Matt Klein Has a Very Nice Review & Critique of Slouching Towards Utopia

& so I, once again, go **blush**… The book and I have many friends...

CONDITION: Somewhat Annoyed at þe “Generative AI” Hype:

When the very sharp Derek Thompson writes:

Derek Thomson: AI Is Coming for the Thought Leaders: ‘This year, we’ve seen a flurry of AI products that seem to do precisely what the Oxford researchers considered nearly impossible: mimic creativity…. GPT-3…. DALL-E 2…. Midjourney…. I’ve been experimenting with various generative AI apps and programs…. For years, I’ve imagined a kind of disembodied brain that could give me plain-language answers to research-based questions. Not links… or lists…. A tool… already in development… Consensus…. Type a research question in the search bar… and the app combs through millions of papers and spits out the one-sentence conclusion from the most highly cited sources…. Consensus is part of a constellation of generative AI start-ups that promise to automate… reading, writing, summarizing, drawing, painting, image editing, audio editing, music writing, video-game designing, blueprinting, and more…. Using AI to learn how experts work, so that the AI could perform the same work with greater speed. I came away from our conversation fixated on the idea that AI can master certain cognitive tasks by surveilling workers to mimic their taste, style, and output…. So that’s what I’ve been doing with my career, I thought. Mindlessly constructing a training facility for someone else’s machine…. When the Vox reporter Kelsey Piper asked GPT-3 to pretend to be an AI bent on taking over humanity, she found that “it played the villainous role with aplomb”…

I say: Wait a minute! That’s not right! Noah Smith and Roon are right!”:

Noah Smith & Roon: Generative AI: autocomplete for everything: ‘No one knows, of course, but we suspect that AI is far more likely to complement and empower human workers than to impoverish them or displace them onto the welfare rolls…. Instead of replacing people entirely… technologies simply replaced some of the tasks they did…. As Noah likes to say, “Dystopia is when robots take half your jobs. Utopia is when robots take half your job.”…

The current wave of generative AI does things very differently from humans…. Because of these differences, we think that the work that generative AI does will basically be “autocomplete for everything”. The most profoundly impactful generative AI application to come out thus far is a tool aptly called GitHub Copilot…. Copilot is able to suggest the next few lines of code for a programmer based upon what he or she has already written…. Before a software engineer had to remember, search for, or infer all low level functionalities…. They can now describe in plain language what they would like a snippet of their program to do, and if it’s within the capacity of the language model, synthesize it from nothing!… Noah imagines that at some point, his workflow will look like this: First, he’ll think about what he wants to say, and type out a list of bullet points. His AI word processor will then turn each of these bullet points into a sentence or paragraph, written in a facsimile of Noah’s traditional writing style. Noah will then go back and edit…. Many artists will likely have a similar workflow…. The “sandwich” workflow…. A human has a creative impulse, and gives the AI a prompt. The AI then generates a menu of options. The human then chooses an option, edits it, and adds any touches they like.…Just as some modern sculptors use machine tools, and some modern artists use 3d rendering software, we think that some of the creators of the future will learn to see generative AI as just another tool—something that enhances creativity by freeing up human beings to think about different aspects of the creation...

For a long, long time into the future—perhaps forever—computers will be much better at generating options than at filtering and assessing them. Creativeity is not just generating alternatives, but figuring out which of them is the best—is what the author wanted, but did not initially know it.

FOCUS: A Very Nice Review & Critique of Slouching Towards Utopia:

A very nice review and critique of Slouching Towards Utopia <bit.ly/3pP3Krk> from the highly estimable Matt Klein:

Some highlights:

Matt Klein: "Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century": ‘I really liked this line (366): "There is no a priori reason to think that the economic organization best suited to inventing the industrial future should be the same as the one best suited to catching up to a known target…"

And:

Matt Klein: "Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century": Brad Delong's new history makes an important point well, and gave me a lot of food for thought…. [It] is an argument for recognizing how the world since 1870... above all is characterized by unprecedentedly rapid change... radically different than the world before 1870....

And:

Matt Klein: "Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century": The central paradox, for Delong, is that the growth in humanity’s productive potential since 1870 should have been sufficient to create something like a “utopia” for everyone by now, at least by the standards of anyone alive in 1870…

And:

Matt Klein: "Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century": Yet despite the dramatic progress our species has experienced, we remain far from that ideal.... Our desires have grown to match our capabilities.... The gains... have not been distributed particularly evenly...

Here let me interrupt the flow of praise: My thumbnail description—which Bob Reich suggested to me—is that, while we have made extraordinary progress at figuring out how to bake a sufficiently large economic pie so that, potentially, everyone can have enough, the problems of slicing and tasting that economic pie have completely flummoxed us. Thus while we are rich and powerful beyond the wildest dreams of avarice of previous centuries, that is all. We can neither equitably distribute our wealth nor properly utilize it to live wisely and well, so that people feel safe and secure, and live lives in which they are healthy and happy. To say “have not been distributed particularly evenly” and “our desires have grown” catches only half of it. Distribution has not been inept, but has been positively poisonous. And utilization has fallen vastly short not just because of our rising expectations: people 200 years ago would also have hoped along with us for a world in which they were not stalked by flying killer robots, and in which sinister people in steel and glass towers did not attempt to hypnotize them via dopamine loops to glue their eyes to screens in terror so they could be sold fake diabetes cures and crypto grifts.

Overall, I am of course very flattered by Matt’s high praise.

One of the greatest things about publishing this book is figuring out how many good-hearted friends willing to give attention and thought the book has turned out to have—and that I have turned out to have, for the book is me in a very real sense.

However, as I asked of Matt, then there is the “BUT!”:

Matt Klein: "Slouching Towards Utopia" and "The Long 20th Century": ‘But I have some quibbles:

[1] There is surprisingly little discussion of either industrial research labs or corporations. With remarkably few exceptions, we get almost no insight into how the post-1870 growth engine actually worked…

[2] Delong… identifies… Joseph Schumpeter, Karl Popper, Peter Drucker, Michael Polanyi, Karl Polanyi, and Friedrich Hayek. (They stand in contrast to violent fantasists such as Hitler, Lenin, Mao, and Mussolini.)... Constrained by space, Delong decided to focus only on Hayek and Karl Polanyi…. That fits well with Delong’s focus on the conflicts over how to distribute the gains of the post-1870 windfall, but I think it ended up detracting from some of his other arguments...

[3] The paucity of material about Canada, Europe, and Japan, especially after WWII, is unfortunate.... In general, I wish there were a lot more about Japan...

[4] I would have expected the chapter on WWII to highlight the Allies’ material advantages and describe how the war was won thanks to superior industrial organization and scientific prowess... the Manhattan Project, Bletchley Park.... I also would have expected the ideas that Adam Tooze laid out so masterfully in The Wages of Destruction and The Deluge would have played a larger role in Delong’s narrative of the 1920s-1940s. Germany was technologically underdeveloped and resource-poor...

[5] I wish the section on the Marshall Plan had mentioned the importance of the U.S. using currency aid to force the rest of western Europe—particularly France—to accept the reality that West Germany needed to reindustrialize and become economically integrated with its neighbors…

[6] Speaking of which: there is almost no discussion of financial history and financial innovation in Slouching, except at the very end in the context of 2008…

[7] There was no mention of the provisional government in Russia that followed the February revolution...

[8] My other major criticism (I have a few narrower ones that I will mention lower down) is that I am not convinced that the “long 20th century” actually ended…. [Perhaps] the agonizingly slow growth in the years after the global financial crisis represents a fundamental break in the trend towards ever-rising prosperity. But that is a claim one could have made just as well in the 1930s—and it would have turned out to have been wrong…. While I am willing to believe that the “long 20th century” may have ended when Delong says it did—on the grounds that global growth has been much weaker than in the past—I have little reason to believe that this sad state of affairs must persist..

[9] Climate change is a serious problem that had not received the attention it deserves until recently, but there is little reason to think that it is a serious impediment to the growth trajectory humanity has experienced since 1870....

[10] The section on the 1920s and the Great Depression gave too much credence to the Friedman-Schwartz view that the problem was tight monetary policy from the Federal Reserve, in my view. I would have preferred more of a discussion of the Eccles/Keynes/Kindleberger view that the problem was excessive debt, the imbalanced income distribution, and the decisions by the Bank of France and the Fed to sterilize gold inflows...

[11] Delong has a throwaway comment that the slowdown in productivity growth (as opposed to total growth) since 1970 could be explained in part by the fact that “energy diverted away from producing more and into producing cleaner would quickly show up in lower wage increases and profits” (431). I’m not sure I buy this but I would have appreciated more of an explanation either way...

[12] Finally, I would have liked more on this (453): “It is normal for a plutocratic elite, once formed, to use its political power to shape the economy to its own advantages. And it is normal for this to put a drag on economic growth. Rapid growth like that which occurred between 1945 and 1973, after all, requires creative destruction; and, because it is the plutocrats’ wealth that is being destroyed, they are unlikely to encourage it.” A different version of the book would have used this to frame a long discussion of antitrust and public choice theory. More generally, I would love to know the extent to which the post-1870 boom was due to the suppression of this “normal” behavior. If so, what caused that? And how can we restore the dynamism and competition that Schumpeter recognized was so essential for progress?…

To [1] and [2} I plead guilty, and throw myself on the mercy of the court. In my mind’s eye, the book I would write written in letters of fire that directly inscribed their truth on the brain of the reader and so was a treasure for all time started from the claim that 1870 was the true hinge of history, and then went in three directions:

Backward from 1870 earlier in time to trace how it came about the 1870 was the hinge Dash and how, previously, there was no alternative hinge.

Forward from 1870 later in time to trace how the research lab-, corporation-, and global market economy-enabled discovery, development, deployment, and diffusion of technologies, 80 repeated, unprecedented, revolutionary, Schumpeterian creative-destruction pace worked itself it leading sector by leading sector and trailing sector by trailing sector.

Forward from 1870 later in time to trace the political-economy consequences for human society of this unprecedented advance toward technology revolution-driven material cornucopia.

Will MacAskill’s What We Owe the Future book from Basic is 352 pages. Jacob Soll’s Free Market: The History of Ideas book from Basic is 336 pages. My book is 624 pages. I will not say that the memory of hearing my publisher scream in tears still rings in my ears. But I will say that asking Basic to sell a book this long in its usual excellent way is asking it to do a heavy lift, and taking it will out of its comfort zone.

In addition to the 624 pages published, there are another 400 odd pages on the cutting room floor, and there are notes, quotations, bullet points, and outlines for a further 500 pages. Maybe I could have delivered on my original plan if I had published the book in three volumes from a university press, but I really wanted Basic’s excellent marketing machine on my side. Probably I could not have delivered the larger opus: the difficulty of the project goes with the square of the length.

So I am really sorry that I could not deliver, and that as a result of my failure Matt justly makes his criticisms [1] and [2].

(Parenthetically, I suspect Will MacAskill faced the same problem with his What We Owe the Future—too much to say, and it not being clear how to say it. His book reads to me like five 60-page book prospectuses, each of which could have been 300 pages, stapled together. Not, I hasten to say, that it is not a very very good book: it is.)

I think Matt’s criticisms [3] through [7] are also valid. There should be more about Canada, Europe, and Japan, for while the U.S. was “the furnace where the future was being forged” my probably excessive focus on it as in some sense the leading point-guard of humanity’s slouch towards utopia harmed the book. A greater share of my points could and should have been made by drawing examples from elsewhere in the global north rather than falling-back on the U.S. examples with which I am most comfortable. Yes, Adam Tooze’s The Deluge and Wages of Destruction are magnificent accomplishments, so magnificent that I greatly envy the author, and I think it was the anxiety-of-influence (plus their existence) that kept a great deal of my 1920-1945 chapters from being simply regurgitated precises of Tooze’s artguments. (But, while Germany was resource-poor, I do think he overstates the extent to which it was technologically underdeveloped for its day.) More on how the U.S. imposed the mixed economy on western Europe after WWII and more on global finance as the nervous system of the globalized market economy would have improved the book. And, yes, Kerensky, Wladimir Woytinsky, and their gallant company of the democratic forces in Russia deserved a spotlight.

When it comes to Matt’s criticisms [8] through [10], however, I do want to push back: I really think that the Grand Narrative of the Long 20th Century is success at baking and failure at slicing and tasting a sufficiently large econoic pie, and that while we do not know what the Grand Narrative of the era that started sometime after 2000 will be, it will be something different. I do see fossil-fuel emissions-generated global warming as a huge challenge not so much because of technocratic and geoengineering concerns but because of political economy concerns—and I note, in support of that belief, that Matt Klein cannot bring himself to say “global warming”, let along “fossil-fuel emissions-generated global warming”. As for the causes of the Great Depression, I see the Bank of France and the Federal Reserve as mediator-causes in the Friedman-Schwartz story, and debt as an accelerant of an ongoing process rather than as a spark.

And Matt’s [11] and [12] are not so much critiques, as calls for separate extra essays. Maybe I will write them. :-)

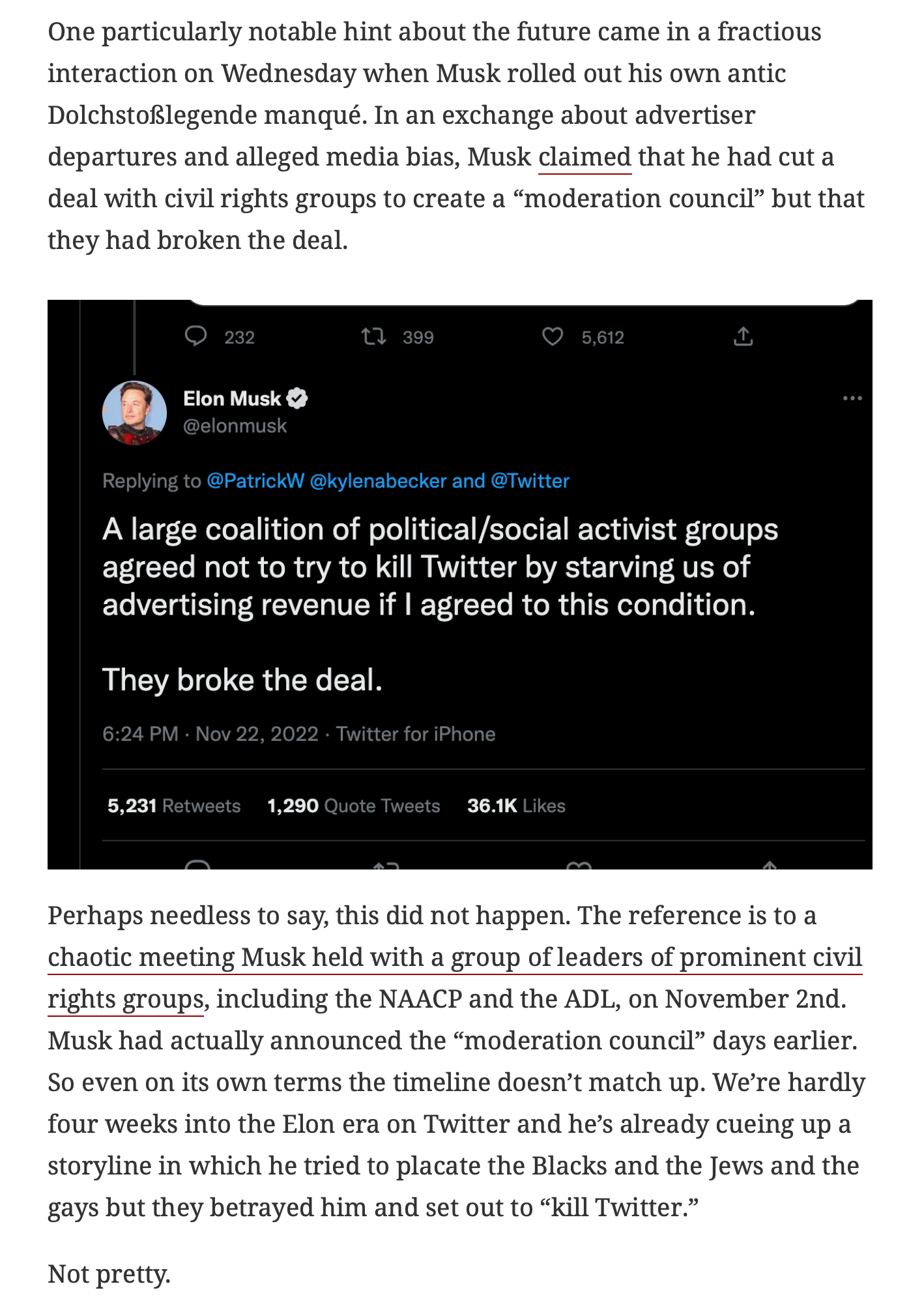

One Image: Elon Musk Goes Full Conspiracy Theory on Us:

Josh Marshall has the receipt:

I do not see Musk’s tenure as Twitter paranoid chaos monkey going well at all.

From my perspective as a corporate lawyer (ret.), I can easily imagine how the kind of AI described could work in drafting of M&A agreements, registration statements and the like. Many firms, including mine, are already using document assembly software to do some of this, although, to this point, it doesn’t approach the sort of AI capabilities described.

There has been resistance even to this much. I knew late Silent Generation/early Boomer partners who, as recently as ten or fifteen years ago, were still having their secretaries print out their new emails every morning, and then, having read them in hard copy, dictating their responses for the secretary to type up and send out.

Partly this kind of thing is just innate guild conservatism, but there are also professional responsibility issues. How good does the AI need to be so that choosing a reasonable AI package and asking it reasonably adequate questions is a defense to a malpractice claim if the AI makes a mistake or commits some other infelicity that the human in the loop doesn’t catch? Do you have to tell clients that you are using AI? What if a client prefers that you do things the old fashioned way?

The dumb AI that litigators are already using for “electronic discovery” raises similar issues. If you’re using software to do the first review of millions of documents, and the software misses something important, is that your fault? You can’t very well have the program review a million documents and then also review them yourself, just to be sure. You can establish quality control sampling protocols, but then the adequacy, or not, of your protocol can become an issue.

It is little understood outside my particular area of practice, but the availability of public databases, particularly the SEC’s EDGAR platform, that put all the material agreements of every public company and, more importantly, every material agreement that the opposing law firm has drafted for any of its public company clients, online, revolutionized the practice of corporate, M&A and securities law over the last twenty-five years.

Before EDGAR became mandatory for public companies in the mid-90s, every corporate negotiation was bespoke, because it was virtually impossible to find specimen agreements, outside of your own firm’s archives. We fought out agreements draft by draft on the basis of first principles--“we should do it our way because [reasons]”--and negotiating skill. Now, and for at least the last twenty years, negotiations are almost entirely about what is “market” for the particular term or condition under consideration. Opposing counsel knows exactly what you have previously agreed to on that point for your current client, and all your clients, and the entire universe of public company agreements can be accessed an analyzed to determine what people usually do in this situation, which is what is “market.”

It dramatically narrows the scope, tenor and timeline of negotiations. It’s also less fun for the lawyers, which is of course beside the point.

AI - translation software has been like this for some years (and like everything in this vein can be expected to improve steadily). Having the base document in a machine translation saves a good deal of tedium but leaves quite a lot of the more interesting bit still to be done. But I've used it to prepare published documents, where the final stage is to query an expert fluent in the language and knowledgeable about the subject matter, on one or two interesting points.

Some of what is described is just more machine translation - from English to English, or from English to a program language, or from generic English to our own English.

For some purposes the machine translation is perfectly adequate - notably for online reading in general where one may want to go back and check a really botched phrase, or one may not care.

I believe translator's rates per word have gone down since machine translation came in (quite some time ago). What this means for their income is less clear. But the utopia of having half your job done by a computer is more likely to become a shareholders' utopia.