering of the system of financial intermediation and the sudden rise in the reserve-deposit and currency-deposit ratios turned the downturn into the Great Depression. To compare the New Deal Era to the average of 1930–1932 is not just to move the goalpost—it is to pick up the goalposts and run as fast as you can out of the stadium.

Weekly Hours at the End of the 1930s

Q: Total hours worked per adult in 1939 remained about 21 percent below their 1929 level—doesn’t that prove that the New Deal was a failure?

A: Cole and Ohanian work very hard to try to convince their readers that things got worse after Roosevelt took office. But, as they know well, they didn’t: things got better—they just did not get enough better to get employment back to normal until the huge burst of federal deficit spending that was World War II.

Break their claim into two parts. The first part: unemployment was 22.9 percent in 1932 and down to 11.3 percent in 1939—yes, that tells us that recovery was incomplete.

The second part: hours of work per employed person were 13 percent lower in 1939 than in 1929. Cole and Ohanian assume that all of this decline in hours of work per week per employed person is due to deficient demand rather than to a much-desired increase in leisure. I don’t think that is right. In 1949 hours worked per adult were 18 percent and in 1959, 17 percent below their 1929 level. But does that mean that the economy was even more depressed in the 1950s than it was in 1939? No. You don’t want to maintain that the interwar decline in hours worked tells us about cycle and not trend. Is there anyone who will say that the decline in hours worked from 1914 to 1952 tells us that the economy was performing much worse along a business-cycle dimension in 1952 than it was in 1914? No. The 1914–1950 period saw the last sharp decline in the American workweek—a decline that does not mean that the economy was depressed and performing poorly in 1959 or 1949 (or 1939) relative to 1914 or 1929, but instead that Americans had decided to take a substantial part of their increased technological wealth and use it to buy in- creased leisure.

Private Investment

Q: Didn’t Roosevelt’s New Deal Policies destroy business confidence and deepen the Great Depression?

A: The most aggressive claim to this effect that I have seen comes from Professor Bryan Caplan of George Mason, who wrote that: ‘‘[Robert] Mugabe has made people afraid to invest in Zimbabwe. Why should [Brad] doubt that—on a smaller scale, of course—Roosevelt made people afraid to invest in the U.S.?’’

The answer is: no, Franklin Delano Roosevelt bears no resemblance to Robert Mugabe.

And the answer is: no, Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s policies did not depress private investment by making businessmen more scared to invest in America; when FDR took office, businessmen were already totally scared to invest in America—net investment was well below zero, and could hardly drop any further.

Public confidence in markets reached a nadir in 1933, when half the banks in the country had closed, when Wall Street was out of business, when the Dow stood at its appalling lows. Before the new deal there was no securities industry, no banking industry, no mortgage industry, no capital formation or lending of any kind. Forty percent of home mortgages were in default. It was only with the passage of New Deal efforts—the SEC, the FDIC, the FSLIC—that the mechanisms of private cap- ital began to kick back into gear. Don’t take it from me. Take it from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, who wrote in his essays on the Great Depression that: ‘‘only with the New Deal’s rehabilitation of the financial system in 1933–35 did the economy begin its slow emergence from the Great Depression.’’

ORAL DELIVERED STATEMENT OF J. BRADFORD DELONG, PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY

Mr. DELONG. Thank you, Chairman Brown, Senator Merkley.

Drawing lessons from the New Deal requires, first, understanding what the New Deal was. Franklin Delano Roosevelt took everything that was on the kitchen shelf and threw it into the pot on March 4, 1933, and then began stirring, fishing things out that seemed not to be so tasty and having the Supreme Court fish a good deal of it out as well; adding spices, adding new ingredients, all the while watching the thing cook.

Now, the aspect of the New Deal we focus on today is the expan- sionary monetary policy aspect. The conventional interest rate re- ductions, the quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve in the late 1930s, banking sector nationalization and recapitalization, and fiscal policy expansion—how effective were these?

Well, I think there is a broad, near-consensus that the expansionary macroeconomic policies of the New Deal era were effective. Had Senator McCain won the Presidential election last November, the first panel here would not have had Christina Romer. She would be back at Berkeley, and I would not be having to teach her course this semester. Instead, it would have someone like Douglas Holtz-Eakin or Kevin Hassett or Mark Zandi, one of John McCain’s senior economic advisers, all of whom would be arguing that New Deal-like monetary and fiscal stimulus programs were effective as part of arguing for the McCain fiscal stimulus program that would in all likelihood—or the McCain banking recapitalization program that would in all likelihood be proceeding through the Congress.

Now, back at the start of the Great Depression, none of the major industrial powers of the world pursued these expansionary macroeconomic policies. They held instead that the government is best which governs least as far as interventionist policy is con- cerned, and they bound themselves with the golden fetters of the gold standard. Only when these were broken could a New Deal begin in any of the major industrial countries, and we know when each of the five major industrial countries of the world back during the Depression case off its golden fetters and began its New Deal, we know also how quickly each of them recovered from the Great Depression. That is the chart up there on your right.

There is a very strong correlation between how early a country abandoned gold and began its own individual New Deal on the one hand and how rapid and complete its recovery was on the other, as this chart I have reproduced from Barry Eichengreen’s 1992 ar- ticle and then scribbled on myself shows. Those economies that abandoned the gold standard and started expansionary monetary and, to a lesser extent, fiscal policies in 1931 did best; those that abandoned the gold standard in 1933 did second best; France, which waited until the very end of the 1930s to start its New Deal, did worse.

Statisticians will tell you that if you thought before looking at this chart that it really did not matter what a New Deal did, that the pluses and the minuses of New Deal policies largely offset each other, that if you thought there was only 50–50 chance that New Deals mattered before looking at this chart, then after looking at this evidence you would be 95 percent sure that New Deals mattered.

Which part of the fiscal and monetary expansion of the New Deals in all the different countries mattered? Probably all of them. It is difficult to write down a model of the economy in which some tools work and others do not. All four of the aspects operate through boosting spending, either through boosting the money stock and hoping the velocity of money will remain unchanged, or through boosting the velocity of money and hoping that the money stock will remain unchanged. And any model of the economy in which increases in spending cause not just inflation but also boost employment and output will see that all four of these policy tools are likely to be effective.

Which of the four components of macroeconomic policy helped the most in the New Deal’s aiding of recovery? That is a much more difficult question. Christina Romer, who was here before, places enormous stress on the quantitative easing policies of the late 1930s, the mammoth expansions of the money supply even after in- terest rates on Treasury securities had already been reduced to ef- fectively zero, and says it played the most major role. Professor Galbraith earlier dissented from that.

Did the fiscal policy expansions help? Well, as Christina Romer said earlier, there were so little of them that it was hard to say. The gap between the size of the Great Depression in the United States and the magnitude of the extra-direct government spending was so large that it is truly hard to see whether fiscal policy might have mattered.

But as Professor Galbraith said, for evidence of the ability of fiscal policy to boost employment and production if used on a sufficiently large scale, we have to wait until World War II.

Monetary policy contraction, banking sector collapse, and the transformation of irrational exuberance into unwarranted pes- simism carried the U.S. unemployment rate up from 3 percent to 29 percent—or to 23 percent from 1929 to 1932. Monetary expan- sion, banking reform, and small deficits then drove the unemploy- ment rate down to 9.5 percent by the start of large-scale mobiliza- tion in 1940. And wartime government expenditures and deficits drove the unemployment rate down to 1.2 percent by 1944.

Thank you.

Senator BROWN. Thank you, Dr. DeLong.

I will sort of go left to right and ask each of you about 5 minutes’… Dr. DeLong, would you weigh in on the 1929–1939, 20 percent hours worked for adults, 20 percent lower? Do you think that is an accurate indicator of…

Mr. DELONG. It is a puzzling question that—and it is indeed the case that unemployment declined, the unemployment rate declined extremely sharply from 1932 to 1939, from 23 percent down to 11.3 percent, according to the Weir measure, and practically all of this is indeed an increase in the fraction of the labor force that has jobs and very little of it being a discouraged worker effect because that discouraged worker effect is not present, at least I at least can’t see it in David Weir’s Labor Force series.

But nevertheless, it is certainly true that hours of work per employed person were 13 percent lower in 1939 than in 1929, and Lee Ohanian wants to conclude that a substantial chunk of this decline is due to deficient demand, that the economy was getting better at sharing the available work hours among the workers but was not producing nearly as much demand for labor as we would want to see.

This is debatable. In 1949, hours worked per adult were 18 per- cent. In 1959, they were 17 percent below their 1929 level. But do we want to conclude that the economy was even more depressed in the 1950s than it was in 1939? No. The decline in hours worked tells us a lot about the cycle and the trend, that the decline in hours worked from 1914 to 1952 does not mean that the economy was performing much worse in 1952 than it was in 1914.

The Great Depression comes in the middle of the last sharp decline in the American work week we have seen, and shows us that Americans back then were deciding collectively to take a substantial part of their increased technological wealth and use it to buy increased leisure. And for that reason, I am more skeptical of the work hours comparison of 1939 to 1932 and 1929 and I tend to think that it makes more sense to take the unemployment rate as an indicator of how complete recovery is.

Senator BROWN. Interesting answer. Thank you.

What role did the Fed play in reversing the Great Depression? What policies, in particular, should it have pursued?

Mr. DELONG. Well, this is—I think when you, in fact, talk about the Federal Reserve and the Great Depression, there really are three questions. The first is did the Federal Reserve cause the Depression? Was the economy going along doing its normal thing and then the Federal Reserve all of a sudden decided to do something bad, and as a result we fell into the Great Depression? And I think the answer to that is clearly no, that the Great Depression started for other reasons. The Federal Reserve was simply a bystander, that, as Professor Galbraith said earlier, there are signs of substantial natural instability, right, in the economy, at least as it stood in the interwar period. Then it starts down and it keeps going down.

The second question is, could the Federal Reserve have interrupted the Great Depression? Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz’s Monetary History of the United States is a very large and very impressive book. I think Professor Galbraith calls it magisterial at some point in his written testimony. It argues the Federal Reserve could by itself have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks had it done enough to print up bank reserves, to encourage the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to print up currency, had it rescued threatened banks. But the Federal Reserve did not do so.

And this thesis of the Monetary History of the United States has, I think, taken profound damage over the last 2 years, for Chairman Bernanke of the Federal Reserve and his team have, via open market operations and now quantitative easing, they have done exactly what Friedman–Schwartz recommended and claimed would have stopped the Great Depression in its tracks. They have expanded bank reserves, the monetary base, and the money supply to an ex- tent I would not have believed possible 3 years ago. Yet we all think that this was not enough, that we need banking policy and probably fiscal policy, as well, in order to keep the Great Depres- sion currently the last depression that America has suffered.

I think this is a substantial intellectual loss for Friedman–Schwartz and an intellectual victory for Bernanke–Keynes, who argued that all the conventional interest rate and quantitative easing monetary policy in the world might not be enough if the capitalization of the banking sector vanished and the credit channel got itself well and truly clogged, which is where we seem to be.

The third question is what role did the Federal Reserve play in spurring recovery, and here we have the debate, and we have seen a piece of it in the debate between Chairman Romer and Professor Galbraith earlier, Christina Romer placing a very heavy weight on the quantitative easing policies of the Federal Reserve and of the gold inflow during the 1930s, arguing that even after the Federal Reserve has done everything it can to lower interest rates on Treasury securities to zero, if it continues to expand the money supply, well, that money burns a hole in people’s pockets and they spend it and that boosts spending, and Professor Galbraith placing more stress on what fiscal expansion there was and on the recovery of the banking system?

Here, well, my office and Professor Galbraith’s office is 1,000 miles away, but in her previous life, Christina Romer’s office is only 50 steps down the hall and she is very, very impressive and very convincing, so I tend to side with Christina on that one.

Senator BROWN. Fair enough…. The last word, Dr. DeLong.

Mr. DELONG. I think that the lesson from viewing fiscal anD monetary policy and government attempts to use them to serve as balance wheels of the economy since the Great Depression, of the abandonment of Herbert Hoover Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon’s dictum that liquidation is actually a healthy process, part of what economist Joseph Schumpeter called the natural breathing of the economic organism, that we have abandoned that and we think we have these policy tools and have been trying to use them and the question is how effective they are.

And I think the conclusion from 70 years of economists arguing and watching economies and watching the success of these tools is that almost all of the time monetary policy is more effective, and almost all of the time monetary policy is easier to implement and easier to change when conditions change, that it moves faster and it also is more flexible.

But then there come times like today, all right, times when the interest rate on safe short- and medium-term Treasury securities has been pushed all the way down to zero and in which you have to ask, if you undertake further expansionary monetary policy, well, whose incentives are you changing? We are economists. We believe that people respond to incentives, that government policies worked by changing the incentives that people face, but by the time you have pushed interest rates down to zero and can’t push them any further, whose incentives are you changing by continuing to rely on monetary policy?

And it is in that situation that we are now, and that is when you start dragging out the other tools of trying to keep spending in the economy at a normal pace. You know, the quantitative easing part of monetary policy, that maybe you can give people so much money it burns a hole in their pocket and they spend it, that the aggressive banking sector recapitalizations and government loan guarantee programs that we see the Treasury trying to roll out now that have their parallel in operations conducted by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation during the Great Depression, which had, if I may say so, an easier time. The RFC had powers to bring banks into conservatorship without declaring that they were insolvent.

And so to the extent that there is a fear that declaring that banks are, in the view of the government, insolvent will cause some kind of crisis of confidence and a shrinkage of the money stock as people pull their money out of banks, well, the RFC had tools that would avoid this, and perhaps Tim Geithner’s life would be a little bit easier at the Treasury if he had them now.

And last, there is the fiscal policy, that government spending, government tax cuts, with the idea that if the private sector is spending and is not staying stable, well, maybe the government can add to it and so keep things on an even keel. And I think the prudent thing is, when asked which of these should we be doing, is to say yes, all right, that when there is great uncertainty and when you have a number of tools for all of which there is some rea- son to believe they are at least somewhat effective, we will do what Roosevelt did, experimentation. Try them all and reinforce the ones that seem to be working.

8616 words

Senator BROWN. Thank you, Dr. DeLong.

Thank you all for joining us. This is the first of several hearings that will help Congress shape our response and our reaction to this economic crisis. I appreciate all of the service all of you have given by being here today and the good work you do, each in your institutions.

The record will be open for 7 days for Senator DeMint and the two other Members of the Subcommittee, and if you want to revise your remarks or add anything or respond to any of the questions that you didn’t feel that you got to respond to completely enough, certainly you are free to be in touch with the Subcommittee to do that, also.

The Committee is adjourned. Thank you very much. [Whereupon, at 4:34 p.m., the hearing was adjourned.]

(Remember: You can subscribe to this… weblog-like newsletter… here:

There’s a free email list. There’s a paid-subscription list with (at the moment, only a few) extras too.)

John Maynard Keynes (1938), ‘‘Private Letter to Franklin Delano Roosevelt of February 1’’ <http://tinyurl.com/dl20090325a>

John Maynard Keynes (1933), ‘‘Open Letter to Franklin Delano Roosevelt of December 31’’ <http://tinyurl.com/dl20090325b>.

Barry J. Eichengreen (1992), ‘‘The Origins and Nature of the Great Slump Revisited,’’ Economic History Review 45:2 (May), pp. 213–39.

See Christina D. Romer (1992), ‘‘What Ended the Great Depression?’’ Journal of Economic History 52:4 (December, pp. 757–784 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123226>