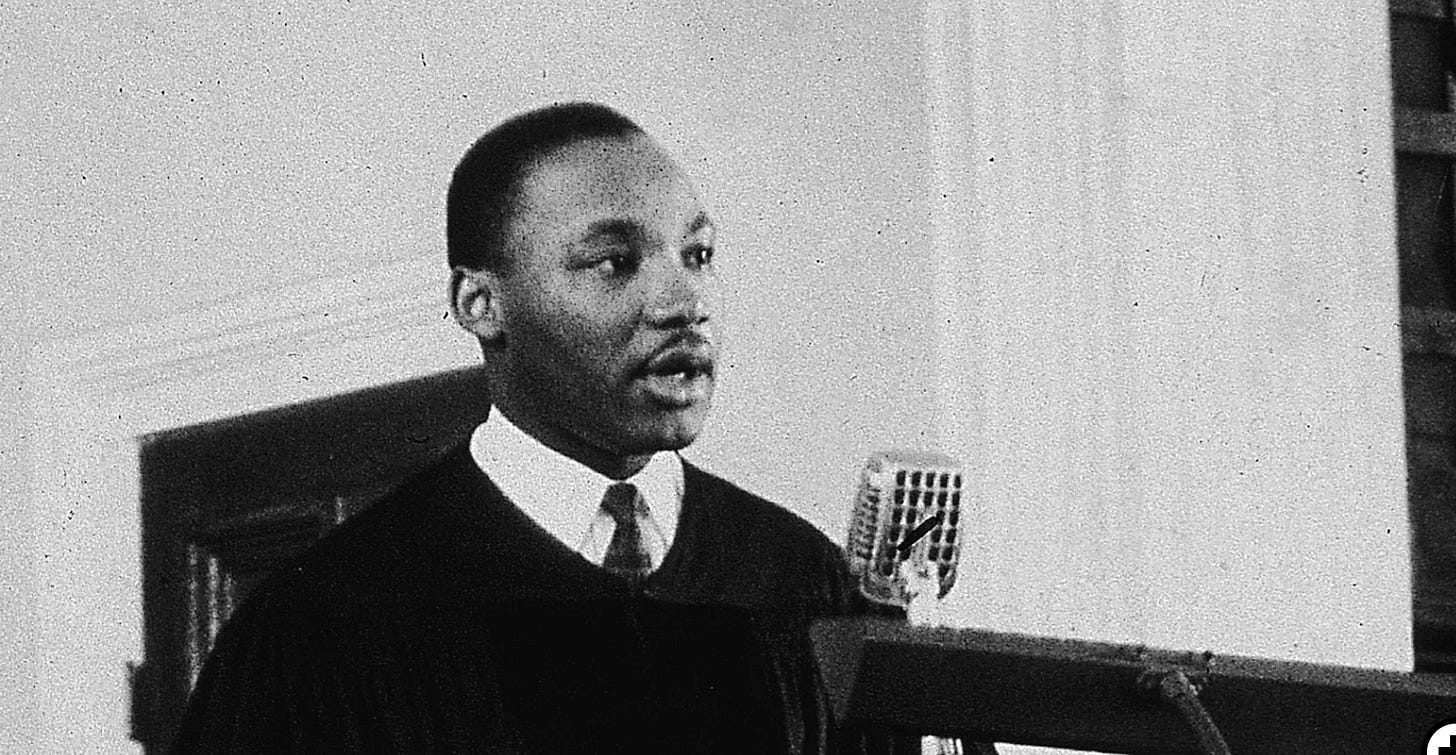

READING: Martin Luther King, Jr. (1958): Out of the Long Night

“The nonviolent resistor… knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. There is a creative power in the universe that works to bring low gigantic mountains of evil and pull...

“The nonviolent resistor… knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. There is a creative power in the universe that works to bring low gigantic mountains of evil and pull down prodigious hilltops of injustice…. God is on the side of truth and justice. Good Friday may occupy the throne for a day, but ultimately it must give way to the triumph of Easter…. Yes, ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’…”

We can all certainly agree that the arc of the moral universe is long. But does it bend toward justice? Or do the wicked flourish like the green bay tree in this fallen sublunary sphere, corrupted as it is by Ialdobaoth and the archons? Camus would say that it does not matter, or that it should not matter, or that the fact that we have not yet killed ourselves shows that it does not matter for us. It is fitting and proper to roll the boulder up Mount Nebo…

IN AMERICAN life there is today a real crisis in race relations. This crisis has been precipitated, on the one hand, by the determined resistance of reactionary elements in the South to the Supreme Court's momentous decision against segregation in the public schools. Many states have risen in open defiance. Legislative halls of the South ring loud with such words as interposition and nullification. The Ku Klux Klan is on the march again, determined to preserve segregation at any cost. Then there are the White Citizens Councils. All of these forces have conjoined to make for massi^'e resistance.

The crisis has been precipitated, on the other hand, by the radical change in the Negro's evaluation of himself. There would probably be no crisis in race relations if the Negro continued to think of himself in inferior terms and patiently accepted injustice and exploitation. But it is at this very point that the change has come. For many years the Negro tacitly accepted segregation. He was the victim of stagnant passivity and deadening complacency. The system of slavery and segregation caused many Negroes to feel that perhaps they were inferior. This is the ultimate tragedy of segregation. It not only harms one physically, but it injures one spiritually. It scars the soul and distorts the personality. It inflicts the segregator with a false sense of superiority while inflicting the segregated with a false sense of inferiority.

But through the forces of history something happened to the Negro. He came to feel that he was somebody. He came to feel that the important thing about a man is not the color of his skin or the texture of his hair, but the texture and quality of his soul. With this new sense of dignity and new self respect a new Negro emerged. So there has been a revolutionary change in the Negro's evaluation of his nature and destiny, and a determination to achieve freedom and human dignity.

This determination springs from the same deep longing for freedom that motivates oppressed people all over the world. The deep rumblings of discontent from Asia and Africa are at bottom a quest for freedom and human dignity on the part of people who have long been the victims of colonialism and imperialism. The struggle for freedom on the part of oppressed people in general and the American Negro in particular is not suddenly going to disappear. It is sociologically true that privileged classes rarely ever give up their privileges without strong resistance. It is also sociologically true that once oppressed people rise up against their oppression there is no stopping point short of full freedom. So realism impels us to admit that the struggle will continue until freedom is a reality for all of the oppressed peoples of the world.

Since the struggle will continue, the basic question which confronts the oppressed peoples of the world is this: How will the struggle against the forces of injustice be waged?

There are two possible answers. One is to resort to the all too prevalent method of physical violence and corroding hatred. Violence, nevertheless, solves no social problem; it merely creates new and more complicated ones. Occasionally violence is temporarily successful, but never permanently so. It often brings temporary victory, but never permanent peace. If the American Negro and other victims of oppression succumb to the temptation of using violence in the struggle for justice, unborn generations will be the recipients of a long and desolate night of bitterness, and their chief legacy to the future will be an endless reign of meaningless chaos.

The alternative to violence is the method of nonviolent resistance. This method is nothing more and nothing less than Christianity in action. It seems to me to be the Christian way of life in solving problems of human relations. This method was made famous in our generation by Mohandas K. Gandhi, who used it to free his country from the domination of the British Empire. This method has also been used in Montgomery, Alabama, under the leadership of the ministers of all denominations, to free 50,000 Negroes from the long night of bus segregation. Several basic things can be said about nonviolence as a method in bringing about better racial conditions.

First, this is not a method of cowardice or stagnant passivity; it does resist. The nonviolence resistor is just as opposed to the evil against which he is protesting as the person who uses violence. It is true that this method is passive or nonaggressive in the sense that the nonviolent resistor is not aggressive physically toward his opponent, but his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade the opponent that he is mistaken. This method is passive physically, but it is strongly active spiritually; it is nonaggressive physically, but dynamically aggressive spiritually.

A second basic fact about this method is that it does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding. The nonviolent resistor must often voice his protest through nonco-operation or boycotts, but he realizes that nonco-operation and boycotts are not ends within themselves; they are means to awaken a sense of moral shame within the opponent. The end is redemption and reconciliation. The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness.

A third fact that characterizes the method of nonviolence is that the attack is directed to forces of evil, rather than to persons caught in the forces. It is evil that we are seeking to defeat, not the persons victimized with evil. Those of us who struggle against racial injustice must come to see that the basic tension is not between races. As I like to say to the people in Montgomery, Alabama, "The tension in this city is not between white people and Negro people. The tension is at bottom between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. And if there is a victory it will be a victory, not merely for 50,000 Negroes, but a victory for justice and the forces of light. We are out to defeat injustice and not white persons who may happen to be unjust."

A fourth point that must be brought out concerning the method of nonviolence is that this method not only avoids external physical violence, but also internal violence of spirit. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love. In struggling for human dignity the oppressed people of the world must not succumb to the temptation of becoming bitter or indulging in hate campaigns. To retaliate with hate and bitterness would do nothing but intensify the existence of hate in our world.

We have learned through the grim realities of life and history that hate and violence solve nothing. They only serve to push us deeper and deeper into the mire. Violence begets violence; hate begets hate; and toughness begets a greater toughness. It is all a descending spiral, and the end is destruction—for everybody. Along the way of life, someone must have enough sense and morality to cut off the chain of hate by projecting the ethic of love into the center of our lives.

In speaking of love, we are not referring to some sentimental and affectionate emotion. It would be nonsense to urge men to love their oppressors in an affectionate sense. Love in this connection means understanding goodwill as expressed in the Greek word agape. This means nothing sentimental or basically affectionate; it means understanding, redeeming goodwill for all men, an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return. It is spontaneous, unmotivated, groundless, and creative. It is the love of God operating in the human heart. When we rise to love on the agape level, we rise to the position of loving the person who does the evil deed, while hating the deed that the person does.

A fifth basic fact about the method of nonviolent resistance is that it is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice. It is this deep faith in the future that causes the nonviolent resistor to accept suffering without retaliation. He knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. There is a creative power in the universe that works to bring low gigantic mountains of evil and pull down prodigious hilltops of injustice. This is the faith that keeps the nonviolent resistor going through all of the tension and suffering that he must inevitably confront.

Those of us who call the name of Jesus Christ find something at the center of our faith which forever reminds us that God is on the side of truth and justice. Good Friday may occupy the throne for a day, but ultimately it must give way to the triumph of Easter. Evil may so shape events that Caesar will occupy a palace and Christ a cross, but that same Christ arose and split history into A.D. and B.C., so that even the life of Caesar must be dated by his name. Yes, "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice." There is something in the universe which justifies William Cullen Bryant in saying, "Truth crushed to earth will rise again." So in Montgomery, Alabama, we can walk and never get weary, because we know that there will be a great camp meeting in the promised land of freedom and justice.

I cannot close this article without saying that the problem of race is indeed America's greatest moral dilemma. The churches are called upon to recognize the urgent necessity of taking a forthright stand on this crucial issue. If we are to remain true to the gospel of Jesus Christ, we cannot rest until segregation and discrimination are banished from every area of American life.

Many churches have already taken a stand. The National Council of Churches has condemned segregation over and over again, and has requested its constituent denominations to do likewise. Most of the major denominations have endorsed that action. Many individual ministers, even in the South, have stood up with dauntless courage. High tribute and appreciation is due the ninety ministers of Atlanta, Georgia, who so courageously signed the noble statement calling for compliance with the law and a reopening of the channels of communication between the races. All of these things are admirable and deserve our highest praise.

But we must admit that these courageous stands from the church are still far too few. The sublime statements of the major denominations on the question of human relations move too slowly to the local churches in actual practice. Too many ministers are still silent.

It may well be that the greatest tragedy of this period of social transition is not the glaring noisiness of the so-called bad people, but the appalling silence of the so-called good people. It may be that our generation will have to repent not only for the diabolical actions and vitriolic words of the children of darkness, but also for the crippling fears and tragic apathy of the children of light.

What we need is a restless determination to make the ideal of brotherhood a reality in this nation and all over the world. There are certain technical words which tend to become stereotypes and cliches after a certain period of time. Psychologists have a word which is probably used more frequently than any other word in modem psychology. It is the word maladjusted. In a sense all of us jmust live the well adjusted life in order to avoid neurotic and schizophrenic personalities.

But there are some things in our social system to which all of us ought to be maladjusted. I never intend to adjust myself to the viciousness of mob-rule. I never intend to adjust myself to the evils of segregation and I the crippling effects of discrimination. I never intend to adjust myself to the inequalities of an economic system which I takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes. I never intend to become adjusted to the madness of militarism and the self-defeating method of physical violence.

It may be that the salvation of the world lies in the hands I of the maladjusted. The challenge to us is to be maladjusted—as maladjusted as the prophet Amos, who in the midst of the injustices of his day, could cry out in words that echo across the centuries, "Let judgment run down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream"; as maladjusted as Lincoln, who had the vision to see that this nation could not survive half slave and half free; as maladjusted as Jefferson, who in the midst of an age amazingly adjusted to slavery could cry out in words lifted to cosmic proportions, "All men are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness"; as maladjusted as Jesus who could say to the men and women of his generation, "Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them that despitefully use you." The world is in desperate need of such maladjustment. Through such courageous maladjustment we will be able to emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man's inhumanity to man into the bright and glittering daybreak of freedom and justice.

References:

Camus, Albert. 1942. Le Mythe de Sisyphe. Paris: Gallimard. <https://archive.org/details/mythofsisyphus0000camu_h4b8>.

King, Martin Luther, Jr. 1958. “Out of the Long Night”. Gospel Messenger 107:6 (February 8), p. 3 ff. <https://archive.org/details/gospelmessengerv107mors/page/n178/mode/1up>.

If reading this gets you Value Above Replacement, then become a free subscriber to this newsletter. And forward it! And if your VAR from this newsletter is in the three digits or more each year, please become a paid subscriber! I am trying to make you readers—and myself—smarter. Please tell me if I succeed, or how I fail…

MLK was operating under some pretty important unstated assumptions in calling for nonviolent resistance. That's a tactic that can only succeed in specific circumstances which he failed to specify. It never would have worked against, say, Stalin. It worked for Ghandi against the British because other nations could pressure them; because there could be, and was, democratic resistance to the British government; and because the British were never willing to use Stalinist brutality even against people they considered inferior.

The same essential conditions worked in favor of King in the US, with the added boost from the existence of Northern states unwilling to support the brutality of Southern racists and a federal government with, at long last, power to intervene.

It's unfortunate that there aren't any universal remedies for tyranny, but each case calls for different strategies and tactics.

Also noticed: https://prisonculture.substack.com/p/coretta-scott-king-and-looking-backwards