CONDITION: HELP!

Charlie Stross: ’2016: Brexit, Trump, voted in. My reactions: 2017: We need to be invaded by the Culture. 2018: I’ll settle for the Daleks. 2019: Moon Nazis? Anyone?…

First: Monetary & Fiscal Policy in a Low-Interest Rate Economy

Paul Krugman has some interesting musings on these issues: Paul Krugman: Credible Irresponsibility Revisited <https://stonecenter.gc.cuny.edu/credible-irresponsibility-revisited/>. And Olivier Blanchard: Fiscal Policy Under Low Interest Rates <https://fiscal-policy-under-low-interest-rates.pubpub.org/>…

Let’s rewind the tape:

Ever since the late 1820s, When John Stuart Mill was writing Essays on Some Unsettled Questions in Political Economy, it has been at least moderately clear that the task of a central bank in normal times is to adjust the money supply to money demand, so as to make Say’s Law true in the practice even though it is false in theory—to avoid either the general glut that is the flipside of an excess demand for or the inflationary inability to purchase at expected prices that is the flipside of an excess supply of money.

In the neo-Wicksellian language that was re-introduced to economic-policy debates in the mid-1990s by Alan Greenspan, this requires the central bank to match the market real interest rate r to the “neutral“ real interest rate r*. But what if the market nominal rate is at the zero lower bound, yet the real rate is still above the neutral rate? As Paul Krugman wrote last week:

An economy that remains depressed even at zero interest rates ‘wants’ expected inflation. With flexible prices it will get there by deflating now so that it can inflate later. But why put [a sticky-price economy] through that wringer? Far better… to give… the inflation without the deflation, by promising that the central bank will do whatever it takes to assure… inflation… high enough to get r down to r*.”

That is what a central bank will do if it is following the rule of trying to make Say’s Law true in practice. That is how it can get prices and incentives as close as possible to those in a flex-price well-functioning macroeconomy, given the stickinesses of wages, prices, and debt contracts that we have. And so that inflation is not a disturbance of the optimal macroeconomic market allocation, but rather an instantiation of it.

Yet, Krugman notes, nobody has listened to him. Instead of talking about how when the central bank hits the zero lower bound it should then generate the inflation that an optimal flex-price economy would deliver, “instead… the discussion is about… deficit spending…. Why? One reason is “the dead hand of conventional wisdom.” But, Paul Krugman says, there are “real arguments for keeping the inflation target low if you can still achieve full employment.” (I would stress that if.)

What are those real arguments? I see two: (1) a stable unit-of-account yardstick is genuinely useful for contracting purposes, and (2) conserving on cognitive resources is helpful for behavioral reasons.

But does this mean one should definitely resort to fiscal policy instead? It is not obvious. The way the argument usually goes, using expansionary fiscal policy instead of expected inflation to unwedge an economy with high unemployment stuck at the zero lower bound has huge dangers and drawbacks on its own. It leads to excessive debt accumulation which requires high entrepreneurship-destroying taxes to amortize. It crowds out productive private investment as well. It is thus a two-fold drag on long-run economic growth. Plus there is the risk of cracking the government’s status as a provider of safe assets, with resulting risks of financial crisis and national bankruptcy.

But, Larry Summers and I argued back in 2012, this argument via appeal to excessive fear of public debt is simply incoherent when the economy is at its zero lower bound, for in a low interest-rate economy the difficulties of financing the national debt—and thus whatever drag on growth is generated by debt accumulation—are not increased but rather decreased by successful expansionary debt-financed fiscal policy. And how about the drag from the crowding-out of private investment? As Paul wrote:

When interest rates… are below the economy’s growth rate… the economy shouldn’t accumulate [more] capital…. [With] a distinction between the interest rate on… a safe asset, and… higher rates of return on private investment… the appropriate r in the r-g comparison is somewhere between [safe and risky]…. What matters is… the rate of return on those forms of investment that would be stimulated by negative real interest rates…. Cho[osing] to pursue higher public spending at the expense of lower private investment… mainly… substituting government expenditure for residential investment…

And, I would add, substituting government expenditure for dissipative grifts—for low interest rates induce organizations that are not well-setup to judge risks to take risks in reaching for yield, and one of the oldest tricks in the financial book is to make money by inducing your counterparty to take on risks that they do not understand.

As I see it, the question of which r—a risk-free safe asset or a risky one, and, if risky, how risky—should be compared to the economy’s growth rate g is a subtle one, and it hinges on where in the economy the risk premium comes from. In our economies, the financial-asset risk premium does not come from risk aversion induced by a declining marginal utility of wealth: it is simply ludicrous to pretend that it is so or, if it is so, it is because of an astonishing failure to mobilize society’s true risk-bearing capacity that must be due to other, major financial market failures. What are they?

It has always seemed to me that the presumption is that risk-bearing and investment-judging capacity does not combine with capital in fixed proportions, and that a world with less investment is one in which investment projects use more of risk-bearing and investment-judging resources. Thus my belief is that the right r to use in the g>r comparison has to be very very close to the risk-free rate.

What about when things change, and when you exit the g>r régime? It has always seemed to me that the costs and risks of such are low—governments, after all, have enormous powers of financial regulation to ultimately boost demand for their debt, if they wish, providing that the government can tax enough to keep the debt position fundamentally sound in the long run.

But these are “active research issues”.

References:

Paul Krugman: Credible Irresponsibility Revisited <https://stonecenter.gc.cuny.edu/credible-irresponsibility-revisited/>

Olivier Blanchard: Fiscal Policy Under Low Interest Rates <https://fiscal-policy-under-low-interest-rates.pubpub.org/>

Olivier Blanchard: Public Debt and Low Interest Rates <https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/wp19-4.pdf>

Paul Krugman: It’s Baaack: Japan's Slump & the Return of the Liquidity Trap <https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/1998/06/1998b_bpea_krugman_dominquez_rogoff.pdf>

Paul Krugman: It’s Baaack: 20 Years Later <https://m.gc.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/2021-07/Its-baaack.pdf>

Peter Temin & Barry Wigmore: The Gold Standard & the Great Depression <https://www.jstor.org/stable/20081742>

Barry Eichengreen: Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard & the Great Depression <https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/0195101138.001.0001/acprof-9780195101133>

David Reifschneider & John C. Williams: Three Lessons for Monetary Policy in a Low Inflation Era <https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/1999/199944/199944pap.pdf>

Peter A. Diamond: National Debt in a Neoclassical Growth Model <https://www.jstor.org/stable/1809231>

Philippe Weil: Overlapping Generations: the First Jubilee <https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01022015/document>

One Audio: The Persistence of Neoliberalism:

Kai Wright & Corey Robin: Why the ‘Reagan Regime’ Endures <https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/anxiety/episodes/reagan-regime>

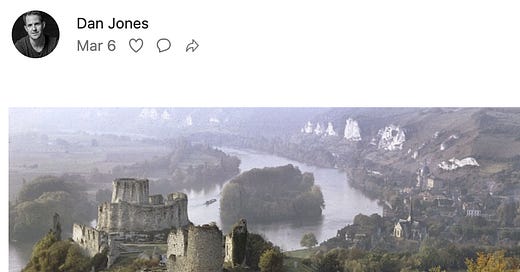

One Picture: Château Gaillard:

Very Briefly Noted:

Trent Telenko: ’This is a quick thread on Russian plans, maps, and trucks.🧵 We are going to start with Ukraine & explain…

Elizabeth Spiers: Do Journalists Need to Be Brands?: ‘Trick question. You already are one, whether you want to be or not… <https://espiers.medium.com/do-journalist-need-to-be-brands-5e0510dfa67b>

Dylan Matthews: How War Became a Crime: ‘Putin is violating a surprisingly powerful international law, and other nations are punishing him accordingly… <https://www.vox.com/22959938/crime-war-kellogg-briand-ukraine-conquest>

Martin Wolf: There Are No Good Choices for the west on Ukraine: ‘It should strengthen sanctions, though they may ruin Russia’s economy without changing its policy or regime… <https://www.ft.com/content/6ec8777e-e6b3-4be6-9e64-8cfaf71d1e18>

Ben Thompson: Apple’s Silicon Event, Scaling the M Series, UltraFusion & Integration<https://stratechery.com/2022/apples-silicon-event-scaling-the-m-series-ultrafusion-and-integration/>

Ethan Wu: Oil Shocks Need Not Stoke Inflation: ‘A crucial component of the 1970s inflationary spiral was labour’s ability to secure wage increases at the tempo of inflation… <https://www.ft.com/content/f6db5ef9-789b-4eac-9cf3-d81b29ac0ebc>

Ryan Avent: Globalization Is Not a Politically Antiseptic Process: ‘The difficulty Russia has had… may mean that Russia’s capacity to engage in other territorial adventures is considerably diminished, and that a Chinese attempt to take Taiwan by force is now much less likely…

Pushkar: The Apple-TSMC Partnership: ‘The advanced node, high volume, and quick ramp products like Apple iPhone SoCs were critical in helping TSMC debug and stabilize yields on the most complex, advanced geometry process nodes… Without the massive volumes from Apple, it is unlikely that TSMC would have been able to catch up…

Paragraphs:

Thomas Piketty: A Brief History of Equality: ‘A short but sweeping and surprisingly optimistic history of human progress toward equality despite crises, disasters, and backsliding. A perfect introduction to the ideas developed in his monumental earlier books…. Piketty guides us with elegance and concision through the great movements that have made the modern world for better and worse: the growth of capitalism, revolutions, imperialism, slavery, wars, and the building of the welfare state. It’s a history of violence and social struggle, punctuated by regression and disaster. But through it all, Piketty shows, human societies have moved fitfully toward a more just distribution of income and assets, a reduction of racial and gender inequalities, and greater access to health care, education, and the rights of citizenship. Our rough march forward is political and ideological, an endless fight against injustice. To keep moving, Piketty argues, we need to learn and commit to what works, to institutional, legal, social, fiscal, and educational systems that can make equality a lasting reality…

LINK: <https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674273559>

Martin Wolf: Rishi Sunak Owes Britain More than Warmed-Over Thatcherism: ‘Politicians with Thatcherite leanings need to dig deeper to understand why performance has been so mediocre. Many of them emphasise the need for a “lower tax economy”, Sunak among them. But the evidence suggests this is quite unimportant, however much the self-interested wealthy insist upon the opposite. According to the IMF, among these 15 countries, the UK’s tax burden is third from the lowest. If high taxes crippled prosperity, the UK should be among the richest. It is not. Finland, Belgium, Austria, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and Norway all have substantially higher tax burdens and higher GDP per head. So, when Sunak states that “I firmly believe in lower taxes”, he is just uttering ideology. That ideology has costs. The UK’s distribution of household disposable income is much the most unequal of these 15 countries, according to the OECD. Moreover, this was also the result of the shifts in the 1980s, which have never been reversed. In assessing the record, one also cannot ignore the financial crisis and subsequent austerity, both of which were outcomes of the Thatcherite ideology…

LINK: <https://www.ft.com/content/7bc81120-d4c6-4fba-9faf-60380461267b>

Andrew Gelman: Interview: ‘For an empirical research paper to be good… it should just add to our understanding of the world…. For example, consider this abstract from “The Curse of Good Intentions: Why Anticorruption Messaging Can Encourage Bribery,” by Nic Cheeseman and Caryn Pfeiffer: “Anticorruption awareness-raising efforts may be backfiring… nudging… to “go with the corrupt grain.”… A household-level field experiment… in Lagos… to test whether exposure to five different messages about (anti)corruption influence the outcome of a “bribery game.” We find that exposure to anticorruption messages largely fails to discourage the decision to bribe…. The effect of anticorruption messaging is conditioned by an individual’s preexisting perceptions regarding the prevalence of corruption.” I like this abstract: It argues for the relevance of the work without making implausible claims. Maybe part of this is that their message is essentially negative…

LINK:

"I would add, substituting government expenditure for dissipative grifts—for low interest rates induce organizations that are not well-setup to judge risks to take risks in reaching for yield, and one of the oldest tricks in the financial book is to make money by inducing your counterparty to take on risks that they do not understand."

My bank noticed that my savings portfolio is not 100% equities. Naturally, the fixed-income component has a very low yield. So they called me up to pitch something that they portrayed as a high-yielding note. I looked at the structure, and it was just a bunch of options - a strip of autocallables wrapped up in a knockout barrier. Limited upside and 100% downside risk, the opposite of most notes with embedded options pitched to retail investors.

I was too lazy to try to price the structure (and I do this for a living), but since the terms were fixed in advance, it follows that it could not have been at-market and must have been not only just a bunch of options, but just a bunch of options *at rippoff prices*.

Re: Monetary & Fiscal Policy in a Low-Interest Rate Economy:

Seems like a problem is in reframing policy as "what interest rate." The Fed should just stick to it's mandate of stable prices (=2% PCR inflation) and maximum employment and interest rates are whatever they have to be to carry out that policy. Of course that puts the uncertainty on "maximum employment" but that's surely closer to being observable than r*.

And whatever the Fed's instrument, there is no role for "fiscal policy" unless the Fed is self constrained in its willingness to purchase private vs public debt (as it seemed to be in the QE days).