What Is the Current Macroeconomic Outlook Here in the U.S.?

What is the current macroeconomic outlook here in the United States?

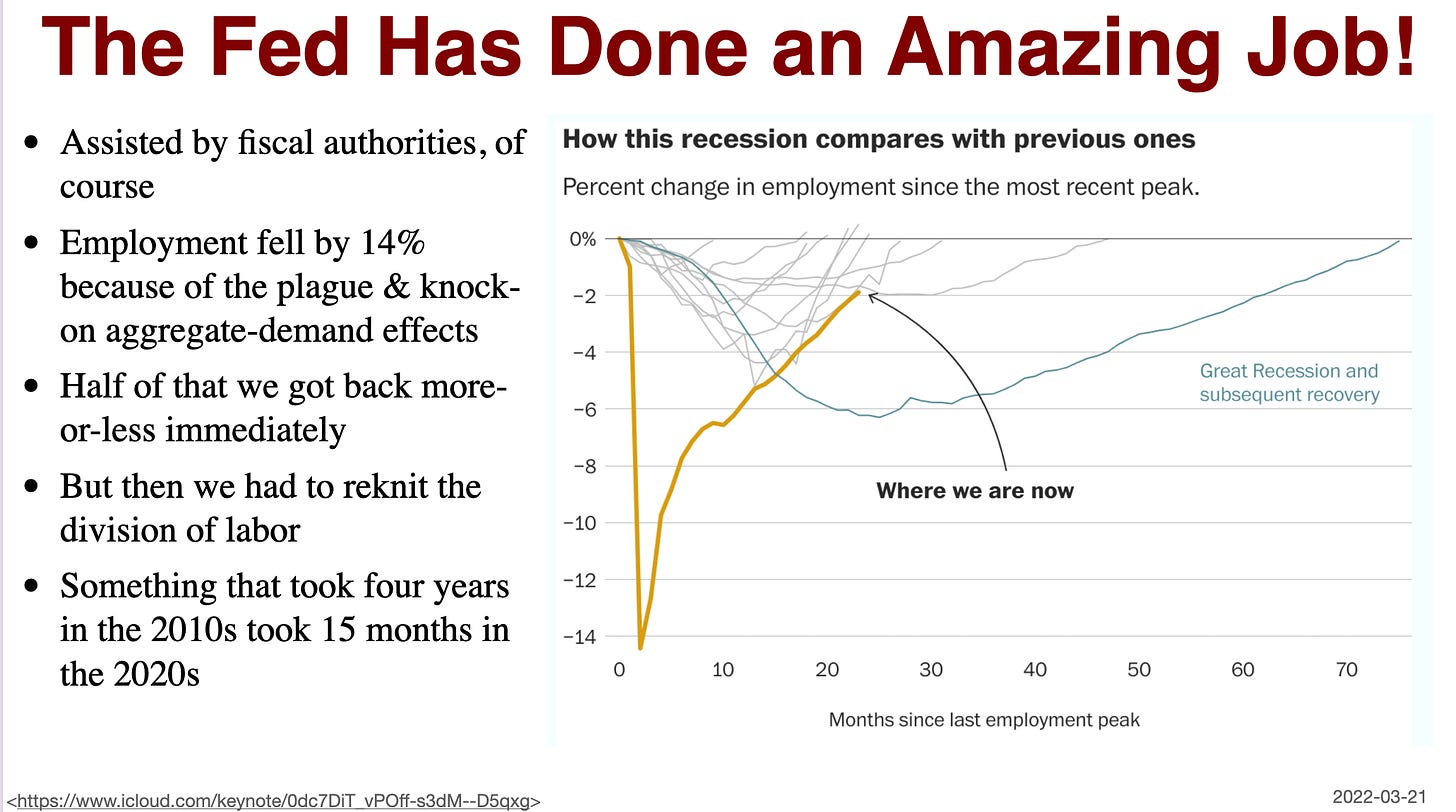

First of all, the Federal Reserve ought to be taking a good many victory laps. The coming of the plague bounced employment down by 14%, as pieces of the economy shut down to try to slow the spread and as only partially counterbalance the loss of income from those shut downs caused slack demand elsewhere in the economy. Then, with reopening, employment bounced up by 7%, leaving it about 7% below its pre-plague level.

Getting that 7% of employment back was going to be more difficult because the societal division of labor needed to be re-knitted in a new pattern. During the disappointing, anemic, unsatisfactory recovery from the great recession a decade ago, that re-knitting took place at a pace of only about 1.3 percentage points per year. With slack, inadequate, and only slowly growing demand, it was very difficult to figure out what business models would be profitable and where labor was really needed. But this time the economy has re-knit the division of labor to the amount of 5% of employment in a year because the Federal Reserve and the Biden administration did not, as their counterparts did in the early 2010s, take their feet off the gas pedal much too early.

This is a huge economic victory, perhaps the greatest in the United States I have seen. Jay Powell and Company should be rightly very proud.

But, as a side effect and a consequence, we have inflation. Our current inflation was inevitable, and is not regrettable: when you rapidly re-join the traffic at speed, you leave some of the rubber from your tires on the road. But what happens next?

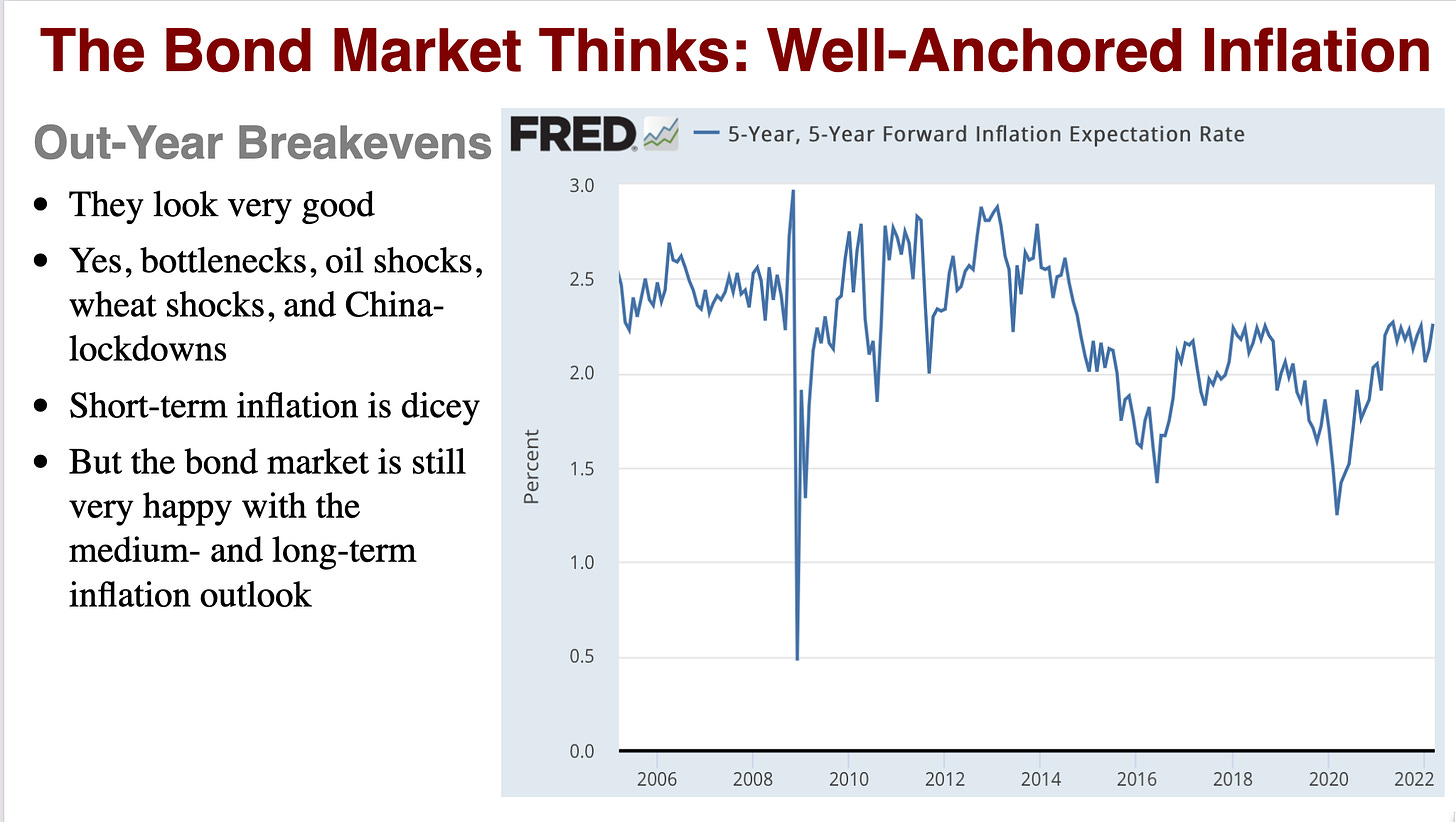

The bond market thinks that this wave of inflation will pass and things will return to normal not in the short but in the medium term. The bond market right now judges that between five and 10 years from now inflation will average 2.2% per year.

Is it right? Probably, but there is a chance that it is not.

I believe that the bond market’s judgments are relatively trustworthy here. They are, however, to be trusted not because the bond market is a good forecaster. The bond market is not. But if our current inflation does not die away quickly, it will be because people do not expect it to die away quickly. And, as Joe Gagnon of the PIIE points out, the people whose expectations matter for this substantially overlap with the people placing bets on the bond market.

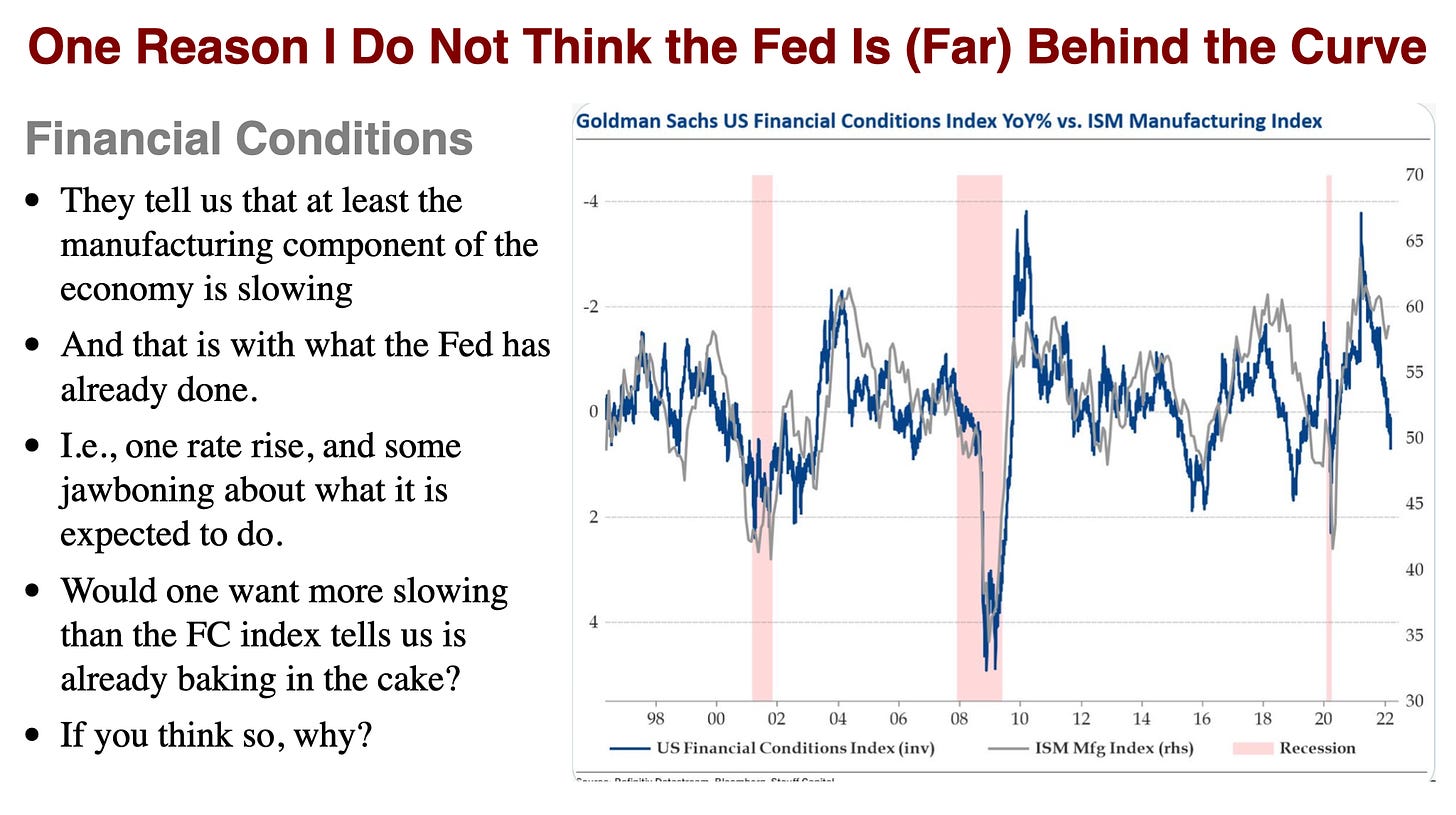

In addition, Goldman Sachs reports that its US Financial Conditions index is softening rapidly, and the FCI has been a good guide in the past to the strength of the business cycle. Thus there seems to be less worry about "overheating" of the economy in the next year and a half than one might have feared.

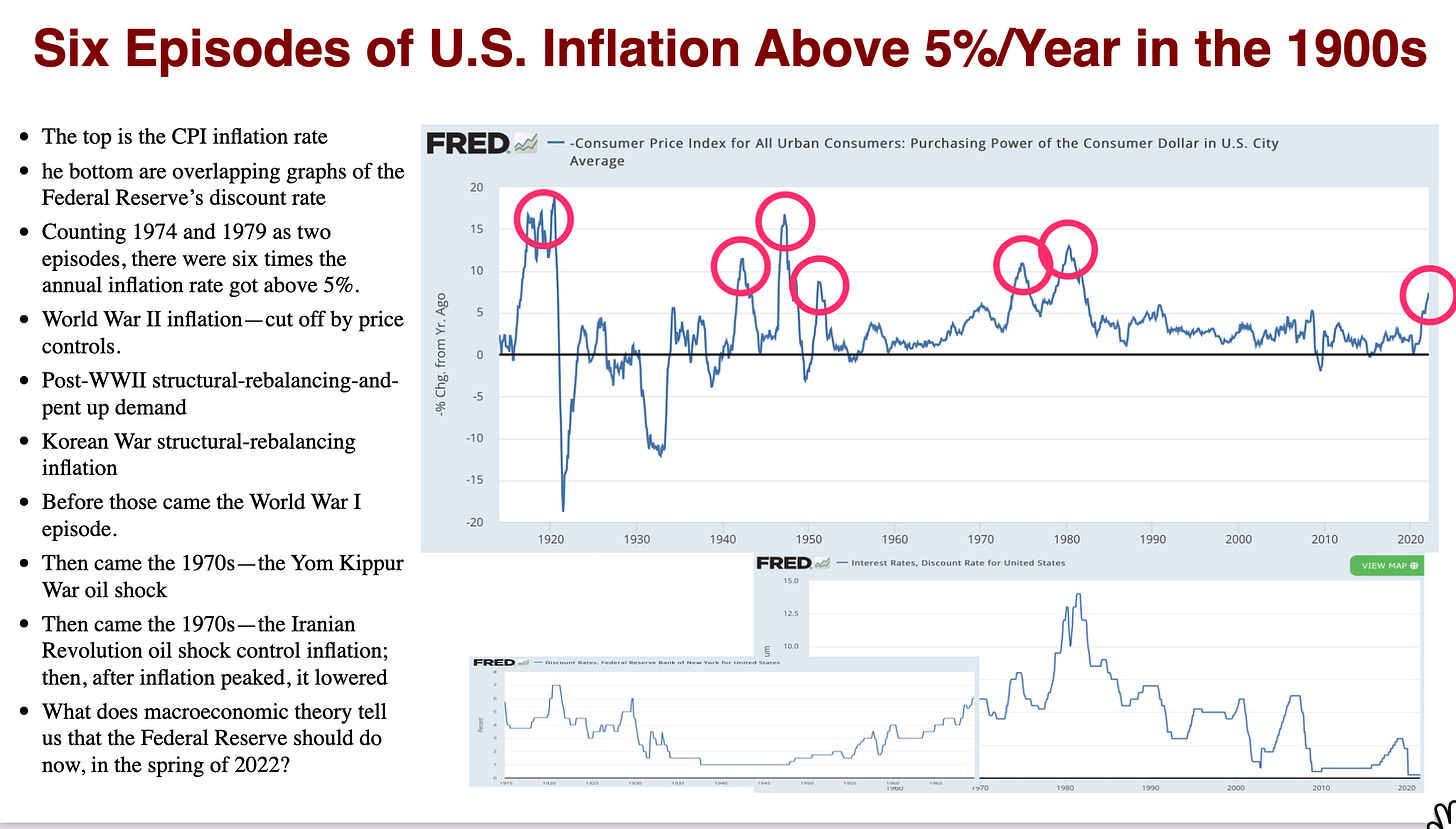

Stepping back, there were six episodes of US inflation above 5% in the 1900s. One, the World War II inflation, was cut off by price controls. One, the World War I inflation, was cut off and turned into substantial deflation and a deep but short recession by what Milton Friedman judged had been an excessive increase by the Federal Reserve and interest rates from 3.75 to 7%. Two, the post World War II and the Korean War inflations, were transitory and passed quickly without substantial monetary tightening. And two made up the 1970s inflation, ultimately scotched only by the deep recession of the Volcker disinflation.

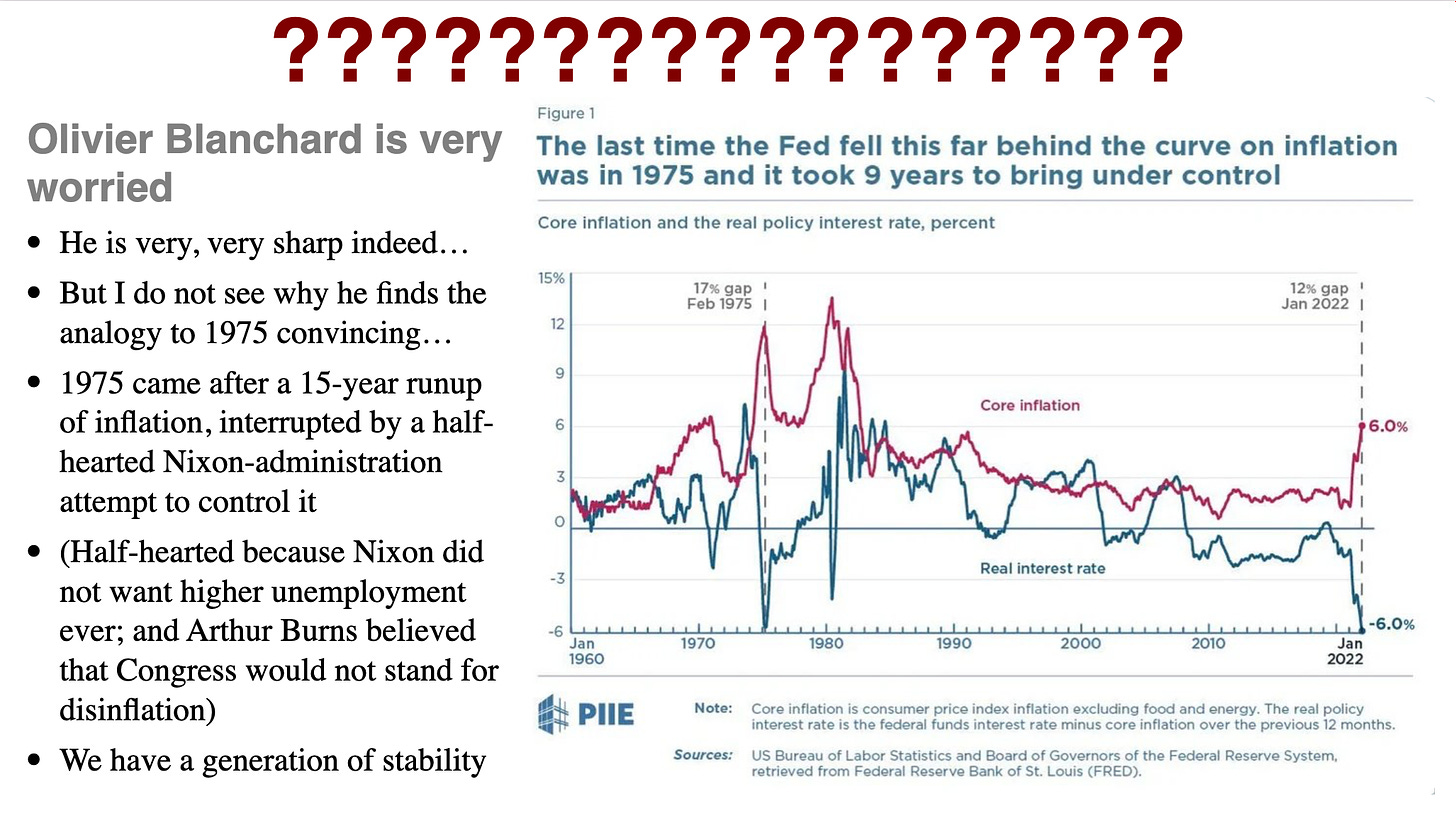

Everybody making arguments about the likely course of inflation right now is, whether they recognize it or not, basing their arguments not on theoretical principles but on a judgment of which historical episode is the best analogy. Those who, like my extremely sharp teacher Olivier Blanchard, see the 1970s as the best analogy may be correct, but they have a very weak case: the 1974 outbreak of inflation came after a previous inflation wave that had shifted expectations. By 1973 people expected that inflation would, in the absence of ongoing recession, be about what inflation had been last year—and, if anything, a little more. I see exactly zero evidence for this loss of the anchoring of inflation expectations.

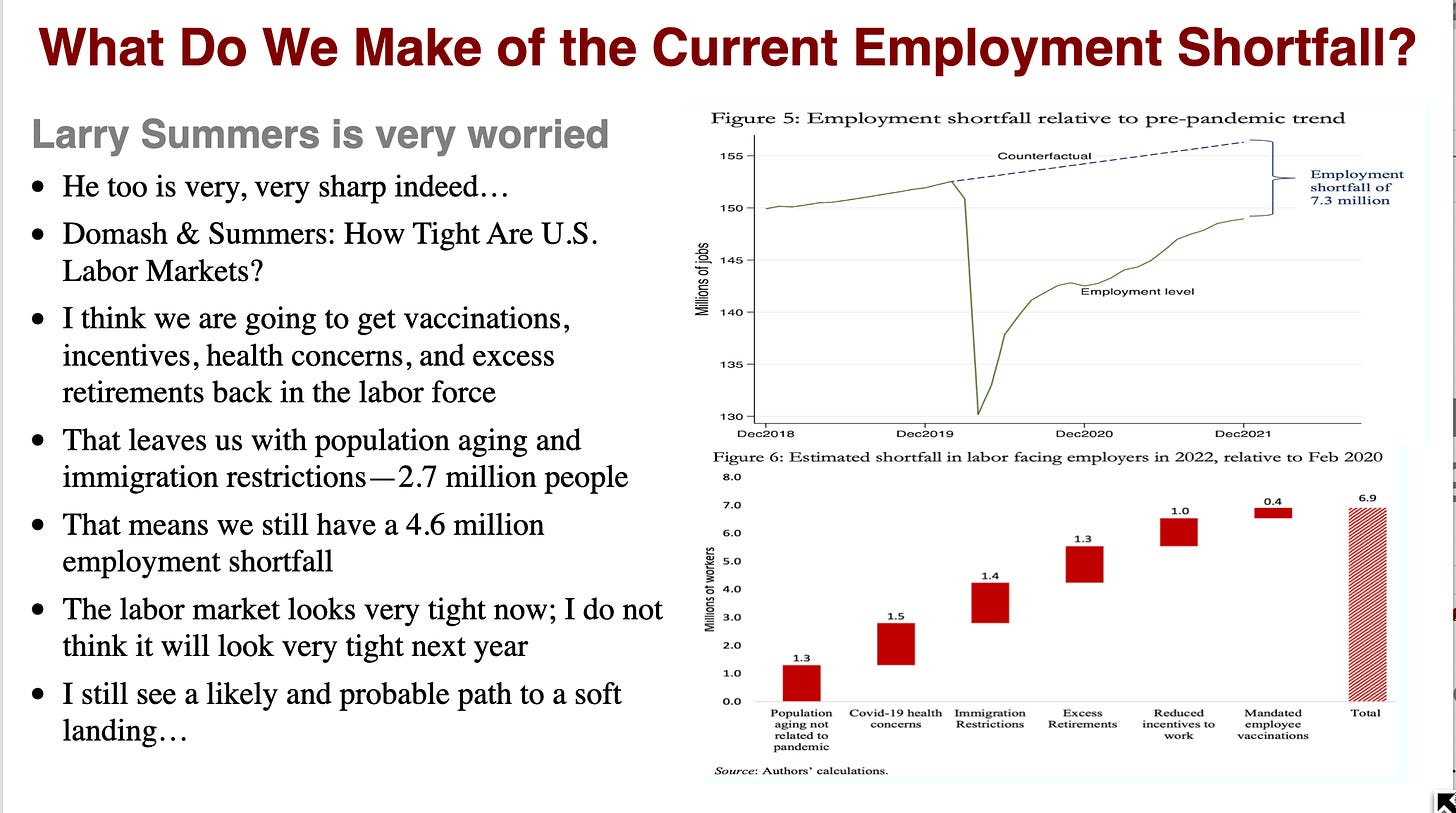

Employment is still some 7.3 million below its pre-plague trend. My extremely sharp teacher Larry Summers and Alex Domash see 2.7 million of those as due to structural factors—population aging and immigration restrictions—that cannot be reversed. But that still leaves 4.6 million that are now out of the labor force but could be possibly tempted back in by a sufficiently strong economy of high opportunity. That potential pool makes me fear an inflationary wage spiral less.

An inflationary spiral as employers try to hire more workers than can ever be available, supply-chain bottlenecks, and self-fulfilling expectations—of the three possible sources of a non-transitory inflation, only an inability to resolve supply-chain bottlenecks seems to me at least to be a potentially serious risk. And here comes the bad news: Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s attack on the Ukraine has, as happened in the early 1970s, sent prices of oil and grain spiraling upward. There is some chance the 1970s will turn out to be the right analogy after all.

I'm surprised lack of convenient, affordable childcare didn't make the employment shortfall graph.